Visual Spoofing of SSL Protected Web Sites and Effective Countermeasures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of Anti-Phishing Mechanisms: Email Phishing

Volume 8, No. 3, March – April 2017 ISSN No. 0976-5697 International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science REVIEW ARTICLE Available Online at www.ijarcs.info A Comparative Analysis of Anti-Phishing Mechanisms: Email Phishing ShwetaSankhwar and Dhirendra Pandey BabasahebBhimraoAmbedkar University Lucknow, U. P., India Abstract: Phishing has created a serious threat towards internet security. Phish e-mails are used chiefly to deceive confidential information of individual and organizations. Phishing e-mails entice naïve users and organizations to reveal confidential information such as, personal details, passwords, account numbers, credit card pins, etc. Phisher spread spoofed e-mails as coming from legitimate sources, phishers gain access to such sensitive information that eventually results in identity and financial losses.In this research paper,aexhaustive study is done on anti-phishing mechanism from year 2002 to 2014. A comparative analysis report of anti-phishing detection, prevention and protection mechanisms from last decade is listed. This comparativeanalysis reports the anti-phishing mechanism run on server side or client side and which vulnerable area is coverd by it. The vulnerable area is divided into three categories on the basis of email structure. The number of vulnerabilties covered by existing anti-phishing mechanisms are listed to identify the focus or unfocused vulnerability. This research paper could be said as tutorial of a existing anti-phishing research work from decade. The current work examines the effectiveness of the tools and techniques against email phishing. It aims to determine pitfalls and vulnerability of anti-phishing tools and techniques against email phishing. This work could improve the understanding of the security loopholes, the current solution space, and increase the accuracy or performance to counterfeit the phishing attack. -

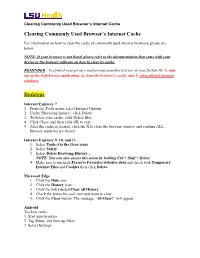

Clearing Commonly Used Browser's Internet Cache Desktops

Clearing Commonly Used Browser’s Internet Cache Clearing Commonly Used Browser’s Internet Cache For information on how to clear the cache of commonly used internet browsers, please see below. NOTE: If your browser is not listed, please refer to the documentation that came with your device or the browser software on how to clear its cache. REMINDER: To protect your privacy and prevent unauthorized use of your System ID, 1) sign out of the Self-Service application, 2) clear the browser’s cache, and 3) close all web browser windows. Desktops Internet Explorer 7 1. From the Tools menu, select Internet Options. 2. Under "Browsing history", click Delete. 3. To delete your cache, click Delete files. 4. Click Close, and then click OK to exit. 5. After the cache is cleared, click the X to close the browser window and confirm ALL browser windows are closed. Internet Explorer 9, 10, and 11 1. Select Tools (via the Gear icon) 2. Select Safety 3. Select Delete Browsing History… NOTE: You can also access this menu by holding Ctrl + Shift + Delete 4. Make sure to uncheck Preserve Favorites websites data and check both Temporary Internet Files and Cookies then click Delete. Microsoft Edge 1. Click the Hub icon. 2. Click the History icon. 3. Click the link labeled Clear all History. 4. Check the boxes for each item you want to clear. 5. Click the Clear button. The message “All Clear!” will appear. Android To clear cache: 1. Start your browser. 2. Tap Menu, and then tap More. 3. Select Settings. -

Taskstream Technical & System Faqs

Taskstream Technical & System FAQs 71 WEST 23RD STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10010 · T 1.800.311.5656 · e [email protected] Taskstream FAQs Taskstream FAQs Click the links in each question or description to navigate to the answer: System Requirements FAQs . What Internet browsers can I use to access Taskstream? . Can I use Taskstream on a Mac or a PC? on a desktop or laptop computer? . Does Taskstream work on iPad, iPhone or Android-based devices? . Do I need additional plugins or add-ons to use Taskstream? . Can I access Taskstream offline? . Does Taskstream require JavaScript to be enabled? . Does Taskstream require cookies to be enabled? . Does Taskstream use pop-ups? . How can I import and export data within Taskstream? Technical FAQs . Can I have Taskstream open in more than one window at a time? . Is Taskstream's site accessible to users with disabilities? . What is a Comma Separated Value (CSV) file? . How do I print my work? . How do I format my text? . How do I add special characters, such as math symbols or special punctuation, to my text? . What is WebMarker File Markup? . What is Turnitin® Originality Reporting? . Can I change the size of the Taskstream text/fonts? Troubleshooting . When I click on a button nothing occurs. Some of the features within the Taskstream site are missing. When I try to download/view a file attachment, nothing happens. I am not receiving emails from Taskstream. I uploaded a file on my Mac, but the attached file does not open. My file is too large to upload. Taskstream is reporting that I have entered unsafe text. -

