Memoirs of Lt Frank Wood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINALS Livards Given Class of '68 'O Outstanding Become Our Hiring Parades Newest Alumni

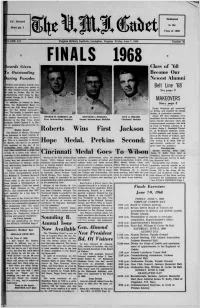

Dedicated G.C. Revised to tlie Story pg. 3 Class of 1968 •LUME LIV Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia. Friday, June 7, 1968 Number 30 X FINALS livards Given Class of '68 'o Outstanding Become Our hiring Parades Newest Alumni pi pliliiitiary and athletic awards were Resented to twenty-one cadets at Belt Line '68 Ae ftrst awards review parade of See page 3 "le year on Friday, May 24. The •esenitations were made by Miaj eneral George R. E. Shell, VMI iUperinitendent. MAKEOVERS y In addition ito honors in these Story page 2 elds, the Regimental Band re- eived the VMI Blood Donor Tro K Finals Weekend got underway >by for the fourth consecutivr on Friday and reached its climax 'ear. The trophy is awarded annu- Sunday at graduation exercises. •liy to the oadet company having' About 217 first classmen were GEORGE H. ROBERTS, JR. KENNETH J. PERKINS, GUY A. WILSON he highest percentage of contri- candidates for the baccalaureate de- First Jackson-Hope Medalist , Second Jackson-Hope Medalist Cincinnati Medalist •utionis to the Red Cross blood grees Sunday afternoon when the >rogram. Cadet Captain T. B. Bar- commencement ceremony was held on Jr. accepted the award for his in front of Preston Library at 2 company. o'clock. Judge J. Randolph Tucker Martin Award Roberts Wins First Jackson Jr. of Richmond Hustings Court, Th« Charles R. Martin. '55 award a VMI graduate and former presi- was presented to cadet Captain W dent of the Board of Visitors, gave P. Cobb, Echo company commiandi. the commencement address. Maj. er. -

THE GEORGE BYGONE – November2018: Another George Cavalryman (1914-18)

THE GEORGE BYGONE – November2018: Another George Cavalryman (1914-18) This month’s Bygone, unsurprisingly, looks at The George’s connection to the First World War, on the hundredth anniversary of its end. Albert James Hall, born at Easton on 19th Mar 1893, was the second son of Charles Hall, landlord of The George from about 1908 until 1924. Albert, who would already have been a member of the volunteer cavalry regiment, was called up to the 1/1st Battalion of the Essex Yeomanry on the12th of November 1914. He was sent to France as a member of C Squadron, the regiment travelling from Melton, where they had been encamped, via Woodbridge and Southampton to Le Havre arriving on the 1st December. The Yeomanry took a major part in what became known as the Battle for Frezenberg Ridge, part of the 2nd battle of Ypres, on May 13th 1915.The following, subsequently, appeared in the Essex Newsman on the 29th of May: “ ESSEX YEOMANRY ... STORIES OF SPLENDID GALLANTRY. In the last " Essex Newsman” we reported the heroic charge upon and capture of German trenches near Ypres by the Essex Yeomanry, in conjunction with the Horse Guards Blue, the Life Guards, and the 10th Hussars, on May 13. Unfortunately the casualty list was exceedingly heavy —the enemy shelling the Yeomanry in the captured trenches with great accuracy—but the deed was a noble one, will live in history, and is described by Brigadier-General B. Johnson as “the finest thing he has ever seen." The casualties the Essex Yeomanry numbered 163, out of 307 engaged.” The article also included a number of participants’ accounts including: Of the engagement itself, following three weeks of heavy fighting the Essex Yeomanry was moved into a support position at the strategically important Frezenberg Ridge. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Nile to Aleppo, with the Light-Horse in the Middle-East

