Copyright by Shannon Nicole Hicks 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

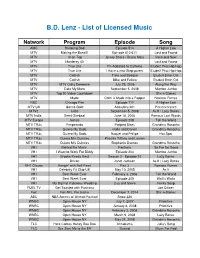

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

To View & Download My Resume

NAWARA BLUE Producer Driven, organized, detail- WORK EXPERIENCE oriented, and creative professional with extensive Roll Up Your Sleeves (2021 COVID Vaccination Special)- Producer NBC/ Camouflage Films, Inc. (Houston, TX) experience in television production. Skillset includes Put A Ring On It (Season 2)- Supervising Field Producer cultivating stories, tracking OWN / Lighthearted ENT (Atlanta, GA) multiple storylines, producing and directing large cast. Skilled Ready to Love (Season 4)- Supervising Field Producer OWN / Lighthearted ENT (Houston, TX) in talent and crew management, control room and Self Employed (Pilot)- Supervising Field Producer floor producing, and directing Magnolia / Red Productions (Dallas, TX) multiple cameras. Experienced in conducting and writing formal Supa Girlz (Season 1 Documentary)- Supervising Field Producer interviews and OTFs. Proficient in HBO MAX / Film-45 (Miami, FL) scheduling, budgeting, casting, Bride & Prejudice (Season 2)- Supervising Producer clearing locations, writing hot TLC/ Kinetic Content (Atlanta, GA) sheets, outlines, beat sheets, creative decks, show bibles, and Little Women Atlanta (Season 6)- Senior Field Producer any other pertinent production Lifetime/ Kinetic Content (Atlanta, GA) documents. Look Me in The Eye (Pilot)- Senior Field Producer OWN/ Kinetic Content (Los Angeles, CA) Digital proficiencies include Microsoft Office, Google Drive, The American Barbeque Showdown (Season 1)- Field Producer and Social Media platforms. Netflix/ All 3 Media (Atlanta, GA) Love Is Blind (Season 1)- Field Producer EDUCATION Netflix/ Delirium TV, LLC (Atlanta, GA) WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY, DETROIT MI 2006-2010 Teen Mom 2 (Season 16)- Field Producer Bachelor of Arts, Public Relations MTV/ MTV (Orlando, FL) Member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc. Beta Mu Chapter Married at First Sight: Honeymoon Island (Season 1)- Field Producer Lifetime/ Kinetic Content (Los Angeles, CA & St. -

Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F. Miller University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Miller, A. F.(2015). Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3217 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDNECKAISSANCE: HONEY BOO BOO, TUMBLR, AND THE STEREOTYPE OF POOR WHITE TRASH by Ashley F. Miller Bachelor of Arts Emory University, 2006 Master of Fine Arts Florida State University, 2008 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mass Communications College of Information and Communications University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: August Grant, Major Professor Carol Pardun, Committee Member Leigh Moscowitz, Committee Member Lynn Weber, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Ashley F. Miller, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Although her name is not among the committee members, this study owes a great deal to the extensive help of Kathy Forde. It could not have been done without her. Thanks go to my mother and fiancé for helping me survive the process, and special thanks go to L. Nicol Cabe for ensuring my inescapable relationship with the Internet and pop culture. -

