The Making and Un-Making of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge: a Case in Megaproject Planning and Decisionmaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transbay Terminal/Caltrain Downtown Extension

SCH No.95063004 City Project No. 2000.048E VOLUME I TRANSBAY TERMINAL / CALTRAIN DOWNTOWN EXTENSION / REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT in the City and County of San Francisco FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT/ ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT AND SECTION 4(f) EVALUATION Pursuant to National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, §102 (42 U.S.C. §4332); Federal Transit Laws (49 U.S.C. §5301(e), §5323(b) and §5324(b)); Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966 (49 U.S.C. §303); National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, §106 (16 U.S.C. §4700; 40 CFR Parts 1500-1508; 23 CFR Part 771; Executive Order 12898 (Environmental Justice); and California Environmental Quality Act, PRC 21000 etseq.; and the State of California CEQA Guidelines, California Administrative Code, 15000 et seq. by the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION and the CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, PENINSULA CORRIDOR JOINT POWERS BOARD, AND SAN FRANCISCO REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY March 2004 . ,- o c»uNrt I 1 *A#:II-04 rwr-7 ...41"EaLI.ii '». 1 =74=,./MB, Fl , r r-y=.rl .t*FIAA,fil, ,aae¥=<2* Beiwv Iald' 9"..1/5//2/ ea Acknowledgement This Final Environmental Impact Statement / Environmental Impact Report (Final EIS/EIR) was prepared in part from a grant of Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) and Transportation Congestion Relief Program (TCRP) funds received from the California Department of Transportation and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission. SCH No.95063004 City Project No. 2000.048E TRANSBAY TERMINAL / CALTRAIN DOWNTOWN EXTENSION / REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT in the City and County o f San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa C]ara Counties FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT/ ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT AND SECTION 4(f) EVALUATION Pursuant to National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. -

Urban Megaprojects-Based Approach in Urban Planning: from Isolated Objects to Shaping the City the Case of Dubai

Université de Liège Faculty of Applied Sciences Urban Megaprojects-based Approach in Urban Planning: From Isolated Objects to Shaping the City The Case of Dubai PHD Thesis Dissertation Presented by Oula AOUN Submission Date: March 2016 Thesis Director: Jacques TELLER, Professor, Université de Liège Jury: Mario COOLS, Professor, Université de Liège Bernard DECLEVE, Professor, Université Catholique de Louvain Robert SALIBA, Professor, American University of Beirut Eric VERDEIL, Researcher, Université Paris-Est CNRS Kevin WARD, Professor, University of Manchester ii To Henry iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My acknowledgments go first to Professor Jacques Teller, for his support and guidance. I was very lucky during these years to have you as a thesis director. Your assistance was very enlightening and is greatly appreciated. Thank you for your daily comments and help, and most of all thank you for your friendship, and your support to my little family. I would like also to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr Eric Verdeil and Professor Bernard Declève, for guiding me during these last four years. Thank you for taking so much interest in my research work, for your encouragement and valuable comments, and thank you as well for all the travel you undertook for those committee meetings. This research owes a lot to Université de Liège, and the Non-Fria grant that I was very lucky to have. Without this funding, this research work, and my trips to UAE, would not have been possible. My acknowledgments go also to Université de Liège for funding several travels giving me the chance to participate in many international seminars and conferences. -

The Third Crossing

The Third Crossing A Megaproject in a Megaregion www.thirdcrossing.org Final Report, February 2017 Transportation Planning Studio Department of City and Regional Planning, University of California, Berkeley Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of City and Regional Planning (DCRP) at the College of Environmental Design (CED) at UC Berkeley, the University of California Transportation Center and Institute of Transportation Studies (ITS), UC Berkeley for support. A special thanks also goes to the helpful feedback from studio instructor Karen Trapenberg Frick and UC Berkeley faculty and researchers including Jesus Barajas and Jason Corburn. We also acknowledge the tremendous support and insights from colleagues at numerous public agencies and non-profit organizations throughout California. A very special thanks goes to David Ory, Michael Reilly, and Fletcher Foti of MTC for their gracious support in running regional travel and land use models, and to Professor Paul Waddell and Sam Blanchard of UrbanSim, Inc. for lending their resources and expertise in land use modeling. We also thank our classmates Joseph Poirier and Lee Reis; as well as David Eifler, Teresa Caldeira, Jennifer Wolch, Robert Cervero, Elizabeth Deakin, Malla Hadley, Leslie Huang and other colleagues at CED; and, Alexandre Bayen, Laura Melendy and Jeanne Marie Acceturo of ITS Berkeley. About Us We are a team of 15 graduate students in City Planning, Transportation Engineering, and Public Health. This project aims to facilitate a conversation about the future of transportation between the East Bay and San Francisco and in the larger Northern California megaregion. We are part of the Department of City and Regional Planning in the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design, with support from the University of California Transportation Center and The Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. -

