The Hudson River Valley Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 MISSION Boscobel House and Gardens preserves and shares the extraordinary beauty and historical significance of its Neoclassical mansion, renowned collection of early 19th-century decorative arts, and iconic Hudson River landscape. Boscobel embodies the Hudson Valley’s ongoing, dynamic exchange between design, history, and nature; and engages growing, diverse audiences in that conversation. VISION Boscobel inspires and informs visitors—from children and their families to subject specialists—through active and meaningful experiences of design, history, and nature. BOARD OF DIRECTORS, Summer 2018 STAFF, Summer 2018 Barnabas McHenry, President Jennifer Carlquist, Executive Director Elizabeth Gunther, Visitor Services / Alexander Reese, Vice President Design Shop Associate Linda Alfano, Events Assistant / Gardener Arnold Moss, Secretary and Treasurer Dana Hammond, Development Manager Deanna Argenio, Museum Guide Frances Hodes, Museum Guide William J. Burback JoAnn Bellia, Museum Guide Marie Horkan, Museum Guide Gilman S. Burke, Esq. Kendall Bland, Security Guard Stephen Hutcheson,Museum Guide Henry N. Christensen, Jr. Gunta Broderick, Bookkeeper Samuel Lawson, Jr., Museum Guide Susan Davidson Cliff Bowen, Maintenance Technician Emily Lombardo, Museum Guide Meg Downey Kathleen Burke, Museum Guide Jessica Lynn, Visitor Services / Robert G. Goelet Kasey Calnan, Collections Assistant / Design Shop Associate Col. James M. Johnson Design Shop Associate Harold MacAvery, Maintenance Technician Peter M. Kenny Elizabeth Chirico, Visitor -

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection Finding Aid Collection Overview Title: The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012 (bulk 1808-1896) Creator: Osterweis, Rollin G. (Rollin Gustav), 1907- Extent : 159 volumes; 1 linear foot of archival material Repository: Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives Abstract: This collection holds 159 volumes that make up the Rollin G. Osterweis Collection of Irving Editions and Irvingiana. It also contains one linear foot of archival materials related to the collection. Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Item title. (date) City: Publisher [if applicable]. The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012, (Date of Access). Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives. Historic Hudson Valley. Provenance: This collection was created by Rollin Gustav Osterweis and donated to Historic Hudson Valley by Ruth Osterweis Selig. 18 December 2012. Access: This collection is open for research with some restrictions based on the fragility of certain materials. Research restrictions for individual items are available on request. For more information contact the Historic Hudson Valley librarian, Catalina Hannan: [email protected]. Copyright: Copyright of materials belongs to Historic Hudson Valley. Permission to reprint materials must be obtained from Historic Hudson Valley. The collection contains some material copyrighted by other organizations and individuals. It is the responsibility of the researcher to obtain all permission(s) related to the reprinting or copying of materials. Processed by: Christina Neckles Kasman, February-August 2013 Osterweis Irving Collection - 1 Biographical Note Rollin Gustav Osterweis was a native of New Haven, Connecticut, where his grandfather had established a cigar factory in 1860. -

The Rockefellers an Enduring Legacy

The Rockefellers An Enduring Legacy 90 / OCTOBER 2012 / WWW.WESTCHESTERMAGAZINE.COM alfway through a three-hour tour The views from Kykuit were astound- of the Kykuit mansion, the for- ing—possibly the best in Westchester. The mer home to four generations Hudson sparkled like a thousand stars lit up of Rockefellers, it became appar- in the night sky. Surrounding towns, includ- ent that I was going to need to ing Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow, looked as Huse the bathroom—a large mug of iced coffee if civilization had yet to move in, the tree- purchased at a Tarrytown café was to blame. tops hiding any sign of human life. I felt like My guide, Corinne, a woman of perhaps 94, a time-traveler whisked back to a bygone era. Look around eagerly led me to a marble bathroom enclosed This must have been the view that had in- by velvet ropes, telling me this may have been spired John D. Rockefeller to purchase land you. How where John D. Rockefeller had spent a great in Westchester in 1893. New York City, where deal of his time. When, after several high- the majority of the Rockefeller family resided, much of decibel explanations, she gathered the nature was just 31 miles away and a horse-drawn car- of my request, I was ushered away from the riage could make the journey to the estate in the land, tour by two elderly women carrying walkie- less than two hours. It was the perfect family talkies, taken down a long flight of wooden retreat, a temporary escape from city life. -

