Walk Cycle Waterloo Region ATMP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waterloo's Culture Plan: a Catalyst for Culture 2014-2024

Waterloo’s Culture Plan: A Catalyst for Culture 2014-2024 Final Report Waterloo Culture Plan: A Catalyst for Culture 2014-2024 Final Report “It is obvious that people really care about Waterloo's future but with a view that things need some courage and innovation; an environment where creativity can be unleashed.” – Local resident 1 Waterloo Culture Plan: A Catalyst for Culture 2014-2024 Final Report Acknowledgements Waterloo's culture plan is the result of two years of research and consultation involving many individuals and groups within the city. Residents and stakeholders have helped to shape the vi- sion, guiding principles, goals and recommendations contained in this plan. The economic development and community services departments, on behalf of the City of Wa- terloo, are thankful for the time, effort and dedication of all that have contributed to this initiative. The community members who participated at the culture plan summit, in focus groups, at work- shops, via the discussion guide in person or online, or contributed to the project by sharing their talent in many other ways big and small have shaped a culture plan that will enrich the quality of life for Waterloo’s residents and delight visitors to the region. Thank you to staff across the cor- poration who shared information and ideas. The City of Waterloo would like to acknowledge Mayor Brenda Halloran and councillors Melissa Durrell, Diane Freeman, Jeff Henry, Karen Scian, Angela Vieth, Mark Whaley and Scott Witmer for their ongoing leadership and support for this project. Their involvement has been crucial to achieving this milestone in transforming Waterloo's cultural landscape. -

The Cord Weekly 2 > WEDNESDAY MARCH 1 2006 News

The CordThe tie that binds since 1926 Weekly HEADING DOWN THE HOMESTRETCH 101 The school year's winding down and we're guessing you probably haven't made the most of it. Thusly, Cord Features gives you a goal-oriented guide to the top 101 things you should do before you leave Waterloo this year, or for good ... FEATURE, 12-13 Volume 46 Issue 24 WEDNESDAY MARCH 1,2006 www.cordweekly.com Laurier sweeps to OUA gold medal WLU rink curls to a comfortable 7-4 win over Queen's MIKE BROWN four ends to the Golden Gaels in Sports Editor the final game of the round robin, a bye to the final hanging in the While the majority of students balance. were jet setting to tropical locales, The entire team, rounded out by drinking themselves into a stupor third-year lead David Jenkins, or - heaven forbid - reading, a rookie second Paul Arkilander and quartet of determined Laurier third-year vice Jeff Bennett, men with brooms were all busi- retained their composure and ness at the OUA Curling simply chipped away to secure a Championships in St. Catharine's 6-3 win. over the weekend. Combined with their stellar Led by third-year skip Bill start to the final - also against Francis, the men's rink showcased Queen's after they downed the their skill en route to a fairly stress- host Brock Badgers in the semi- free 7-4 win over Queen's in final - Francis and co. shut their Sunday's gold medal game, Kingston counterparts off the enough to secure Laurier's third scoreboard for ten straight ends. -

REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES Wednesday, September 27, 2006

REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES Wednesday, September 27, 2006 The following are the minutes of the Regular Council meeting held at 7:10 p.m. in the Regional Council Chamber, 150 Frederick Street, Kitchener, Ontario, with the following members present: Chair K. Seiling, J. Brewer, M. Connolly, D. Craig, K. Denouden, H. Epp, T. Galloway, J. Haalboom, R. Kelterborn, C. Millar, J. Mitchell, W. Roth, J. Smola*, B. Strauss, J. Wideman*, and C. Zehr. DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT None declared. CLOSED SESSION MOVED by K. Denouden SECONDED by M. Connolly That a closed meeting of Council be held on Wednesday, September 27, 2006 at 6:45 p.m. in accordance with Section 239 of the Municipal Act, 2001, for the purposes of considering the following subject matters: a) a proposed or pending acquisition of land b) personal matters about an identifiable individual CARRIED MOVED by B. Strauss SECONDED by W. Roth The Council reconvene in Open Session. CARRIED MOVED by B. Strauss SECONDED by J. Haalboom That Council change the start time of the October 11, 2006 Council meeting to 3:00 p.m. CARRIED Council - 2 - 06/09/27 DELEGATIONS a) Waterloo West Side Development i) Memo: Update on Wilmot Line Road Environmental Assessment and Associated Proposed Plans of Subdivision Chair Seiling summarized the memo from staff advising a final decision will not be made by the Commissioner until all of the reviews are completed, including the road Environmental Assessment. Staff will continue with the technical review. *J. Smola entered the meeting at 7:15 p.m. -

