RIDGEVIEW: a COLLECTION of SHORT STORIES a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrolling Fall 2008 75 Th Ranger Regiment Association, Inc

PATROLLING FALL 2008 75 TH RANGER REGIMENT ASSOCIATION, INC. VOLUME 23 ISSUE II Vietnamese Rangers (37 th Biet Dong Quan), and their US advisors inspect a captured NVA recoilless rifle during the battle at Khe Sanh, Tet, 1968. Trench lines were necessary due to sniper fire and constant incoming enemy rounds. Senior Advisor CPT Walter Gunn is in the forefront, Officers’ Messages ................................1-10 kneeling; SFC Willard Langdon, 4 th from right, with BDQ General ..................................11-24 & 72-80 patch. Unit Reports ........................................25-71 CHINA - BURMA - INDIA VIETNAM IRAN GRENADA PANAMA IRAQ SOMALIA AFGHANISTAN PATROLLING – FALL 2008 PATROLLING – FALL 2008 WHO WE ARE: The 75th Ranger Regiment Association, Inc., is a We have funded trips for families to visit their wounded sons and registered 501 (c) corporation, registered in the State of Georgia. We were husbands while they were in the hospital. We have purchased a learning founded in 1986 by a group of veterans of F/58, (LRP) and L/75 (Ranger). program soft ware for the son of one young Ranger who had a brain The first meeting was held on June 7, 1986, at Ft. Campbell, KY. tumor removed. The Army took care of the surgery, but no means existed OUR MISSION: to purchase the learning program. We fund the purchase of several awards 1. To identify and offer membership to all eligible 75th Infantry Rangers, for graduates of RIP and Ranger School. We have contributed to each of and members of the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol the three Battalion’s Memorial Funds and Ranger Balls, Companies, Long Range Patrol Companies, Ranger and to the Airborne Memorial at Ft. -

This Letter Was Written by Bernard Leo Tonry Sr. of NY. Born in Drumfin, County, Sligo, Ireland at the 12 Mile House on the Old Boyle to Sligo Road, and Died in NY

1 This letter was written by Bernard Leo Tonry Sr. of NY. Born in Drumfin, County, Sligo, Ireland at the 12 mile house on the old Boyle to Sligo Road, and died in NY. (12/04/1908 - 05/28/1993) Typed by his daughter Eileen Tonry in 1977. retyped by John James Tonry 02/2000 to this format Sent to me by Ruthann (Tonry) Roberts of Tulsa,Ok. A cousin. Hand written above typing "This to you I dedicate in your quest-for history of your family. (?) May you find some information from (?) it. I don't think (2 more words not readable) Really old Ben." Note (?) means I guessed I have 50/50 chance of being right or wrong. JJT Started this Columbus Day October 10,1997 To begin with,as a sort of introduction to what may follow, maybe a thousand times , I have through of leaving behind me a simple account of my life as I remember it. Someday some of my grandchildren may get enjoyment out of my Jottings. For me or anyone else to try and remember and put into detail all that has happened since early childhood to the present creates a challenge to a failing sense of memory. To my children and grandchildren I dedicate this crude but true account of all that I can possibly remember of this long distant account of years gone by. This story if you may call it of my past up to present is being told by the writer, Grandpa Tonry, better known as Ben, the second youngest of twin boys in a family of eleven, leaving a sister younger than I. -