Ugens Tv-Tal

Seertal uge 9 (24. februar 2014 - 2. marts 2014) Eftertryk/citat må kun ske mod flg. kildeangivelse: "TNS Gallup TV-Meter" Klik her for at hente en udskriftsvenlig udgave i PDF-format (kræver Adobe Acrobat Reader). TNS Gallup måler hvert døgn på vegne af Danmarks Radio, TV 2/DANMARK, TV3, SBS Discovery Media, Turner Broadcasting, Viacom International Media Networks og The Walt Disney Company Nordic tv-seningen i Danmark i tv-husstande ved hjælp af tv-metre. I uge 9 har i alt 1019 husstande og 2119 personer deltaget i TV-Meter-systemet. Alle seertal i pressemeddelelsen er beregnet ud fra universet 3 år og derover, med mindre andet er anført. Det bemærkes at alle tal er LIVE + VOSDAL (Viewing On Same Day As Live) og beregnet som "net ratings". Hvor meget tv ser danskerne? I uge 9 så en gennemsnitsdansker på 3 år og derover i gennemsnit 21 timer og 06 minutters tv, hvoraf 14 timer og 09 minutter fandt sted i perioden 17.00-00.00. Hele døgnet, alle Kl. 17-24, alle 15-50 år Tmin Pct. Tmin Pct. Tmin Pct. 4t 28m 21 3t 05m 22 3t 48m 21 0t 25m 2 0t 15m 2 0t 42m 4 0t 50m 4 0t 34m 4 0t 11m 1 0t 04m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 04m 0 0t 44m 3 0t 15m 2 0t 29m 3 0t 11m 1 0t 07m 1 0t 06m 1 5t 08m 24 4t 11m 30 3t 19m 19 1t 00m 5 0t 42m 5 0t 39m 4 0t 18m 1 0t 11m 1 0t 23m 2 0t 25m 2 0t 18m 2 0t 16m 1 0t 21m 2 0t 07m 1 0t 15m 1 0t 12m 1 0t 07m 1 0t 04m 0 1t 09m 5 0t 48m 6 1t 34m 9 0t 36m 3 0t 27m 3 0t 51m 5 0t 22m 2 0t 12m 1 0t 25m 2 0t 25m 2 0t 17m 2 0t 17m 2 0t 03m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 42m 3 0t 25m 3 0t 49m 5 0t 24m 2 0t 16m 2 0t 32m 3 0t 20m 2 0t 13m 2 0t 27m 3 0t 03m 0 0t 01m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 17m 1 0t 06m 1 0t 16m 1 0t 05m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 03m 0 0t 10m 1 0t 06m 1 0t 14m 1 0t 09m 1 0t 05m 1 0t 10m 1 0t 03m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 01m 0 0t 00m 0 0t 01m 0 0t 03m 0 0t 02m 0 0t 06m 1 0t 01m 0 0t 01m 0 0t 00m 0 0t 09m 1 0t 03m 0 0t 05m 0 0t 03m 0 0t 01m 0 0t 04m 0 Andre 1t 56m 9 1t 06m 8 1t 42m 9 Total TV 21t 06m 100 14t 09m 100 17t 54m 100 Hvor mange ser kanalerne pr. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

Productions in Ontario 2006

2006 PRODUCTION IN ONTARIO with assistance from Ontario Media Development Corporation www.omdc.on.ca You belong here FEATURE FILMS – THEATRICAL ANIMAL 2 AWAY FROM HER Company: DGP Animal Productions Inc. Company: Pulling Focus Pictures ALL HAT Producers: Lewin Webb, Kate Harrison, Producer: Danny Iron, Simone Urdl, Company: No Cattle Productions Inc./ Wayne Thompson, Jennifer Weiss New Real Films David Mitchell, Erin Berry Director: Sarah Polley Producer: Jennifer Jonas Director: Ryan Combs Writers: Sarah Polley, Alice Munro Director: Leonard Farlinger Writer: Jacob Adams Production Manager: Ted Miller Writer: Brad Smith Production Manager: Dallas Dyer Production Designer: Kathleen Climie Line Producer/Production Manager: Production Designer: Andrew Berry Director of Photography: Luc Montpellier Avi Federgreen Director of Photography: Brendan Steacy Key Cast: Gordon Pinsent, Julie Christie, Production Designer: Matthew Davies Key Cast: Ving Rhames, K.C. Collins Olympia Dukakis Director of Photography: Paul Sarossy Shooting Dates: November – December 2006 Shooting Dates: February – April 2006 Key Cast: Luke Kirby, Rachael Leigh Cook, Lisa Ray A RAISIN IN THE SUN BLAZE Shooting Dates: October – November 2006 Company: ABC Television/Cliffwood Company: Barefoot Films GMBH Productions Producers: Til Schweiger, Shannon Mildon AMERICAN PIE PRESENTS: Producer: John Eckert Executive Producer: Tom Zickler THE NAKED MILE Executive Producers: Craig Zadan, Neil Meron Director: Reto Salimbeni Company: Universal Pictures Director: Kenny Leon Writer: Reto Salimbeni Producer: W.K. Border Writers: Lorraine Hansberry, Paris Qualles Line Producer/Production Manager: Director: Joe Nussbaum Production Manager: John Eckert Lena Cordina Writers: Adam Herz, Erik Lindsay Production Designer: Karen Bromley Production Designer: Matthew Davies Line Producer/Production Manager: Director of Photography: Ivan Strasburg Director of Photography: Paul Sarossy Byron Martin Key Cast: Sean Patrick Thomas, Key Cast: Til Schweiger Production Designer: Gordon Barnes Sean ‘P. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Tenino Parade Celebrates Completion of Capstones

