Abstract Suttell, Brian William

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 – 2015 Chapter Awards Submission June 1St, 2015

2014 – 2015 CHAPTER AWARDS SUBMISSION JUNE 1 ST, 2015 URBAN LEAGUE OF GREATER ATLANTA YOUNG PROFESSIONALS URBAN LEAGUE OF GREATER ATLANTA YOUNG PROFESSIONALS Distinguished Submission The Urban League of Greater Atlanta Young Professionals of the National Urban League Young Professionals submits hereby Tereance Puryear as a Distinguished: • President In good standing 100% Attendance on COP Calls 100% Attendance on Regional Calls 1,012 Total Volunteer Hours 120 Affiliate Volunteer Hours Conference Participation o NUL National Conference o LEAD[YP] o National Day of Service o National Day of Empowerment NULYP CHAPTER AWARDS APPLICATION YP Chapter Name: Urban League of Greater Atlanta Young Professionals YP President Name: Tereance R. Puryear Phone: 678-908-3356 Email Address: [email protected] Year Chapter Founded: 2001 Affiliate CEO Name: Nancy Flake Johnson Phone: 404-659-6575 Metrics 2013 - 2014 2014 - 2015 Number of Members (+28.75%) 160 206 Number of Chapter Volunteer Hours (+38.83%) 2,225 3,089 Number of Affiliate Service Hours (+9.6%) 1,944 2,122 Total Affiliate Dollars Given (+16.5%) $10,300 $12,000 Number of Corporate Sponsors (+20%) 5 6 Number of Community Service Events (+450%) 4 22 Number of Community Partners (+69.69%) 96 163 Number of Sister Chapters Supported 2 2 Award National Regional YP Regional Chapter Member Chapter National YP Chapter of Excellence X National Day of Service X National Day of Empowerment X Affiliate Service Chapter Award X Southern Region YP Chapter of X Excellence YP President Signature: on page 2 Affiliate/CEO Signature: on page 2 YP President Name: Tereance R. -

Race and Recreation in Charlotte, North Carolina, 1927-1973

‘PUBLIC ORDER IS EVEN MORE IMPORTANT THAN THE RIGHTS OF NEGROES’: RACE AND RECREATION IN CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA, 1927-1973 by Michael Worth Ervin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Sonya Ramsey ______________________________ Dr. Cheryl Hicks ______________________________ Dr. David Goldfield ii ©2015 Michael Worth Ervin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT MICHAEL WORTH ERVIN. “Public order is even more important than the rights of negroes:” race and recreation in Charlotte, North Carolina 1927-1973. (Under the direction of DR. SONYA RAMSEY) In July 1960, Charlotte’s Park and Recreation Commission enacted an official policy of desegregation in the city’s parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, and recreation centers. This development, which resulted in the first integrated municipal swimming pool in the state of North Carolina, seemed to embody the progressive business-centric ethos of Charlotte’s white elite. While token desegregation was lauded by commentators as evidence of Charlotte’s progressive race relations, the reality was far more complex. During the majority of the twentieth century, the Commission utilized a series of putatively moderate methods to suppress black dissent and muffle white reaction in the city. Even after de jure segregation crumbled, de facto segregation remained largely intact. This form of exclusion was buttressed by discriminatory public policies that redistributed black tax dollars to white communities, spatial segregation that insulated middle-and upper-class white neighborhoods from African Americans, and police harassment that fractured militant Black Power organizations. -

REEL INDEX (Charlotte Observers Clippings Microfilm)

