Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary English Version

THE HONG KONG MONETARY AUTHORITY Established in April 1993, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) is the government authority in Hong Kong responsible for maintaining monetary and banking stability. The HKMA’s policy objectives are • to maintain currency stability, within the framework of the Linked Exchange Rate system, through sound management of the Exchange Fund, monetary policy operations and other means deemed necessary • to promote the safety and stability of the banking system through the regulation of banking business and the business of taking deposits, and the supervision of authorized institutions • to enhance the efficiency, integrity and development of the financial system, particularly payment and settlement arrangements. Contents THE HKMA AND ITS FUNCTIONS 2 About The HKMA 12 Maintaining Monetary Stability 13 Promoting Banking Safety 14 Managing the Exchange Fund 15 Developing Financial Infrastructure REVIEW OF 2003 18 Chief Executive’s Statement 24 The Economic and Banking Environment in 2003 28 Monetary Conditions in 2003 30 Banking Policy and Supervisory Issues in 2003 32 Market Infrastructure in 2003 34 International Financial Centre 36 Exchange Fund Performance in 2003 37 The Exchange Fund 39 The HKMA: The First 10 Years The first part of this booklet introduces 46 Abbreviations the work and policies of the HKMA. The second part of the booklet is a 47 Reference Resources summary of the HKMA’s Annual Report for 2003. The full Annual Report is available on the HKMA website both in interactive form and on PDF files. Hard copies may also be purchased from the HKMA: see Reference Resources on page 47 for details. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

BANK of CHINA LIMITED (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People's Republic of China with Limited Liability) Global Offering of 25,568,590,000 Offer Shares

BOWNE OF HONG KONG 05/24/2006 06:09 NO MARKS NEXT PCN: 002.00.00.00 -- Page/graphics valid 05/24/2006 06:10BOM H00419 001.00.00.00 65 CONFIDENTIAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED (A joint stock company incorporated in the People's Republic of China with limited liability) Global Offering of 25,568,590,000 Offer Shares The Offer Shares are being offered by Bank of China Limited (the ""bank'' or ""we''): (i) outside the United States through BOCI Asia Limited, Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. and UBS AG acting through its business group, UBS Investment Bank, (in alphabetical order) and other purchasers named on page W-39 of this Offering Circular (collectively, the ""International Purchasers'') in accordance with Regulation S (""Regulation S'') under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the ""Securities Act''), and (ii) within the United States by certain of the International Purchasers through their respective selling agents to qualified institutional buyers as defined in Rule 144A under the Securities Act (""Rule 144A''). This International Offering (as defined on page W-11 of this Offering Circular) is part of a Global Offering (as defined on page W-11 of this Offering Circular) in which the bank is concurrently offering Offer Shares in Hong Kong through the Hong Kong Public Offering (as defined on page W-11 of this Offering Circular). The offer price per Offer Share is HK$2.95. The offer price excludes a brokerage fee, a trading fee imposed by The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the ""Hong Kong Stock Exchange''), and a transaction levy imposed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (the ""SFC''), which together amount to 1.01% of the offer price, and which shall be payable by investors. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University M crct. rrs it'terrjt onai A Be" 4 Howe1 ir”?r'"a! Cor"ear-, J00 Norte CeeD Road App Artjor mi 4 6 ‘Og ' 346 USA 3 13 761-4’00 600 sC -0600 Order Number 9238197 Selected literary letters of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1842-1853 Hurst, Nancy Luanne Jenkins, Ph.D. -