6 Stops in Washington Irving's Sleepy Hollow

Built in 1913, Kykuit was the home of oil tycoon 6 STOPS IN WASHINGTON John D. Rockefeller. Depending on which Kykuit tour you choose, you’ll want to set aside 1.5 to 3 hours IRVING’S SLEEPY HOLLOW (includes a shuttle bus to the location). Book on the Historic Hudson Valley website. • Philipsburg Manor • Sculpture of the Headless Horseman Sculpture of the Headless Horseman • The Headless Horseman Bridge 362 Broadway, Sleepy Hollow, New York • The Old Dutch Church and Burying Ground After purchasing the guidebook Tales of The Old • Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Dutch Burying Ground from Philipsburg Manor, walk • Sunnyside towards the Old Dutch Burying Ground. There are _______________________ several photo opportunities along the way. Approximately 300 feet (100 metres) up the road Notes you’ll find the sculpture of the Headless Horseman. Double-check opening times before you travel to Sleepy Hollow. At the time of writing, locations like Sunnyside and This sculpture was created for those visiting Sleepy Philipsburg Manor are open Wednesday to Sunday, May to Hollow to help us explore and relive the town’s rich early November. heritage, keeping the legend alive. Looking for public restrooms along the way? Plan for stops at Philipsburg Manor,Tarrytown station and Sunnyside. The Headless Horseman Bridge _______________________ “Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road Take the CROTON-HARMON STATION bound Metro- that led to it, and the bridge itself, were thickly shaded by North Train from Grand Central Terminal and get off overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it, even in the daytime; but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. -

Promise of Pocantico

- Prepared by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation , Partnerships Greenrock Complex Orangerie and Greenhouses Conference Center and Coach Barn Kykuit and Stewardship The Playhouse Breuer House and Guest Houses The Parkland : Redevelopment and Reprogramming of Use Patterns The Greenrock Village: Office and Shop Buildings The Commons: Orangerie, Greenhouses, and Coach Barn The Extended Campus: The Playhouse, Breuer House, and Guest Houses Future Expansion Creating Connections Evolution of the Landscape Conceptual Plan Rockefeller Brothers Fund Philanthropy for an Interdependent World Lake Road Tarrytown, New York .. www.rbf.org Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC .. www.nthp.org © Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Inc. All rights reserved. Ben Asen Mary Louise Pierson RBF Staff : . The Pocantico Center represents another remarkable Rockefeller resource, one directed to ever- greater public benefit and managed through a thoughtful, principled process entirely consistent with family traditions and philanthropy. In the Pocantico Committee of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund was charged with developing a long-range plan for the Center that is economically feasible and responsive to the surrounding community, and provides an enriching experience for a range of visitors. This report presents the plan that was approved by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund board on June , as a guide for future activity together with its partner, the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Over the past two years, the Committee drew upon many experts and professionals in relevant areas, conducted assessments of outside operations, and held meetings full of concentrated debate, examination, and discovery. The final product is a comprehensive document aligning statements of Mission, Vision, and Principles with insightful program initiatives and responsible financial considerations, all based upon the significant history and assets of Pocantico. -

