For the Curator of Trees and Teacups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection Finding Aid Collection Overview Title: The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012 (bulk 1808-1896) Creator: Osterweis, Rollin G. (Rollin Gustav), 1907- Extent : 159 volumes; 1 linear foot of archival material Repository: Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives Abstract: This collection holds 159 volumes that make up the Rollin G. Osterweis Collection of Irving Editions and Irvingiana. It also contains one linear foot of archival materials related to the collection. Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Item title. (date) City: Publisher [if applicable]. The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012, (Date of Access). Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives. Historic Hudson Valley. Provenance: This collection was created by Rollin Gustav Osterweis and donated to Historic Hudson Valley by Ruth Osterweis Selig. 18 December 2012. Access: This collection is open for research with some restrictions based on the fragility of certain materials. Research restrictions for individual items are available on request. For more information contact the Historic Hudson Valley librarian, Catalina Hannan: [email protected]. Copyright: Copyright of materials belongs to Historic Hudson Valley. Permission to reprint materials must be obtained from Historic Hudson Valley. The collection contains some material copyrighted by other organizations and individuals. It is the responsibility of the researcher to obtain all permission(s) related to the reprinting or copying of materials. Processed by: Christina Neckles Kasman, February-August 2013 Osterweis Irving Collection - 1 Biographical Note Rollin Gustav Osterweis was a native of New Haven, Connecticut, where his grandfather had established a cigar factory in 1860. -

The Rockefellers an Enduring Legacy

The Rockefellers An Enduring Legacy 90 / OCTOBER 2012 / WWW.WESTCHESTERMAGAZINE.COM alfway through a three-hour tour The views from Kykuit were astound- of the Kykuit mansion, the for- ing—possibly the best in Westchester. The mer home to four generations Hudson sparkled like a thousand stars lit up of Rockefellers, it became appar- in the night sky. Surrounding towns, includ- ent that I was going to need to ing Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow, looked as Huse the bathroom—a large mug of iced coffee if civilization had yet to move in, the tree- purchased at a Tarrytown café was to blame. tops hiding any sign of human life. I felt like My guide, Corinne, a woman of perhaps 94, a time-traveler whisked back to a bygone era. Look around eagerly led me to a marble bathroom enclosed This must have been the view that had in- by velvet ropes, telling me this may have been spired John D. Rockefeller to purchase land you. How where John D. Rockefeller had spent a great in Westchester in 1893. New York City, where deal of his time. When, after several high- the majority of the Rockefeller family resided, much of decibel explanations, she gathered the nature was just 31 miles away and a horse-drawn car- of my request, I was ushered away from the riage could make the journey to the estate in the land, tour by two elderly women carrying walkie- less than two hours. It was the perfect family talkies, taken down a long flight of wooden retreat, a temporary escape from city life. -

6 Stops in Washington Irving's Sleepy Hollow

Built in 1913, Kykuit was the home of oil tycoon 6 STOPS IN WASHINGTON John D. Rockefeller. Depending on which Kykuit tour you choose, you’ll want to set aside 1.5 to 3 hours IRVING’S SLEEPY HOLLOW (includes a shuttle bus to the location). Book on the Historic Hudson Valley website. • Philipsburg Manor • Sculpture of the Headless Horseman Sculpture of the Headless Horseman • The Headless Horseman Bridge 362 Broadway, Sleepy Hollow, New York • The Old Dutch Church and Burying Ground After purchasing the guidebook Tales of The Old • Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Dutch Burying Ground from Philipsburg Manor, walk • Sunnyside towards the Old Dutch Burying Ground. There are _______________________ several photo opportunities along the way. Approximately 300 feet (100 metres) up the road Notes you’ll find the sculpture of the Headless Horseman. Double-check opening times before you travel to Sleepy Hollow. At the time of writing, locations like Sunnyside and This sculpture was created for those visiting Sleepy Philipsburg Manor are open Wednesday to Sunday, May to Hollow to help us explore and relive the town’s rich early November. heritage, keeping the legend alive. Looking for public restrooms along the way? Plan for stops at Philipsburg Manor,Tarrytown station and Sunnyside. The Headless Horseman Bridge _______________________ “Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road Take the CROTON-HARMON STATION bound Metro- that led to it, and the bridge itself, were thickly shaded by North Train from Grand Central Terminal and get off overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it, even in the daytime; but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. -