1 CHARLOTTE OBSERVER CLIPPINGS FILE REEL INDEX REEL 1 (BOX 1) Babies – Jan. 1958 – Dec. 1970 Ballots - Election – July 1958 – Nov. 1970 Bank Robberies (General [& some U.S.]) – Apr. 1952 – Dec. 1969 (list of people committing robbery, time to be served, etc. from Apr. 1952 - July 1957 – then clippings start with Aug. 1958) Bank Robberies Charlotte – Aug. 1958 – Nov. 1969 Bank Robberies, N. C. – May 1956 – Dec. 1969 Bank Robberies, S. C. – July 1958 – Dec. 1969 Banking – Dec. 1956 – Dec. 1969 Elections, Primary & Regular Data – May 1958 – Dec. 1969 Elections North Carolina – May 1952 – Dec. 1970 (repeat of subject card with 1960) Election Presidential – Oct. 1956 – Dec. 1970 Elections Charlotte Municipal – Apr. 1943 – Nov. 1969 Elections Mecklenburg County – Feb. 1958 – Nov. 1969 Elections Mecklenburg State House of Representatives – Apr. 1960 – Dec. 1969 Elections - Mecklenburg State Senator – Feb. 1957 – Dec. 1969 Elections, Mecklenburg Precincts & Registrars – Oct. 1948 – Nov. 1969 Duke Power Co. – Oct. 1956 – Dec. 1969 REEL 2 (BOX 2) Charlotte Area Fund – Aug. 1963 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte City Council – Oct. 1944 – Dec. 1969 Duke Power Co. – Feb. 1963 (one clipping only – no subject announcement) Vietnam Negotiations – May 1967 – Dec. 1969 Park and Recreation Commission – Aug. 1942 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte City Parks – Apr. 1956 – Dec. 1969 Freedom Park – Aug. 1944 – May 1968 Charlotte Public Library Park - Mar. 1956 - May 1968 (now known as Arequipa Park - Nov. 1971) REEL 3 (BOX 3) Schools, Charlotte Mecklenburg School Systems – Dec. 1947 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte Police Dept. – Jan. 1950 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education (Sessions Laws) 1959 (Merger of City and County Systems) (Reprint of H. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-09553 CBS CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 51 W. 52nd Street New York, NY 10019 (212) 975-4321 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant's principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange 7.625% Senior Debentures due 2016 American Stock Exchange 7.25% Senior Notes due 2051 New York Stock Exchange 6.75% Senior Notes due 2056 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933). Yes ☒ No o Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

LSTA Grant Lesson Plan Writing Cohort Submitted by Rebecca Griffith, Isaac Bear Early College High School

William Madison Randall Library LSTA Grant Lesson Plan Writing Cohort Submitted by Rebecca Griffith, Isaac Bear Early College High School Overview Abstract Examine the work performed by the women and teenagers of the Women’s Good Will Committee of High Point, North Carolina as they labor to bridge race relations in their community. Explore primary source documents using close reading strategies. Discover how the work of the High Point Women’s Good Will Committee serves as a positive model for other groups to replicate. Extrapolate and apply the work of the High Point Women’s Good Will Committee to a current societal ill and seek areas in which adults and students can cooperatively find solutions to these problems. Standards AH2.H.4 – Analyze how conflict and compromise have shaped politics, economics and culture in the United States. AH2.H.5 – Understand how tensions between freedom, equality and power have shaped the political, economic and social development of the United States. AH2.H.7 – Understand the impact of war on American politics, economics, society and culture. Objectives AH2.H.4.1 – Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted (e.g., Populism, Progressivism, working conditions and labor unrest, New Deal, Wilmington Race Riots, Eugenics, Civil Rights Movement, Anti-War protests, Watergate, etc.). AH2.H.4.3 – Analyze the social and religious conflicts, movements and reforms that impacted the United States since Reconstruction in terms of participants, strategies, opposition, and results (e.g., Prohibition, Social Darwinism, Eugenics, civil rights, anti-war protest, etc.). -

Asparagus German Zep Nearing End of Ocean Flight

Fa q b r o u BTBm r ^ THURSDAY, M AY 7 ,198S,’ AVHRAin DAILT OBODLATION for the Meath of April, IMS The Park department yesterday Henry street property owned by The Lutnla choir of St John's and today recognised the coming of Alexander and Scmhle Mtkolowskl PoUah National church on Gtolway spring and neamesg 6f summer, was attawbed today by Deputy street wiU give a Balloon Dance In 5,846 ays ABOUTTOWN GOOD. Accident Tht E l A l * COB* Merabor^f the Audit 101 W voZ‘a*L M e Hew mowing the grass In the various Sheriff Leo Grenslnaki of Now Bri Pulaski hall on North street, Satur A MaeoaSTW eoa» parks and around municipally owned tain in favor of M. Krawsxyk and day night at 8 o'clock. Mlea Stella Bureau of OUeololloaa.' with Johns-Manvilic Building Materials Mancheater friends bave received property for the first time this sea Sons of New Britstn who are claim Rubacha and Mias Helen Ferrence Insurance F R ID A Y letters and cards from William J. son. ing $600 and coats o f suit. Martin who are In charge bave engaged the MANCHESTER — A Q TY OP VILLAGE CHARM Davis of Orchard street. Mr. Davis F. Stempten of New Britain is at Is Necessary 3 TO 6 SPECIALS Merry Cavaliers of New Britain to VOL. L V - NO. 188. (OaeeUtod Advartlaias oa Page is.) accompanied bis mother, who has torney for plalntlffe. play, and are planning for other The regular meeting of St. Mary's These Days Dtamond Brand MANCHESTER. -

