Stillwater Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneficiation of Stillwater Complex Rock for the Production of Lunar Simulants

National Aeronautics and NASA/TM—2014–217502 Space Administration IS20 George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Huntsville, Alabama 35812 Beneficiation of Stillwater Complex Rock for the Production of Lunar Simulants D.L. Rickman Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama C. Young Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, Montana Tech, Butte, Montana D. Stoeser USGS, Denver, Colorado J. Edmunson Jacobs ESSSA Group, Huntsville, Alabama March 2014 The NASA STI Program…in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to the • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected advancement of aeronautics and space science. The papers from scientific and technical conferences, NASA Scientific and Technical Information (STI) symposia, seminars, or other meetings sponsored Program Office plays a key part in helping NASA or cosponsored by NASA. maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, technical, The NASA STI Program Office is operated by or historical information from NASA programs, Langley Research Center, the lead center for projects, and mission, often concerned with NASA’s scientific and technical information. The subjects having substantial public interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. English-language translations of foreign The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional scientific and technical material pertinent to mechanism for disseminating the results of its NASA’s mission. research and development activities. These results are published by NASA in the NASA STI Report Specialized services that complement the STI Series, which includes the following report types: Program Office’s diverse offerings include creating custom thesauri, building customized databases, • TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. -

Mineral Profile

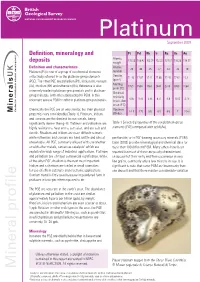

Platinum September 2009 Definition, mineralogy and Pt Pd Rh Ir Ru Os Au nt Atomic 195.08 106.42 102.91 192.22 101.07 190.23 196.97 deposits weight opme vel Atomic Definition and characteristics 78 46 45 77 44 76 79 de number l Platinum (Pt) is one of a group of six chemical elements ra UK collectively referred to as the platinum-group elements Density ne 21.45 12.02 12.41 22.65 12.45 22.61 19.3 (gcm-3) mi (PGE). The other PGE are palladium (Pd), iridium (Ir), osmium e Melting bl (Os), rhodium (Rh) and ruthenium (Ru). Reference is also 1769 1554 1960 2443 2310 3050 1064 na point (ºC) ai commonly made to platinum-group metals and to platinum- Electrical st group minerals, both often abbreviated to PGM. In this su resistivity r document we use PGM to refer to platinum-group minerals. 9.85 9.93 4.33 4.71 6.8 8.12 2.15 f o (micro-ohm re cm at 0º C) nt Chemically the PGE are all very similar, but their physical Hardness Ce Minerals 4-4.5 4.75 5.5 6.5 6.5 7 2.5-3 properties vary considerably (Table 1). Platinum, iridium (Mohs) and osmium are the densest known metals, being significantly denser than gold. Platinum and palladium are Table 1 Selected properties of the six platinum-group highly resistant to heat and to corrosion, and are soft and elements (PGE) compared with gold (Au). ductile. Rhodium and iridium are more difficult to work, while ruthenium and osmium are hard, brittle and almost pentlandite, or in PGE-bearing accessory minerals (PGM). -

New Mineral Names*,†

American Mineralogist, Volume 104, pages 625–629, 2019 New Mineral Names*,† DMITRIY I. BELAKOVSKIY1 AND FERNANDO CÁMARA2 1Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskiy Prospekt 18 korp. 2, Moscow 119071, Russia 2Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra “Ardito Desio”, Universitá di degli Studi di Milano, Via Mangiagalli, 34, 20133 Milano, Italy IN THIS ISSUE This New Mineral Names has entries for 8 new minerals, including fengchengite, ferriperbøeite-(Ce), genplesite, heyerdahlite, millsite, saranchinaite, siudaite, vymazalováite and new data on lavinskyite-1M. FENGCHENGITE* X-ray diffraction pattern [d Å (I%; hkl)] are: 7.186 (55; 110), 5.761 (44; 113), 4.187 (53; 123), 3.201 (47; 028), 2.978 (61; 135). 2.857 (100; 044), G. Shen, J. Xu, P. Yao, and G. Li (2017) Fengchengite: A new species with 2.146 (30; 336), 1.771 (36; 24.11). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data the Na-poor but vacancy-dominante N(5) site in the eudialyte group. shows the mineral is trigonal, space group R3m, a = 14.2467 (6), c = Acta Mineralogica Sinica, 37 (1/2), 140–151. 30.033(2) Å, V = 5279.08 Å3, Z = 3. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined to R = 0.043 for all unique I > 2σ(I) reflections. Fengchengite (IMA 2007-018a), Na Ca (Fe3+,) Zr Si (Si O ) 12 3 6 3 3 25 73 Fenchengite is the Fe3+ analog of eudialyte with a structural difference (H O) (OH) , trigonal, is a new eudialyte-group mineral discovered in 2 3 2 in vacancy dominant N5 site and splitting its Na site N1 into N1a and the agpaitic nepheline syenites and its pegmatite facies near the Saima N1b sites. -