Promise of Pocantico

- Prepared by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation , Partnerships Greenrock Complex Orangerie and Greenhouses Conference Center and Coach Barn Kykuit and Stewardship The Playhouse Breuer House and Guest Houses The Parkland : Redevelopment and Reprogramming of Use Patterns The Greenrock Village: Office and Shop Buildings The Commons: Orangerie, Greenhouses, and Coach Barn The Extended Campus: The Playhouse, Breuer House, and Guest Houses Future Expansion Creating Connections Evolution of the Landscape Conceptual Plan Rockefeller Brothers Fund Philanthropy for an Interdependent World Lake Road Tarrytown, New York .. www.rbf.org Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC .. www.nthp.org © Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Inc. All rights reserved. Ben Asen Mary Louise Pierson RBF Staff : . The Pocantico Center represents another remarkable Rockefeller resource, one directed to ever- greater public benefit and managed through a thoughtful, principled process entirely consistent with family traditions and philanthropy. In the Pocantico Committee of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund was charged with developing a long-range plan for the Center that is economically feasible and responsive to the surrounding community, and provides an enriching experience for a range of visitors. This report presents the plan that was approved by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund board on June , as a guide for future activity together with its partner, the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Over the past two years, the Committee drew upon many experts and professionals in relevant areas, conducted assessments of outside operations, and held meetings full of concentrated debate, examination, and discovery. The final product is a comprehensive document aligning statements of Mission, Vision, and Principles with insightful program initiatives and responsible financial considerations, all based upon the significant history and assets of Pocantico. -

French Sculpture Census / Répertoire De Sculpture Française

FRENCH SCULPTURE CENSUS / RÉPERTOIRE DE SCULPTURE FRANÇAISE MAILLOL, Aristide Banyuls-sur-Mer, Pyrénées-Orientales 1861 - Banyuls-sur- Mer, Pyrénées-Orientales 1944 Baigneuse se coiffant Bather Putting Up her Hair 1898 bronze statue Acc. No.: Credit Line: Kykuit, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Nelson A. Rockefeller bequest Photo credit: ph. gardenia.net © Artist : Sleepy Hollow, New York, Kykuit, John D. Rockefeller Estate www.hudsonvalley.org/historic-sites/kykuit Comment International Sculpture Center website, Kykuit gardens, August 18, 2015: Kykuit, completed in 1913 for John D. Rockefeller and home to four generations of the Rockefeller family, sits high above the eastern banks of the Hudson River over looking the Palisades. Within the gardens of Kykuit are two distinct collections of sculpture. The fountains, wellheads and classical figures - from ancient and Renaissance models or by American sculptors of the early 20th century - were assembled between 1906 and 1913 by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and landscape architect William Welles Bosworth. The terraces descending to the west and the formal geometric spaces defined by stone walls and box hedges are punctuated by the pergolas and fountains integral to Italian garden design. In 1963, Governor Nelson Rockefeller elaborated upon this tradition and brought to Kykuit works by Lachaise, Arp, Lipchitz, Marini and Giacometti, beginning the collection of modern sculpture that graces the park today. He continued to add pieces during his 16-year residence at Kykuit, taking great care in the precise siting of each. International in scope, this collection numbers more than 70 sculptures, and reflects many of the major trends of modern sculpture during the first three- quarters of the 20th-Century, including works by Maillol, Calder, Moore, Picasso, Noguchi, Meadmore, and Nadleman, among others. -

