Rachlin Dissertation Deposit Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of the Socialist Party. by J

Engdahl: The Death of the Socialist Party [Oct. 1924] 1 The Death of the Socialist Party. by J. Louis Engdahl Published in The Liberator, v. 7, no. 10, whole no. 78 (October 1924), pp. 11-14. This year, 1924, will be notable in American It was at that time that I had a talk with Berger, political history. It will record the rise and the fall of enjoying his first term as the lone Socialist Congress- political parties. There is no doubt that there will be a man. He pushed the Roosevelt wave gently aside, as if realignment of forces under the banners of the two it were unworthy of attention. old parties, Republican and Democratic. The Demo- “In order to live, a political party must have an cratic Party is being ground into dust in this year’s economic basis,” he said. “The Roosevelt Progressive presidential struggle. Wall Street, more than ever, sup- Party has no economic basis. It cannot live.” That ports the Republican Party as its own. Middle class settled Roosevelt in Berger’s usual brusque style. elements, with their bourgeois following in the labor It is the same Berger who this year follows movement, again fondly aspire to a third party, a so- unhesitatingly the LaFollette candidacy, the “Roose- called liberal or progressive party, under the leader- velt wave” of 1924. To be sure, the officialdom of or- ship of Senator LaFollette. This is all in the capitalist ganized labor is a little more solid in support of LaFol- camp. lette in 1924 than it was in crawling aboard the Bull For the first time, this year, the Communists are Moose bandwagon in 1912. -

Economics During the Lincoln Administration

4-15 Economics 1 of 4 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy ECONOMICS DURING THE LINCOLN ADMINISTRATION War Debt . Increased by about $2 million per day by 1862 . Secretary of the Treasury Chase originally sought to finance the war exclusively by borrowing money. The high costs forced him to include taxes in that plan as well. Loans covered about 65% of the war debt. With the help of Jay Cooke, a Philadelphia banker, Chase developed a war bond system that raised $3 billion and saw a quarter of middle class Northerners buying war bonds, setting the precedent that would be followed especially in World War II to finance the war. Morrill Tariff Act (1861) . Proposed by Senator Justin S. Morrill of Vermont to block imported goods . Supported by manufacturers, labor, and some commercial farmers . Brought in about $75 million per year (without the Confederate states, this was little more than had been brought in the 1850s) Revenue Act of 1861 . Restored certain excise tax . Levied a 3% tax on personal incomes higher than $800 per year . Income tax first collected in 1862 . First income tax in U. S. history The Legal Tender Act (1862) . Issued $150 million in treasury notes that came to be called greenbacks . Required that these greenbacks be accepted as legal tender for all debts, public and private (except for interest payments on federal bonds and customs duties) . Investors could buy bonds with greenbacks but acquire gold as interest United States Note (Greenback). EarthLink.net. 18 July 2008 <http://home.earthlink.net/~icepick119/page11.html> Revenue Act of 1862 Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School. -

Betting the Farm: the First Foreclosure Crisis

AUTUMN 2014 CT73SA CT73 c^= Lust Ekv/lll Lost Photographs _^^_^^ Betting the Farm: The First Foreclosure Crisis BOOK EXCERPr Experience it for yourself: gettoknowwisconsin.org ^M^^ Wisconsin Historic Sites and Museums Old World Wisconsin—Eagle Black Point Estate—Lake Geneva Circus World—Baraboo Pendarvis—Mineral Point Wade House—Greenbush !Stonefield— Cassville Wm Villa Louis—Prairie du Chien H. H. Bennett Studio—Wisconsin Dells WISCONSIN Madeline Island Museum—La Pointe First Capitol—Belmont HISTORICAL Wisconsin Historical Museum—Madison Reed School—Neillsville SOCIETY Remember —Society members receive discounted admission. WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Director, Wisconsin Historical Society Press Kathryn L. Borkowski Editor Jane M. de Broux Managing Editor Diane T. Drexler Research and Editorial Assistants Colleen Harryman, John Nondorf, Andrew White, John Zimm Design Barry Roal Carlsen, University Marketing THE WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY (ISSN 0043-6534), published quarterly, is a benefit of membership in the Wisconsin Historical Society. Full membership levels start at $45 for individuals and $65 for 2 Free Love in Victorian Wisconsin institutions. To join or for more information, visit our website at The Radical Life of Juliet Severance wisconsinhistory.org/membership or contact the Membership Office at 888-748-7479 or e-mail [email protected]. by Erikajanik The Wisconsin Magazine of History has been published quarterly since 1917 by the Wisconsin Historical Society. Copyright© 2014 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 16 "Give 'em Hell, Dan!" ISSN 0043-6534 (print) How Daniel Webster Hoan Changed ISSN 1943-7366 (online) Wisconsin Politics For permission to reuse text from the Wisconsin Magazine of by Michael E. -