STRATIFORM and ALLUVIAL Plafl NUM MINERALIZATION in THE

LU3 The Canadian M iner alog is t Vol. 33,pp. 1023-lM5(1995) STRATIFORMAND ALLUVIALPLAfl NUM MINERALIZATION IN THENEW CALEDONIA OPHIOLITE COMPLEX THIERRY AUGE lNI PIERREMATIRZOT BRGM'Metallogeny and Geotynarnics", B.P. 6009, 45060 Orldans Cedex 2, France ABSTRA T An unusualtype offt mineralizationhas beenfound in the New Caledoniaophiolite complex, associatedwitl stratiform chromite-bearingrocks at the baseof the cumulateseries (close to the transition zone betweendunite and pyroxene-bearing rocks) and with cbromite-richpyroxenite dykes from the samezone. Two placer deposis, both enrichedin Fl also have been recognized one derived from the chromite-rich horizons and the other a cbromitiferous beach sand of unknown origin. Chromite-bearingrocks aremarked by a very strongenrichment in Pt relative to fhe other platinum-groupelements (PGE), $'ith a rrardmunconcentration of 11.5ppm (average3.9 ppm). The Pt enrichmenttakes the form of platinum-groupminerals (PGM) included in chromite crystals and is interpretedas being pdlrar'/. The following minerals have been identified: ft-Fe{u alloys (isoferroplatinum,tulame€nite, tetraferroplatinum and undeterminedphases), cooperite, laurite, bowieite, malanite, cuprorhodsite,unnamed PGE oxides, and base-metalsulfides with PGE in solid solution. The associatedplacers show a slightly different mineral association,with isoferroplatinum,tulameenite, and rare cooperite,sperrylite, Os-k-Ru alloys and PGE oxides. A more complex paragenesishas been identified in the beach san4 with isoferroplatinum,cooperite, laurite, erlichmanite, Os-Ir-Ru alloys, bowieite, ba$ite, hollingworthire, sperrylite, stibiopalladinite, and unnamed Rh sulfide, Pt-Ru-Rh alloy and PGE oxides. This type of mineralization, which differs markedly from the Os-Ru-h mineralization previously recognized in podiform cbromitite in New Caledonia, shows several analogies with Alaskan-type PGE mineralization.The host chromitite,with typical cumulustextwes, is markedby Ti and Feh emichmentdue to derivationfrom an evolved liquid. -

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX- PROCESS OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT J.A. KINNAIRD, F.J. KRUGER, P.A.M. NEX and R.G. CAWTHORN INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND JOHANNESBURG CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT by J. A. KINNAIRD, F. J. KRUGER, P.A. M. NEX AND R.G. CAWTHORN (Department of Geology, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, P.O. WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa) ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 December, 2002 CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT ABSTRACT The mafic layered suite of the 2.05 Ga old Bushveld Complex hosts a number of substantial PGE-bearing chromitite layers, including the UG2, within the Critical Zone, together with thin chromitite stringers of the platinum-bearing Merensky Reef. Until 1982, only the Merensky Reef was mined for platinum although it has long been known that chromitites also host platinum group minerals. Three groups of chromitites occur: a Lower Group of up to seven major layers hosted in feldspathic pyroxenite; a Middle Group with four layers hosted by feldspathic pyroxenite or norite; and an Upper Group usually of two chromitite packages, hosted in pyroxenite, norite or anorthosite. There is a systematic chemical variation from bottom to top chromitite layers, in terms of Cr : Fe ratios and the abundance and proportion of PGE’s. Although all the chromitites are enriched in PGE’s relative to the host rocks, the Upper Group 2 layer (UG2) shows the highest concentration. -