French Sculpture Census / Répertoire De Sculpture Française

FRENCH SCULPTURE CENSUS / RÉPERTOIRE DE SCULPTURE FRANÇAISE MAILLOL, Aristide Banyuls-sur-Mer, Pyrénées-Orientales 1861 - Banyuls-sur- Mer, Pyrénées-Orientales 1944 Baigneuse se coiffant Bather Putting Up her Hair 1898 bronze statue Acc. No.: Credit Line: Kykuit, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Nelson A. Rockefeller bequest Photo credit: ph. gardenia.net © Artist : Sleepy Hollow, New York, Kykuit, John D. Rockefeller Estate www.hudsonvalley.org/historic-sites/kykuit Comment International Sculpture Center website, Kykuit gardens, August 18, 2015: Kykuit, completed in 1913 for John D. Rockefeller and home to four generations of the Rockefeller family, sits high above the eastern banks of the Hudson River over looking the Palisades. Within the gardens of Kykuit are two distinct collections of sculpture. The fountains, wellheads and classical figures - from ancient and Renaissance models or by American sculptors of the early 20th century - were assembled between 1906 and 1913 by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and landscape architect William Welles Bosworth. The terraces descending to the west and the formal geometric spaces defined by stone walls and box hedges are punctuated by the pergolas and fountains integral to Italian garden design. In 1963, Governor Nelson Rockefeller elaborated upon this tradition and brought to Kykuit works by Lachaise, Arp, Lipchitz, Marini and Giacometti, beginning the collection of modern sculpture that graces the park today. He continued to add pieces during his 16-year residence at Kykuit, taking great care in the precise siting of each. International in scope, this collection numbers more than 70 sculptures, and reflects many of the major trends of modern sculpture during the first three- quarters of the 20th-Century, including works by Maillol, Calder, Moore, Picasso, Noguchi, Meadmore, and Nadleman, among others. -

WORFIELD in the SEVENTEENTH CENTURY (PART 2) This Article Is

WORFIELD IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY (PART 2) This article is not specifically linked to Worfield but since the events described were of such national importance, happened so locally and must have involved the parish, I hope you will forgive this diversion. There is another reason for telling this story – it is a fantastic tale and who better to tell it than a parishioner who is a descendant of one of the key families involved The first English Civil War ended in 1646. King Charles 1 surrendered to the Scots but unfortunately for Charles the Scots made a deal with Parliament and the King was handed over to Parliament. In 1648 there was a second Civil War organised by the King from his prison on the Isle of Wight. This was soon put down by Oliver Cromwell. King Charles 1 was beheaded on 30th January 1649 for treason. The treasonable offence was waging war on his own people. England became a republic and was ruled as a Commonwealth by Oliver Cromwell until his death in 1658. There was a third Civil War in 1651 when King Charles 11 attempted to regain the throne, with the help of the Scots. The war began and ended with Charles' defeat at the Battle of Worcester on 3rd September 1651 and that is where this story begins. Charles was a brave soldier and reluctant to admit defeat. He urged his followers to fight, even as they were throwing down their arms. He rode up and down among them, shouting, “I had rather you would shoot me, than keep me alive to see the sad consequences of this fateful day.” But it was a lost cause. -

Oakwood House, 16, Old Coach Road, Bishops Wood, Stafford, Staffordshire, ST19 9AD Asking Price £650,000

EPC E Oakwood House, 16, Old Coach Road, Bishops Wood, Stafford, Staffordshire, ST19 9AD Asking Price £650,000 **EXTENSIVE FAMILY HOME, ** VERSATILE FAMILY HOME, ** IN AND OUT DRIVEWAY, ** LARGE PLOT, ** VILLAGE LOCATION,*( Oakwood House is located in the popular village of Bishops Wood, It is home to the Royal Oak public house, the first to be named after the nearby oak tree at Boscobel House in which King Charles II hid after the Battle of Worcester. Comuter links include within easy reach of major roads such as A5, M6 & M6 Toll. On entering the village of Bishops Wood from the A5 Watling Street, take the first left hand turning signposted Brewood and the property is located on the right hand side. Do you need a home that will cater for your ever growing family from their first steps in life right through to when your brood fly the nest -Lots of space is on offer at Oakwood House therefore viewing is recommended early to appreciate what this home offers. The home offers spacious and versatile accommodation and comprises of Entrance Hall, Large Lounge, Dining Room, Further Reception Room/ Snug, Breakfast Kitchen, Utility Room, Downstairs WC, Six good size Bedrooms, En-suite to Master, Family Bathroom. Externally the property boasts in and out driveway leading to garage and a private enclosed garden. Glorious views overlooking fields makes waking up easier. Viewing is essential to appreciate. Viewing arrangement by appointment 01543 503678 [email protected] Bairstow Eves, 13 Wolverhampton Road, Cannock, WS11 1AP https://www.bairstoweves.co.uk Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. -