NILE TO ALEPPO WITH THE LIGHT-HORSE IN THE MIDDLE-EAST BY HECTOR DINNING CAPTAIN, AUSTRALIAN ARMY ILLUSTRATED BY JAMES McBEY LONDON; GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD. RUSKIN HOUSE, 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C. 1 First published in 1920 TO THE LIGHT HORSEMEN OF AUSTRALIA AND TO THE HORSES WHO STOOD BY THEM THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED The Silk Bazaar at Damascus FOREWORD Someone ought to come forth from amongst the Light Horsemen of Australia and reveal them. This book will not reveal them; it is too personal. In any case the writer has not the faculty for revealing them. They scorn publicity; but someone ought to give it them—not for their sake, but for the sake of their Nation. Our Infantrymen in France have got to be known in the world. For one thing, they fought beside the British and Americans and French who acknowledged their worth and made it public. British acknowledgment of them alone has spread their fame. Most generous praise they have had from British General Headquarters. Nothing of the sort have the Light Horsemen had from a similar source in Egypt. Books have been written about our men in France. A party of British journalists was once invited to come and live with the Australian Corps there. The praise given by them was almost idealistic. Our Force in France has had Australian correspondents with it ever since it moved there; it was not until late, when the Sinai Campaign was over, that the Light-Horse got publicity through a correspondent. It is true that correspondent was appointed in time to do justice to their great dash in the last phase of the war in the Middle-East. -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

Rollofhonour WWII

TRINITY COLLEGE MCMXXXIX-MCMXLV PRO MURO ERANT NOBIS TAM IN NOCTE QUAM IN DIE They were a wall unto us both by night and day. (1 Samuel 25: 16) Any further details of those commemorated would be gratefully received: please contact [email protected]. Details of those who did not lose their lives in the Second World War, e.g. Simon Birch, are given in italics. Abel-Smith, Robert Eustace Anderson, Ian Francis Armitage, George Edward Born March 24, 1909 at Cadogan Square, Born Feb. 25, 1917, in Wokingham, Berks. Born Nov. 20, 1919, in Lincoln. Son of London SW1, son of Eustace Abel Smith, JP. Son of Lt-Col. Francis Anderson, DSO, MC. George William Armitage. City School, School, Eton. Admitted as Pensioner at School, Eton. Admitted as Pensioner at Lincoln. Admitted as State Scholar at Trinity, Trinity, Oct. 1, 1927. BA 1930. Captain, 3rd Trinity, Oct. 1, 1935. BA 1938. Pilot Officer, Oct. 1, 1938. BA 1941. Lieutenant, Royal Grenadier Guards. Died May 21, 1940. RAF, 53 Squadron. Died April 9, 1941. Armoured Corps, 17th/21st Lancers. Died Buried in Esquelmes War Cemetery, Buried in Wokingham (All Saints) June 10, 1944. Buried in Rome War Hainaut, Belgium. (FWR, CWGC ) Churchyard. (FWR, CWGC ) Cemetery, Italy. (FWR, CWGC ) Ades, Edmund Henry [Edmond] Anderson, John Thomson McKellar Armitage, Stanley Rhodes Born July 24, 1918 in Alexandria, Egypt. ‘Jock’ Anderson was born Jan. 12, 1918, in Born Dec. 16, 1902, in London. Son of Fred- Son of Elie Ades and the Hon. Mrs Rose Hampstead, London; son of John McNicol erick Rhodes Armitage. -

Egyptian Labor Corps: Logistical Laborers in World War I and the 1919 Egyptian Revolution

EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kyle J. Anderson August 2017 © 2017 i EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION Kyle J. Anderson, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This is a history of World War I in Egypt. But it does not offer a military history focused on generals and officers as they strategized in grand halls or commanded their troops in battle. Rather, this dissertation follows the Egyptian workers and peasants who provided the labor that built and maintained the vast logistical network behind the front lines of the British war machine. These migrant laborers were organized into a new institution that redefined the relationship between state and society in colonial Egypt from the beginning of World War I until the end of the 1919 Egyptian Revolution: the “Egyptian Labor Corps” (ELC). I focus on these laborers, not only to document their experiences, but also to investigate the ways in which workers and peasants in Egypt were entangled with the broader global political economy. The ELC linked Egyptian workers and peasants into the global political economy by turning them into an important source of logistical laborers for the British Empire during World War I. The changes inherent in this transformation were imposed on the Egyptian countryside, but workers and peasants also played an important role in the process by creating new political imaginaries, influencing state policy, and fashioning new and increasingly violent repertoires of contentious politics to engage with the ELC. -