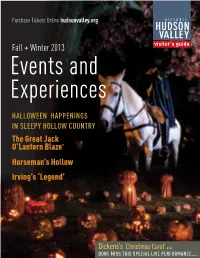

Fall + Winter 2013 Visitor's Guide Events and Experiences

Purchase Tickets Online hudsonvalley.org Fall + Winter 2013 visitor's guide Events and Experiences HALLOWEEN HAPPENINGS IN SLEEPY HOLLOW COUNTRY The Great Jack O’Lantern Blaze® Horseman’s Hollow Irving’s ‘Legend’ Dickens’s ‘Christmas Carol’ p.6A DONT MISS THIS SPECIAL LIVE PERFORMANCE.... 2A 3A SPECIAL EVENTS EVENTS SPECIAL SPOOKY AND SPECTACULAR FOR AGES 10+ Special Events FALL/WIN SEPTEMBER -DECEMBER 2013 ‘Best haunted house ever’ Historic Hudson Valley’s all-ages, TE family friendly special events ‘What an amazing experience… 2013 R draw tens of thousands of visitors so much fun and scare value’ each year. There is something ‘Makes me proud to live in Sleepy Hollow!’ here for everyone! October 5-6, 11-13, 18-20, 25-27 + November 1-2 —Facebook posts from Horseman’s Hollow visitors Irving's 'Legend' pg 2A Fridays: 6:15, 7:30, + 8:45pm Saturdays and Sundays: 5, 6:15, + 7:30pm The Legend Behind the 'Legend' pg 2A Irving’s ‘Legend’at Old Dutch Church Horseman's Hollow pg 3A SPELLBINDING foR AGES 10+ Accompanied by musician Jim Keyes, master storyteller Jonathan ® The Great Jack O’Lantern Blaze pg 4-5A Kruk — showcased on CBS Sunday Morning last year — offers a dramatic, spellbinding performance of Washington Irving’s classic tale, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Dickens's 'Christmas Carol' pg 6A ADVANCE TICKETS Adults, $16; Children under 18, $12 A Holiday Open House pg 6A ARE REQUIRED Members: $5 discount per ticket TICKets Oct 5-6, 11-13, 18-20, 25-27 + Nov 1-2 First admission at 7pm, last admission at 9:30pm (9pm Sundays) Many events SELL OUT and have limited capacity. -

Here We Are on the 200Th Anniversary of His Classic Story, Celebrating His Legacy of Artistic Inspiration and Achievement at the Nexus of the Tale Itself

WELCOME 1ST ANNUAL SLEEPY HOLLOW INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Could Washington Irving have predicted the enduring impact “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” would have on the world when it was published in 1819? Perhaps not. And yet here we are on the 200th anniversary of his classic story, celebrating his legacy of artistic inspiration and achievement at the nexus of the tale itself. The Sleepy Hollow International Film Festival is a celebration of cinematic and literary-themed wonders—a one-of-a-kind combination of film premieres, exclusive screenings, live events, scripts in competition as well as special guests, panels and much more, all taking place in the historic Hudson Valley during its magical, and wildly popular, Halloween season. All of us with SHIFF are thrilled to welcome you to be part of history with this first-ever large-scale genre film festival in Westchester County, NY, in one of the most famous locations in the entire world. We extend a special thanks to the fine folk, governments and associations of Sleepy Hollow and Tarrytown, the wondrous Tarrytown Music Hall and Warner Library, who proudly keep the spirit of Irving alive each and every day. So, for the next four days, revel in the inception of a new legend here in the Hollow. Enjoy, and let the bewitching begin! —The SHIFF Team Co-Founder/Director, Business Affairs DAVE NORRIS Advisory Board Lead Programmer DAN McKEON CHRIS POGGIALI FREDERICK K. KELLER TAYLOR WHITE Screenplay Board CHRIS TOWNSEND HARRY MANFREDINI Co-Founder/Director, DON LAMOREAUX Tech/Prints STEVE MITCHELL Programmer STEVE MITCHELL ZACH TOW CYRUS VORIS MATT VERBOYS CYRUS VORIS Official Photographer LARRY COHEN (In Memoriam. -

