(Linsun) by Krishna Prasad Chalise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security Bulletin 29

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 29, October 2010 The focus of this edition is on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain region Situation summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure* 26% This Food Security Bulletin covers the period July-September and is focused on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain (MFWHM) 24% region (typically the most food insecure region of the country). 22% July – August is an agricultural lean period in Nepal and typically a season of increased food insecurity. In addition, flooding and 20% landslides caused by monsoon regularly block transportation routes and result in localised crop losses. 18 % During the 2010 monsoon 1,600 families were reportedly 16 % displaced due to flooding, the Karnali Highway and other trade 14 % routes were blocked by landslides and significant crop losses were Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep reported in Kanchanpur, Dadeldhura, western Surkhet and south- 08 09 09 09 09 10 10 10 eastern Udayapur. NeKSAP District Food Security Networks in MFWHM districts Rural Nepal Mid-Far-Western Hills&Mountains identified 163 VDCs in 12 districts that are highly food insecure. Forty-four percent of the population in Humla and Bajura are reportedly facing a high level of food insecurity. Other districts with households that are facing a high level of food insecurity are Mugu, Kalikot, Rukum, Surkhet, Achham, Doti, Bajhang, Baitadi, Dadeldhura and Darchula. These households have both very limited food stocks and limited financial resources to purchase food. Most households are coping by reducing consumption, borrowing money or food and selling assets. -

Food Security Bulletin - 21

Food Security Bulletin - 21 United Nations World Food Programme FS Bulletin, November 2008 Food Security Monitoring and Analysis System Issue 21 Highlights Over the period July to September 2008, the number of people highly and severely food insecure increased by about 50% compared to the previous quarter due to severe flooding in the East and Western Terai districts, roads obstruction because of incessant rainfall and landslides, rise in food prices and decreased production of maize and other local crops. The food security situation in the flood affected districts of Eastern and Western Terai remains precarious, requiring close monitoring, while in the majority of other districts the food security situation is likely to improve in November-December due to harvesting of the paddy crop. Decreased maize and paddy production in some districts may indicate a deteriorating food insecurity situation from January onwards. this period. However, there is an could be achieved through the provision Overview expectation of deteriorating food security of return packages consisting of food Mid and Far-Western Nepal from January onwards as in most of the and other essentials as well as A considerable improvement in food Hill and Mountain districts excessive agriculture support to restore people’s security was observed in some Hill rainfall, floods, landslides, strong wind, livelihoods. districts such as Jajarkot, Bajura, and pest diseases have badly affected In the Western Terai, a recent rapid Dailekh, Rukum, Baitadi, and Darchula. maize production and consequently assessment conducted by WFP in These districts were severely or highly reduced food stocks much below what is November, revealed that the food food insecure during April - July 2008 normally expected during this time of the security situation is still critical in because of heavy loss in winter crops, year. -

Download 4.06 MB

Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report Project Number: 44214-024 Grant Number: 0357-NEP July 2020 Nepal: Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco-Regions Project Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental Compliance Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Government of Nepal Department of Forests and Soil Conservation Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco-Regions (BCRWME) Project (ADB Loan/Grant No.: GO357/0358-NEP) Semiannual Environemntal Monitoring Report of BCRWME Sub-projects (January to June 2020) Preparaed By BCRWME Project Project Management Unit Dadeldhura July, 2020 ABBREVIATION ADB : Asian Development Bank BCRWME : Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco- Regions BOQ : Bills of Quantity CDG : Community Development Group CFUG : Community Forest User Group CO : Community Organizer CPC : Consultation, Participation and Communications (Plan) CS : Construction Supervisor DDR : Due Diligence -

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

Khaptad Chhededaha Rural Municipality Invitation for Bids

Khaptad Chhededaha Rural Municipality Office Of The Municipal Executive Dogadi, Bajura Far-Western Province, Nepal Invitation for Bids IFB No: 1/075/076 Date of publication: 2075/12/29 Method of Procurement: NCB, Eligibility Procedure 1. Khaptad Chhetedaha Rural Municipality Office invites sealed Bids from all eligible Nepalese Bidders for Construction & Maintenance of Following Roads with construction detail as follows. (Name and Identification no of Contract are as follows.) Estimated Bid Cost Contract Bid S. Amount (NRS.) Security of Bid Identification Description of Work Security N. [Excluding VAT Validity Document No: amount & Contingencies] Period (NRs.) KCRM/NCB/ Chhededaha-Thamlekh 1 42,97,362.11 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/01/2075-076 Sadak Stharunnati KCRM/NCB/ Dungrikhola-Baddaune 2 43,06,503.61 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/02/2075-076 Sadak Stharunnati KCRM/NCB/ Adharikhola-Chhadipatal 3 43,05,041.53 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/03/2075-076 Sadak Stharunnati KCRM/NCB/ Atichaur-Chhededaha 4. 43,08,802.32 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/04/2075-076 Stharunnati Road Maurekhola- KCRM/NCB/ 5. Jayabageshwori-Raan- 87,94,058.32 2,55,000.00 last date of bid submission 3,000.00 W/R/05/2075-076 up to 120 days from the Validity Singada Sadak Stharunnati. 2. Eligible Bidders may obtain further information and inspect the Bidding Documents at the Khaptad-Chhededaha Rural Municipality office Bajura, Email Address: [email protected], Contact No: 096-690801 or may visit PPMO website www.bolpatra.gov.np. -