British Troops in the Middle East, 1939-1944

British Troops in the Middle East 1939-1940 Troops in Egypt 9/30/39 HQ British Troops in Egypt (BTE) In the western desert The Armored Division (Egypt) - 7th Armored Division Heavy Armored Brigade 1st Royal Tanks 6th Royal Tanks Light Armored Brigade 7th Hussars 8th Hussars 11th Hussars Divisional Troops "M" Battery, 3rd RHA "C" Battery, 4th RHA 1st Kings Royal Rifle Corps 7th Infantry Division (at Mersa Matruh) 29th Infantry Brigade 2nd Scots Guards 1st Buffs Divisional Troops "P" Battery & 1 troop, 3rd RHA "D" Battery, 3rd RHA 2nd Field Company, RE 7th Division Signals 1st Northumberland Fusiliers (MG) 1st Hampshire Regiment In the Delta 18th Infantry Brigade 1st Bedfordshire and Hertforeshire Regiment 23rd Infantry Brigade 1st Royal Sussex Regiment 1st Essex Regiment (one coy in Cyprus) Alexandria Area 20th AA Battery,RA 3rd Coldstream Guards HQ 4th Indian Division 11th Indian Infnatary Brigade 4th Field Regiment, RA 2nd Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders 3rd Royal Horse Artillery, less "M" Battery and 1 troop 4th Royal Horse Artillery, less "C" Battery 7th Medium Regiment, RA 19th Heavy Battery (coastal) 42nd Field Company, RA 45th Fortress Company, RE 54th Field Company, RE Divisional Troops Royals Armored Car Regiment (1 sqn 5th Dragoon Guards under command; sailed for UK 11/30/39) Det/Royal Horse Artillery (sailed for UK 11/30/39) 12th Field Company, RE 1 Jerusalem Area 2nd King's Own 2nd Black Watch 2nd Highland Light Infantry Lydda Area Greys (1 sqn 4/7th Dragoon Guards under command, sailed for UK 11/30/39) Force Troops 17th Heavy Battery (Coastal) Det. -

History of the Eighth Illinois United States Volunteers

4* HISTORY **> OF THE JEiQbtb ITlUnotsXllmteo States Volunteers BY HARRY STANTON McCARD, B. S., HOSPITAL STEWARD, EIGHTH ILLINOIS U. S. VOLUNTEERS, AND HENRY TURNLEY , HOSPITAL STEWARD, EIGHTH ILLINOIS U. S. VOLUNTEERS. 1890. E. F HARMAN & CO., PUBLISHERS, CHICAGO. Governor John R. Tanner Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/historyofeighthilOOmcca John R. Tanner, the able and fearless executive of the great State of Illinois, who believes and who has the courage of his convictions, that it is the heart, the brain, the soul, not the skin, that go to determine manhood; who, acting upon this belief and upon the fundamental principle of this government that " taxation without representation is tyranny," had the manhood to appoint colored officers to com- mand a Colored Regiment, this book is affectionally dedicated BY THE AUTHORS. Colonel John K. Marshall COL. JOHN R. MARSHALL JOHN R. MARSHALL was born at Alexandria, Va., March 15, 1859. He was edu- Qj cated in the public schools of Alexandria, Va., and Washington, D. C. At the age of 16 he was apprenticed to the bricklayers trade, serving four years, until 1879, when he came to Chicago In 1 89 s he was appointed a deputy clerk in the County Clerk's office and held that position until he received his call to the front. Col. Marshall took an active part in the organization of the Ninth Battalion in 1891, be : ng elected Second Lieutenant, Company A in May, and First Lieutenant in July of the same year. In 1893 he was chosen Captain of his Company by an unanimous vote, and held that rank until he received his Colonel's commission in June, 1898. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 12-27-1900 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 12-27-1900 Santa Fe New Mexican, 12-27-1900 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 12-27-1900." (1900). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/7944 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANTA FE NEW MEXICAN, VOL. 37 SANTA FE, N. M., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 27, 1900. NO. 264 DISCUSSING TURKEY IN ANOTHER SCRAPE. NEW MEXICO OFFICIAL MATTERS. THE EDUCATIONAL Bny your Members of the British Maltreat- SURRENDER. Embassy SCHOOL OF MINES. LAND LEASISS APPROVED, ASSOCIATION. ed at Constantinople. Land Commissioner A. A. Keen to- Constantinople, December 26. Turk- day received thirty-tw- o school land ish soldiers grossly assaulted and mal- leases, approved by the secretary of the hnstmas Dewet, Steyn and Hassbroek May treated the British charge d'affaires, The Usefulness of This Institution interior. The land leased is located in The Opening Session Held in the Mr. De Bunsen, and other members of almost every of the The Gifts Down Their Arms Upon to the is no part territory. Court Boom the Lay the British embassy, in the vicinity of Territory Longer leases were forwarded to applicants to- Supreme at Certain Conditions. -

