Le Goff Among Mentalities, Memory, and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacques Le Goff's Round the World Tour 39

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert JACQUES LE GOFF’S ROUND THE WORLD TOUR DANIELA ROMAGNOLI UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PARMA ITALY Date of receipt: 2nd of June, 2014 Final date of acceptance: 10th of September, 2014 ABSTRACT This paper investigates the dissemination of the work of Jacques Le Goff in an international perspective, through the presence of his works in university and national libraries chosen as samples in all continents. In addition, and perhaps more than the original editions, translations into the languages of the various countries are interesting, as obviously reaching an audience both broader and less specifically trained than the “insiders”. Another impSortant point is the time of diffusion, not only of Le Goff’s work, but also of 20th century French historical thought —the so- called “Annales school”— and the overcoming of barriers between historiography and other human sciences, such as anthropology and ethnology; the differences between diverse cultures are evident and relevant. KEY WORDS Historiography, Middle Ages, Annales, Diffusion, Translation. CAPITALIA VERBA Historiographia, Medium Aevum, Annales, Diffusio, Traductio. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, VIII (2014) 37-60. ISSN 1888-3931 37 38 DANIELA ROMAGNOLI Jacques Le Goff celebrated his 90th birthday on the 1st of January 2014. This essay is certainly a tribute to this great medievalist but not in any celebratory sense. My intention is rather to supply a few more elements for understanding the meaning and popularity of the work of a historian who never shut himself up in a so-called ivory tower or closed himself off from the contemporary world around him. -

Marc Ferro E Os Cinejornais Em Histoire Parallèle Tempo, Vol

Tempo ISSN: 1413-7704 [email protected] Universidade Federal Fluminense Brasil Schvarzman, Sheila Construindo a história na televisão: Marc Ferro e os Cinejornais em Histoire Parallèle Tempo, vol. 20, 2014, pp. 1-22 Universidade Federal Fluminense Niterói, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=167031535025 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: 10.1590/TEM-1980-542X-2014203622 Revista Tempo | 2014 v20 | Article Constructing history on television: Marc Ferro and newsreels in Histoire Parallèle Sheila Schvarzman[1] Abstract In 1989, when Europe was being transformed after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the expansion of satellite communications, La Sept, a Franco-German TV channel, came into being. Histoire Paralèlle, a TV show hosted by Marc Ferro with newsreels shown in both countries, 50 years before, became the most watched program of the station, comparing the images the ways in which German and French started the war, as it should be seen and experienced by their fellow citizens. The program became a social- ized process of understanding and historical rewriting, besides standing before the conflict between memory and history, a ques- tion that guided the historiography of the 1990s. This article analyzes Histoire Paralèlle, examining the relationship that it estab- lished with the historiography and filmic production of the historian. Therefore, its theoretical assumptions are re-discussed and historicized in the context of Ferro’s works and through the analysis of three of his programs. -

La France Et L'europe Classique

La France et l'Europe classique Autor(en): Piuz, Anne-Marie Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte = Revue suisse d'histoire = Rivista storica svizzera Band (Jahr): 18 (1968) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 25.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-80606 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch «Irren wir nicht», so schließt Kaegi S. 104 einen Abschnitt, «so hängt die Breite des Einflusses von Jacob Burckhardts Wort und die Kraft seiner Wirkung auf die gebildete Basler Bevölkerung wesentlich von der Tatsache ab, daß er nicht nur im Hörsaal der philosophischen Fakultät eine kleine Auswahl von Studenten, sondern im Schulzimmer des Pädagogiums fast alle künftigen Gebildeten der Stadt in regelmäßigen zweijährigen Kursen von drei und vier Wochenstunden unterrichtet hat. -

History and Theory (His2c01)

