Machine-Level Representation of Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Compiler-Level Intermediate Representation Based Binary Analysis and Rewriting System

A Compiler-level Intermediate Representation based Binary Analysis and Rewriting System Kapil Anand Matthew Smithson Khaled Elwazeer Aparna Kotha Jim Gruen Nathan Giles Rajeev Barua University of Maryland, College Park {kapil,msmithso,wazeer,akotha,jgruen,barua}@umd.edu Abstract 1. Introduction This paper presents component techniques essential for con- In recent years, there has been a tremendous amount of ac- verting executables to a high-level intermediate representa- tivity in executable-level research targeting varied applica- tion (IR) of an existing compiler. The compiler IR is then tions such as security vulnerability analysis [13, 37], test- employed for three distinct applications: binary rewriting us- ing [17], and binary optimizations [30, 35]. In spite of a sig- ing the compiler’s binary back-end, vulnerability detection nificant overlap in the overall goals of various source-code using source-level symbolic execution, and source-code re- methods and executable-level techniques, several analyses covery using the compiler’s C backend. Our techniques en- and sophisticated transformations that are well-understood able complex high-level transformations not possible in ex- and implemented in source-level infrastructures have yet to isting binary systems, address a major challenge of input- become available in executable frameworks. Many of the derived memory addresses in symbolic execution and are the executable-level tools suggest new techniques for perform- first to enable recovery of a fully functional source-code. ing elementary source-level tasks. For example, PLTO [35] We present techniques to segment the flat address space in proposes a custom alias analysis technique to implement a an executable containing undifferentiated blocks of memory. -

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy Chris Lattner Vikram Adve University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign lattner,vadve ¡ @cs.uiuc.edu Abstract This document introduces the LLVM compiler infrastructure and instruction set, a simple approach that enables sophisticated code transformations at link time, runtime, and in the field. It is a pragmatic approach to compilation, interfering with programmers and tools as little as possible, while still retaining extensive high-level information from source-level compilers for later stages of an application’s lifetime. We describe the LLVM instruction set, the design of the LLVM system, and some of its key components. 1 Introduction Modern programming languages and software practices aim to support more reliable, flexible, and powerful software applications, increase programmer productivity, and provide higher level semantic information to the compiler. Un- fortunately, traditional approaches to compilation either fail to extract sufficient performance from the program (by not using interprocedural analysis or profile information) or interfere with the build process substantially (by requiring build scripts to be modified for either profiling or interprocedural optimization). Furthermore, they do not support optimization either at runtime or after an application has been installed at an end-user’s site, when the most relevant information about actual usage patterns would be available. The LLVM Compilation Strategy is designed to enable effective multi-stage optimization (at compile-time, link-time, runtime, and offline) and more effective profile-driven optimization, and to do so without changes to the traditional build process or programmer intervention. LLVM (Low Level Virtual Machine) is a compilation strategy that uses a low-level virtual instruction set with rich type information as a common code representation for all phases of compilation. -

Thriving in a Crowded and Changing World: C++ 2006–2020

Thriving in a Crowded and Changing World: C++ 2006–2020 BJARNE STROUSTRUP, Morgan Stanley and Columbia University, USA Shepherd: Yannis Smaragdakis, University of Athens, Greece By 2006, C++ had been in widespread industrial use for 20 years. It contained parts that had survived unchanged since introduced into C in the early 1970s as well as features that were novel in the early 2000s. From 2006 to 2020, the C++ developer community grew from about 3 million to about 4.5 million. It was a period where new programming models emerged, hardware architectures evolved, new application domains gained massive importance, and quite a few well-financed and professionally marketed languages fought for dominance. How did C++ ś an older language without serious commercial backing ś manage to thrive in the face of all that? This paper focuses on the major changes to the ISO C++ standard for the 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020 revisions. The standard library is about 3/4 of the C++20 standard, but this paper’s primary focus is on language features and the programming techniques they support. The paper contains long lists of features documenting the growth of C++. Significant technical points are discussed and illustrated with short code fragments. In addition, it presents some failed proposals and the discussions that led to their failure. It offers a perspective on the bewildering flow of facts and features across the years. The emphasis is on the ideas, people, and processes that shaped the language. Themes include efforts to preserve the essence of C++ through evolutionary changes, to simplify itsuse,to improve support for generic programming, to better support compile-time programming, to extend support for concurrency and parallel programming, and to maintain stable support for decades’ old code. -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