The Failure of FCC Merger Reviews

DRAFT Not for attribution The Failure of FCC Merger Reviews: Communications Law Does Not Necessarily Perform Better than Antitrust Law Harold Furchtgott-Roth* Visiting Fellow American Enterprise Institute Prepared for Manhattan Institute Conference New York, New York December 9, 2002 Abstract: Antitrust law and communications law do not coexist well. The underlying premises of much of antitrust law makes little sense when the government sets prices, qualities of services, and reviews most if not all business decisions of a regulated firm. Yet the recent experience of the FCC’s review of mergers demonstrates that the FCC does a poor job as a surrogate antitrust agency. Not only are the FCC reviews redundant, they are costly, inefficient, and often lead to unlawful results. Consequently, antitrust law should not necessarily yield in the presence of communications law or other forms of regulatory law. * The views expressed are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Enterprise Institute which takes no positions on public policy matters. Parts of this paper draw heavily on material from my forthcoming booking, A Tough Act to Follow. -1- DRAFT Not for attribution The topic of this conference might be paraphrased as the role of antitrust law in a regulated industry. Of course, the two seemingly do not blend well. An underlying theme of several papers at this conference may be characterized as follows: in lawfully complying with government rules that regulate business practices, private businesses should not be liable for Sherman Act antitrust claims so long as the regulatory compliance is lawful. -

Georgia State 41, Shorter 7

2019 GSU FB Covers.indd 1 6/28/19 10:44 AM 2019 GSU FB Covers.indd 2 6/28/19 10:44 AM 2019 SCHEDULE Date Opponent .......................................................................................Time Aug. 31 at Tennessee .............................................................. ESPNU ...... 3:30 p.m. Sept. 7 FURMAN ............................................................ ESPN3 ...........7 p.m. Sept. 14 at Western Michigan ................................................ ESPN+ ............. 7 p.m. Sept. 21 at Texas State ............................................................................................. TBA Oct. 5 ARKANSAS STATE (Homecoming) ........................................... TBA Oct. 12 at Coastal Carolina ................................................................................... TBA Oct. 19 ARMY ............................................................................................... TBA Oct. 26 TROY ................................................................................................ TBA Nov. 9 at ULM ........................................................................................................... TBA Nov. 16 APPALACHIAN STATE.................................................................. TBA Nov. 23 SOUTH ALABAMA ......................................................................... TBA Nov. 30 at Georgia Southern ................................................................................. TBA 2019 GEORGIA STATE FOOTBALL #OurCity MEDIAINFORMATION GEORGIA -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