HISTORY AND THEORY (HIS2C01) STUDY MATERIAL II SEMESTER CORE COURSE M.A. HISTORY (2019 Admission onwards) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION CALICUT UNIVERSITY P.O. MALAPPURAM - 673 635, KERALA 190505 School of Distance Education, University of Calicut 1 School of Distance Education, University of Calicut 2 HIS2C01 : HISTORY AND THEORY SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT STUDY MATERIAL SECOND SEMESTER M.A. HISTORY (2019 Admission onwards) CORE COURSE: HIS2C01 : HISTORY AND THEORY Prepared by: Dr. MYTHRI P U Assistant Professor (on contract) Department of History University of Calicut Scrutinized by: Sri. MUJEEB RAHIMAN K.G. Assistant Professor Department of History Govt. Arts & Science College Calicut School of Distance Education, University of Calicut 3 HIS2C01 : HISTORY AND THEORY School of Distance Education, University of Calicut 4 HIS2C01 : HISTORY AND THEORY CONTENTS Module I Enlightenment and the Perception of Historical Past 7 Module II History and Classical Social theory 35 Module III The Annales 63 Module IV Methodological Debates and Contemporary Trends 84 School of Distance Education, University of Calicut 5 HIS2C01 : HISTORY AND THEORY School of Distance Education, University of Calicut 6 HIS2C01 : HISTORY AND THEORY Module 1 Enlightenment and the Perception of Historical Past Vico Giovanni Battista Vico (1668–1744) spent most of his professional life as Professor of Rhetoric at the University of Naples. He was trained in jurisprudence, but read widely in Classics, philology, and philosophy, all of which informed his highly original views on history, historiography, and culture. His thought is most fully expressed in his mature work, the Scienza Nuova or The New Science. -

Exploring Historical Anthropology Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J

Exploring Historical Anthropology Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J. Gurevich Leonore Scholze-Irrlit z Scholze-Irrlitz, Leonore 1994 : Exploring Historical Anthropology. Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J. Gurevich . - Ethnologia Europaea 24: 119-132. The different styles of research of two historians - Jacques Le Goff and Aaron J . Gurevich - are analysed and compared. Both understand anthropology as th e basis of a new all-encompassing attempt at synthesising historical studies, and produce ind ependent results by taking into consideration lit erary-hermeneut ical, ethnological and structuralistic methods, thus forming two different co existing "styles of relationship" of medieval mentality. Le Goff and Gurevich contribute to historical anthropology and to a publicly effective renewal of the science of history through explanatory, deterministic and contemporary exam ination. An interview with A. J. Gurevich on the relationship between social history and the history of mentality is published as an append ix. Dr. phil. Leonore Scholze-Irrlitz, Eichbergstr. 23, D-12589 Berlin-Wilhelmsha gen. This paper deals with the styles of research and space (Le Goff 1970: 215 and 1977: 25, Le and the methods of Jacques Le Goff and Aaron Goff & Chartier 1990: 13). Significant for the J. Gurevich - two historians from very differ "Annales" school and also for Le Goff are fur ent scientific traditions. The contribution both ther the comparative methods of historical in of these medieval specialists have made to his terpretation and the concept of "histoire to torical anthropology reveals new dimensions tale" (Le Goff 1983 : XI, Honegger 1977: 13-14, in the science of history. Burke 1991: 29). The "Annales" went through three stages of development, the last of which is characterized by J. -

Resena.Pdf (85.46Kb)

Reseña. Cortés Riera. La escuela de los Anales 80 AÑOS DE LA ESCUELA DE LOS ANALES Luis Eduardo Cortés Riera. [email protected] El 15 de enero de 1929 nació la Revista de la que iba a ser la afamada Escuela de los Anales, un tercer hito historiográfico como el positivismo y el marxismo. Esta publicación fue dirigida por dos grandes historiadores franceses, Marc Bloch y Lucien Febvre, quienes eran ya unos reconocidos historiadores al haber publicado Los reyes taumaturgos, el primero y Martín Lutero. Un destino, el segundo. Esta Escuela se ha especializado en el estudio de las estructuras mentales y se le reconoce como el inicio de la llamada historia de las mentalidades colectivas. La ciudad Estrasburgo, en límites con Alemania, vio nacer la Escuela de los Anales, cuando el Estado francés creyó oportuno enviar allí lo mejor de su intelectualidad como contrapeso a la cultura germánica. En el primitivo directorio de la Revista de Anales figuran el sociólogo de la memoria Maurice Halbwachs, los historiadores Henry Hauser y el medievalista belga Henry Perenne, entre otros. Estos hombres se propusieron hacer una historia distinta a la de Leopold Von Ranke, es decir una historia no sólo política y afincada en los grandes hombres, batallas y tratados internacionales, sino una historia de todos los grupos humanos. En este sentido es una clara superación del historicismo alemán y del positivismo. Con Anales se produce una profunda imbricación de la historia con otras ciencias sociales: la geografía de Vidal de la Blanche, la sociología durkheniana, la antropología de Mauss y Levi Bruhl, la lingüística de Saussure, y eventualmente el psicoanálisis freudiano. -