ORAL HISTORY of CHARLES F. MURPHY Interviewed by Carter H

ORAL HISTORY OF CHARLES F. MURPHY Interviewed by Carter H. Manny Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 1995 Revised Edition © 2003 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available to the public for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iv Preface v Outline of Topics viii Oral History 1 Selected References 57 Curriculum Vitæ 59 Index of Names and Buildings 61 iii FOREWORD The Department of Architecture at The Art Institute of Chicago is pleased to include this document, an interview of Charles F. Murphy by Carter Manny, in our collection of oral histories of Chicago architects. Carter Manny, a close associate of Murphy's, deserves our lasting thanks for his perception in recognizing the historical significance of Murphy's so often casually told stories and for his efforts to given them permanent form. It is an important addition to our collection because it brings to light many aspects of the practice of architecture in Chicago in the early years that only a privileged few could address. We share Carter's regret that we could not have had more of Murphy's recollections, but are indeed appreciative for what is here. -

Download the First Chapter

Copyright © 2013 Jack O’Donnell All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photograph, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the express written permission of the author, except where permitted by law. ISBn 978-1-59715-096-5 Library of Congress Catalog Number 2005nnnnnn First Printing CONTENTS Foreword. .xiii PART ONE Chapter One: A Reformer Is Born. .3 Chapter Two: Empire State Politics and Tammany Hall. .9 Chapter Three: William Sulzer’s Political Beginnings . 15 Chapter Four: Onward to Congress . .23 Chapter Five: Mayor William Gaynor. 31 Chapter Six: The Campaign of 1910 . 37 Chapter Seven: The Election of 1912. 49 PART TWO Chapter Eight: Governor William Sulzer . 67 Chapter Nine: Legislative Program . .81 Chapter Ten: Reformer . 85 Chapter Eleven: The Commission on Inquiry. .93 Chapter Twelve: “Gaffney or War!” . 101 Chapter Thirteen: Jobs, Jobs, and More Jobs . 109 Chapter Fourteen: Direct Primaries . .113 Chapter Fifteen: The Scandals. 139 PART THREE Chapter Sixteen: The Frawley Committee. .147 Chapter Seventeen: The Sulzer Campaign Fund. 153 Chapter Eighteen: Impeachment. 161 Chapter Nineteen: The Fallout . 175 Chapter Twenty: Governor Glynn? . .185 PART FOUR Chapter Twenty-One: Court of Impeachment . .191 Chapter Twenty-Two: The Verdict . .229 Chapter Twenty-Three: Aftermath . .239 PART FIVE Chapter Twenty-Four: The Campaign of 1917. .251 Chapter Twenty-Five: A Ghost Before He Died . .259 Acknowledgments . 263 Notes . .265 Bibliography . 277 FOREWORD William Sulzer is remembered by history as a wronged man. He was a reformer destroyed by the corrupt system he was elected to challenge and that he tried to change. -

Taxes, Investment, and Capital Structure: a Study of U.S

Taxes, Investment, and Capital Structure: A Study of U.S. Firms in the Early 1900s Leonce Bargeron, David Denis, and Kenneth Lehn◊ August 2014 Abstract We analyze capital structure decisions of U.S. firms during 1905-1924, a period characterized by two relevant shocks: (i) the introduction of corporate and individual taxes, and (ii) the onset of World War I, which resulted in large, transitory increases in investment outlays by U.S. firms. Although we find little evidence that shocks to corporate and individual taxes have a meaningful influence on observed leverage ratios, we find strong evidence that changes in leverage are positively related to investment outlays and negatively related to operating cash flows. Moreover, the transitory investments made by firms during World War I are associated with transitory increases in debt, especially by firms with relatively low earnings. Our findings do not support models that emphasize taxes as a first-order determinant of leverage choices, but do provide support for models that link the dynamics of leverage with dynamics of investment opportunities. ◊ Leonce Bargeron is at the Gatton College of Business & Economics, University of Kentucky. David Denis, and Kenneth Lehn are at the Katz Graduate School of Business, University of Pittsburgh. We thank Steven Bank, Alex Butler, Harry DeAngelo, Philipp Immenkotter, Ambrus Kecskes, Michael Roberts, Jason Sturgess, Mark Walker, Toni Whited and seminar participants at the 2014 SFS Finance Cavalcade, the University of Alabama, University of Alberta, University of Arizona, Duquesne University, University of Kentucky, University of Pittsburgh, University of Tennessee, and York University for helpful comments. We also thank Peter Baschnegal, Arup Ganguly, and Tian Qiu for excellent research assistance. -