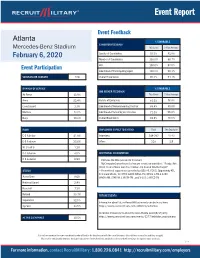

Event Report

Event Report Event Feedback Atlanta % FAVORABLE EXHIBITOR FEEDBACK Mercedes-Benz Stadium This Event 5 Year Average February 6, 2020 Quality of Candidates93.3% 91.8% Number of Candidates100.0% 86.7% Event Participation ROI100.0% 92.8% Likelihood of Participating Again100.0% 90.1% VETERAN JOB SEEKERS 336 Overall Experience93.3% 94.1% BRANCH OF SERVICE % FAVORABLE JOB SEEKER FEEDBACK Air Force 13.9% This Event 5 Year Average Army 52.4% Variety of Exhibitors81.2% 76.8% Coast Guard 1.3% Likelihood of Recommending the Fair88.4% 80.8% Marines 13.2% Likelihood of Securing an Interview71.0% 55.8% Navy 19.2% Overall Experience89.9% 76.5% RANK EMPLOYERS EXPECT TO EXTEND Total Per Employer E-5 & below 61.8% Interviews 549-767 10-13 E-6 & above 25.6% Offers 228 3.9 W-1 to W-5 1.2% 0-3 & below 4.5% ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 0-4 & above 6.9% -- DAV was the title sponsor for this event -- MyComputerCareer hosted a free pre-event seminar titled: "Ready, Aim, Hired: How to Make Sure Your Civilian Job Search Hits the Target" STATUS -- Promotional support was provided by CBS 46, FOX 5, Opportunity ATL, Entercom Media, 92.9 THE GAME WZGC-FM, NEWS & TALK 1380, Active Duty 9.6% WAOK-AM, STAR 94.1 WSTR-FM , and V-103.3 WVEE-FM National Guard 2.4% Reservist 7.2% Retired 33.7% FUTURE EVENTS Separated 32.5% Information about future RecruitMilitary events can be found here: Spouse 14.5% https://events.recruitmilitary.com/exhibitors/schedule Click here to learn more about the next Atlanta event (6/25/20): ACTIVE CLEARANCE 40.5% https://events.recruitmilitary.com/events/1277/exhibitor_registrations It is not uncommon for some candidates who attend to be displeased with the event because they did not secure the job they sought. -

Jackontheweb.Com 71

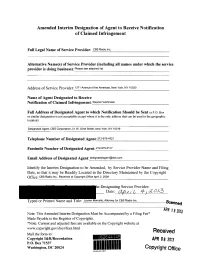

Amended Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement Full Legal Name of Service Provider: _C_BS_Ra_d_io_ln_c_,_____________ Alternative Name(s) of Service Provider (including all names under which the service provider is doing ~_P_le_a_se_s_ee_atta_ch_ed_l_is_t_______________ Address of Service Provider: 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Name of Agent Designated to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement:_w_a_yn_e_H_u_tch_in_s_on_____________ Full Address of Designated Agent to which Notification Should be Sent (a P,O, Box or similar designation is not acceptable except where it is the only address that can be used in the geographic location): Designated Agent, CBS Corporation, 51 W, 52nd Street, New York, NY 10019 Telephone Number of Designated 212-975-4321 Facsimile Number of Designated 212-975-0117 Email Address of Designated Agent:_d_es_ig_na_ted_ag_e_nt_@_c_bs_,c_om___________ Identify the Interim Designation to be Amended, by Service Provider Name and Filing Date, so that it may be Readily Located in the Directory Maintained by the Copyright Office: CBS Radio Inc" Received at Copyright Office April 2. 2009 he Designating Service Provider: Date: rlpA ['I, 4) Olo/3 Typed or Printed Name and Title: Lauren Marcelio, Attorney for CBS Radio Inc, Scanned Note: This Amended Interim Designation Must be Accompanied by a Filing Fee* 191013 Made Payable to the Register ofCopyrights. *Note: Current and adjusted fees are available on the Copyright website at www.copyright.gov/docs/fees.htmI Mail the form to: Received i62644145 Copyright I&RlRecordation APR 08 2013 P.O. Box 71537 Washington, DC 20024 162644145 Copyright Office Exhibit: CBS Radio Amended Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement 1. -

Transfer of Control to Shareholders of Entercom Communciations Corp. BTC-20170320AAR WAXY 30837 SOUTH MIAMI FL AM ENTERCOM MIAMI LICENSE, LLC JOSEPH M

. P. NS CORP. NS CORP. APPENDIX 2109 Transfer of Control to Shareholders Entercom Communciations Corp. ENTERCOM DENVER II LICENSE, LLC JOSEPH M. FIELD SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. M ENTERCOM MIAMI LICENSE, LLCMMM CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC. JOSEPH M. FIELDM CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC.M CBS RADIO EAST INC. CBS RADIO EAST INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS RADIO EAST INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. CBS BROADCASTING INC. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. SHAREHOLDERS OF ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. MMM CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.M CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.M CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.M CBS RADIO STATIONS INC. CBS RADIO STATIONS INC. CBS RADIO STATIONS INC.