Profile at a Glance Central African Republic Markounda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa As of 26 September 2014

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa as of 26 September 2014 N'Djamena UNHCR Representation NIGERIA UNHCR Sub-Office Kerfi SUDAN UNHCR Field Office Bir Nahal Maroua UNHCR Field Unit CHAD Refugee Sites 18,000 Haraze Town/Village of interest Birao Instability area Moyo VAKAGA CAR refugees since 1 Dec 2013 Sarh Number of IDPs Moundou Doba Entry points Belom Ndele Dosseye Sam Ouandja Amboko Sido Maro Gondje Moyen Sido BAMINGUI- Goré Kabo Bitoye BANGORAN Bekoninga NANA- Yamba Markounda Batangafo HAUTE-KOTTO Borgop Bocaranga GRIBIZI Paoua OUHAM 487,580 Ngam CAMEROON OUHAM Nana Bakassa Kaga Bandoro Ngaoui SOUTH SUDAN Meiganga PENDÉ Gbatoua Ngodole Bouca OUAKA Bozoum Bossangoa Total population Garoua Boulai Bambari HAUT- Sibut of CAR refugees Bouar MBOMOU GadoNANA- Grimari Cameroon 236,685 Betare Oya Yaloké Bossembélé MBOMOU MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO Zemio Chad 95,326 Damara DR Congo 66,881 Carnot Boali BASSE- Bertoua Timangolo Gbiti MAMBÉRÉ- OMBELLA Congo 19,556 LOBAYE Bangui KOTTO KADÉÏ M'POKO Mbobayi Total 418,448 Batouri Lolo Kentzou Berbérati Boda Zongo Ango Mbilé Yaoundé Gamboula Mbaiki Mole Gbadolite Gari Gombo Inke Yakoma Mboti Yokadouma Boyabu Nola Batalimo 130,200 Libenge 62,580 IDPs Mboy in Bangui SANGHA- Enyelle 22,214 MBAÉRÉ Betou Creation date: 26 Sep 2014 Batanga Sources: UNCS, SIGCAF, UNHCR 9,664 Feedback: [email protected] Impfondo Filename: caf_reference_131216 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC The boundaries and names shown and the OF THE CONGO designations used on this map do not imply GABON official endorsement or acceptance by the United CONGO Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. -

CRISIS in the CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC in a Neglected Emergency, Children Need Aid, Protection – and a Future CRISIS in the CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC

© UNICEF/UN0239441/GILBERTSON VII PHOTO UNICEF CHILD ALERT November 2018 CRISIS IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC In a neglected emergency, children need aid, protection – and a future CRISIS IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC REPUBLIQUECentralN'D JCENTRAFRICAINE:A MAfricanENA RepublicCarte des mouvements de population – septembre 2018 SUDAN 2 221 CHAD 99 651 SOUTH VAKAGA SUDAN 1 526 1 968 BAMINGUI- BANGORAN 6 437 48 202 49 192 HAUTE-KOTTO NANA 44 526 GRÉBIZI 107 029 OUHAM- OUHAM PENDÉ 108 531 HAUT- 16 070 MBOMOU KÉMO OUAKA NANA 22 830 OMBELLA-MPOKO 53 336 MAMBÉRÉ 11 672 BASSE 17 425 KOTTO MBOMOU 14 406 BANGUI 45 614 MAMBÉRÉ- 7 758 KADEI 85 431 LOBAYE SANGHA Refugees CAMEROON MBAERE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Internally displaced people 2 857 31 688 173 136 OF THE CONGO Source: Commission de mouvement 264 578 de populations CONGO September 2018 Source: OCHA, UNHCR. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. UNICEF CHILD ALERT | November 2018 IN A NEGLECTED EMERGENCY, CHILDREN NEED AID, PROTECTION – AND A FUTURE 1 REPUBLIQUEN'D JCENTRAFRICAINE:AMENA Carte des mouvements de population – septembre 2018 SUDAN In this Child Alert 2 221 CHAD Overview: Resurgent conflict, plus poverty, equals danger for children .................................. 2 1. Children and families displaced 99 651 SOUTH VAKAGA and under attack .................................................. 7 SUDAN 2. Alarming malnutrition rates – 1 526 and the worst may be yet to come .................... 9 1 968 3. Education in emergencies: BAMINGUI- Learning under fire .............................................11 BANGORAN 4. Protecting children and young people 6 437 from lasting harm ...............................................13 48 202 49 192 HAUTE-KOTTO 5. -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Central African Republic: Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where? (05 May 2014)