Blarney-Stone-April-2021-Specials

April 2021 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 Family Special: 16” 2- Country Fried Chicken Beer Battered Fish & Family Special; 16” 2- Topping Pizza, Lg. sand. w/fries or chips Fried Shrimp w/ fries or Topping Pizza, Lg. House Salad,2 sm. Pasta of the Week Garlic Shrimp Fettucini chips House Salad, 2 sm. Appetizers: $27.99 Appetizers: $27.99 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Family Special: 16” 2- Chicken Modiga sand. Patty Melt w/Fries or Chipotle BBQ Chicken Tijuana Roast beef sand Hot Pepper Chicken Family Special: 16” 2- Topping Pizza, Lg. w/fries or chips Chips sand. w/ Fries or Chips w/ fries or chips Club sand. w/Fries or Topping Pizza, Lg. House Salad,2 sm. Chips House Salad, 2 sm. Appetizers: $27.99 Pasta of the Week Beef Tortellini Appetizers: $27.99 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Family Special: 16” 2- Frisco Melt Burger Chicken Club Wrap Turkey Rueben sand. Portabella Mushroom Hot Three Meat Sub Family Special: 16” 2- Topping Pizza, Lg. w/fries or chips w/Fries or Chips w/fries or chips Burger w/Fries or Chips sand. w/fries or chips Topping Pizza, Lg. House Salad, 2 sm. House Salad, 2 sm. Appetizers: :$27.99 Pasta of the Week Chicken Broccoli Alfredo Appetizers: $27.99 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Family Special: 16” 2- Ciabatta Chicken Club Steak Modiga Wrap w/ Meatball sand. w/Fries Family Special: 16” 2- Topping Pizza, Lg. Cajun Chicken Caeser Brunch Burger w/Fries or sand. -

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

On Faith-Healing New Secular Humanist Centers?

New Secular More on Humanist Faith-Healing Centers? James Randi Paul Kurtz Gerald Larue Vern Bullough Henry Gordon Bob Wisne David Alexander Faith-healer Robert Roberts Also: Is Goldilocks Dangerous? • Pornography • The Supreme Court • Southern Baptists • Protestantism, Catholicism, and Unbelief in France 1n Its Tree _I FALL 1986, VOL. 6, NO. 4 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 17 BIBLICAL SCORECARD 62 CLASSIFIED 12 ON THE BARRICADES 60 IN THE NAME OF GOD 6 EDITORIALS Is Goldilocks Dangerous? Paul Kurtz / Pornography, Censorship, and Freedom, Paul Kurtz I Reagan's Judiciary, Ronald A. Lindsay / Is Secularism Neutral? Richard J. Burke / Southern Baptists Betray Heritage, Robert S. Alley / The Holy-Rolling of America, Frank Johnson 14 HUMANIST CENTERS New Secular Humanist Centers, Paul Kurtz / The Need for Friendship Centers, Vern L. Bullough / Toward New Humanist Organizations, Bob Wisne THE EVIDENCE AGAINST REINCARNATION 18 Are Past-Life Regressions Evidence for Reincarnation? Melvin Harris 24 The Case Against Reincarnation (Part 1) Paul Edwards BELIEF AND UNBELIEF WORLDWIDE 35 Protestantism, Catholicism, and Unbelief in Present-Day France Jean Boussinesq MORE ON FAITH-HEALING 46 CS ER's Investigation Gerald A. Larue 46 An Answer to Peter Popoff James Randi 48 Popoff's TV Empire Declines .. David Alexander 49 Richard Roberts's Healing Crusade Henry Gordon IS SECULAR HUMANISM A RELIGION? 52 A Response to My Critics Paul Beattie 53 Diminishing Returns Joseph Fletcher 54 On Definition-Mongering Paul Kurtz BOOKS 55 The Other World of Shirley MacLaine Ring Lardner, Jr. 57 Saintly Starvation Bonnie Bullough VIEWPOINTS 58 Papal Pronouncements Delos B. McKown 59 Yahweh: A Morally Retarded God William Harwood Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Doris Doyle, Steven L. -

The Effects of Superstition As Destination Attractiveness on Behavioral Intention