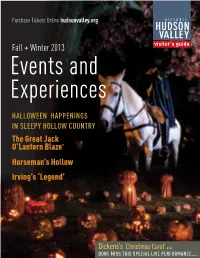

Fall + Winter 2013 Visitor's Guide Events and Experiences

Purchase Tickets Online hudsonvalley.org Fall + Winter 2013 visitor's guide Events and Experiences HALLOWEEN HAPPENINGS IN SLEEPY HOLLOW COUNTRY The Great Jack O’Lantern Blaze® Horseman’s Hollow Irving’s ‘Legend’ Dickens’s ‘Christmas Carol’ p.6A DONT MISS THIS SPECIAL LIVE PERFORMANCE.... 2A 3A SPECIAL EVENTS EVENTS SPECIAL SPOOKY AND SPECTACULAR FOR AGES 10+ Special Events FALL/WIN SEPTEMBER -DECEMBER 2013 ‘Best haunted house ever’ Historic Hudson Valley’s all-ages, TE family friendly special events ‘What an amazing experience… 2013 R draw tens of thousands of visitors so much fun and scare value’ each year. There is something ‘Makes me proud to live in Sleepy Hollow!’ here for everyone! October 5-6, 11-13, 18-20, 25-27 + November 1-2 —Facebook posts from Horseman’s Hollow visitors Irving's 'Legend' pg 2A Fridays: 6:15, 7:30, + 8:45pm Saturdays and Sundays: 5, 6:15, + 7:30pm The Legend Behind the 'Legend' pg 2A Irving’s ‘Legend’at Old Dutch Church Horseman's Hollow pg 3A SPELLBINDING foR AGES 10+ Accompanied by musician Jim Keyes, master storyteller Jonathan ® The Great Jack O’Lantern Blaze pg 4-5A Kruk — showcased on CBS Sunday Morning last year — offers a dramatic, spellbinding performance of Washington Irving’s classic tale, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Dickens's 'Christmas Carol' pg 6A ADVANCE TICKETS Adults, $16; Children under 18, $12 A Holiday Open House pg 6A ARE REQUIRED Members: $5 discount per ticket TICKets Oct 5-6, 11-13, 18-20, 25-27 + Nov 1-2 First admission at 7pm, last admission at 9:30pm (9pm Sundays) Many events SELL OUT and have limited capacity. -

An Evolved Understanding: an Examination of the National

AN EVOLVED UNDERSTANDING: AN EXAMINATION OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE’S APPROACH TO THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AT CHATHAM MANOR, FREDERICKSBURG AND SPOTSYLVANIA NATIONAL MILITARY PARK A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Olivia Holly Heckendorf August 2019 © 2019 Olivia Holly Heckendorf ii ABSTRACT Chatham Manor became part of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park in December 1975 after the death of its last private owner, John Lee Pratt. Constructed between 1768 and 1771, Chatham Manor has always been intertwined with the landscape and has gained significance throughout its 250-year lifespan. With each subsequent owner and period of time Chatham Manor has gained significance as a cultural landscape. Since its acquisition in 1975, the National Park Service has grappled with the significance and interpretation of Chatham Manor as a cultural landscape. This thesis provides an analysis of the National Park Service’s ideas of significance and interpretation of the cultural landscape at Chatham Manor. This is done through a discussion of several interpretive planning documents and correspondences from the staff of the National Park Service, including interpretive prospectuses, a general management plan, and long-range interpretive plan. In addition, the influence of both superintendents and staff is taken into consideration. Through the analysis of these documents, it was realized that the understanding of cultural landscapes is continuing to evolve within the National Park Service. In the 1960s and 1970s Chatham Manor was considered significant and interpreted almost solely for its association with the Civil War. -

Here We Are on the 200Th Anniversary of His Classic Story, Celebrating His Legacy of Artistic Inspiration and Achievement at the Nexus of the Tale Itself