How to Layer and Sell Security Solutions to Protect Your Clients’ Remote Workers, Data, and Devices

How to Layer and Sell Security Solutions to Protect Your Clients’ Remote Workers, Data, and Devices PAX8 | PAX8.COM ©2021 Pax8 Inc. All rights reserved. Last updated April 2021. About This Guide This guide offers recommendations to build a layered remote security stack and position it to your clients to keep them productive and secure while working remotely. Introduction Shifting the Security Focus: From the Perimeter to Endpoints 2 Building the Foundation for Remote Security 1. Put Endpoint Security in Place 3 2. Layer on Additional Email Security 4 3. Begin Ongoing End User Security Training 5 Standardizing Your Remote Security Stack: Trending Solutions 6 Fortifying Remote Defenses Other Tools to Secure Remote Work Environments 7 Advancing the Conversation Remote Security Checklist 8 Email Template for Layered Security 9 Education, Enablement & Professional Services Your Expert for Secure Remote Work 10 [email protected] | +1 (855) 884-7298 | pax8.com INTRODUCTION A Shift in Security Focus: While the global spike in remote work in 2020 helped many companies stay productive, it also increased security challenges as employees remotely accessed company networks, of remote workers say files, and data. With more employees working outside their biggest challenge of the safety of perimeter security related to the is collaboration and corporate network and firewalls, IT security focus communication1 shifted to endpoints, email, and end users as the first line of defense. A Wave of COVID-19 Related Cyber Risks: The surge in remote work due to COVID-19 (and the resulting security vulnerabilities) fueled an alarming rise in cybercrime – the FBI reported in August 2020 that cyberattack complaints were up by 400%!2 Microsoft reported that pandemic-themed phishing and social engineering attacks jumped by 10,000 a day, while cybersecurity experts reported that ransomware attacks were up by 800%. -

Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0091418 A1 Gonzalez (43) Pub

US 2013 009 1418A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0091418 A1 Gonzalez (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 11, 2013 (54) CROSS-BROWSER TOOLBAR AND METHOD Publication Classification THEREOF (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: Visicom Media Inc., Brossard (CA) G06F 7/2 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventor: Miguel Enrique Cepero Gonzalez, CPC .................................... G06F 17/218 (2013.01) Brossard (CA) USPC .......................................................... 71.5/234 (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: VISICOMMEDIA INC., Brossard A tool configured to build a cross-browser toolbar is pro (CA) vided. The tool comprises a processor; and a memory coupled to the processor and configured to store at least instructions for execution of a wizard program by the processor, wherein (21) Appl. No.: 13/690,236 the wizard program causes to: receive an input identifying at least user interface elements and event handlers respective of the user interface elements, wherein the input further identi (22) Filed: Nov.30, 2012 fies at least two different types of a web browser on which the toolbar can be executed; generate respective of the received O O input a toolbar render object, a script file, and at least one Related U.S. Application Data toolbar library for each type of web browser; and compile the (63) Continuation of application No. 12/270,421, filed on toolbar render object, the script file, and the least one toolbar Nov. 13, 2008, now Pat. No. 8,341,608. library into an installer file. 120-1 Installer Web File BrOWSer TOOlbar Builder installer File TOOlbar BrOWSer Libraries Patent Application Publication Apr. -

CHUENCHUJIT-THESIS-2016.Pdf

c 2016 Thasphon Chuenchujit A TAXONOMY OF PHISHING RESEARCH BY THASPHON CHUENCHUJIT THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Associate Professor Michael Bailey ABSTRACT Phishing is a widespread threat that has attracted a lot of attention from the security community. A significant amount of research has focused on designing automated mitigation techniques. However, these techniques have largely only proven successful at catching previously witnessed phishing cam- paigns. Characteristics of phishing emails and web pages were thoroughly analyzed, but not enough emphasis was put on exploring alternate attack vectors. Novel education approaches were shown to be effective at teach- ing users to recognize phishing attacks and are adaptable to other kinds of threats. In this thesis, we explore a large amount of existing literature on phishing and present a comprehensive taxonomy of the current state of phish- ing research. With our extensive literature review, we will illuminate both areas of phishing research we believe will prove fruitful and areas that seem to be oversaturated. ii In memory of Nunta Hotrakitya. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitute to Professor Michael Bailey for guiding this work from start to finish. I also greatly appreciate the essential assistance given by Joshua Mason and Zane Ma. Finally, I wish to thank my parents for their love and support throughout my life. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 2 RELATED WORK . 3 CHAPTER 3 ATTACK CHARACTERISTICS . -