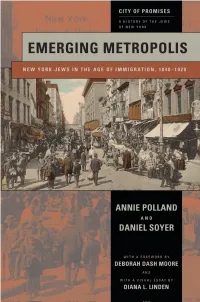

Emerging Metropolis

Emerging Metropolis New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840 – 1920 CITY OF PROMISES was made possible in part through the generosity of a number of individuals and foundations. Th eir thoughtful support will help ensure that this work is aff ordable to schools, libraries, and other not-for-profi t institutions. Th e Lucius N. Littauer Foundation made a leadership gift before a word of CITY OF PROMISES had been written, a gift that set this project on its way. Hugo Barreca, Th e Marian B. and Jacob K. Javits Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. Peter Malkin, David P. Solomon, and a donor who wishes to remain anonymous helped ensure that it never lost momentum. We are deeply grateful. CITY OF PROMISES A HISTORY OF THE JEWS OF NEW YORK GENERAL EDITOR: DEBORAH DASH MOORE Volume 1 Haven of Liberty New York Jews in the New World, 1654 – 1865 Howard b. Rock Volume 2 Emerging Metropolis New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840 – 1920 Annie Polland and Daniel Soyer Volume 3 Jews in Gotham New York Jews in a Changing City, 1920 – 2010 Jeffrey S. Gurock Advisory Board: Hasia Diner (New York University) Leo Hershkowitz (Queens College) Ira Katznelson (Columbia University) Th omas Kessner (CUNY Graduate Center) Tony Michels (University of Wisconsin, Madison) Judith C. Siegel (Center for Jewish History) Jenna Weissman-Joselit (Princeton University) Beth Wenger (University of Pennsylvania) CITY OF PROMISES A HISTORY OF THE JEWS OF NEW YORK EMERGING METROPOLIS NEW YORK JEWS IN THE AGE OF IMMIGRATION, 1840–1920 ANNIE POLLAND AND DANIEL SOYER WITH A FOREWORD BY DEBORAH DASH MOORE AND WITH A VISUAL ESSAY BY DIANA L. -

The Crime and Society Issue

FALL 2020 THE CRIME AND SOCIETY ISSUE Can Academics Such as Paul Butler and Patrick Sharkey Point Us to Better Communities? Michael O’Hear’s Symposium on Violent Crime and Recidivism Bringing Baseless Charges— Darryl Brown’s Counterintuitive Proposal for Progress ALSO INSIDE David Papke on Law and Literature A Blog Recipe Remembering Professor Kossow Princeton’s Professor Georgetown’s Professor 1 MARQUETTE LAWYER FALL 2020 Patrick Sharkey Paul Butler FROM THE DEAN Bringing the National Academy to Milwaukee—and Sending It Back Out On occasion, we have characterized the work of Renowned experts such as Professors Butler and Sharkey Marquette University Law School as bringing the world and the others whom we bring “here” do not claim to have to Milwaukee. We have not meant this as an altogether charted an altogether-clear (let alone easy) path to a better unique claim. For more than a century, local newspapers future for our communities, but we believe that their ideas have brought the daily world here, as have, for decades, and suggestions can advance the discussion in Milwaukee broadcast services and, most recently, the internet. And and elsewhere about finding that better future. many Milwaukee-based businesses, nonprofits, and So we continue to work at bringing the world here, organizations are world-class and world-engaged. even as we pursue other missions. To reverse the phrasing Yet Marquette Law School does some things in this and thereby to state another truth, we bring Wisconsin regard especially well. For example, in 2019 (pre-COVID to the world in issues of this magazine and elsewhere, being the point), about half of our first-year students had not least in the persons of those Marquette lawyers been permanent residents of other states before coming who practice throughout the United States and in many to Milwaukee for law school. -

Did Constitutions Matter During the American Civil War?