THE GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL of NEPAL Volume 8 -9 December 2010-2011 the GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL of NEPAL JOURNAL of NEPAL in This Issue

Volume 8-9 December 2010-2011 Volume 8-9 December 2010-2011 THE GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL OF NEPAL THE GEOGRAPHICAL THE GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL OF NEPAL JOURNAL OF NEPAL In this issue: Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Buildings in GIS Environment: Dhankuta Municipality, Nepal Basanta Paudel and Pushkar K Pradhan Socio-Economic Status of Dalits of the Western Tarai Villages, Nepal Bhoj Raj Kareriya School Dropout and its Relationship with Quality of Primary Education in Nepal Binay Kumar Kushiyait Community Forests Ensuring Local Governance and Livelihood: A Case Study in Sunwal VDC, A Journal Nawalparasi, Nepal Devi Prasad Paudel on Management and Economics Landholding Size and Educational and Occupational Status in Two Villages of Dang Volume 8 -9 December 2010-2011 8 -9 December Volume Dharani Kumar Sharma Role of Irrigation in Crop Production and Productivity: A Comparative Study of Tube Well and Canal Irrigation in Shreepur VDC of Kanchanpur District Narayan Prasad Paudyal Biodiversity and Livelihood of Pangre Jhalas Wetland, Morang District, Nepal Puspa Lal Pokhrel Persistent Change in Livelihoods in Bhirgaun, Eastern Nepal Shambhu P Khatiwada Hardships in Mountain Livelihood: Findings from Yari Village, Humla District Shiba Prasad Rijal The Activities Undertaken by the Central Department of Geography, Tribhuvan University: 2008-2011 Pushkar K Pradhan Central Department of Geography Central Department of Geography Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Faculty ofSHANKER Humanities DEV and CAMPUS Social Sciences Tel: 977-01-4330329, Fax: 977-1-4331319 Tribhuvan UniversityUniversity E-mail: [email protected] Kirtipur,Ramshah Kathmandu, Path, Kathmandu Nepal The Geographical Journal of Nepal The Geographical Journal of Nepal is a regular publication of the Central Department of Geography, Tribhuvan University. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Bajhang Bajura Doti Achham Kailali Seti, Bajhang Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Bajhang Bajura Doti Achham Kailali Seti, Bajura Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Field Bulletin

Issue No.: 01; April 2011 United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office FIELD BULLETIN Chaupadi In The Far-West Background Chaupadi is a long held and widespread practice in the Far and Mid Western Regions of Nepal among all castes and groups of Hindus. According to the practice, women are considered ‘impure’ during their menstruation cycle, and are subsequently separated from others in many spheres of normal, daily life. The system is also known as ‘chhue’ or ‘bahirhunu’ in Dadeldhura, Baitadi and Darchula, as ‘chaupadi’ in Achham, and as ‘chaukulla’ or ‘chaukudi’ in Bajhang district. Participants of training on Chaupadi-WCDO Doti Discrimination Against Women During Menstruation According to the Accham Women’s Development Officer (WDO), more Women face various discriminatory practices in the context of than 95% of women are practicing chaupadi. The tradition is that women cannot enter inside houses, chaupadi in the district. Women kitchens and temples. They also can’t touch other persons, cattle, and Child Development Offices in green vegetables and plants, or fruits. Similarly, women practicing Doti and Achham are chaupadi cannot milk buffalos or cows, and are not allowed to drink implementing an ‘Awareness milk or eat milk products. Programme against Chaupadi’. The programme is supported by Save Generally, women stay in a separate hut or cattle shed for 5 days the Children and covers 19 VDCs in during menstruation. However, those experiencing menstruation for Achham and 10 VDCs in Doti.In the the first time should, according to practice, remain in such a shed for VDCs targeted by this program, the at least 14 days. -

Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (Muan) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN)

Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (MuAN) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden European Sverige Union "This document has been financed by the Swedish "This publication was produced with the financial support of International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of does not necessarily share the views expressed in this MuAN, NARMIN, ADCCN and UCLG and do not necessarily material. Responsibility for its content rests entirely with the reflect the views of the European Union'; author." Publication Date June 2020 Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal (MuAN) National Association of Rural Municipality in Nepal (NARMIN) Association of District Coordination Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden Sverige European Union Expert Services Dr. Dileep K. Adhikary Editing service for the publication was contributed by; Mr Kalanidhi Devkota, Executive Director, MuAN Mr Bimal Pokheral, Executive Director, NARMIN Mr Krishna Chandra Neupane, Executive Secretary General, ADCCN Layout Designed and Supported by Edgardo Bilsky, UCLG world Dinesh Shrestha, IT Officer, ADCCN Table of Contents Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... -

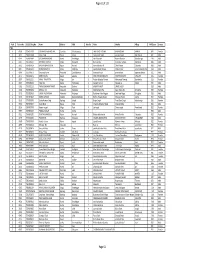

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal