Struggling for Ethnic Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Specification on Administrative Units – Guidelines

INSPIRE Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe D2.8.I.4 INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units – Guidelines Title D2.8.I.4 INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units – Guidelines Creator INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Date 2009-09-07 Subject INSPIRE Data Specification for the spatial data theme Administrative units Publisher INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Type Text Description This document describes the INSPIRE Data Specification for the theme Administrative units Contributor Members of the INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Format Portable Document Format (pdf) Source Rights public Identifier INSPIRE_DataSpecification_AU_v3.0.pdf Language En Relation Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) Coverage Project duration INSPIRE Reference: INSPIRE_DataSpecification_AU_v3.0.docpdf TWG-AU Data Specification on Administrative units 2009-09-07 Page II Foreword How to read the document? This guideline describes the INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units as developed by the Thematic Working Group Administrative units using both natural and a conceptual schema languages. The data specification is based on the agreed common INSPIRE data specification template. The guideline contains detailed technical documentation of the data specification highlighting the mandatory and the recommended elements related to the implementation of INSPIRE. The technical provisions and the underlying concepts are often illustrated by examples. Smaller examples are within the text of the specification, while longer explanatory examples are attached in the annexes. The technical details are expected to be of prime interest to those organisations that are/will be responsible for implementing INSPIRE within the field of Administrative units. -

Czech and Slovak

LETTER-WRITING GUIDE Czech and Slovak INTRODUCTION Republic, the library has vital records from only a few German-speaking communities. Use the This guide is for researchers who do not speak Family History Library Catalog to determine what Czech or Slovak but must write to the Czech records are available through the Family History Republic or Slovakia (two countries formerly Library and the Family History Centers. If united as Czechoslovakia) for genealogical records are available from the library, it is usually records. It includes a form for requesting faster and more productive to search these first. genealogical records. If the records you want are not available through The Republic of Czechoslovakia was created in the Family History Library, you can use this guide 1918 from parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. to help you write to an archive to obtain From Austria it included the Czech provinces of information. Bohemia, Moravia, and most of Austrian Silesia. From Hungary it included the northern area, which BEFORE YOU WRITE was inhabited primarily by Slovaks. The original union also included the northeastern corner of Before you write a letter to the Czech Republic or Hungary, which was inhabited mainly by Slovakia to obtain family history information, you Ukrainians (also called Ruthenians), but this area, should do three things: called Sub-Carpathian Russia, was ceded to the Soviet Republic of Ukraine in 1945. Since 1993, C Determine exactly where your ancestor was the Czech Republic and Slovakia have been two born, was married, resided, or died. Because independent republics with their own governments. most genealogical records were kept locally, you will need to know the specific locality where your ancestor was born, was married, resided for a given time, or died. -

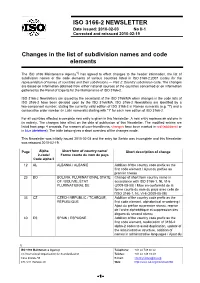

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Administrace Okres Kraj Územní Oblast Abertamy Karlovy Vary Karlovarský Kraj Plzeň Adamov Blansko Jihomoravský Kraj Brno Ad

Administrace Okres Kraj Územní oblast Abertamy Karlovy Vary Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Adamov Blansko Jihomoravský kraj Brno Adamov České Budějovice Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Adamov Kutná Hora Středočeský kraj Trutnov Adršpach Náchod Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtice Karviná Moravskoslezský kraj Ostrava Albrechtice Ústí nad Orlicí Pardubický kraj Jeseník Albrechtice nad Orlicí Rychnov nad Kněžnou Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtice nad Vltavou Písek Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Albrechtice v Jizerských horách Jablonec nad Nisou Liberecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtičky Nový Jičín Moravskoslezský kraj Ostrava Alojzov Prostějov Olomoucký kraj Brno Andělská Hora Bruntál Moravskoslezský kraj Jeseník Andělská Hora Karlovy Vary Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Anenská Studánka Ústí nad Orlicí Pardubický kraj Jeseník Archlebov Hodonín Jihomoravský kraj Brno Arneštovice Pelhřimov Vysočina Jihlava Arnolec Jihlava Vysočina Jihlava Arnoltice Děčín Ústecký kraj Ústí nad Labem Aš Cheb Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Babice Hradec Králové Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Babice Olomouc Olomoucký kraj Jeseník Babice Praha-východ Středočeský kraj Praha Babice Prachatice Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Babice Třebíč Vysočina Jihlava Babice Uherské Hradiště Zlínský kraj Zlín Babice nad Svitavou Brno-venkov Jihomoravský kraj Brno Babice u Rosic Brno-venkov Jihomoravský kraj Brno Babylon Domažlice Plzeňský kraj Plzeň Bácovice Pelhřimov Vysočina Jihlava Bačalky Jičín Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Bačetín Rychnov nad Kněžnou Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Bačice Třebíč Vysočina -