For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2008 with Comparisons to Prior Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2007 and June 30, 2006

Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board San Carlos, California A Joint Exercise of Powers Agreement among: City and County of San Francisco San Mateo County Transit District Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2008 PENINSULA CORRIDOR JOINT POWERS BOARD San Carlos, California Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2008 Prepared by the Finance Division This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Page I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal.....................................................................................................................i Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) Certificate of Achievement......................xi Board of Directors .................................................................................................................... xii Executive Management ........................................................................................................... xiii Organization Chart...................................................................................................................xiv Map............................................................................................................................................xv Table of Credits ........................................................................................................................xvi II. FINANCIAL SECTION INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT ...............................................................................1 -

For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 with Comparisons to Prior Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2015 and June 30, 2016

This Page Left Intentionally Blank PENINSULA CORRIDOR JOINT POWERS BOARD San Carlos, California Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 Prepared by the Finance Division This Page Left Intentionally Blank Table of Contents Page I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal ............................................................................................................................................ i Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) Certificate of Achievement ............................................. ix Board of Directors ............................................................................................................................................... x Executive Management ...................................................................................................................................... xi Organization Chart ........................................................................................................................................... xii Map ................................................................................................................................................................. xiii Table of Credits ................................................................................................................................................ xiv II. FINANCIAL SECTION INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT ...................................................................................................... 1 MANAGEMENT'S -

A Guide to the MTBTA Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Construction Photograph Collection

A Guide to the MTBTA Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Construction Photograph Collection TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview of the Collection Administrative Information Restrictions Administrative History Scope & Content Note Index Terms Series Description & Container Listing Archives & Special Collections College of Staten Island Library, CUNY 2800 Victory Blvd., 1L-216 Staten Island, NY 10314 © 2005 The College of Staten Island, CUNY Overview of the Collection Collection #: IC 1 Title: MTBTA Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Construction Photograph Collection Creator: Metropolitan Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Association Dates: 1960-1964 Extent: Abstract: This collection contains eleven photographs of the construction of the Verrazano- Narrows bridge. Administrative Information Preferred Citation MTBTA Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Construction Photograph Collection, Archives & Special Collections, Department of the Library, College of Staten Island, CUNY, Staten Island, New York. Acquisition These photographs were donated to the CSI Archives & Special Collections on October 26th, 2004 following their use in an exhibition at the college. Processing Information Restrictions Access Access to this record group is unrestricted. Copyright Notice The researcher assumes full responsibility for compliance with laws of copyright. The images are still the property of their creators, and requests for or use in publications should be directed to the Administrator of the MTA Special Archive, Laura Rosen. Laura Rosen Administrator, Special Archive MTBTA 2 Broadway, 22nd Floor New York, NY 646-252-7418 Administrative History The Verrazano-Narrows bridge was constructed in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, and was completed in November of 1964. It was built to permit the movement of vehicular traffic between Staten Island and Brooklyn and link parts of the Interstate Highway System. -

An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings

ctbuh.org/papers Title: An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing & Diagrid Systems Authors: Kheir Al-Kodmany, Professor, Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois Mir Ali, Professor Emeritus, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Subjects: Architectural/Design Structural Engineering Keywords: Structural Engineering Structure Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 5 Number 4 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany; Mir Ali International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of December 2016, Vol 5, No 4, 271-291 High-Rise Buildings http://dx.doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2016.5.4.271 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php An Overview of Structural and Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing and Diagrid Systems Kheir Al-Kodmany1,† and Mir M. Ali2 1Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL 60607, USA 2School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Abstract There is much architectural and engineering literature which discusses the virtues of exterior bracing and diagrid systems in regards to sustainability - two systems which generally reduce building materials, enhance structural performance, and decrease overall construction cost. By surveying past, present as well as possible future towers, this paper examines another attribute of these structural systems - the blend of structural functionality and aesthetics. Given the external nature of these structural systems, diagrids and exterior bracings can visually communicate the inherent structural logic of a building while also serving as a medium for artistic effect. -

Attachment C: Index of Transformative Projects & Strategies Submitted Project Names May Have Been Updated Slightly Since Submission