Rapid Transit Initiative

Rapid Transit Initiative Phase 2 Summary Report – Environmental Assessment Study September 24, 2009 in association with Region of Waterloo Rapid Transit Initiative Phase 2 Summary Report – Environmental Assessment Study September 24, 2009 Document Control Version History Version Date Change 0.1-Draft May 8, 2009 Preliminary Draft 1.0 September 24, 2009 Final Revision and Approval Control of Last Version Task Responsibility Position Date Preparation Doug Willoughby AECOM September 24, 2009 Project Manager Katie Harvey AECOM Designer - Transportation Revision Darshpreet Singh Region of Waterloo July 14, 2009 Bhatti Senior Project Manager Rapid Transit Initiative David Durant Region of Waterloo Senior Project Manager Rapid Transit Initiative Approval in association with Page i Region of Waterloo Rapid Transit Initiative Phase 2 Summary Report – Environmental Assessment Study September 24, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6.2.5. OTTAWA STREET (CHARLES STREET EAST TO MILL STREET) .................................................. 83 6.2.6. CNR HURON PARK SUBDIVISION (OTTAWA STREET SOUTH TO HAYWARD AVENUE) ........... 83 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 6.2.7. COURTLAND AVENUE ....................................................................................................................... 83 1.1. ONTARIO ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS FOLLOWED .................................................... 1 6.2.8. HYDRO CORRIDOR -

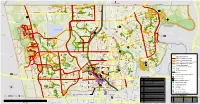

Waterloo Cycle

BENJAMIN RD ! ! St.Jacobs / Elmira ! KRESSLER RD TOWNSHIP RD 35 ! BURNING BUSH RD GLASGOW ST S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! UNIVERSITY AVE E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BENJAMIN RD ! ! BISCH ST ! ! MCMURRAY RD COUNTRY SQUIRE RD ! WESTMOUNT RD N ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! CHARING CX ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BRIDGE ST W ! ! ! ! ! ! KATHERINE ST S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! SANDBANKS CRES ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! CONSERVATION! MEADOWS DISTRICT ! ! RANKIN ST ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RIDEAU RIVER ST ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! COLDSTREAM DR ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ú ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! PINERY TRAIL ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! OSPREY DR ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! LK LOUISE ! BLVD ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! WATERTON DR ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ú ! ! ! ! ! -

The Grand River, Ontario

TThhee GGrraanndd RRiivveerr,, OOnnttaarriioo A Decade in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System: A Review of The Grand Strategy 1994-2004 Prepared for the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board by Barbara J. Veale Co-ordinated by Grand River Conservation Authority on behalf of the Province of Ontario Cambridge, Ontario May 2004 Copies available from: Grand River Conservation Authority 400 Clyde Road P.O. Box 729 Cambridge, Ontario N1R 5W6 Telephone: (519) 621-2761 Fax: (519) 621-4844 Website: www.grandriver.ca © Grand River Conservation Authority, 2004 ISBN 1-894414-07-1 (front) Wellington County Museum and Archives National Historic Site, Township of Centre Wellington (Photo Credit: Grand River Conservation Authority) West Montrose Covered Bridge, Township of Woolwich (Photo Credit: Elizabeth Bourque) Canoeing the Grand River (Photo Credit: Don Thomas) Caledonia Bow String Bridge, Haldimand County (Batik by Linda Risacher Copp; Photo Credit: Paul Kelly) Dunnville Marshes, Haldimand County (Photo Credit: Elizabeth Bourque) ii The Grand River, Ontario A Decade in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System: A Review of The Grand Strategy Prepared for the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board by Barbara J. Veale Coordinated by Grand River Conservation Authority on behalf of the Province of Ontario May 2004 Our Heritage Grand River Congratulations! On what you’ve attained, No one more deserved, than you my lady. So regal and picturesque and self-contained. From beginning to end, you capture many, Your flow, your roar, always unchained. Past hamlets, villages, towns and cities. Congratulations! On your new title in life. It can only get better, it’s true. No more jokes, like cut it with a knife. -