Utilising the Concept of Human-As-A-Security-Sensor for Detecting Semantic Social Engineering Attacks

Utilising the concept of Human-as-a-Security-Sensor for detecting semantic social engineering attacks Ryan John Heartfield A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 2017 Declaration \I certify that the work contained in this thesis, or any part of it, has not been accepted in substance for any previous degree awarded to me, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise identified by references and that the contents are not the outcome of any form of research misconduct." SUPERVISOR: ................................................ ............................... RYAN HEARTFIELD SUPERVISOR: ................................................ ............................... DR. GEORGE LOUKAS SUPERVISOR: ................................................ ............................... DR. DIANE GAN i Abstract Social engineering is used as an umbrella term for a broad spectrum of computer exploitations that employ a variety of attack vectors and strate- gies to psychologically manipulate a user. Semantic attacks are the spe- cific type of social engineering attacks that bypass technical defences by actively manipulating object characteristics, such as platform or system applications, to deceive rather than directly attack the user. Semantic social engineering -

Manage Pop-Up Blockers

Manage Pop-Up Blockers As pop-up blockers may interfere with the installation of plug-ins and players used in your course including opening and viewing activities, depending on your preference, you can either allow pop-ups from specific sites or disable browser pop-up blockers for all web sites. Disable Pop-up Blockers for All Sites Browser Instructions Internet From the browser Tools menu, select Pop-up Blocker, then Turn off Explorer Pop-up Blocker. From the Safari menu, clear the checkmark for Block pop-up Safari windows. Firefox From the Tools menu, select Options Chrome 1. Click the Chrome menu on the browser toolbar. 2. Select Settings. 3. Click Show advanced settings. 4. in the "Privacy" section, click the Content settings button. 5. In the "Pop-ups" section, select "Allow all sites to show pop-ups." Allow Pop-ups from Specific Sites (Exceptions) Browser Instructions When you see the yellow “Information Bar” at the top of the web page Internet about a pop-up being blocked, click the bar and select Always allow Explorer pop-ups from this site, and click Yes to confirm. –or– 1. From the browser Tools menu, select Pop-up Blocker, then Pop-up Blocker Settings. 2. Add the following as allowed sites: • *.pearsoned.com, • *.pearsoncmg.com • *.mylanguagelabs.com , • *mylabs.px.pearsoned.com, • *pearsonvt.wimba.com 3. Click Close. Safari In Safari you can either enable or disable the pop-up blocker. There is no per-site control. See next section for details on how to disable pop-up blocker. Firefox 1.From the Tools menu, select Options 2. -

How to Disable Your Browser's Popup Blockers How to Disable

Why I cannot open E-document? If nothing pops out after clicking “view”: Please disable your browser's Pop-up Blocker in order to open E-Documents. Use a different browser, such as Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari or Google Chrome. If a blank screen pops out after clicking “view”: Please update Java or Adobe reader. BOTH must be activated and updated to view E- documents. How to disable your browser's popup blockers The following includes steps for disabling pop-up window blockers. Internet Explorer 7, 8 9 or 10 (Windows PC) Internet Explorer 6 (Windows PC) Firefox (Windows PC) Firefox (Mac OSX) Safari (Mac OSX) Chrome (Windows PC) Chrome (Mac OSX) The following includes steps for disabling browser toolbars. Yahoo toolbar popup blocker Google toolbar popup blocker AOL toolbar popup blocker MSN toolbar popup blocker Norton Internet Security/Personal Firewall popup blocker How to disable Internet Explorer 7, 8, 9 or 10 popup blocker 1. From the Tools menu, select Internet Options. 2. From the Privacy tab, uncheck Turn on Pop-up Blocker and click "OK". For more information on Internet Explorer popup blocker please go to http://windows.microsoft.com/is-IS/windows7/Internet-Explorer-Pop-up-Blocker- frequently-asked-questions Back to top How to disable Internet Explorer 6 popup blocker (Windows PC) 1. From the Tools menu, select Internet Options. 2. From the Privacy tab, uncheck Block pop-ups. Back to top How to disable the Firefox popup blocker (Windows PC) 1. From the Tools menu, select Options. 2. From the Content tab, uncheck Block Popup Windows and click "OK". -