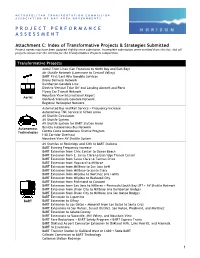

METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION ASSOCIATION OF BAY AREA GOVERNMENTS PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT Attachment C: Index of Transformative Projects & Strategies Submitted Project names may have been updated slightly since submission. Incomplete submissions were omitted from this list. Not all projects shown met the criteria for the Transformative Projects competition. Transformative Projects Aerial Tram Lines (San Francisco to North Bay and East Bay) Air Shuttle Network (Livermore to Central Valley) BART First/Last Mile Gondola Services Drone Delivery Network Dumbarton Gondola Line Electric Vertical Take Off and Landing Aircraft and Ports Flying Car Transit Network Mountain View International Airport Aerial Oakland/Alameda Gondola Network Regional Helicopter Network Automated Bus and Rail Service + Frequency Increase Autonomous TNC Service in Urban Areas AV Shuttle Circulators AV Shuttle System AV Shuttle System for BART Station Areas Autonomous Benicia Autonomous Bus Network Technologies Contra Costa Autonomous Shuttle Program I-80 Corridor Overhaul Mountain View AV Shuttle System AV Shuttles at Rockridge and 12th St BART Stations BART Evening Frequency Increase BART Extension from Civic Center to Ocean Beach BART Extension from E. Santa Clara to Eastridge Transit Center BART Extension from Santa Clara to Tasman Drive BART Extension from Hayward to Millbrae BART Extension from Millbrae to San Jose (x4) BART Extension from Millbrae to Santa Clara BART Extension from Milpitas to Martinez (via I-680) BART Extension from Milpitas to -

Sample Ballot and Voter Information Pamphlet General Election TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2010

Sample Ballot and Voter Information Pamphlet General Election TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2010 WARNING: THE LOCATION OF YOUR POLLING PLACE MAY HAVE CHANGED " # !! ! +%!0+7!0* .30!++.2 .,/+%2%+7.--%#22(%00.5%622. .30!-$)$!2%.0 %!130%(.)#% 1%+!#*.0+3%!++/.)-2%--+7 Right .0,.120!#%17.30#(.)#%)1 "32&.0.2(%017.3,!7"% !"+%2.4.2%&.025..02(0%% #!-$)$!2%1 Wrong .3#!-4.2%&.0&%5%0 #!-$)$!2%12(!-!++.5%$ $ $ &7.34.2%&.0 !-$)$!2%12(!-!++.5%$ 7.304.2%1)-2(!20!#% 5)++ 8-+74.2%1&.050)2%)-#!-$)$!2%1!0%#.3-2%$.."2!)-!+)12.&2(% 0)2%-!-$)$!2%1#!++ .04)1)2.305%"1)2%!2555!#'.4.0'0.4 ! ! .,/+%2%+7.--%#22(%00.5%622.2(%0)2%)-)-% 00.5 YOU WILL RECEIVE THREE BALLOT CARDS Voters in the cities of Berkeley, Oakland and San Leandro will receive three ballot cards for the upcoming November 2, 2010 General Election. Ballots will consist of cards A, B and C. The ballot cards you will receive in the mail or at your polling place can be viewed in your voter information pamphlet or online at www.acgov.org/rov ADDITIONAL POSTAGE REQUIRED Important Note: An estimated minimum postage of 78¢ cents is Required to return your Vote By Mail ballot envelope by mail. 3BCN INFORMATION FOR VOTERS WITH DISABILITIES The Alameda County Registrar of Voters has made every effort to locate acces- sible polling places for all elections. The accessibility of your polling place is shown on the back cover of this sample ballot by the words, “YES” and “NO” print- ed below the disability symbol. -

A Strategy to Improve Public Transit with an Environmentally Friendly Ferry System

A Strategy to Improve Public Transit with an Environmentally Friendly Ferry System Final Implementation & Operations Plan July 2003 San Francisco Bay Area Water Transit Authority Dear Governor Davis and Members of the California Legislature: After two years of work, the San Francisco Bay Area Water Transit Finally, as the Final Program Environmental Impact Report (FEIR) Authority (WTA) is delivering an Implementation and Operations details, this system is environmentally responsible. Plan. It is a viable strategy to improve Bay Area public transit with an environmentally friendly ferry system. It is a well- From beginning to end, this plan is built on solid, conservative thought-out plan calling for a sensible transportation investment. technical data and financial assumptions. If the State of California It shows how the existing and new individual ferry routes can adopts this plan and it is funded, we can begin making expanded form a well-integrated water-transit system that provides good water transit a reality. connections to other transit. The current economy makes it tough to find funds for new When you enacted Senate Bill 428 in October 1999, the WTA programs, even those as worthy as expanded Bay Area water was formed and empowered to create a plan for new and expanded transit. The Authority understands the economic challenges it water transit services and related ground transportation faces and is already working hard to overcome that hurdle. terminal access services. It was further mandated that the Today, the Authority’s future is unclear, pending your consideration. Authority must study ridership demand, cost-effectiveness But the prospects for expanded Bay Area water transit — and and expanded water transit’s environmental impact. -