Noritic Anorthosite Bodies in the Sierra Nevada Batholith

MINERALOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA, SPECIAL PAPER 1, 1963 INTERNATIONALMINERALOGICAL ASSOCIATION,PAPERS, THIRD GENERAL MEETING NORITIC ANORTHOSITE BODIES IN THE SIERRA NEVADA BATHOLITH ALDEN A. LOOMISl Department of Geology, Stanford University, Stanford, California ABSTRACT A group of small noritic plutons were intruded prior to the immediately surrounding granitic rocks in a part of the composite Sierra Nevada batholith near Lake Tahoe. Iron was more strongly concentrated in the late fluids of individual bodies than during the intrusive sequence as a whole. Pyroxenes are more ferrous in rocks late in the sequence, although most of the iron is in late magnetite which replaces pyroxenes. Both Willow Lake type and normal cumulative layering are present. Cumulative layering is rare; Willi ow Lake layering is common and was formed early in individual bodies. Willow Lake layers require a compositional uniqueness providing high ionic mobility to explain observed relations. The Sierran norites differ from those in large stratiform plutons in that (1) the average bulk composition is neritic anorthosite in which typical rocks contain over 20% AbO" and (2) differentiation of both orthopyroxene and plagioclase produced a smooth progressive sequence of mineral compositions. A plot of modal An vs. En for all the rocks in the sequence from early Willow Lake-type layers to late no rite dikes defines a smooth non-linear trend from Anss-En76 to An,,-En54. TLe ratio An/ Ab decreased faster than En/Of until the assemblage Anso-En65 was reached and En/Of began to decrease more rapidly. Similar plots for large stratiform bodies show too much scatter to define single curves. -

List of New Mineral Names: with an Index of Authors

415 A (fifth) list of new mineral names: with an index of authors. 1 By L. J. S~v.scs~, M.A., F.G.S. Assistant in the ~Iineral Department of the,Brltish Museum. [Communicated June 7, 1910.] Aglaurito. R. Handmann, 1907. Zeita. Min. Geol. Stuttgart, col. i, p. 78. Orthoc]ase-felspar with a fine blue reflection forming a constituent of quartz-porphyry (Aglauritporphyr) from Teplitz, Bohemia. Named from ~,Xavpo~ ---- ~Xa&, bright. Alaito. K. A. ~Yenadkevi~, 1909. BuU. Acad. Sci. Saint-P6tersbourg, ser. 6, col. iii, p. 185 (A~am~s). Hydrate~l vanadic oxide, V205. H~O, forming blood=red, mossy growths with silky lustre. Founi] with turanite (q. v.) in thct neighbourhood of the Alai Mountains, Russian Central Asia. Alamosite. C. Palaehe and H. E. Merwin, 1909. Amer. Journ. Sci., ser. 4, col. xxvii, p. 899; Zeits. Kryst. Min., col. xlvi, p. 518. Lead recta-silicate, PbSiOs, occurring as snow-white, radially fibrous masses. Crystals are monoclinic, though apparently not isom0rphous with wol]astonite. From Alamos, Sonora, Mexico. Prepared artificially by S. Hilpert and P. Weiller, Ber. Deutsch. Chem. Ges., 1909, col. xlii, p. 2969. Aloisiite. L. Colomba, 1908. Rend. B. Accad. Lincei, Roma, set. 5, col. xvii, sere. 2, p. 233. A hydrated sub-silicate of calcium, ferrous iron, magnesium, sodium, and hydrogen, (R pp, R',), SiO,, occurring in an amorphous condition, intimately mixed with oalcinm carbonate, in a palagonite-tuff at Fort Portal, Uganda. Named in honour of H.R.H. Prince Luigi Amedeo of Savoy, Duke of Abruzzi. Aloisius or Aloysius is a Latin form of Luigi or I~ewis. -