Strikes, Riots and Laughter

Middle East Centre STRIKES, RIOTS AND LAUGHTER AL-HIMAMIYYA VILLAGE’S EXPERIENCE OF EGYPT’S 1918 PEASANT INSURRECTION Alia Mossallam LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series | 40 | September 2020 About the Middle East Centre The Middle East Centre builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to develop rig- orous research on the societies, economies, polities and international relations of the region. The Centre promotes both specialised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area, and has out- standing strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE comprises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innovative research and training on the region. About the SMPM in the MENA Research Network Since the highly televised, tweeted and media- tised Arab uprisings, there has been a deluge of interest in social movements and contesta- tion from both inside and outside Middle East Studies, from the public, from policy-makers and from students. The LSE Middle East Centre has established the Social Movements and Popular Mobilisa- tion (SMPM) Research Network, which aims at bringing together academics and students undertaking relevant research. This network provides a platform for driving forward intel- lectual development and cutting-edge research in the field. As part of the network, a seminar series was set-up inviting academics to present their work. Papers are then published as part of the LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series. -

September 1940 - the Italian Invasion of Egypt

British and Commonwealth Orders of Battle http://www.rothwell.force9.co.uk/ September 1940 - The Italian Invasion of Egypt GHQ Middle East Forces: The Western Desert and Egypt - September 1940 GHQ Troops No 50 Middle East Commando Long Range Patrol Unit Western Desert Force Force Troops (Western Desert Force) 16th Heavy Antiaircraft Battery, RA one section 1st Light Antiaircraft Battery, RA less two troops (GHQ 4th Royal Horse Artillery less ‘C’ Battery 7th Medium Regiment, RA 2nd Field Company, RE 54th Field Company, RE 7th Armoured Division 11th Hussars (Prince Albert's Own) 2nd (Cheshire) Field Squadron, RE 141st Field Park Troop, RE 7th Support Group 'M' Battery, 3rd Royal Horse Artillery 'C' Battery, 4th Royal Horse Artillery 2nd Battalion, The Rifle Brigade 1st Battalion, The King's Royal Rifle Corps 4th Armoured Brigade 7th Queen's Own Hussars 6th Royal Tank Regiment 7th Armoured Brigade 8th (King's Royal Irish) Hussars 1st Royal Tank Regiment 4th Indian Infantry Division Central India Horse 3rd Royal Horse Artillery less ‘M’ Battery 1st Field Regiment, RA 31st Field Regiment, RA 4th (Bengal) Field Company, IE 12th (Madras) Field Company, IE 18th (Bombay)Field Company, IE 11th(Madras) Field Park Company, IE 1st Battalion, The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers MG battalion attached from WDF Troops 5th Indian Infantry Brigade 1st Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers 4th Battalion (Outram's), 6th Rajputana Rifles 3rd Battalion, 1st Punjab Regiment 11th Indian Infantry Brigade 2nd Battalion, The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders 1st Battalion