Central African Republic: Who has a Sub-Office/Base where? (05 May 2014) LEGEND DRC IRC DRC Sub-office or base location Coopi MSF-E SCI MSF-E SUDAN DRC Solidarités ICRC ICDI United Nations Agency PU-AMI MENTOR CRCA TGH DRC LWF Red Cross and Red Crescent MSF-F MENTOR OCHA IMC Movement ICRC Birao CRCA UNHCR ICRC MSF-E CRCA International Non-Governmental OCHA UNICEF Organization (NGO) Sikikédé UNHCR CHAD WFP ACF IMC UNDSS UNDSS Tiringoulou CRS TGH WFP UNFPA ICRC Coopi MFS-H WHO Ouanda-Djallé MSF-H DRC IMC SFCG SOUTH FCA DRC Ndélé IMC SUDAN IRC Sam-Ouandja War Child MSF-F SOS VdE Ouadda Coopi Coopi CRCA Ngaounday IMC Markounda Kabo ICRC OCHA MSF-F UNHCR Paoua Batangafo Kaga-Bandoro Koui Boguila UNICEF Bocaranga TGH Coopi Mbrès Bria WFP Bouca SCI CRS INVISIBLE FAO Bossangoa MSF-H CHILDREN UNDSS Bozoum COHEB Grimari Bakouma SCI UNFPA Sibut Bambari Bouar SFCG Yaloké Mboki ACTED Bossembélé ICRC MSF-F ACF Obo Cordaid Alindao Zémio CRCA SCI Rafaï MSF-F Bangassou Carnot ACTED Cordaid Bangui* ALIMA ACTED Berbérati Boda Mobaye Coopi CRS Coopi DRC Bimbo EMERGENCY Ouango COHEB Mercy Corps Mercy Corps CRS FCA Mbaïki ACF Cordaid SCI SCI IMC Batalimo CRS Mercy Corps TGH MSF-H Nola COHEB Mercy Corps SFCG MSF-CH IMC SFCG COOPI SCI MSF-B ICRC SCI MSF-H ICRC ICDI CRS SCI CRCA ACF COOPI ICRC UNHCR IMC AHA WFP UNHCR AHA CRF UNDSS MSF-CH OIM UNDSS COHEB OCHA WFP FAO ACTED DEMOCRATIC WHO PU-AMI UNHCR UNDSS WHO CRF MSF-H MSF-B UNFPA REPUBLIC UNICEF UNICEF 50km *More than 50 humanitarian organizations work in the CAR with an office in Bangui. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

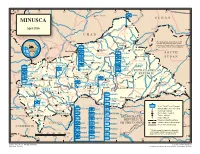

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Humanitarian Snapshot (As of 22 June 2015)

Central African Republic: Humanitarian Snapshot (as of 22 June 2015) The crisis in CAR has forced more than 1 million people to flee their homes. Today, more than 399,000 KEY FIGURES people remain displaced, living in the bush, in camps or with host families. They are among the 2.7 million MORE Central African who depend on aid to survive, including 1.2 million people food insecure. Although the 0.46 THAN 53% of the CAR overall political situation in the country has improved, continued insecurity due to banditry and sporadic inter million refugees reside in communal violence is hindering the ability of aid organizations to reach those in need of assistance and the Cameroon. redeployment of authorities and state basic services throughout the country. Neighbouring Cameroon, Chad, DRC and Congo still host more than 458,000 Central African refugees. 39% of the IDPs are SUDAN ONLY living in the sites in 0.39 Bangui and outside. CHAD million Birao The remaining IDPs are residing both host families and bush 92,504 refugees 1.2 OR 32% of the total million population of the CAR are food Ndélé SOUTH-SUDAN insecure (IPC, Apr 2015) 243,549 Markounda CURRENT HUMANITARIAN refugees Ngaoundaye Batangafo Kaga-Bandoro SITUATION Mbrès Koui Nana-Bakassa Bria Humanitarian needs in CAR continue to Bossangoa Bozoum Dékoa surpass available resources and Bambari humanitarian partners delivering live-saving Bouar CAMEROON Grimari assistance are reporting that operations are Yaloké Sibut shutting down due to lack of funding. Obo Bangassou Carnot Amada-Gaza While the raining season sets in across the Berbérati country, which enables the planting season Bangui Mobaye to commence, high pressure is applied by Mbaïki LEGEND herders on the meager agriculture zones IDPs in sites Nola following the diversion of transhumance 97,195 Transhumance passage corridors resulting from the tense refugees 30,000 - 35,000 area socio-politico situation. -