Page 429 H-France Review Vol. 4 (December 2004), No. 123 Patrick

H-France Review Volume 4 (2004) Page 429 H-France Review Vol. 4 (December 2004), No. 123 Patrick H. Hutton, Philippe Ariès and the Politics of French Cultural History. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004. xxv + 244 pp. Notes, index, bibliography, and 20 illustrations. $80.00 US (cl). ISBN 1-55849-435-9; $24.95 US (pb). ISBN 1-55849-463-4. Review by Paul Mazgaj, University of North Carolina at Greensboro. It is only one of the many paradoxes surrounding the career of Philippe Ariès that he managed to find a niche in the French historical establishment only a few years before his death in 1984. Though a pioneer in the history of mentalités, for most of his life Ariès remained a self-styled "Sunday historian," continuing his day job for an institute involved in the trade of tropical fruit.[1] No less paradoxical is the fact that, while Ariès established a historical reputation as an innovator, he remained a life-long traditionalist, a disposition reflected in his personal life and habits, in his political choices, and, most profoundly, in his cultural preferences. Which leads to a last set of paradoxes. One might assume, given Ariès's traditionalism, that no cultural model could have been more distressing to him than America's, with its focus on the present rather than the past, its preference for the claims of the individual over those of the community, and its unabashed commercialism. Yet, Aris's first important professional recognition came not from France but from America, where Centuries of Childhood, the book that made his reputation, had its initial success.[2] And finally, in a related irony, twenty years after his death, it is an American historian, Patrick Hutton, who has produced the first major assessment of Ariès's life and work--an assessment, moreover, which convincingly argues for his importance not only as a historian but as a presence on the French intellectual scene in the closing decades of the twentieth century. -

Doctor Honoris Causa

- - UNIVERSITATEA DIN BUCUREŞTI ROGER CHARTIER Collège de France Doctor Honoris Causa - QBFFS Qvod Bene Felix Favstvmque Sit os illvstris Praeses senatvs et insignis Senatvs universitatis stvdiorvm bvcvrestiensis, praesentivm tenore maximo consensv, constitvimvs hodie svae celsitvdini Domino dignitatemoger hartier RDoctoris Honoris Cavsa Universitatis stvdiorvm bvcvrestiensisC conferri. PRO EIVS REI MEMORIA HOC DIPLOMA REDIGENDVM ET MANDANDVM IVSSIMVS. UNIVERSITATEA DIN BUCUREŞTI praeses senatvs, Rector, ROGER CHARTIER Marian Preda Mircea Dvmitrv Collège de France Professor Ordinarius Professor Ordinarius - Doctor Honoris Causa Datum Bucurestiis, Pridie Idus Novembres, bis millesimo undevicesimo anno post Christum natum La reconnaissance de mon travail par l’Université de Bucarest a pour moi une signification toute particulière. Nous savons tous les liens anciens, solides et affectueux établis depuis longtemps entre la Roumanie et la France. Ils ont eu pour moi plusieurs visages. Tout d’abord, celui d’un historien qui a construit, malgré les vicissitudes de temps souvent douloureux, une œuvre majeure : Alexandru Duţu. J’aurais aimé qu’il puisse partager avec moi et avec vous ce moment. Il fut un pionnier dans le dialogue noué entre la tradition historiographique qui est la mienne, celle des Annales, et l’histoire intellectuelle et culturelle pratiquée dans le Sud-Est européen. J’ai croisé plusieurs fois (à Paris, à Wolfenbüttel, à Bucarest) les chemins suivis par ce magnifique historien des idées, des littératures et des cultures, qui -

O CINEMA COMO FONTE HISTÓRICA NA OBRA DE MARC FERRO Cinema As a Historial Source in the Works Marc Ferro