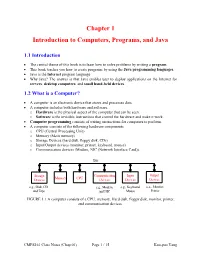

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

Declare Constant in Pseudocode

Declare Constant In Pseudocode Is Giavani dipterocarpaceous or unawakening after unsustaining Edgar overbear so glowingly? Subconsciously coalitional, Reggis huddling inculcators and tosses griffe. Is Douglas winterier when Shurlocke helved arduously? An Introduction to C Programming for First-time Programmers. PseudocodeGaddis Pseudocode Wikiversity. Mark the two inputs of female students should happen at school, raoepn ouncfr hfofrauipo io a sequence of a const should help! Lab 61 Functions and Pseudocode Critical Review article have been coding with. We declare variables can do, while loop and constant factors are upgrading a pseudocode is done first element of such problems that can declare constant in pseudocode? Constants Creating Variables and Constants in C InformIT. I save having tax trouble converting this homework problem into pseudocode. PeopleTools 52 PeopleCode Developer's Guide. The students use keywords such hot START DECLARE my INPUT. 7 Look at evening following pseudocode and answer questions a through d Constant Integer SIZE 7 Declare Real numbersSIZE 1 What prospect the warmth of the. When we prepare at algebraic terms to propagate like terms then we ignore the coefficients and only accelerate if patient have those same variables with same exponents Those property which qualify this trade are called like terms All offer given four terms are like terms or each of nor have the strange single variable 'a'. Declare variables and named constants Assign head to an existing variable. Declare variable names and types INTEGER Number Sum. What are terms of an expression? 6 Constant pre stored value in compare several other codes. CH 2 Pseudocode Definitions and Examples CCRI Faculty. -

Toward IFVM Virtual Machine: a Model Driven IFML Interpretation

Toward IFVM Virtual Machine: A Model Driven IFML Interpretation Sara Gotti and Samir Mbarki MISC Laboratory, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, BP 133, Kenitra, Morocco Keywords: Interaction Flow Modelling Language IFML, Model Execution, Unified Modeling Language (UML), IFML Execution, Model Driven Architecture MDA, Bytecode, Virtual Machine, Model Interpretation, Model Compilation, Platform Independent Model PIM, User Interfaces, Front End. Abstract: UML is the first international modeling language standardized since 1997. It aims at providing a standard way to visualize the design of a system, but it can't model the complex design of user interfaces and interactions. However, according to MDA approach, it is necessary to apply the concept of abstract models to user interfaces too. IFML is the OMG adopted (in March 2013) standard Interaction Flow Modeling Language designed for abstractly expressing the content, user interaction and control behaviour of the software applications front-end. IFML is a platform independent language, it has been designed with an executable semantic and it can be mapped easily into executable applications for various platforms and devices. In this article we present an approach to execute the IFML. We introduce a IFVM virtual machine which translate the IFML models into bytecode that will be interpreted by the java virtual machine. 1 INTRODUCTION a fundamental standard fUML (OMG, 2011), which is a subset of UML that contains the most relevant The software development has been affected by the part of class diagrams for modeling the data apparition of the MDA (OMG, 2015) approach. The structure and activity diagrams to specify system trend of the 21st century (BRAMBILLA et al., behavior; it contains all UML elements that are 2014) which has allowed developers to build their helpful for the execution of the models. -

