ASPERGER's SYNDROME and FICTION – AUTISTIC WORLDS and THOSE WHO BUILD THEM by Ian Garbutt PHD by PRACTICE University of Stirli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

At the Library: April 2018

April 2018 Vol. 49 No. 4 In the Community Poetry: Here, There & Everywhere with Kids Celebrate National Poetry Month at the Library by finding books from your favorite poets, attending readings in the branches, taking part Dia de los Niños/ in writing workshops and stopping by a new exhibit at the Main Library featuring Dia de Los Libros striking photos of local poets alongside their work. Celebrate the 19th year Enjoy new Poet Laureate of Día de los Niños/ Kim Shuck’s wit and wisdom In These Years After Frog is Kissed Día de los Libros festival as she celebrates the launch of with book giveaways, by Kim Shuck Endangered Species, Enduring entertainment, live music, a visit from the Values, an anthology of prose, Before love lost childhood’s tale bookmobile and fun poetry and artwork from And left the protection of first stories activities for children. Poet Laureate Kim Shuck Bay Area creators. Attend her Home water photo: Christopher Felver Día de los Niños workshops for children and Bromeliad cup is a Mexican holiday teens and hear her and other writers speak at a baseball recognizing the importance and influence of Moon’s cherished trickster was obscured themed poetry jam. children in society. Started in New Mexico in 1997, For more information, visit sfpl.org or view the Now we raise the event soon gained national recognition and Practices eyes in 1999, the Library began its own celebration calendar of events on pages 3-6. bringing together many agencies to honor Endangered Species, Enduring Values – April 8, 1 p.m., Sing the spring children, literacy, culture and books. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing. -

Burlington (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Business Downsizing Online Auction - King Road

09/26/21 02:43:53 Burlington (Ontario, Canada) SELLER MANAGED Business Downsizing Online Auction - King Road Auction Opens: Wed, Jul 4 5:00pm ET Auction Closes: Thu, Jul 19 9:15pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 0001 Royal Doulton China Teacups & Saucers 0030 Vinyl Records Mix #3 0002 Autographed Puck ~ TONY ESPOSITO Hall of 0031 Vinyl Records Mix #4 Famer 0032 Vinyl Records Mix #5 0003 200 in 1 Science Project Lab 0033 Vinyl Records Mix #6 0004 Lot of Vintage 35mm Polaroid Film 0034 VINTAGE ORIGINAL BORDEN'S DAIRY 0005 Really Random ADVERTISEMENT 0006 Porcelain Figurines Collectibles 0035 Complete Randomness! 0007 SUPER NINTENDO VIDEO GAMES 0036 VINTAGE PHILCO 8 TRANSISTOR RADIO 0008 Tackle Box & Project Wood 0037 VINTAGE POCKET TRANSISTOR RADIO 0009 Lilly Apothecary Containers 0038 HUGE NINTENDO DS VIDEO GAMES 0010 JADE COY FISH PENDANT PACKAGE 0011 Vintage View-Master & Reels 0039 Magellan GPS unit 0012 VINTAGE DISNEY GOOFY & DONALD 0040 Kenwood Speakers DUCK 0041 TORONTO CN TOWER 3D PUZZLE 0013 Blue & White Porcelain Shoes 0042 Golf Themed Party Snack Tray (new) 0014 Instant Flea Market Booth Stock! 0043 2 12" Wood Ledges (new) 0015 VINTAGE STONEY CREEK DAIRY TRAY 0044 2 VINTAGE 80's MILK POSTERS 0016 Nautical Items 0045 BRONZE CEMETERY URN 0017 ANTIQUE BOOKS LOT 0046 RACLETTE & GRILL (NEW) 0018 Pair of Matching Lamps 0047 Hand Carved Wood Marlin Statue 0019 Bobble Heads Team Canada 1972 #1 0048 Hand Carved Pelican Statue 0020 Bobble Heads Team Canada 1972 #2 0049 CORGI SUPERMAN SUPERMOBILE 1979 0021 Hockey Bobble Heads #1 0050 FOLK ART HAND -

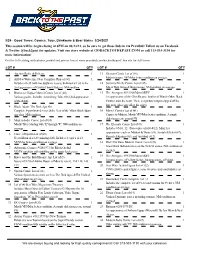

This Session Will Be Begin Closing at 6PM on 03/24/21, So Be Sure to Get Those Bids in Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

3/24 - Good Times: Comics, Toys, Drinkware & Beer Steins 3/24/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 03/24/21, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Rules & Policies 1 13 Shazam Comic Lot of (16) 1 Modern issues. VF/NM or better condition on average. 2 All-New Wolverine Near Complete Run of (36) 1 Includes #3-35 (with two duplicate issues) & Annual #1. #3 is the 14 Serenity/Firefly Comic Lot of (25) 1 2nd appearance of Gabby (Honey Badger). NM condition. Mix of Dark Horse & Boom issues. NM condition on average. 3 Bronze to Copper Marvel Comic Lot of (20) 1 15 The Avengers #52/1968/Marvel/KEY 1 Various grades. Includes Astonishing Tales #26 (2nd appearance 1st appearance of the Grim Reaper, brother of Wonder Man. Black of Deathlok). Panther joins the team. There is a picture/coupon clipped off the last page (does not affect the story). 4 Black Adam: The Dark Age Set 1 Complete 6-part limited series & the Year of the Villain Black Adam 16 Marvel Comics Lot of (61) 1 one-shot. NM condition. Copper to Modern. Mostly VF/NM or better condition. A couple older issues are around FN. 5 Modern Indie Comic Lot of (89) 1 Mostly Titles Starting with "E" through "F". -