The Effects of Superstition as Destination Attractiveness on Behavioral Intention Yunzhou Zhang Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Hospitality and Tourism Management Muzaffer Uysal, Committee Chair Ken McCleary Vincent P. Magnini May 2, 2012 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: destination attractiveness, superstition attitude, behavioral intention, superstition as destination attractiveness (SADA) The Effects of Superstition as Destination Attractiveness on Behavioral Intention Yunzhou Zhang ABSTRACT Superstitious beliefs date back thousands of years and continue to the present, and research suggests that superstitious beliefs have a robust influence on product satisfaction and decision making under risk. The study therefore examines how superstition attitude will impact potential tourists’ intention to visit a destination so that relevant organizations (e.g. destination management/marketing organizations) could better understand potential tourists’ behaviors, identify a niche market encompassing those prone to superstition, and tailor the tourism products to the needs and beliefs of potential tourists. The study used a survey instrument which consists of four components: the scale of Superstition as Destination Attractiveness (SADA), the revised Paranormal Belief Scale, the measurement of Intention to Visit, and respondents’ demographics and travel experiences. A mixed-method data collection procedure was adopted -

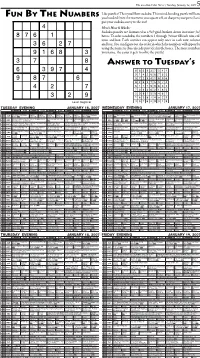

Answer to Tuesday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, January 16, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING JANUARY 16, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING JANUARY 17, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone CSI: Miami: Wannabe Dog the Dog the Dog the Dog the Dog the Dog the CSI: Miami: Wannabe CSI: Miami: Legal (TV14) The Sopranos (TVMA) The Sopranos: Meadowlands Tony Dog Bounty CSI: Miami: Legal (TV14) 36 47 A&E (TV14) (HD) Hunter (R) Hunter (R) Hunter (R) Hunter (R) Hunter (R) Hunter (R) (TV14) (HD) 36 47 A&E (HD) (HD) checks out Dr. Melfi. (TVMA) (HD) (TVPG) (HD) America’s Funniest Home Videos: No Business in Boston Legal: Nuts (N) KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live According According Knights Emergency Primetime: Medical Mys- KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live 4 6 ABC Show Business (TVPG) (N) (HD) at 10 (N) (TV14) (N) 4 6 ABC Jim (HD) Jim (HD) Prosp. -

People, Objects, and Anxiety in Thirties British Fiction Emily O'keefe Loyola University Chicago

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The Things That Remain: People, Objects, and Anxiety in Thirties British Fiction Emily O'Keefe Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Emily, "The Things That Remain: People, Objects, and Anxiety in Thirties British Fiction" (2012). Dissertations. Paper 374. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/374 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2012 Emily O'keefe LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE THINGS THAT REMAIN: PEOPLE, OBJECTS, AND ANXIETY IN THIRTIES BRITISH FICTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY EMILY O‘KEEFE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2012 Copyright by Emily O‘Keefe, 2012 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Joyce Wexler, who initially inspired me to look beyond symbolism to find new ways of engaging with material things in texts. Her perceptive readings of several versions of these chapters guided and encouraged me. To Pamela Caughie, who urged me to consider new and fascinating questions about theory and periodization along the way, and who was always ready to offer practical guidance. To David Chinitz, whose thorough and detailed comments helped me to find just the right words to frame my argument. -

The Politics of Autism

The Politics of Autism The Politics of Autism Bryna Siegel, PhD 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Siegel, Bryna, author. Title: The politics of autism / by Bryna Siegel. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017053462 | ISBN 9780199360994 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Autism—Epidemiology—Government policy—United States. | Autism—Diagnosis—United States. | Autistic people—Education—United States. Classification: LCC RC553.A88 S536 2018 | DDC 362.196/8588200973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017053462 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America For David CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction xi 1. -