DID CONSTITUTIONS MATTER DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR? SUKRIT SABHLOK Monash University, Australia Abstract: The question of why the Confederate States of America lost the American Civil War has been extensively discussed, with scholars such as Frank Owsley and David Donald arguing that constitutional text and philosophy – and a preference for local over central government action – constrained the CSA’s options and therefore prospects for victory. While Owsley and Donald’s portrayal of a government hindered by constitutional fidelity has been countered by Richard Beringer, Herman Hattaway and William Still, who have pointed out that the Confederate government grew in size and scope during the war in spite of apparent legal restrictions, there has been limited examination of the factual basis underlying the thesis that constitutions functioned as a restraint. This paper addresses the US Constitution and the Confederate Constitutions (provisional and final) with special attention to how certain provisions and interpretive actions may have constrained the central government in the realm of economic policy. I find that both documents were not clearly relevant due to being inconsistently obeyed. The Confederacy disregarded provisions relating to fiscal, monetary and trade policy, even though it is likely that adhering to its Constitution in these areas could have strengthened its position and allowed it to supply its armies more adequately. It is likely that non-constitutional discretionary factors primarily account for the Confederacy’s defeat. I INTRODUCTION Now, our Constitution is new; it has gone through no perils to test and try its strength and capacity for the work it was intended to perform. -

Article Titles Subjects Date Volume Number Issue Number Leads State

Article Titles Subjects Date Volume Issue Number Number Leads State For Freedom Fred C. Tucker Jr., Ogden and Sheperd Elected Board of Trustees 1936 October 1 1 Trustees James M. Ogden (photo); Monument to Elrod: Citizens Alumni, Samuel H. Elrod Oct 1 1936 1 1 of Clark, S.D. Honor Memory (photo) of DePauw Alumnus DePauw Expedition Spends Biology Department 1936 October 1 1 Summer In Jungle: Many New Truman G. Yuncker Plant Specimens Brought Back (photo); to Campus From Central Ray Dawson (photo) Honduras Howard Youse (photo) Obituaries Obituaries 1936 October 1 1 Blanche Meiser Dirks Augustus O. Reubelt William E. Peck Joseph S. White Ella Zinn Henry H. Hornbrook Commodore B. Stanforth Allie Pollard Brewer William W. Mountain George P. Michl Harry B. Potter R. Morris Bridwell Mary Katheryn Vawter Professor Gough, Dean Alvord Faculty, Prof. Harry B. 1936 October 1 1 Retire Gough (photo), Katharine Sprague New President and Officers of H. Philip Maxwell 1936 October 1 1 Alumni Association (photo) Harvey B. Hartsock (photo) H. Foster Clippinger (photo) Lenore A. Briggs (photo) Opera Singer Ruth Rooney (photo) 1936 October 1 1 School of Music Alumni Opera Dr. Wildman New President: President, Clyde E. Oct 1 1936 1 1 DePauw Alumnus is Wildman (photo), Unanimous Choice of Board of Alumni Trustees Civilization By Osmosis - - Alumni; 1936 November 1 2 Ancient China Bishop, Carl Whiting (photo) Noteworthy Alumni Alumni, B.H.B. Grayston 1936 November 1 2 (photo), Mable Leigh Hunt (photo), Frances Cavanah (photo), James E. Watson (photo), Orville L. Davis (photo), Marshall Abrams (photo), Saihachi Nozaki (photo), Marie Adams (photo), James H. -

The Great Unwashed Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920

Washiîi! The Great Unwashed Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920 a\TH5 FOR Marilyn Thornton Williams Washing "The Great Unwashed" examines the almost forgotten public bath movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth cen turies—its origins, its leaders and their motives, and its achievements. Marilyn Williams surveys the development of the American obsession with cleanliness in the nineteenth century and discusses the pub lic bath movement in the context of urban reform in New York, Baltimore, Philadel phia, Chicago, and Boston. During the nineteenth century, personal cleanliness had become a necessity, not only for social acceptability and public health, but as a symbol of middle-class sta tus, good character, and membership in the civic community. American reformers believed that public baths were an impor tant amenity that progressive cities should provide for their poorer citizens. The bur geoning of urban slums of Irish immi grants, the water cure craze and other health reforms that associated cleanliness with health, the threat of epidemics—es pecially cholera—all contributed to the growing demand for public baths. New waves of southern and eastern European immigrants, who reformers perceived as unclean and therefore unhealthy, and in creasing acceptance of the germ theory of disease in the 1880s added new impetus to the movement. During the Progressive Era, these fac tors coalesced and the public bath move ment achieved its peak of success. Between 1890 and 1915 more than forty cities constructed systems of public baths. City WASHING "THE GREAT UNWASHED" URBAN LIFE AND URBAN LANDSCAPE SERIES Zane L. Miller and Henry D.