Stepping Up for Cure The Agony of / Main 14 Lewis County Firefighters Train for Massive Stair Climb / Life 1 Defeat $1 Early Week Edition Tuesday, Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Feb. 3, 2015 Hot-Handed Ony National Problem Loggers Down Mules as C2BL Teams Local Frozen Food Company Hampered Jockey for Playoff Positioning / Sports 2 by Ongoing Port Slowdown / Main 3 Broker County Hopes to Recoup $800,000 Breaks Investment in Former Ammo Plant Super Bowl FINANCIAL IMPACT: Nosler The sudden closure of a Lewis County commission- nition manufacturer that ended Dreams Packwood ammunition factory ers in 2009 approved a loan of up being bought by Nosler of Will Pay on Lease for Two in January not only left 17 peo- $300,000 — which later be- Bend, Oregon, in 2013. More Years After Closing ple searching for a job, but it has came a grant — and another Nosler shuttered the plant for County Packwood Facility Lewis County officials looking for $800,000 to improve and in January, leaving buildings into how they can recoup their build two separate buildings at tailor-made for manufactur- Assessor By Christopher Brewer investment into the facility on a the Packwood Business Park for ing suddenly unused. The East [email protected] long-term basis. Silver State Armory, an ammu- please see AMMO, page Main 12 OUT OF LUCK: Centralia Woman Hoped to Attend Big Game, But Super Bowl Tickets Never Materialized Tenino Parade Celebrates By Dameon Pesanti [email protected] Dianne Dorey bought her Super Bowl tickets less than Completion of Capstones five minutes after the Se- ahawks won the NFC Champi- onship Game. -

Cinematic Specific Voice Over

CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES BATES MOTEL BTS A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS CHOZEN S1 --- IN THEATER "TURN OFF CELL PHONE" MESSAGE FX NETWORKS E!: BELL MEDIA WHISTLER FILM FESTIVAL TRAILER BELL MEDIA AGENCY FALLING SKIES --- CLEAR GAZE TEASE TNT HOUSE OF LIES: HANDSHAKE :30 SHOWTIME VOICE OVER BEST VOICE OVER PERFORMANCE ALEXANDER SALAMAT FOR "GENERATIONS" & "BURNOUT" ESPN ANIMANIACS LAUNCH THE HUB NETWORK JUNE STUNT SPOT SHOWTIME LEADERSHIP CNN NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL SUMMER IMAGE "LIFE" SHAW MEDIA INC. Page 1 of 68 TELEVISION --- VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT GENERIC :45 RED CARPET IMAGE FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY HAPPY DAYS FOX SPORTS MARKETING HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA MUCH: TMC --- SERENA RYDER BELL MEDIA AGENCY SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMPETITIVE CAMPAIGN DIRECTV DISCOVERY BRAND ANTHEM DISCOVERY, RADLEY, BIGSMACK FOX SPORTS 1 LAUNCH CAMPAIGN FOX SPORTS MARKETING LAUNCH CAMPAIGN PIVOT THE HUB NETWORK'S SUMMER CAMPAIGN THE HUB NETWORK ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT BRAG PHOTOBOOTH CBS TELEVISION NETWORK BRAND SPOT A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS Page 2 of 68 NBC 2013 SEASON NBCUNIVERSAL SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO ZTÉLÉ – HOSTS BELL MEDIA INC. ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN NICKELODEON HALLOWEEN IDS 2013 NICKELODEON HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA NICKELODEON KNIT HOLIDAY IDS 2013 NICKELODEON SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND CAMPAIGN BRAVO NICKELODEON SUMMER IDS 2013 NICKELODEON GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT --- LONG FORMAT "WE ARE IT" NUVOTV AN AMERICAN COACH IN LONDON NBC SPORTS AGENCY GENERIC: FBC COALITION SIZZLE (1:49) FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY PBS UPFRONT SIZZLE REEL PBS Page 3 of 68 WHAT THE FOX! FOX BROADCASTING CO. -