“The Silver Age”: Exhibiting Chinese Export Silverware in China Susan Eberhard

Concessions in “The Silver Age”: Exhibiting Chinese Export Silverware in China Susan Eberhard Introduction How do transcultural artifacts support global political agendas in post-socialist Chinese museums? In a 2018 state media photograph, a young woman gazes at a glittering silver compote, her fingertips pressed against the glass case.1 From an orthodox Chinese nationalist perspective on history, the photo of a visitor at The Silver Age: A Special Exhibition of Chinese Export Silver might present a vexing image of cultural consumption.2 “Chinese export silver” Zhongguo waixiao yinqi 中国外销銀器 is a twentieth-century collector’s term, translated from English, for objects sold by Chinese silverware and jewelry shops to Euro-American consumers.3 1 Xinhua News Agency, “Zhongguo waixiao yinqi liangxiang Shenyang gugong [China’s export silverware appears in Shenyang Palace Museum],” Xinhua中国外销银器 News February亮相沈阳故宫 6, 2018, accessed November 5, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/photo/2018- 02/06/c_129807025_2.htm (photograph by Long Lei ). 龙雷 2 Chinese title: Baiyin shidai—Zhongguo waixiao yinqi tezhan . A compote is a fruit stand, or a shallow dish with a stemmed base.白银时代—中国外银銀器特 The exhibition catalogue describes展 the object as a “built-up and welded grapevine fruit dish” (duihan putaoteng guopan ) and in English, “compote with welded grapevine design.” See Wang Lihua 堆焊葡萄藤果盤, Baiyin shidai—Zhongguo waixiao yinqi tezhan [The王立华 Silver Age: A Special Exhibition of Chinese Export Silver]白银时代———中国外销银器特展 (Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 2017), 73. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. The general introduction and section introductions of the exhibition and catalogue were bilingual, while the rest of the texts were only in Chinese; I have focused on the Chinese-language texts. -

The Risk Control of Qianzhuang

ISSN 1923-841X [Print] International Business and Management ISSN 1923-8428 [Online] Vol. 16, No. 2, 2018, pp. 38-47 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/10849 www.cscanada.org The Risk Control of Qianzhuang WANG Yanfen[a],* [a]Doctoral student. School of Economics, Central University of Finance was everywhere, and played an important role in the and Economics, Beijing, China. social economy and the modernization of China’s industry *Corresponding author. and commerce.1 Through the financial exchanges between Received 16 September 2018; accepted 22 November 2018 Qianzhuang and Qianzhuang, Qianzhuang and Piaohao Published online 26 December 2018 , Qianzhuang and domestic and foreign banks, a huge financial network was established to communicate Abstract cross-regional trade and foreign trade. As we can see, Qianzhuang is the traditional bank born in China. During Qianzhuang is one of the most representative forms of the late Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China, plenty of business development in China’s financial industry. It historical data proves that Qianzhuang has always been plays an indispensable role in the history of finance and a true financial service provider for Chinese agribusiness even economic history, as well as the transition from and commercial households. The control of deposit and traditional economy to modernization. loan risk in Qianzhuang is a concentrated expression of the The internal organization structure of Qianzhuang localization advantages of Qianzhuang, and it still has a is following the figure 1: eight butlers structure strong enlightenment for the risk control of contemporary . Apart from the manager and manager’s associates, other financial institutions. -

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

Reflections on Place and Place-Making in the Cities of China

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKIJURInternational Journal of Urban and Regional Research0309-1317© 2007 The Author. Journal Compilation © 2007 Joint Editors and Blackwell Publishing Ltd200731225779Original ArticlesReflections on places and place-making in ChinaJohn Friedmann Volume 31.2 June 2007 257–79 International Journal of Urban and Regional Research DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00726.x Reflections on Place and Place-making in the Cities of China JOHN FRIEDMANN Abstract This article is about the small spaces of the city we call ‘places’. Places are shaped by being lived in; they are spaces of encounter where the little histories of the city are played out. They are, of course, also shaped by the state through planning, supervision, ordinances, and so forth. The patterns and rhythms of life in the small spaces of the city are therefore not simply a straightforward projection of civil life. Places are also sites of resistance, contestation, and actions that are often thought to be illegal by the (local) state. After introducing the concept of place, the remainder of this article is a reflection on places and place-making (but also place-breaking) in urban China. Because the patterns and rhythms of urban life have continuity, however, my approach to their study was historical. The story told here is roughly divided into four major periods: Imperial China, Republican China, the People’s Republic under Mao Zedong, and the reform period from about 1980 onward. I then return to the concepts of place and place-making with which I began, summarizing my findings and suggesting some topics for further research. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