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic: Challenges and Priorities High-level dialogue on building support for key SSR priorities in the Central African Republic, 21-22 June 2016 Cover Photo: High-level dialogue on SSR in the CAR at the United Nations headquarters on 21 June 2016. Panellists in the center of the photograph from left to right: Adedeji Ebo, Chief, SSRU/OROLSI/DPKO; Jean Willybiro-Sako, Special Minister-Counsellor to the President of the Central African Republic for DDR/SSR and National Reconciliation; Miroslav Lajčák, Minister of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic; Joseph Yakété, Minister of Defence of Central African Republic; Mr. Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA. Photo: Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic The report was produced by the Security Sector Reform Unit, Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, United Nations. © United Nations Security Sector Reform Unit, 2016 Map of the Central African Republic 14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° AmAm Timan Timan The boundaries and names shown and the designations é oukal used on this map do not implay official endorsement or CENTRAL AFRICAN A acceptance by the United Nations. t a SUDAN lou REPUBLIC m u B a a l O h a r r S h Birao e a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 10 h r ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh k Garba Sarh Bahr Aou CENTRAL Ouanda AFRICAN Djallé REPUBLIC Doba BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Sam -

Central African Republic: Population Displacement January 2012

Central African Republic: Population Displacement January 2012 94,386 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in 5,652 the Central African Republic (CAR), where close SUDAN 24,951 65,364 Central to 21,500 were newly displaced in 2012 1,429 African refugees 71,601 returnees from within CAR or Birao neighboring countries 12,820 CHAD 6,880 6,516 Vakaga 19,867 refugees from Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo and 225 11,967 asylum-seekers of varying nationalities reside in Ouanda- the CAR and 152,861 Central African refugees 12,428 Djallé Ndélé are living in neighboring countries 3,827 543 Bamingui- 85,092 Central 7,500 Bangoran African refugees 8,736 1,500 2,525 Kabo 812 Ouadda 5,208 SOUTH SUDAN Markounda Bamingui Haute-Kotto Ngaoundaye 500 3,300 Batangafo Kaga- Haut- Paoua Bandoro Mbomou Nana- Nana-Gribizi Koui Boguila 20 6,736 Bria Bocaranga Ouham Ouham Ouaka 5,517 Djéma 1,033 Central 2,3181,964 5,615 African refugees 3,000 Pendé 3,287 2,074 1,507 128 Bossemtélé Kémo Bambari 1,226 Mbomou 800 Baboua Obo Zémio Ombella M'Poko 1,674 Rafaï Nana-Mambéré 5,564 Bakouma Bambouti CAMEROON 6,978 Basse- Bangassou Kotto Mambéré-Kadéï Bangui Lobaye Returnees Mongoumba Internally displaced persons (IDPs) 1,372 Central Refugees Sangha- African refugees Figures by sub-prefecture Mbaéré Returnee DEMOCRATIC movement REPUBLIC OF THE IDP camp IDP CONGO CONGO Refugee camp Refugee 0 50 100 km Sources: Various sources compiled by OCHA CAR Due to diculty in tracking spontaneous returns, breakdown of refugee returnees and IDP returnees is not available at the sub-prefectural level. -

Key Points Situation Overview

Central African Republic Situation Report No. 55 | 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC (CAR) Situation Report No. 55 (as of 27 May 2015) This report is produced by OCHA CAR in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period between 12 and 26 May 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 10 June 2015. Key Points On 13 May, the IASC deactivated the Level 3/L3 Response, initially declared in December 2013. The mechanism aimed at scaling up the systemic response through surged capacities and strengthened humanitarian leadership, resulting in a doubling of humanitarian actors operating in country. On 27 May, the Emergency Relief Coordinator, Valerie Amos, designated Aurelien Agbénonci, Deputy Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Resident Coordinator in the CAR, as Humanitarian Coordinator (HC). A Deputy HC will be also be nominated. An international conference on CAR humanitarian needs, recovery and resilience- building was held in Brussels on 26 May under the auspices of the European Union. Preliminary reports tally pledges for humanitarian response at around US$138 million, with the exact proportion of fresh pledges yet to be determined. 426,240 2.7million 79% People in need of Unmet funding More than 300 children were released from IDPs in CAR armed groups following a UNICEF-facilitated assistance requirements agreement by the groups’ leaders to free all children in their ranks. 36,930 4.6 million US$131 million in Bangui Population of CAR pledged against The return and reinsertion process for IDPs at requirements of the Bangui M’poko site continues. As of 22 May $613 million 1,173 of the 4,319 households residing at the site have been registered in the 5th district of Bangui and will receive a one-time cash payment and return package. -