South End Historic District

HISTORIC AND NATURAL DISTRICTS FOR OFFICE USE ONLY INVENTORY FORM UNIQUE SITE NO. DIVISION FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION QUAD NEW YORK STATE PARKS AND RECREATION SERIES ALBANY, NEW YORK (518) 474-0479 NEG. NO. February 2010; Revised YOUR NAME: Allison S. Rachleff DATE: 2011 AECOM YOUR ADDRESS: One World Financial Center, 25th Floor TELEPHONE: 212-798-8598 New York, NY 10281 ORGANIZATION (if any): * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 1. NAME OF DISTRICT South End Historic District 2. COUNTY Westchester TOWN/CITY VILLAGE Tarrytown 3. DESCRIPTION: See Continuation Sheet 4. SIGNIFICANCE: See Continuation Sheet 5. MAP See Continuation Sheet 6. SOURCES: See Continuation Sheet 7. THREATS TO AREA: BY ZONING BY ROADS BY DEVELOPERS BY DETERIORATION OTHER ADDITIONAL COMMENTS: 8. LOCAL ATTITUDES TOWARD THE AREA: 9. PHOTOS: See Continuation Sheet South End Historic District Physical Description The South End Historic District is located in the Village of Tarrytown, Town of Greenburgh, Westchester County, New York. The district is located on the west side of South Broadway (US Route 9). The district is situated within the area of potential effect (APE), and ranges from approximately 3,000 feet to 1½ miles south of the Tappan Zee Bridge and the New York State Thruway (Interstate [I]-87/287). It is also situated east of the Metro-North Railroad Hudson Line right-of-way (ROW) (see Location Map). The district was originally designated a local historic district by the Village of Tarrytown Historic Architectural Review Board (HARB) in 1980, and is characterized by multiple estates, including the National Historic Landmark (NHL)/National Register-listed Lyndhurst and Sunnyside, and two additional estates known as Belvedere and Shadowbrook. -

PDF Guidebook

Guidebook: Great Houses LOWER HUDSON Kykuit, The Rockefeller Estate http://www.hudsonvalley.org/kykuit/index.htm Pocantico Hills Tarrytown, NY 10591 Hours: House and Garden open from May through November (Closed Tuesdays) 10:00-3:00, weekends 10:00-4:00. Garden and Scuplture tours depart 11:15 AM Wed, Sat, & Sun. Notes: Groups tours available by reservation. Phone: (914) 631-9491 Historical Description: Completed in 1913 for John D. Rockefeller by architects William Adams Delano and Chester Holmes Aldrich, Kykuit has been home to four generations of Rockefeller family members. Visitors will see interiors designed by Ogden Codman, collections of Chinese and European ceramics, fine furnishings and galleries of twentieth-century art. Landscape architect William Welles Bosworth designed terraces and gardens with fountains, pavilions and classical sculpture; more than 70 works of modern sculpture were added during the 1960s and 70s. In the coach barn are horse drawn vehicles and classic automobiles. The Site: All tours of Kykuit begin at the Philipsburg Manor/Kykuit Visitor Center on Route 9 in Sleepy Hollow, New York. Tickets are sold on a first-come, first-served basis. While every effort is made to accommodate individuals in a timely manner, there may be waiting time for a tour. Please note that weekends are the busiest days, and tours may sell out by midday. The guided tour takes approximately 2 hours and is wheelchair accessible. Strollers and backpack carriers are not permitted. Parents are required to supply a car seat for the shuttle bus ride to Kykuit for children age 4 and under. You may also purchase gift certificates using a credit card by calling Historic Hudson Valley at (914) 631-9491. -