Region of Waterloo Biosolids Master Plan Appendix J to P

-·- • I,~ APPENDIX J: Notices & Communication Appendix J • Newspaper Notices: Guide Guide Content o Stage 1 o Stage 2 o Stage 3 o Stage 4 o Stage 5 o Stage 6 • Agency Contact List • Mail-out Letters • E-Newsletter and Biosolids Bulletin o Stage 1: . E-Newsletter #1 . E-Newsletter #2 . Biosolids Bulletin #1 . E-Newsletter #3 . Biosolids Bulletin #2 o Stage 2: . E-Newsletter #4 . Biosolids Bulletin #3 . E-Newsletter #5 . Biosolids Bulletin #4 . E-Newsletter #6 . Biosolids Bulletin #5 o Stage 3: . E-Newsletter #7, . Biosolids Bulletin #6 o Stage 4: . E-Newsletter #8, . Biosolids Bulletin #7 o Stage 5: . E-Newsletter #9, . Biosolids Bulletin #8 o Stage 6: . E-Newsletter #10 . Biosolids Bulletin #9 STAGE 1 Newspaper Notice BIOSOLIDS • Strategy .,..., 01 w.-. LAUNCH EVENT The Region of Waterloo Presents The Science of Biosolids What is it? What do we do with it? Join us on November 17th, 2015 along Biosolids Strategy Open House with Canada’s best known science th journalist, Bob McDonald, as we Tuesday, November 17 discuss the science of biosolids and 6:00-9:00pm how you can get involved in developing Waterloo Region Museum a new strategy for our community. 10 Huron Road, Kitchener ON The open house is free to attend, Bob McDonald Talk: 7:00pm but seating is limited for the talk with Bob McDonald, so Preregistration required for the please register in advance. discussion with Bob McDonald. If you have any questions or Registration opens November 4th comments please contact: Register at: Kaoru Yajima www.regionofwaterloo.ca/biosolids Tel 519-575-4757 ext. -

GSR Vertical File Index General Subjects

GSR Vertical File Index General Subjects Compiled by the staff of Information Services, Kitchener Public Library Revised 1 January 2017 - 1 - GSR General Subjects Abbreviations: CB-KW = Collective Biography – Kitchener Waterloo CB–Watco = Collective Biography – Waterloo County (Region) – excluding Kitchener –Waterloo RMW = Regional Municipality of Waterloo Note: Coverage starts from various dates to 31 December 2004. For articles from the Waterloo Region Record (formerly K-W Record), dated 1 January 2005 to the present, please see staff at the Information Level 2 desk (outside the Grace Schmidt Room). Thank you. Updated 1 January 2017 Page 2 of 638 GSR General Subjects GSR General Subject Headings Index General A AASMAN, SUSAN see CB WATCO ABATE, LAURA ABBAS, ALI see IRAQ – WAR 2003 ABBEY, JOHN see CB WATCO ABBOTT, BRUCE see CB KW ABBOTT, KATHLEEN (WIFE OF WILLIAM) NEE LOTH see CB KW ABERNATHY, RUTH see ARTISTS-RMW ABERLE, MURRAY see CB WATCO ABERLE, ROY see CB WATCO ABILITY CENTRE ABORIGINAL PEOPLES – ARCHAEOLOGY see also ARCHAEOLOGY ABORIGINAL PEOPLES – GENERAL ABORIGINAL PEOPLES – MISSISSAUGAS OF THE NEW CREDIT FIRST NATION ABORIGINAL PEOPLES – POWWOWS ABORIGINAL PEOPLES – SIX NATIONS OF THE GRAND RIVER ABORIGINAL PEOPLES – WEEJEENDIMIN NATIVE RESOURCE CENTRE ABORTION - K-W see also PLANNED PARENTHOOD - WATERLOO REGION; K-W RIGHT TO LIFE ABWUNZA YMCA CHILD CARE CENTRE see DAY CARE (A-Z) ACADEMY OF DANCE see BUS ENT WAT ACCIDENTS - KITCHENER, ONTARIO - 1995 - 1999, 2000 - see also scrapbooks in GSR (MGSR 363.100971345 ACCID for (Volume -

Parkland Strategy Development

City of Waterloo Parkland Strategy DRAFT Research, Analysis & Visioning Report June 2019 In association with: Monteith Brown Planning Consultants Domis Consulting Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of this Report 1 1.2 Waterloo Parkland Highlights 2 1.3 Benefits of Parks and Open Space 2 2 EXISTING POLICIES & PRACTICES...................................................................................... 12 2.1 Background Planning Documents 12 2.2 Asset Management & Park Improvements 23 3 COMMUNITY PROFILE ..................................................................................................... 25 3.1 Overview 25 3.2 Current and Forecasted Populations 26 3.3 Nodes and Corridors 27 3.4 Demographics 29 3.5 What This Means for Parkland 31 4 PARKLAND AND OPEN SPACE .......................................................................................... 32 4.1 Trends & Emerging Needs 32 4.2 Evaluation of Existing Policies & Practices 44 4.3 Inventory & Evaluation of Supply 52 4.4 Issues, Opportunities & Constraints 62 5 PARK AMENITIES ............................................................................................................. 73 5.1 General 75 5.2 Playgrounds 77 5.3 Splash Pads 80 5.4 Dog parks 83 5.5 Outdoor Skating Rinks 86 5.6 Tennis Courts 89 5.7 Pickleball Courts 91 5.8 Basketball Courts 93 5.9 Community Hubs (Gathering & Event Spaces) 97 5.10 Community Gardens 100 5.11 Other Amenities -