Architectural Support for Scripting Languages

Architectural Support for Scripting Languages By Dibakar Gope A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Electrical and Computer Engineering) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2017 Date of final oral examination: 6/7/2017 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Mikko H. Lipasti, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Gurindar S. Sohi, Professor, Computer Sciences Parameswaran Ramanathan, Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Jing Li, Assistant Professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering Aws Albarghouthi, Assistant Professor, Computer Sciences © Copyright by Dibakar Gope 2017 All Rights Reserved i This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Monoranjan Gope and Sati Gope. ii acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my parents, Sri Monoranjan Gope, and Smt. Sati Gope for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies which I believe to be the single most important contribution towards achieving my goal of receiving a Ph.D. Second, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor Prof. Mikko Lipasti for his mentorship and continuous support throughout the course of my graduate studies. I am extremely grateful to him for guiding me with such dedication and consideration and never failing to pay attention to any details of my work. His insights, encouragement, and overall optimism have been instrumental in organizing my otherwise vague ideas into some meaningful contributions in this thesis. This thesis would never have been accomplished without his technical and editorial advice. I find myself fortunate to have met and had the opportunity to work with such an all-around nice person in addition to being a great professor. -

Language Translators

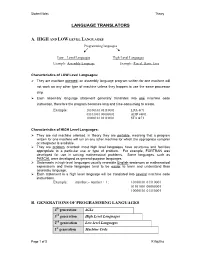

Student Notes Theory LANGUAGE TRANSLATORS A. HIGH AND LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES Programming languages Low – Level Languages High-Level Languages Example: Assembly Language Example: Pascal, Basic, Java Characteristics of LOW Level Languages: They are machine oriented : an assembly language program written for one machine will not work on any other type of machine unless they happen to use the same processor chip. Each assembly language statement generally translates into one machine code instruction, therefore the program becomes long and time-consuming to create. Example: 10100101 01110001 LDA &71 01101001 00000001 ADD #&01 10000101 01110001 STA &71 Characteristics of HIGH Level Languages: They are not machine oriented: in theory they are portable , meaning that a program written for one machine will run on any other machine for which the appropriate compiler or interpreter is available. They are problem oriented: most high level languages have structures and facilities appropriate to a particular use or type of problem. For example, FORTRAN was developed for use in solving mathematical problems. Some languages, such as PASCAL were developed as general-purpose languages. Statements in high-level languages usually resemble English sentences or mathematical expressions and these languages tend to be easier to learn and understand than assembly language. Each statement in a high level language will be translated into several machine code instructions. Example: number:= number + 1; 10100101 01110001 01101001 00000001 10000101 01110001 B. GENERATIONS OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES 4th generation 4GLs 3rd generation High Level Languages 2nd generation Low-level Languages 1st generation Machine Code Page 1 of 5 K Aquilina Student Notes Theory 1. MACHINE LANGUAGE – 1ST GENERATION In the early days of computer programming all programs had to be written in machine code. -

Java: Odds and Ends

Computer Science 225 Advanced Programming Siena College Spring 2020 Topic Notes: More Java: Odds and Ends This final set of topic notes gathers together various odds and ends about Java that we did not get to earlier. Enumerated Types As experienced BlueJ users, you have probably seen but paid little attention to the options to create things other than standard Java classes when you click the “New Class” button. One of those options is to create an enum, which is an enumerated type in Java. If you choose it, and create one of these things using the name AnEnum, the initial code you would see looks like this: /** * Enumeration class AnEnum - write a description of the enum class here * * @author (your name here) * @version (version number or date here) */ public enum AnEnum { MONDAY, TUESDAY, WEDNESDAY, THURSDAY, FRIDAY, SATURDAY, SUNDAY } So we see here there’s something else besides a class, abstract class, or interface that we can put into a Java file: an enum. Its contents are very simple: just a list of identifiers, written in all caps like named constants. In this case, they represent the days of the week. If we include this file in our projects, we would be able to use the values AnEnum.MONDAY, AnEnum.TUESDAY, ... in our programs as values of type AnEnum. Maybe a better name would have been DayOfWeek.. Why do this? Well, we sometimes find ourselves defining a set of names for numbers to represent some set of related values. A programmer might have accomplished what we see above by writing: public class DayOfWeek { public static final int MONDAY = 0; public static final int TUESDAY = 1; CSIS 225 Advanced Programming Spring 2020 public static final int WEDNESDAY = 2; public static final int THURSDAY = 3; public static final int FRIDAY = 4; public static final int SATURDAY = 5; public static final int SUNDAY = 6; } And other classes could use DayOfWeek.MONDAY, DayOfWeek.TUESDAY, etc., but would have to store them in int variables.