II. Comprehension:8Pts A

First Term - Exam 1 Full Name: _____________________________ Class: _____________ Time: 55 Minutes October 17th, 2018 1. J. G. Quintel is thirty-six years old. He is an American voice actor, animator, television writer, producer and director. He is best known as the creator of the Cartoon Network series ‘Regular Show’, in which he also voiced the characters Mordecai and High Five Ghost. 2.My name is J.G. Quintel, and I’m the creator of ‘The Regular Show’. I grew up watching cartoons especially‘The Simpsons’, I didn’t miss an episode at all.‘The Simpsons’ was the one that my friends and I were quoting constantly. 3.I really liked drawing, and I liked art. For as long as I can remember, I never wanted to be anything else. When I found out that it’s actually something people do for a living, I decided that I wanted to do that. So I went to college, and now I’m doing it. 4.In school you had to make a film every year.So, I made a film that had Mordecai in itand Benson in it. And it really was like how we acted in school. All the “uuuh!” and “Hmm, hmm!Hmm!hmm!”, that is just me and my friends being idiots.Because of the animation, you can do anything. So, they could have been human but that would be kind of boring. All the characters from my films are not what they happen to be. If you get past the fact that Benson is a gumball machine, or that Pops is a lollipop, they are just normal people hanging out. -

THE JOHNS NEWS Pages VOLUME XXVIII—NO

Ten Ten Pages THE JOHNS NEWS Pages VOLUME XXVIII—NO. 26 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY AFTERNOON—JANUARY 25, 1917. $1.50 PER YEAR I DC1*LAF\ IIOHE HI HAS. TO BEtilN FLY t AMPAIOX. VIOLATES PROHATIO.N. ' P^laines (leBUojod the home of Mrs. Four reels showing the fly menace Judge Kelly S. Searl was here Sat Dora Hall in Duplain, Tluirsday night. ! will be run at the ('em theatre on urday to settle several chancery mat SILENT INVADEN Very little of the contents were saved. WANTS PORTABLE the evening of February 2, after the ters. Don C. Fitch was brought up on While the family was sitting in the ! regular show, under the auspices of the charge of violating his probation living room about 7:30 o ’clock, a roar the Civic League of the high schoii. by the alleged act of procuring liquor ing was heard in the kitchen and the Tills will precede the active caiuualgn in a wet territory and bringing it jack TAHS IN CITY wall around the chimney burst into TABERNACLE BUILT . which th^y are to make to externiin- IS WELUTTESDED to St. Johns -to t»e consumed by him CLUB IN CBUNTY flames. Mrs. Hall is the wife of the , ate the fly. John L. Burkhart of the self and a number of friends . He was ‘ late W. F. Hall, and has a daughter I state board of health at Ijanslng will released on his recognizance and the BOTH YOUNd AND OLD ARE ( ALL- DR. .M. r. KIKES MAKES PARTINfi and son, who were both at home at the • give a talk at the same time. -

November-Force-Source-2019.Pdf

FoRCE SoURCE VolumeTHE 6 Issue 11 | nov. 2019 Yellowstone Snowmobile Trips Thankful Tree 10th Annual Turkey Shoot Base Holiday Parade Season Rentals Night of Shenanigans MOUNTAIN HOME AFB, IDAHO 366 FSS Commander Lt Col Allyson Strickland 366 FSS Deputy Michael Wolfe Marketing Director Shelley Turner ADVERTISE WITH US! - Magazine Advertisements Commercial Sponsorship Alexis Denoyer - 6 ft Facility Monitors Coordinator - Tabletop Acrylics - and more! Graphic Design Jessica Gibbens SPONSOR EVENTS Marketing Clerk & Private Reagan Olsen - Presence at Base Events Organization Monitor - Access to 9,000+ people - and more! Web & Social Media Miranda Baxter Interested in reaching our military & civilian community? The Force Source Magazine is prepared by the 366th Force Support Squadron Marketing Department and is an unofficial publication of the Mountain Home Please contact: AFB community. Contents are not necessarily the official views of, nor endorsed Alexis Denoyer by, the US Government, the Department of Defense, or the 366th Wing. No federal endorsement of advertisers or sponsors intended. Information in this Commercial Sponsorship Coordinator magazine is current at the time of publication. All facility programs, event hours, prices, and dates are subject to change without notice. Contact each 208-828-4519 facility for the most up to date information. 1 Contents FOOD Hackers Bistro..........................................10 Jet Stream Java.......................................10 Strikers Grill.............................................10