The Diagnosis of Autism: from Kanner to DSM‑III to DSM‑5 and Beyond

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04904-1 S:I AUTISM IN REVIEW: 1980-2020: 40 YEARS AFTER DSM-III The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM‑III to DSM‑5 and Beyond Nicole E. Rosen1 · Catherine Lord1 · Fred R. Volkmar2,3 Accepted: 27 January 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract In this paper we review the impact of DSM-III and its successors on the feld of autism—both in terms of clinical work and research. We summarize the events leading up to the inclusion of autism as a “new” ofcial diagnostic category in DSM-III, the subsequent revisions of the DSM, and the impact of the ofcial recognition of autism on research. We discuss the uses of categorical vs. dimensional approaches and the continuing tensions around broad vs. narrow views of autism. We also note some areas of current controversy and directions for the future. Keywords Autism · History · Dimensional · Categorical · DSM It has now been nearly 80 years since Leo Kanner’s (1943) frst described by Kanner has changed across the past few classic description of infantile autism. Ofcial recognition of decades. When we refer to the concept in general, we will this condition took almost 40 years; several lines of evidence use the term autism, and when we refer to particular, ear- became available in the 1970s that demonstrated the valid- lier diagnostic constructs, we will use more specifc terms ity of the diagnostic concept, clarifed early misperceptions like autism spectrum disorder, infantile autism, and autistic about autism, and illustrated the need for clearer approaches disorder. -

The Stone Age Origins of Autism

Chapter 1 The Stone Age Origins of Autism Penny Spikins Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/53883 ‘Their strengths and deficits do not deny them humanity but, rather, shape their humanity’ Grinker 2010: 173 [in [1]] © 2013 Spikins; licensee InTech. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 4 Recent Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorders - Volume II 1. Introduction 1.1. Minds from a stone age past Our modern societies have been said to house ‘stone age minds’ (see [2]). That is to say that despite all the influences of modern culture our hard wired neurological make-up, instinc‐ tive responses and emotional capacities evolved in the vast depths of time which make up our evolutionary past. Much of what makes us ‘human’ thus rests on the nature of societies in the depths of prehistory thousands or even millions of years ago. Looking back on the archaeological record of the early stone age there is much to be proud of in our ancestry. Not only our remarkable intelligence but also our deep capacities to care about others and work together for a common good come from evolutionary selection on early humans throughout millions of years of the stone age. As far back as 1.6 million years ago we have archaeological evidence from survival of illnesses and trauma that those who were ill were looked after by others, and by the time of Neanderthals extensive care of the ill, infirm and elderly was common, see [3,4]. -

Wayland Free Public Library Strategic Plan 2020-2025

Wayland Free Public Library Strategic Plan 2020-2025 Approved by the Board of Library Trustees on September 18, 2019 Wayland envisions its Library as an essential resource for the Town, making ideas, information, and culture freely and easily available to all. Table of Contents Introduction, Purpose, Vision, and Mission ....................................................................................3 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................5 The Wayland Community and the Wayland Free Public Library .............................................6 Planning Methodology ....................................................................................................................... 10 User Needs Assessment ...................................................................................................................... 11 Strategic Goals and Theme ............................................................................................................... 12 Strategic Theme: Building Wayland Relationships .......................................................................... 12 Strategic Goals and Objectives (followed by start date for objectives) ........................................ 13 1. The Library Will Be an Essential Resource and Information Center ..................................... 15 2. Identify and Implement Improvements to Library Facilities ................................................... 17 3. The -

See 2019 Festival Program for Review

Celebrating 10 years in the Media Capital of the World September 5th - 9th September 5, 2018 Dear Friends: On behalf of the City of Los Angeles, welcome to the 2018 Burbank International Film Festival. Since 2009, the Burbank International Film Festival has promoted up-and-coming filmmakers from around the world by providing a gateway to expand their careers in the entertainment industry. I applaud the efforts of the Festival’s organizers and sponsors to create an event that generates an appreciation of storytelling through film. Thank you for your contributions to the vibrant artistic culture of Los Angeles. Congratulations to all the Industry Icon honorees. I send my best wishes for what is sure to be a successful and memorable event. Sincerely, ERIC GARCETTI Mayor September 5, 2018 Dear Friends, Welcome to the 2018 Burbank International Film Festival as we celebrate 10 successful years in "The Media Capitol of the World." The Burbank International Film Festival has given a platform to promising filmmakers, sharing their hard work with an eager audience and providing the means to expand their budding careers. As champions of independent filmmaking, the Festival organizers represent true benefactors to the colorful Los Angeles arts scene that we all enjoy. Congratulations to all the Festival honorees at this pivotal point in their careers. We appreciate your dedication and the contribution it makes to our arts culture. Sincerely, ANTHONY J. PORTANTINO Senator 25th Senate District Board of Directors Jeff Rector President / Festival Director Jeff is an award-winning filmmaker and working actor. His feature film “Revamped” which he wrote, directed and produced, is currently being distributed worldwide. -