WELCOME 1ST ANNUAL SLEEPY HOLLOW INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Could Washington Irving have predicted the enduring impact “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” would have on the world when it was published in 1819? Perhaps not. And yet here we are on the 200th anniversary of his classic story, celebrating his legacy of artistic inspiration and achievement at the nexus of the tale itself. The Sleepy Hollow International Film Festival is a celebration of cinematic and literary-themed wonders—a one-of-a-kind combination of film premieres, exclusive screenings, live events, scripts in competition as well as special guests, panels and much more, all taking place in the historic Hudson Valley during its magical, and wildly popular, Halloween season. All of us with SHIFF are thrilled to welcome you to be part of history with this first-ever large-scale genre film festival in Westchester County, NY, in one of the most famous locations in the entire world. We extend a special thanks to the fine folk, governments and associations of Sleepy Hollow and Tarrytown, the wondrous Tarrytown Music Hall and Warner Library, who proudly keep the spirit of Irving alive each and every day. So, for the next four days, revel in the inception of a new legend here in the Hollow. Enjoy, and let the bewitching begin! —The SHIFF Team Co-Founder/Director, Business Affairs DAVE NORRIS Advisory Board Lead Programmer DAN McKEON CHRIS POGGIALI FREDERICK K. KELLER TAYLOR WHITE Screenplay Board CHRIS TOWNSEND HARRY MANFREDINI Co-Founder/Director, DON LAMOREAUX Tech/Prints STEVE MITCHELL Programmer STEVE MITCHELL ZACH TOW CYRUS VORIS MATT VERBOYS CYRUS VORIS Official Photographer LARRY COHEN (In Memoriam. -

To Open the 2016 Report

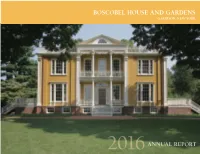

BOSCOBEL HOUSE AND GARDENS GARRISON, NEW YORK 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Boscobel Mission Statement Board of Directors, Spring 2017 Barnabas McHenry, President Meg Downey The Mission of Boscobel House Alexander Reese, Vice President Robert G. Goelet and Gardens is to enrich the lives Arnold Moss, Secretary Col. James M. Johnson Col. Williams L. Harrison Jr., Treasurer Peter Kenny of its visitors with memorable John S. Bliss Frederick H. Osborn, III experiences of the history, culture William J. Burback Susan Hand Patterson and environment of the Hudson Gilman S. Burke McKelden Smith Henry N. Christensen, Jr. Margaret Tobin River Valley. Susan Davidson Denise Doring VanBuren Boscobel Brand Idea Staff Steven Miller, Executive Director Joseph Gocha, Maintenance The past shapes who we are Linda Alfano, Maintenance Patrick Griffin,Docen t today – our culture, our style, JoAnn Bellia, Docent Edward Griffiths,Security Kendall Bland, Security Liz Gunther, Visitor Services our values and our traditions. Chloe Blaney, Gift Shop Frances Hodes, Docent The history of the Early Republic Donna Blaney, Marketing & Events Manager Marie Horkan, Docent Cliff Bowen, Maintenance Stephen Hutcheson, Docent is woven into the fabric of our Gunta Broderick, Bookkeeper Samuel Lawson, Docent society. It lives on through stories Kathy Burke, Docent Emily Lombardo, Docent Kasey Calnan, Gift Shop John Malone, Facilities Manager and experiences here. Boscobel’s Jennifer Carlquist, Curator Harold MacAvery, Maintenance extraordinary location in the Russel Cox, Maintenance Carolyn McShea, Development Assistant Hudson River Valley offers an Betty Chirico, Visitor Services Linda Moore, Visitor Services Lisa DiMarzo, Museum Educator Mary Nolan, Gift Shop immersive window into our past, Renee Edelman, Docent Dorothy Scheno, Docent bringing it to life to enrich and Colleen Fogarty, Property Rental Manager Charles Shay, Docent Maria Gaffney, Gift Shop Renate Smoller, Gift Shop Manager delight our visitors in a way that Edward Glisson, Visitor Services Manager Pat Turner, Housekeeping is relevant today.