Mobile Malware Attacks and Defense Copyright © 2009 by Elsevier, Inc

Elsevier, Inc., the author(s), and any person or firm involved in the writing, editing, or production (collectively “Makers”) of this book (“the Work”) do not guarantee or warrant the results to be obtained from the Work. There is no guarantee of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the Work or its contents. The Work is sold AS IS and WITHOUT WARRANTY. You may have other legal rights, which vary from state to state. In no event will Makers be liable to you for damages, including any loss of profits, lost savings, or other incidental or consequential damages arising out from the Work or its contents. Because some states do not allow the exclusion or limitation of liability for consequential or incidental damages, the above limitation may not apply to you. You should always use reasonable care, including backup and other appropriate precautions, when working with computers, networks, data, and files. Syngress Media®, Syngress®, “Career Advancement Through Skill Enhancement®,” “Ask the Author UPDATE®,” and “Hack Proofing®,” are registered trademarks of Elsevier, Inc. “ Syngress: The Definition of a Serious Security Library”™, “Mission Critical™,” and “The Only Way to Stop a Hacker is to Think Like One™” are trademarks of Elsevier, Inc. Brands and product names mentioned in this book are trademarks or service marks of their respective companies. Unique Passcode 28475016 PUBLISHED BY Syngress Publishing, Inc. Elsevier, Inc. 30 Corporate Drive Burlington, MA 01803 Mobile Malware Attacks and Defense Copyright © 2009 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher, with the exception that the program listings may be entered, stored, and executed in a computer system, but they may not be reproduced for publication. -

Behavior-Based Spyware Detection

Behavior-based Spyware Detection Engin Kirda and Christopher Kruegel Secure Systems Lab Technical University Vienna {ek,chris}@seclab.tuwien.ac.at Greg Banks, Giovanni Vigna, and Richard A. Kemmerer Department of Computer Science University of California, Santa Barbara {nomed,vigna,kemm}@cs.ucsb.edu TECHNICAL REPORT Abstract Spyware is rapidly becoming a major security issue. Spyware programs are surreptitiously installed on a user’s workstation to monitor his/her actions and gather private information about a user’s behavior. Current anti-spyware tools operate in a way similar to traditional anti-virus tools, where signatures associated with known spyware programs are checked against newly-installed applications. Unfortunately, these techniques are very easy to evade by using simple obfuscation transformations. This paper presents a novel technique for spyware detection that is based on the characterization of spyware-like behavior. The technique is tailored to a popular class of spyware applications that use Internet Ex- plorer’s Browser Helper Object (BHO) and toolbar interfaces to monitor a user’s browsing behavior. Our technique uses a composition of static and dynamic analysis to determine whether the behavior of BHOs and toolbars in response to simulated browser events is to be considered mali- cious. The evaluation of our technique on a representative set of spyware samples shows that it is possible to reliably identify malicious components using an abstract behavioral characterization. Keywords: spyware, malware detection, static analysis, dynamic analy- sis. 1 Introduction Spyware is rapidly becoming one of the major threats to the security of Inter- net users [16, 19]. A comprehensive analysis performed by Webroot (an anti- spyware software producer) and Earthlink (a major Internet Service Provider) 1 showed that a large portion of Internet-connected computers are infected with spyware [1], and that, on average, each scanned host has 25 different spyware programs installed [6]. -

Emerging Technologies: New Developments in Web Browsing and Authoring

Language Learning & Technology February 2010, Volume 14, Number 1 http://llt.msu.edu/vol14num1/emerging.pdf pp. 9–15 EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES: NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN WEB BROWSING AND AUTHORING Robert Godwin-Jones Virginia Commonwealth University In this new decade of the 21st century, the Web is undergoing a significant transformation. Supplementing its traditional role of retrieving and displaying data, it is now becoming a vehicle for delivering Web-based applications, server-stored programs that feature sophisticated user interfaces and a full range of interactivity. Of course, it has long been possible to create interactive Web pages, but the interactivity has been more limited in scope and slower in execution than what is possible with locally- installed programs. The limitations in terms of page layout, interactive capabilities (like drag and drop), animations, media integration, and local data storage, may have had developers of Web-based language learning courseware yearning for the days of HyperCard and Toolbook. But now, with major new functionality being added to Web browsers, these limitations are, one by one, going away. Desktop applications are increasingly being made available in Web versions, even such substantial programs as Adobe PhotoShop and Microsoft Office. Included in this development are also commercial language learning applications, like Tell me More and Rosetta Stone. This movement has been accelerated by the growing popularity of smart phones, which feature full functionality Web browsers, able in many cases to run the same rich internet applications (RIA) as desktop Web browsers. A new Web-based operating system (OS) is even emerging, created by Google specifically to run Web applications.