Village of Sleepy Hollow Section II

A. INTRODUCTION 1. Location The Village of Sleepy Hollow is located on the eastern shore of the Hudson River in Westchester County and has approximately 2.4 miles of waterfront on the Hudson River. Based on the 1990 U.S. Census, the Village of Sleepy Hollow has a population of 8,152. With this total, the population is broken down by race as follows: 6,634 white; 683 black; 41 Native American; 95 Asian or Pacific Islander; and 699 other race. The 1990 Census also reported 2,776 person ofHispanic origin (of any race) living in the Village. The Village is located approximately 15 miles north of New York City. While Sleepy Hollow certainly has its own local economy, the New York City metropolitan area is the major center of population, employment, and commercial activity in this region of the State. The regional setting ofthe Village is illustrated on the accompanying Map IB. The Village is within the Town ofMount Pleasant, and just north of the Village of Tarrytown and the eastern terminus of the Tappen Zee Bridge. Across the Hudson River are the Villages of South Nyack, Nyack, and North Nyack. Sleepy Hollow is situated very well with respect to major transportation routes and corridors. The New York State Thruway (Interstate 87 and 287) crosses the Hudson River just south ofthe Village of Sleepy Hollow at the Tappen Zee Bridge. The railroad is also a very prominent transportation feature of the Village I s western waterfront area. AMTRAK and Metro-North Commuter Railroad are the passenger railroad entities that provide transportation options for this region of the State. -

THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW a Journal of Regional Studies

SPRING 2018 THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. This issue of The Hudson River Valley Review has been generously underwritten by the following: Peter Bienstock THE POUGHKEEpsIE GRAND HOTEL SHAWANGUNK VALLEY AND CONFERENCE CENTER …centrally located in the Historic Hudson Valley CONSERVANCY midway between NYC and Albany… Conservation • Preservation • Education www.pokgrand.com From the Editors Welcome to our bigger, and more expansive, issue of The Hudson River Valley Review. As well as the enlarged format, we’ve widened the publication’s scope to accommodate more than 300 years of history. And while the topics covered in this issue might be broadly familiar, each essay offers details that reveal refreshing new insight. While the origins and evolution of Pinkster may be debatable, its celebration in seventeenth-century New Netherland offered an opportunity for residents—including enslaved African Americans—to relax, enjoy and express themselves. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, a French emigrant farmer drafted chapters of a book describing his new home in Orange County. These now-classic recollections would not be published until after he had been accused of disloyalty and chased out of the country. His eventual return—and the story of his trials and travels—is the stuff of cinema. In the early nineteenth century, another globetrotting writer, Washington Irving, helped to mold the young nation with his fiction and biographies. But the story of Irving’s own life is best conveyed at Sunnyside, his Westchester home, now preserved as a museum. -

The Hudson River Valley Review

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by The Hudson River Valley BG (Ret) Lance Betros, Provost, U.S. Army War Institute at Marist College. College Executive Director Kim Bridgford, Founder and Director, Poetry by James M. Johnson, the Sea Conference, West Chester University The Dr. Frank T. Bumpus Chair in Michael Groth, Professor of History, Frances Hudson River Valley History Tarlton Farenthold Presidential Professor, Research Assistant Wells College Erin Kane Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, Megan Kennedy State University of New York at New Paltz Emily Hope Lombardo Tom Lewis, Professor of English, Skidmore College Hudson River Valley Institute Advisory Board Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Alex Reese, Chair Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Barnabas McHenry, Vice Chair Roger Panetta, Visiting Professor of History, Peter Bienstock Fordham University Margaret R. Brinckerhoff H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English Emeritus, Dr. Frank T. Bumpus Vassar College Frank J. Doherty BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey Robyn L. Rosen, Professor of History, Shirley M. Handel Marist College Maureen Kangas David P. Schuyler, Arthur and Katherine Shadek Mary Etta Schneider Professor of Humanities and American Studies, Gayle Jane Tallardy Franklin & Marshall College Denise Doring VanBuren COL Ty Seidule, Professor and Head, Department Business Manager of History, U.S.