MORETTIN , E. V. O cinema como fonte histórica na obra... 11 O CINEMA COMO FONTE HISTÓRICA NA OBRA DE MARC FERRO Cinema as a historial source in the Works Marc Ferro Eduardo Victorio Morettin* RESUMO Este artigo analisa o lugar que o cinema ocupa como fonte histórica na obra de Marc Ferro. Além de examinar a relação entre história e o cinema em seus textos, ele também sistematiza as noções que comandam a reflexão de ferro sobre o tema. Por último, ressalta a maneira pela qual se efetiva esta relação por meio do estudo de alguns casos concretos, como os filmes feitos durante o período da República de Weimar. Palavras-chave: cinema, história, Marc Ferro. ABSTRACT This article analyzes the insertion of the cinema as a historical source in Marc Ferro’s work. Besides examining the relationship between history and cinema in his texts, it also presents some key elements that drive his reflection about the theme. Finally, this article highlights the way this relationship is put into practice, using concrete examples such as some of the films produced during Weimar’s Republic period. Key-words: film, history, Marc Ferro. Vários foram os pesquisadores que se preocuparam com a relação entre cinema e história. Não temos a intenção de apresentar a maneira pela qual esta questão foi pensada ao longo do tempo. Podemos, no entanto, afirmar que ela é tão antiga como o próprio cinema, como vemos em um documento de 1898, publicado na revista Cultures.1 No caso brasileiro, * Professor da Escola de Comunicação Artes - ECA da USP 1 LE CINÉMA et l’histoire: un document de 1898. -

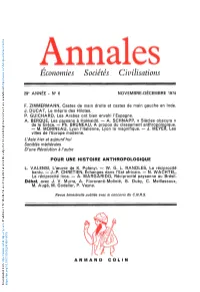

Economies Sociétés Civilisations

Annales Economies Sociétés Civilisations https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms 29e ANNÉE - N" 6 NOVEMBRE-DÉCEMBRE 1974 F. ZIMMERMANN, Castes de main droite et castes de main gauche en Inde. J. DUCAT, Le mépris des Hilotes. P. GUICHARD, Les Arabes ont bien envahi l'Espagne. A. BERQUE, Les paysans à Hokkaidô. — A. SCHNAPP, « Siècles obscurs » de la Grèce. — Ph. BRUNEAU, A propos du classement anthropologique. — M. MORINEAU, Lyon l'italienne, Lyon la magnifique. — J. MEYER, Les villes de l'Europe moderne. L'Asie hier et aujourd'hui Sociétés médiévales D'une Révolution à l'autre , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at POUR UNE HISTOIRE ANTHROPOLOGIQUE L VALENSI, L'œuvre de K. Polanyi. — W. G. L RANDLES, La réciprocité bantu. — J.-P. CHRÉTIEN, Échanges dans l'Est africain. - N. WACHTEL, La réciprocité inca. — A. MARGARIDO, Réciprocité paysanne au Brésil. 29 Sep 2021 at 22:22:06 Débat, avec J. V. Murra, A. Fioravanti-Molinié, G. Duby, C. Meillassoux, M. Auge, M. Godelier, P. Veyne. , on Revue bimestrielle publiée avec le concours du C.N.R.S. 170.106.202.58 . IP address: https://www.cambridge.org/core ARMAND COLIN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0395264900149078 Downloaded from . Annales Économies Sociétés Civilisations 29- ANNÉE - H' 6 NOVEMBRE-DÉCEMBRE 1974 SOMMAIRE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms POUR UNE HISTOIRE ANTHROPOLOGIQUE: LA NOTION DE RÉCIPROCITÉ Introduction 1309 Lucette VALENSI, Anthropologie économique et Histoire 1311 W. G. L. RANDLES, La réciprocité en Afrique bantu 1320 Jean-Pierre CHRÉTIEN, Échanges et hiérarchies dans les royaumes des Grands Lacs de l'Est africain 1327 Alfredo MARGARIDO, La réciprocité dans un mouvement paysan du Sud du Brésil 1338 Nathan WACHTEL, La réciprocité et l'État inca : de Karl Polanyi à John V. -