Autism, Creativity and Aesthetics

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Autism, Creativity and Aesthetics Journal Item How to cite: Roth, Ilona (2018). Autism, Creativity and Aesthetics. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 17(4) pp. 498–508. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 Taylor Francis https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1080/14780887.2018.1442763 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 1 Autism, Creativity and Aesthetics Ilona Roth Affiliation Dr Ilona Roth, BA (Hons), DPhil, BA (Hons) Hum (Open), CPsychol, AFBPsS Senior Lecturer in Psychology, School of Life, Health and Chemical Sciences, The Open University Contact details School of Life, Health and Chemical Sciences, STEM Faculty, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK 7 6AA, United Kingdom [email protected] Biographical note Ilona Roth is Senior Lecturer in Psychology, School of Life Health and Chemical Sciences, The Open University. With background in cognitive psychology, she has teaching and research specialisms in autism. Roth’s longstanding personal and professional interest in the arts led her recently to complete a degree in Humanities and Romance languages. She is author of film, multi-media and written material on autism, including Roth et.al. (2010) ‘The Autism Spectrum in the 21st Century: Exploring Psychology, Biology and Practice’. -

Neurotribes 20/20

Neurotribes 20/20, (March 13, 1992). The Street Where They Lived. Part 1, ABC News 20/20, (March 20, 1992.). The Street Where They Lived. Part 2, ABC News A Tribute to Eric Schopler (1927–2006). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_THeWH0ox4 Adams, G. S. and Kanner, L. (1926). General Paralysis among the North American Indians: A Contribution to Racial Psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry Aichhorn, A. (1965). Wayward Youth. New York, NY: Penguin Books repr. ed. Aldiss, B. W. (1995). The Detached Retina: Aspects of SF and Fantasy. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press Allison, H. (1987). Perspectives on a Puzzle Piece. National AutisticSociety Aly, G. Chroust, P. and Pross, C. (1994). Cleansing the Fatherland: Nazi Medicine and Racial Hygiene, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press American Journal of Psychiatry, (1939). News and Notes. 96(3). 736–46 American Philosophical Society. Eugenics Record Office Records, 1670–1964 American-Austrian Foundation. The Medical Club—Billrothhaus: Epoch-Making Lectures in Medical History.” http://www.aaf-online.org/ Anderson v. W. R. Grace: Background/About the Case, Seattle University School of Law. http://www.law.seattleu.edu/centers-and-institutes/films-for-justice-institute/lessons-from- woburn/about-the-case Anderson, E. L. (1988). Behavioral Treatment of Autism. Documentary by Edward L. Anderson and Robert Aller. Focus International Andreas Ströhle et al. (2008.). Karl Bonhoeffer (1868–1948). American Journal of Psychiatry Andrews, J. (1997). The History of Bethlem. (pp. 272). New, York: Psychology Press Angres, R. (Oct. 1980). Who, Really, Was Bruno Bettelheim? Commentary Anthony, E. J. (1958). An Experimental Approach to the Psychopathology of Childhood Autism. -

NAS Richmond Info Pack December 2020

AUTISM: A SPECTRUM CONDITION AUTISM, ASPERGER’S SYNDROME AND SOCIAL COMMUNICATION DIFFICULTIES AN INFORMATION PACK A GUIDE TO RESOURCES, SERVICES AND SUPPORT FOR AUTISTIC PEOPLE OF ALL AGES; THEIR FAMILIES, FRIENDS, ASSOCIATES AND PROFESSIONALS Produced by the National Autistic Society’s Richmond Branch. Online edition December 2020 Introduction 1 Introduction AN INTRODUCTION: WHAT WE OFFER The Richmond Branch of The National Autistic Society is a friendly parent-led group aiming to support families and autistic people in the borough. We hold coffee mornings, liaise with other groups and provide regular updates through emails and our Branch website. We are also working with our local authority and other professionals to improve access to health, social services and educational provision. Our core objectives are: Awareness, Support, Information Our present activities: Awareness and liaison. Networking and partnering with other local organisations, sharing expertise and working with them to improve services. Raising awareness and representing families and individuals affected by autism by involvement in the local authority’s implementation of the Autism Strategy, SEND plus other autism interest/pan-disability rights groups. Family and individual support. This is offered primarily via email support, plus our coffee mornings. Information. We aim to help and inform families and autistic people, and do so via: • Our Branch website. This gives details of our Branch and NAS Head Office’s activities, other groups, general activities and events, plus the online Information Pack. • The NAS Richmond Branch Information Pack. An essential guide to autism services and support. Written by local parents, the Information Pack aims to help anyone affected by autism or Asperger syndrome, including parents, carers and anyone else who provides support.