Bruno Kamiński

Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956) Bruno Kamiński Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 14 June 2016 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956) Bruno Kamiński Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Pavel Kolář (EUI) - Supervisor Prof. Alexander Etkind (EUI) Prof. Anita Prażmowska (London School Of Economics) Prof. Dariusz Stola (University of Warsaw and Polish Academy of Science) © Bruno Kamiński, 2016 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I <Bruno Kamiński> certify that I am the author of the work < Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956)> I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. -

The Evolution of the Party Systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic After the Disintegration of Czechoslovakia

DOI : 10.14746/pp.2017.22.4.10 Krzysztof KOŹBIAŁ Jagiellonian University in Crakow The evolution of the party systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic after the disintegration of Czechoslovakia. Comparative analysis Abstract: After the breaking the monopoly of the Communist Party’s a formation of two independent systems – the Czech and Slovakian – has began in this still joint country. The specificity of the party scene in the Czech Republic is reflected by the strength of the Communist Party. The specificity in Slovakia is support for extreme parties, especially among the youngest voters. In Slovakia a multi-party system has been established with one dominant party (HZDS, Smer later). In the Czech Republic former two-block system (1996–2013) was undergone fragmentation after the election in 2013. Comparing the party systems of the two countries one should emphasize the roles played by the leaders of the different groups, in Slovakia shows clearly distinguishing features, as both V. Mečiar and R. Fico, in Czech Republic only V. Klaus. Key words: Czech Republic, Slovakia, party system, desintegration of Czechoslovakia he break-up of Czechoslovakia, and the emergence of two independent states: the TCzech Republic and the Slovak Republic, meant the need for the formation of the political systems of the new republics. The party systems constituted a consequential part of the new systems. The development of these political systems was characterized by both similarities and differences, primarily due to all the internal factors. The author’s hypothesis is that firstly, the existence of the Hungarian minority within the framework of the Slovak Republic significantly determined the development of the party system in the country, while the factors of this kind do not occur in the Czech Re- public. -

Data on Urban and Rural Population in Recent Censusespdf

. ~ . DATA ON URBAN AND RURAL POPULA'EION . IN RECENT CENSUSES ... I UNITED NATIONS POPULATION STUDIES, No. 8 D_ATA ON URBAN AND RURAL POPULATION IN RECENT CENSUSES Department of Social Affairs Department of Economic Affairs Population Division Statistical Office of the United Nations Lake Success, New York July 1950 .... ST/ SOA/Series A. Population Studies, No. 8 List of reports in this series to date : Reports on the Population of Trust Territories No. 1. The Population of W estem Samoa No. 2. The Population of Tanganyika Reports on Popub.tion Estimates No. 3. World Population Trends, 1920-1947 Reports on Methods of Population St:atist.ics No. 4. Population Census Methods No. 6. Fertility Data in Population Censuses No. 7. Methods of Using Census Statistics for the Calculation or Life Tables and Other Demographic Measures. With Application to the Population of Brazil. By Giorgio Mortara No. 8. Data on Urban and Rural Population in Recent Censuses Report• on Demographic Aspects of Mi.gration No. 5. Problems of Migration Statistics UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS S:ales No.: 1950 • Xlll • 4 · ~ FOREWORD The Economic and Social Council, at its fourth session, adopted a resolution requesting the Secretary-General of the United Nations to offer advice and assist ance to Member States, with a view to improving the comparability and quality of data to be obtained in the censuses of 1950 and proximate years (resolution 41 (IV), 29 March 1947). As part of the implementation of this resolution, a series of studies has been prepared on the methods of obtaining and presenting information in population censuses on the size and characteristics of the population. -

“The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria-Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898" (2019)

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2019 “The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria- Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898 Evan Haley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Haley, Evan, "“The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria-Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898" (2019). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 58. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/58 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 “The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria-Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898 The press is one of the cornerstones of American society. Their ability to record and influence the history of the United States has shown itself countless times throughout the country’s history, and although its power has moved through various mediums and time periods it remains a vital part of how Americans perceive themselves and the world around them. It is at once a mirror and a window; the problem is that this window is not always clear, and our mirror does not always show us the truth. The same was true in 1898. Newspapers were a vital source of information for almost all Americans. -