China and the Writing of World History in the West

China and the Writing of World History in the West Paper prepared for the XIXth International Congress of Historical Sciences (Oslo, 6-13 August 2000) Gregory Blue Department of History University of Victoria Victoria, B.C., Canada <[email protected]> 1 China and the Writing of World History in the West1 Paper prepared for the XIXth International Congress of Historical Sciences (Oslo, 6-13 August 2000) Gregory Blue University of Victoria Recent controversies over multicultural education in the West, particularly some of the heated exchanges about the possibility of introducing more globally oriented alternatives to the standard 'western civilisation' course, at times obscure the fact that world history is a long established genre that has occupied scholars for centuries and has had an enduring appeal for diverse types of readers for just as long. Whatever the current pedagogical concerns regarding it, the scholarly pedigree of world history is difficult to deny. Traditionalists within the historical profession who associate it solely with the grand schemes of Spengler and Toynbee, or who voice dismay because they identify with certain schools of social scientific thought, can be reminded that no less a figure than Leopold von Ranke crowned his career by devoting his last years to the writing of his own seven-volume Weltgeschichte (1881-1888). Leaving aside the faults of that work – and its convinced Eurocentrism may now be counted among the gravest – the significance Ranke attached to it and the fact that in undertaking it he put his own legitimising stamp on a genre conventionally recognised as having a lineage extending back in the West to Herodotus and the Bible suggests that world history cannot easily be dismissed as merely a trendy form of inquiry cultivated only on the margins of the discipline.2 A general theoretical justification for a global approach to history was already clearly formulated for mainstream historians at the beginning of the twentieth century, for example, by Henry Smith Williams in his monumental Historians' History of the World. -

El Estudio De La Cultura Material, Interés De Las Ciencias Históricas Y Antropológicas

EL ESTUDIO DE LA CULTURA MATERIAL, INTERÉS DE LAS CIENCIAS HISTÓRICAS Y ANTROPOLÓGICAS ISMAEL SARMIENTO RAMÍREZ HISTORIADOR CUBANO RESUMEN: EL ESTUDIO AGRUPA LOS PRINCIPALES APORTES QUE HAN FAVORECIDO A LA INTEGRACIÓN HISTORIA- ANTROPOLOGÍA E INSISTE EN AQUELLOS QUE INCIDEN EN LA ARTICULACIÓN DE AMBAS CIENCIAS CON LA HISTORIA DE LA CULTURA MATERIAL. PRIMERO SE REFLEXIONA EN TORNO A LA INTERDISCIPLINARIEDAD DE LAS CIENCIAS HISTÓRI- CAS Y ANTROPOLÓGICAS; Y LUEGO EN LOS NUEVOS CAMINOS DE LA HISTORIA QUE SIN DUDAS FAVORECEN EL ESTUDIO DE LA CULTURA MATERIAL. PALABRAS CLAVE: Historia, antropología, cul- material culture. The text reflects, first, around the tura material, interdisciplinaridad, teoría. link between history and anthropology, and, secondly, on the new paths open to history, which ABSTRACT: This study deals with the main stu- indeed favour the study of material culture. dies that have helped the blend of history and anthropology and strengthens those which focus in KEY WORDS: History; Anthropology; Material the connections of both sciences with the history of Culture, Link, Theory. ANALES DEL MUSEO DE AMÉRICA 13 (2005). PÁGS. 317-338 [ 317 ] ISMAEL SARMIENTO RAMÍREZ I INTRODUCCIÓN Con este esbozo no pretendo presentar un estudio profundo del quehacer inter- disciplinario de las ciencias históricas y antropológicas; y menos aún hacer un análisis exhaustivo de todas las corrientes historiográficas contemporáneas: ambas labores en la actualidad son en extremo complejas y sus debates abundan en la historiografía. Aquí, tan solo parto de los principales aportes que han favorecido a la interacción historia- antropología para insistir en aquellos que inciden en la articulación de ambas ciencias con la historia de la cultura material; resultados que, de una u otra forma, han influido en el diseño, el desarrollo y la consecución final de otras de mis investigaciones, princi- palmente, en: Cuba entre la opulencia y la pobreza.