Stock Market and Economic Growth in China

Stock Market and Economic Growth in China Baotai Wang Department of Economics University of Northern British Columbia Prince George, British Columbia, Canada Tel: (250)960-6489 Fax: (250)960-5545 Email: [email protected] and D. Ajit Department of Economics University of Northern British Columbia Prince George, British Columbia, Canada Tel: (250)960-6484 Fax: (250)960-5545 Email: [email protected] ______________________________ The Authors wish to thank Dr. Gang Peng of Renmin University of China for his valuable comments on this study. However, the usual disclaimer applies. 1 Abstract This study investigates the impact of stock market development on economic growth in China. To this end, the quarterly data from 1996 to 2011 are used and the empirical investigation is conducted within the unit root and the cointegration framework. The results show that the relationship between the stock market development, proxied by the total market capitalization, and economic growth is negative. This result is consistent with Harris’ (1997) finding that the stock market development generally does not contribute positively to economic growth in developing countries if the stock market is mainly an administratively-driven market. Key Words: Stock Market, Economic Growth, Unit Root, Cointegration JEL Classification: G10, O1, O4, C22. 2 1. Introduction The impact of the stock market development on economic growth has long been a controversial issue. The theoretical debates generally focus on the increasing intermediation roles and functions of the stock market in promoting liquidity, mobilizing and pooling savings, generating information for potential investments and capital allocation, monitoring firms and exerting corporate control, and providing vehicles for trading, pooling and diversifying risks. -

Imagereal Capture

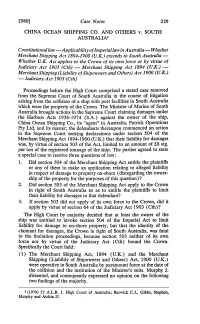

1980] Case Notes 229 CHINA OCEAN SHIPPING CO. AND OTHERS v. SOUTH AUSTRALIAl Constitutionallaw-ApplicabilityofImperial law in Australia-Whether Merchant Shipping Act 1894-1900 (U.K.) extends to South Australia Whether U.K. Act applies to the Crown of its own force or by virtue of Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) - Merchant Shipping Act 1894 (U.K.) Merchant Shipping (Liability 0/ Shipowners and Others) Act 1900 (U.K.) -Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) Proceedings before the High Court comprised a stated case removed from the Supreme Court of South Australia in the course of litigation arising from the collision of a ship with port facilities in South Australia which were the property of the Crown. The Minister of Marine of South Australia brought actions in the Supreme Court claiming damages under the Harbors Acts 1936-1974 (S.A.) against the owner of the ship, China Ocean Shipping Co., its "agent" in Australia, Patrick Operations Pty Ltd, and its master; the defendants thereupon commenced an action in the Supreme Court seeking declarations under section 504 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894-1900 (U.K.) that their liability for damages was, by virtue of section 503 of the Act, limited to an amount of £8 stg. per ton of the registered tonnage of the ship. The parties agreed to state a special case to resolve three questions of law: 1. Did section 504 of the Merchant Shipping Act entitle the plaintiffs or any of them to make an application relating to alleged liability in respect of damage to property on-shore (disregarding the owner ship of the property for the purposes of this question)? 2. -

Russo-Chinese Myths and Their Impact on Japanese Foreign Policy in the 1930S

Title Russo-Chinese Myths and Their Impact on Japanese Foreign Policy in the 1930s Author(s) Paine, S.C.M. Citation Acta Slavica Iaponica, 21, 1-22 Issue Date 2004 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/39429 Type bulletin (article) File Information ASI21_001.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP ACTA SLAVICA IAPONICA TOMUS 21, PP. 1-22 Articles RUSSO-CHINESE MYTHS AND THEIR IMPACT ON JAPANESE FOREIGN POLICY IN THE 1930S S.C.M. PAINE The Far Eastern geopolitical environment of the 1930s was characterized by systemic Chinese instability from an interminable civil war, growing Soviet missionary activities to promote communism, and a collapse of Asian trade brought on by the Great Depression. While Western attention remained rivet- ed on the more local problems of German compliance with the settlement terms of World War I and a depression that seemed to defy all conventional reme- dies, Japan focused with increasing horror on events in China. Japanese poli- cymakers had great difficulty communicating to their Western counterparts their sense of urgency concerning the dangers presented by the unfolding events in Asia. Their task was greatly complicated by the many myths obscuring the true nature of Russo-Chinese relations. These myths then distorted foreign understanding of Sino-Japanese relations. Russia is not usually considered in the context of the Far East. Both of its modern capitals – St. Petersburg and Moscow – are in Europe, its primary cul- tural ties are also with Europe, and yet much of its territory lies beyond the Ural Mountains in the Far East.