Natpe Daily • 1 ® January 22, 2012

134646 Video Age Day1 1/18/12 2:49 PM Page 1 WWW.VIDEOAGEDAILY.COM NATPE DAILY • 1 ® JANUARY 22, 2012 NATPE’s After Florida Gov’s Reach & Riches Cecile Frot-Coutaz Warm Welcome he most frequent pre-market ques- FMNA CEO Gets Top NATPE Honor By Rick Scott, Governor of Florida tion is “What will NATPE be like?,” ith Cecile Frot-Coutaz, NATPE now a symbolic gesture — and recognize t is a pleasure to welcome you to the Tso let’s start with some facts and fig- managed to kill the proverbial an executive with a background in inter- National Association of Television ures: Number of exhibiting companies Wtwo birds with one stone for its national television, which is NATPE’s IProgram Executives Conference and (which is different from the number of ninth annual Tartikoff Awards: Satisfy driving force. Exhibition in Miami, Florida. stands and/or suites) — about 300 from NATPE’s domestic agenda — basically The Awards ceremony will follow a Founded in 1964, the National 18 countries, excluding publications but cocktail reception held at the Association of Television Program including various divisions of the same Fontainebleau’s Glimmer Ballroom on Executives (NATPE) celebrates over 40 groups. VideoAge estimated that more Tuesday starting at 6 p.m. The other years of service to the ever-evolving glob- than 50 companies are participating international honoree is Fernando al television industry. NATPE provides its without stands, bringing the total num- Gaitán of Colombia’s RCN-TV (creator members with education, networking, ber of countries to 22. of Ugly Betty). On the domestic side, the professional enhancement and technolog- In a three-day, 30-working-hour peri- other honorees are: Dennis Swanson of ical guidance through year-round activi- od, NATPE has packed in 82 seminars, FOX Television Stations, who oversees ties and events. -

POPULAR DVD TITLES – As of JULY 2014

POPULAR DVD TITLES – as of JULY 2014 POPULAR TITLES PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) PG-13 After Earth (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent -

Hunt on for Bomber Set for Sunday Liquor County Commissioners to Accept Input on Idea Requested by Restaurants

1A WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Pat Summerall dies at 82 Summerall, famous for his deep, reso- tennis. He taught middle See related story, page 6A Area residents recall nant voice, called 16 Super Bowls as the school English, and always famed broadcaster who play-by-play announcer. He spent more remembered where he Summerall jumped out of the boat and than 40 years as the voice of the National came from, according to hightailed it to his truck -- wanting to leave was born and raised here. Football League. friends and family. the boat behind because the gnats were so By DEREK GILLIAM But before he was a nationally known One time, after a night bad, Kennon said. [email protected] broadcaster, Summerall was born and when the gnats were like “I told him to back the trailer up, and raised here in Lake City. Summerall a buzzing cloud at the that if he wanted to give the boat away, I Lake City’s own Pat Summerall passed He loved to fish on the Suwannee River, river, Summerall had had would take it,” he said. away Tuesday of heart failure. He was 82 but hated the sand gnats. He was all- enough, Summerall’s first cousin Mike years old. conference in football, basketball and Kennon said. SUMMERALL continued on 3A Hearing Hunt on for bomber set for Sunday liquor County commissioners to accept input on idea requested by restaurants. By DEREK GILLIAM [email protected] Sunday sales of liquor could soon be a reality in Columbia County as the coun- ty commission will hold a public hearing on the issue at Thursday’s meeting.