Geochemistry of the Mafic and Felsic Norite: Implications for the Crystallization History of the Sudbury Igneous Complex, Sudbury Ontario

Geochemistry of the Mafic and Felsic Norite: Implications for the Crystallization History of the Sudbury Igneous Complex, Sudbury Ontario G. R. Dessureau Mineral Exploration Research Centre, Department of Earth Sciences, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON, P3E 6B5 e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Whistle Embayment Geology The 1.85 Ga Sudbury Igneous Complex The Whistle Embayment occurs along the (SIC) is a 60 x 30 km layered igneous body NE margin of the basin under the Main Mass of the occupying the floor of a crater in northern Ontario. SIC and extends into the footwall as an Offset dyke The SIC comprises, from base to top: a (Whistle/Parkin Offset). Pattison (1979) and discontinuous unit of sulfide-rich, inclusion-bearing Lightfoot et al. (1997) provide detailed descriptions norite (Contact Sublayer), mafic norite, felsic of the embayment environment at Whistle. The norite, gabbro transition zones, and granophyre embayment contains up to ~300m of inclusion-rich, (Main Mass). Concentric and radial Quartz Diorite sulfide-bearing Sublayer in a well-zoned funnel Offset Dykes extend into the footwall rocks. extending away from the base of the SIC. Poikilitic, The distributions of the Sublayer and hypersthene-rich Mafic Norite occurs in and along associated Ni-Cu-PGE ores are controlled by the the flanks of the embayment as discontinuous morphology of the footwall: the Sublayer and lenses between the Sublayer and the Felsic Norite. contact ores are thickest within km-sized radial The Felsic Norite in the Whistle area ranges from depressions in the footwall referred to as ~450m thick adjacent to the embayment to >600m embayments (e.g., Whistle Embayment) and thick directly over the embayment. -

Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina by W

.'.' .., Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie RUTILE GUMMITE IN GARNET RUBY CORUNDUM GOLD TORBERNITE GARNET IN MICA ANATASE RUTILE AJTUNITE AND TORBERNITE THULITE AND PYRITE MONAZITE EMERALD CUPRITE SMOKY QUARTZ ZIRCON TORBERNITE ~/ UBRAR'l USE ONLV ,~O NOT REMOVE. fROM LIBRARY N. C. GEOLOGICAL SUHVEY Information Circular 24 Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie Raleigh 1978 Second Printing 1980. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: North CarOlina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development Geological Survey Section P. O. Box 27687 ~ Raleigh. N. C. 27611 1823 --~- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SECTION The Geological Survey Section shall, by law"...make such exami nation, survey, and mapping of the geology, mineralogy, and topo graphy of the state, including their industrial and economic utilization as it may consider necessary." In carrying out its duties under this law, the section promotes the wise conservation and use of mineral resources by industry, commerce, agriculture, and other governmental agencies for the general welfare of the citizens of North Carolina. The Section conducts a number of basic and applied research projects in environmental resource planning, mineral resource explora tion, mineral statistics, and systematic geologic mapping. Services constitute a major portion ofthe Sections's activities and include identi fying rock and mineral samples submitted by the citizens of the state and providing consulting services and specially prepared reports to other agencies that require geological information. The Geological Survey Section publishes results of research in a series of Bulletins, Economic Papers, Information Circulars, Educa tional Series, Geologic Maps, and Special Publications. -

Thirty-Fourth List of New Mineral Names

MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE, DECEMBER 1986, VOL. 50, PP. 741-61 Thirty-fourth list of new mineral names E. E. FEJER Department of Mineralogy, British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD THE present list contains 181 entries. Of these 148 are Alacranite. V. I. Popova, V. A. Popov, A. Clark, valid species, most of which have been approved by the V. O. Polyakov, and S. E. Borisovskii, 1986. Zap. IMA Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names, 115, 360. First found at Alacran, Pampa Larga, 17 are misspellings or erroneous transliterations, 9 are Chile by A. H. Clark in 1970 (rejected by IMA names published without IMA approval, 4 are variety because of insufficient data), then in 1980 at the names, 2 are spelling corrections, and one is a name applied to gem material. As in previous lists, contractions caldera of Uzon volcano, Kamchatka, USSR, as are used for the names of frequently cited journals and yellowish orange equant crystals up to 0.5 ram, other publications are abbreviated in italic. sometimes flattened on {100} with {100}, {111}, {ill}, and {110} faces, adamantine to greasy Abhurite. J. J. Matzko, H. T. Evans Jr., M. E. Mrose, lustre, poor {100} cleavage, brittle, H 1 Mono- and P. Aruscavage, 1985. C.M. 23, 233. At a clinic, P2/c, a 9.89(2), b 9.73(2), c 9.13(1) A, depth c.35 m, in an arm of the Red Sea, known as fl 101.84(5) ~ Z = 2; Dobs. 3.43(5), D~alr 3.43; Sharm Abhur, c.30 km north of Jiddah, Saudi reflectances and microhardness given. -