CAR CMP Population Moveme

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION Election-related displacements in CAR Cluster Protec�on République Centrafricaine As of 30 April 2021 Chari Dababa Guéra KEY FIGURES Refugee camp Number of CAR IDPs Mukjar As Salam - SD Logone-et-Chari Abtouyour Aboudéia !? Entry point Baguirmi newly displaced Kimi� Mayo-Sava Tulus Gereida Interna�onal boundaries Number of CAR returns Rehaid Albirdi Mayo-Lemié Abu Jabrah 11,148 15,728 Administra�ve boundaries level 2 Barh-Signaka Bahr-Azoum Diamaré SUDAN Total number of IDPs Total number of Um Dafoug due to electoral crisis IDPs returned during Mayo-Danay during April April Mayo-Kani CHAD Mayo-Boneye Birao Bahr-Köh Mayo-Binder Mont Illi Moyo Al Radoum Lac Léré Kabbia Tandjile Est Lac Iro Tandjile Ouest Total number of IDPs ! Aweil North 175,529 displaced due to crisis Mayo-Dallah Mandoul Oriental Ouanda-Djalle Aweil West La Pendé Lac Wey Dodjé La Nya Raja Belom Ndele Mayo-Rey Barh-Sara Aweil Centre NEWLY DISPLACED PERSONS BY ZONE Gondje ?! Kouh Ouest Monts de Lam 3,727 8,087 Ouadda SOUTH SUDAN Sous- Dosseye 1,914 Kabo Bamingui Prefecture # IDPs CAMEROON ?! ! Markounda ! prefecture ?! Batangafo 5,168!31 Kaga-Bandoro ! 168 Yalinga Ouham Kabo 8,087 Ngaoundaye Nangha ! ! Wau Vina ?! ! Ouham Markounda 1,914 Paoua Boguila 229 Bocaranga Nana Mbres Ouham-Pendé Koui 406 Borgop Koui ?! Bakassa Bria Djema TOuham-Pendéotal Bocaranga 366 !406 !366 Bossangoa Bakala Ippy ! Mbéré Bozoum Bouca Others* Others* 375 ?! 281 Bouar Mala Total 11,148 Ngam Baboua Dekoa Tambura ?! ! Bossemtele 2,154 Bambari Gado 273 Sibut Grimari -

Central African Republic

Central African Republic 14 December 2013 Prepared by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team PERIOD: SUMMARY 1 January – 31 December 2014 Strategic objectives 100% 1. Provide integrated life-saving assistance to people in need as a result of the continuing political and security crisis, particularly IDPs and their 4.6 million host communities. total population 2. Reinforce the protection of civilians, including of their fundamental human rights, in particular as it relates to women and children. 48% of total population 3. Rebuild affected communities‘ resilience to withstand shocks and 2.2 million address inter-religious and inter-community conflicts. estimated number of people in Priority actions need of humanitarian aid Rapidly scale up humanitarian response capacity, including through 43% of total population enhanced security management and strengthened common services 2.0 million (logistics including United Nations Humanitarian Air Service, and telecoms). people targeted for humanitarian Based on improved monitoring and assessment, cover basic, life- aid in this plan saving needs (food, water, hygiene and sanitation / WASH, health, nutrition and shelter/non-food items) of internally displaced people and Key categories of people in their host communities and respond rapidly to any new emergencies. need: Ensure availability of basic drugs and supplies at all clinics and internally 533,000 hospitals and rehabilitate those that have been destroyed or looted. 0.6 displaced Rapidly increase vaccine coverage, now insufficient, and ensure adequate million management of all cases of severe acute malnutrition. displaced 20,336 refugees Strengthen protection activities and the protection monitoring system 1.6 and facilitate engagement of community organizations in conflict resolution million and community reconciliation initiatives.