276 the Little Czech and the Great Czech Nation Ladislav Holy

The differences in the form of the socialist system, in the way in which it ended and in the process of political and economic transformation which is now taking 3 place in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, are the result of the different historical development of these countries and of the different cultures which are the product of this development. The aim of this book is to investigate the specific ways The Little Czech and The Great Czech Nation in which Czech cultural meanings and in particular the notion of Czech identity and Ladislav Holy the accompanying nationalist sentiments have affected life under communism, its overthrow, and the political and economic transformation of post-communist society. Introduction Culture and politics; discourse and text Most of the sociological and political-scientific writing on Central and Eastern In discussing the role of cultural meanings in the post-communist transformation Europe is still grounded in a sociological universalism (Kapferer 1988: 3) which treats of Czech society, I make a distinction between culture and discourse. Following the this region as a politically, economically, and, to some extent, even culturally line of thought developed, among others, by Geertz (1973), Schneider (1976, 1980), undifferentiated whole. Various Central and Eastern European countries up to 1989 and Spiro (1982), I understand culture as a system of collectively held notions, beliefs, had essentially the same political and economic system and at present are undergoing premises, ideas, dispositions, and understandings, This system is not something that what is again seen as essentially the same kind of transformation from a totalitarian is locked in people‟s heads but is embodied in shared symbols which are the main political system to democratic pluralism and from a centrally planned to a market vehicles through which people communicate their worldview, value orientations, and economy. -

Veronika Mikulová Polish Socio-Cultural Realities from The

Veronika Mikulová Polish socio-cultural realities from the perspective of the Czech-Polish relations Introduction The diploma thesis Czechophiles – Polish fascinations with Czechs and the Czech Republic, which includes the present paper, was written in 2012– 2013. Czechophilia, for the purposes of the study, has been defi ned as an intensive liking and sentiment for Czechs and the Czech Republic as well as for all things Czech. The data gathered in the theoretical part of the study have been taken from the studied literature on the subject, whereas the key material for the entire study consists of individual in-depth interviews. The respondents were volunteers acquired through advertisements on a Facebo- ok page devoted to Czechophiles and on a Czechophile blog. The survey covered 18 people from Warsaw between 24 and 50 years of age. The goal of the study is to describe the history of Czechophilia, the experiences of Czechophiles and their subjective perception of the phenomenon. The basic research question was: “How is the phenomenon of Czechophilia perceived by Czechophiles themselves?” The part titled “The socio-cultural context of the Polish realities” approximates some topics connected with Czechophilia and outlines a possible background of this microphenomenon. In the sum- mary of the thesis, Czechophiles are classifi ed as a subculture with a peculiar rhetorical discourse including myths about the Czech and Polish character and culture. 1.1. Self-characterization of Poles or Polishness Stereotypes are an inseparable part of social consciousness. Self-stereo- types are subjective stereotypes through which people perceive and judge themselves or their own group. -

Czechoslovakian Roots

CZECHOSLOVAKIAN ROOTS Olga K. Miller Born in Czechoslovakia. Resides in Salt Lake City, Utah. Professional writer and genealogist. Author. Many Americans, whose ancestors came from their English-speaking employers and Czechoslovakia, were inspired by Haley's neighbors. Thus became Fox; Roots, but they visualize the task of Prochazka, Walker; Komarek, Marek; these ancestors as an insurmount Rericha, Cress, etc. Some tried to aid able They reason, "Why, the the situation by merely Americanizing the records there have probably been de spelling of their surname so it would stroyed by revolutions, wars, and the sound as it did originally. So Cerny hands of foreign invaders", or "They are became Czerny; Jelinek, Yellineck, etc. not accessible", etc.--anything to Unfortunately, in most instances, the justify their reluctance to even start. decision as to the correct spelling of Uttle do they know that their biggest any given surname can be made only by a task is to trace their lines back to the Czech native. But, on the other hand, one who arrived on American soil and then any Czechoslovakian with a feeling for to find his place of origin in spelling changes and some degree of Czechoslovakia. In other words, a lot linguistic education can figure out what has to be done before the research can be a misspelled or changed surname was begun in Czechoslovakia. originally. Most of our Czechoslovakian ancestors As in all research, in genealogy one came to America in the last century. starts with the known and proceeds to the Sane came earlier, but any traces of unknown. -

Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2003/1 The Szlonzoks and their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism TOMASZ KAMUSELLA BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2003 Tomasz Kamusella Printed in Italy in December 2003 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy ________Tomasz Kamusella________ The Szlonzoks1 and Their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism Tomasz Kamusella Jean Monnet Fellow, Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence, Italy & Opole University, Opole, Poland Please send any comments at my home address: Pikna 3/2 47-220 Kdzierzyn-Koïle Poland [email protected] 1 This word is spelt in accordance with the rules of the Polish orthography and, thus, should be pronounced as /shlohnzohks/. 1 ________Tomasz Kamusella________ Abstract This article analyzes the emergence of the Szlonzokian ethnic group or proto- nation in the context of the use of language as an instrument of nationalism in Central Europe. When language was legislated into the statistical measure of nationality in the second half of the nineteenth century, Berlin pressured the Slavophone Catholic peasant-cum-worker population of Upper Silesia to become ‘proper Germans’, this is, German-speaking and Protestant. To the German ennationalizing2 pressure the Polish equivalent was added after the division of Upper Silesia between Poland and Germany in 1922. The borders and ennationalizing policies changed in 1939 when the entire region was reincorporated into wartime Germany, and, again, in 1945 following the incorporation of Upper Silesia into postwar Poland.