Stage 2 ION Public Consultation Centre Number 4

STAGE 2 ION: LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT KITCHENER TO CAMBRIDGE PUBLIC CONSULTATION CENTRE NO. 4 SUMMARY REPORT MAY 8, 9 AND 10, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................... 1 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 4 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................ 4 1.2 Transit Project Assessment Process Consultation Requirements ........................................ 4 2 CONSULTATION PROCESS .................................... 5 2.1 Purpose ...................................................................... 5 2.2 Consultation Method .................................................. 6 2.3 Outreach and Notification ........................................... 7 2.4 Participation................................................................ 9 3 FEEDBACK AND INPUT ......................................... 10 3.1 Positive Feedback .................................................... 10 3.2 Issues and Concerns ................................................ 12 4 NEXT STEPS ........................................................... 22 APPENDICES A NOTIFICATION MATERIAL B COMMENT SHEETS AND EMAIL SUBMISSIONS C ONLINE SURVEY Executive Summary Public Consultation Centre No. 4 (PCC No. 4) for the Stage 2 ION LRT project was held in May 2018. Hosted by the Region of Waterloo’s Rapid Transit team, these public consultation centres were held on three dates in different venues located across the study area: » May 8, 2018 – Holiday Inn Kitchener, -

Grand River Transit Northfield Drive Facility – Municipal Class Environmental Assessment, Schedule ‘C’ and Preliminary Design

Environmental Study Report Grand River Transit Northfield Drive Facility – Municipal Class Environmental Assessment, Schedule ‘C’ and Preliminary Design Prepared for Region of Waterloo by IBI Group March 9, 2017 IBI GROUP ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT GRAND RIVER TRANSIT NORTHFIELD DRIVE FACILITY – MUNICIPAL CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT, SCHEDULE ‘C’ AND PRELIMINARY DESIGN Prepared for Region of Waterloo Document Control Page CLIENT: Region of Waterloo Grand River Transit Northfield Drive Municipal Class Environmental PROJECT NAME: Assessment, Schedule 'C' and Preliminary Design Grand River Transit Northfield Drive Facility – Municipal Class REPORT TITLE: Environmental Assessment, Schedule ‘C’ and Preliminary Design IBI REFERENCE: 24RX14.0430 VERSION: DIGITAL MASTER: [File Location] ORIGINATOR: Marianne Alden-Radue REVIEWER: Don Drackley AUTHORIZATION: Eric Czerniak CIRCULATION LIST: Version 1 – December 2016 Version 2 – January 2017 HISTORY: Version 3,4 – February 2017 Version 5 – March 9, 2017 IBI GROUP ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT GRAND RIVER TRANSIT NORTHFIELD DRIVE FACILITY – MUNICIPAL CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT, SCHEDULE ‘C’ AND PRELIMINARY DESIGN Prepared for Region of Waterloo Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. i 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Study Purpose ........................................................................................................ -

MEDIA RELEASE: Immediate

MEDIA RELEASE: Immediate REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY OF WATERLOO CONSOLIDATED COUNCIL AGENDA Wednesday, June 12, 2002 Closed Session 6:30 p.m. Regular Meeting 7:00 p.m. REGIONAL COUNCIL CHAMBER 150 Frederick Street, Kitchener, ON * DENOTES CHANGES TO, OR ITEMS NOT PART OF ORIGINAL AGENDA 1. MOMENT OF SILENCE 2. ROLL CALL 3. MOTION TO GO INTO CLOSED SESSION (if necessary) 4. MOTION TO RECONVENE IN OPEN SESSION (if necessary) 5. DECLARATION OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT 6. PRESENTATIONS a) Mr. Randy Ellis, CEO and Mr. Mike O'Neal, Project Manager, Canada's Technology Triangle re: Connect Ontario Funding Application. 7. PETITIONS 8. DELEGATIONS a) Mr. Edward de Gale, Executive Director, Share the Warmth re: Deeper understanding of the Share the Warmth Program and its impact on low-income families in Waterloo Region. b) Mr. Bob McMullen, Chair, and Mr. Don Pavey, Cambridge Trails Advisory Committee re: 401 Townline Road Bridge Project. * c) Cambridge Area Transit Service Review. Refer Item 3 of PW-020604/S i) Sandy Kempel, Resident of Rosslinn Road, Cambridge ii) Peter Lard, Resident of Rosslinn Road, Cambridge iii) Mary Beth Racine, Resident of Rosslinn Road, Cambridge 9. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETINGS a) Council - May 22, 2002 b) Special Council Meeting - May 29, 2002 c) Planning & Works - June 4, 2002 d) Community Services - June 4, 2002 10. COMMUNICATIONS a) Association of Municipalities of Ontario re: i) Walkerton Inquiry Report Does Not Call For Radical Reform. Received for information. (P1 & P2) ii) Province Releases New Policy On "Spouse in the House". Received for information.