The Original Lithologies and Their Metamorphism

BASIC PLUTONIC INTRUSIONS OF THE RISÖR SÖNDELED AREA, SOUTH NORWAY: THE ORIGINAL LITHOLOGIES AND THEIR METAMORPHISM IAN C. STARMER Department of Geology, University of Nottingham, England Present address: Dept. of Geo/ogy, Queen Mary College, London, E. l STARMER, I. C.: Basic plutonic intrusions of the Risör-Sändeled area South Norway: The original Jithologies and their metamorphism Norsk Geologisk Tidsskri/1, Vol. 49, pp. 403-431. Oslo 1969. The emplacement of Pre-Cambrian basic intrusions is shown to have been a polyphase process and to have occurred Jargely between two major periods of metamorphism. The original igneous lithologies are discussed and a regional differentiation series is demonstrated, with changes in rock-type accompanied by some cryptic variation in the component minerals. Metamorphism after consolidation converted the intrusives to coronites and eaused partial amphibolitisation. Corona growths are described and attributed to essentially isochemical recrystal lisations in the solid-state, promoted by the diffusion of ions in inter granular fluids. The amphibolitisation of the bodies is briefly outlined, and it is concluded that the formation of amphibolite involved the intro duction of considerable amounts of extraneous water. The criterion for demoostrating the onset of amphibolitisation is thought to be the intemal replacement of pyroxene by homblende, contrasting with the replacement of plagioclase by various amphiboles during corona growth. Both amphibolites and coronites have been scapolitised, and this may have been an extended process which certainly continued after amphi bolitisation. Regional implications are considered and it is suggested that a !arge mass of differentiating magma may have underlain the whole region in Pre-Cambrian times. -

Platinum Group Minerals in Eastern Brazil GEOLOGY and OCCURRENCES in CHROMITITE and PLACERS

DOI: 10.1595/147106705X24391 Platinum Group Minerals in Eastern Brazil GEOLOGY AND OCCURRENCES IN CHROMITITE AND PLACERS By Nelson Angeli Department of Petrology and Metallogeny, University of São Paulo State (UNESP), 24-A Avenue, 1515, Rio Claro (SP), 13506-710, Brazil; E-mail: [email protected] Brazil does not have working platinum mines, nor even large reserves of the platinum metals, but there is platinum in Brazil. In this paper, four massifs (mafic/ultramafic complexes) in eastern Brazil, in the states of Minas Gerais and Ceará, where platinum is found will be described. Three of these massifs contain concentrations of platinum group minerals or platinum group elements, and gold, associated with the chromitite rock found there. In the fourth massif, in Minas Gerais State, the platinum group elements are found in alluvial deposits at the Bom Sucesso occurrence. This placer is currently being studied. The platinum group metals occur in specific Rh and Os occur together in minerals in various areas of the world: mainly South Africa, Russia, combinations. This particular PGM distribution Canada and the U.S.A. Geological occurrences of can also form noble metal alloys (7), and minerali- platinum group elements (PGEs) (and sometimes sation has been linked to crystallisation during gold (Au)) are usually associated with Ni-Co-Cu chromite precipitation of hydrothermal origin. sulfide deposits formed in layered igneous intru- In central Brazil there are massifs (Americano sions. The platinum group minerals (PGMs) are do Brasil and Barro Alto) that as yet are little stud- associated with the more mafic parts of the layered ied, and which are thought to contain small PGM magma deposit, and PGEs are found in chromite concentrations.