10 the San Francisco Bay Area Water Trail

SAN FRANCISCO BAY TRAIL AND SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA WATER TRAIL 2016 HIGHLIGHTS THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA WATER TRAIL A growing network of launching and landing sites for human-powered boats and beachable sail craft (kayak, SUP, kiteboards, etc.) encouraging the exploration of the historic, scenic, cultural and environmental richness of the 450-square-mile San Francisco Bay estuary. Major funding is provided by the State Coastal Conservancy. 30 $596,900 14 TOTAL WATER TRAIL GRANT FUNDS AWARDED TO DATE SITES DESIGNATED SITES DESIGNATED IN 2016 $490,400 $1,153,480 GRANT FUNDS AWARDED 2016 $’S LEVERAGED THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY TRAIL A planned 500-mile shoreline path around the entire San Francisco Bay running through all nine Bay Area counties and 47 cities, connecting schools, neighborhoods, jobs, and parks to the shoreline and to each other. Major funding is provided by the State Coastal Conservancy. MILES CONNECTED BY NEW 2016 350 10 47 SEGMENTS MILES COMPLETED MILES CONSTRUCTED IN 2016 $18,788,326 144 GRANT FUNDS AWARDED TO DATE TOTAL MILES PLANNED/ DESIGNED 64 $113,682,562 TOTAL MILES $’S LEVERAGED CONSTRUCTED TRAIL BAY 2016 SAN FRANCISCO BAY TRAIL HIGHLIGHTS 2.5 miles of new Bay Trail Bay Bridge East Span Pathway Completion of new trail along Silicon Valley Trail Loop Study adjacent to Sears Point Wetland connects to Yerba Buena Island Christie Avenue between Powell released in partnership with Ridge Restoration Area opens linking and Shellmound streets closes Trail and the City of San Jose to 2.5 miles of existing shoreline a small but significant gap to demonstrate GHG emissions Bay Trail at Sonoma Baylands in Emeryville reductions along the South Bay Trails network Bay Trail Design Guidelines Google completes resurfacing of First 2016 episode of Open Road Explore the Coast grant awarded and Toolkit released four miles of Bay Trail linking with Doug McConnell features for five additional Bay Trail smart Sunnyvale and Mountain View. -

Almas Tower 1 Almas Tower

Almas Tower 1 Almas Tower Almas Tower ﺑﺮﺝ ﺍﻟﻤﺎﺱ The Almas Tower General information Status Complete Type Commercial Location Dubai, United Arab Emirates Coordinates 25°04′08.25″N 55°08′28.34″E Construction started 2005 Completed 2008 Opening 2009 Height [1] Architectural 360 m (1,181 ft) [1] Top floor 279.3 m (916 ft) Technical details [1] Floor count 74 (68 above ground, 5 basement floors) [1] Floor area 160,000 m2 (1,700,000 sq ft) [1] Lifts/elevators 35 Design and construction Owner Dubai Multi Commodities Centre [1] Architect Atkins Middle East [1] Developer Nakheel Properties [1] Main contractor Taisei Corporation Almas Tower 2 Diamond Tower) is a supertall skyscraper in JLT Free Zone Dubai, United Arab ﺑﺮﺝ ﺍﻟﻤﺎﺱ :Almas Tower (Arabic Emirates. Construction of the office building began in early 2005 and was completed in 2009 with the installation of some remaining cladding panels at the top of the tower. The building topped out at 360 m (1,180 ft) in 2008, becoming the third-tallest building in Dubai, after Emirates Park Towers and Burj Khalifa. Almas Tower has 74 floors, 70 of which are commercial alongside four service floors. The tower is located on its own artificial island in the centre of the Jumeirah Lakes Towers Free Zone scheme, the tallest of all the buildings on the development when completed. It was designed by Atkins Middle East, who designed most of the JLT Free Zone complex. The tower is being constructed by the Taisei Corporation of Japan in a joint venture with ACC (Arabian Construction Co.) who were awarded the contract by Nakheel Properties on 16 July 2005.[2] Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC), the owner of the tower, was the first to move in.