PDF (Volume 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doxford International

Go North East Doxford International - Pennywell 39 via Moorside, Doxford Park, Ryhope, Grangetown, Sunderland, Royal Hospital, Chester Road Doxford International - Pennywell 39A via Moorside, Doxford Park, Esdale Estate, Ryhope, Grangetown, Sunderland, Royal Hospital, Chester Road Monday to Friday Ref.No.: 010 Commencing Date: 01/06/2020 Service No 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39A 39 39 39A 39 Doxford International Admiral Way . 0654 0704 0720 0732 0749 0806 0823 0838 0858 0912 0931 0947 1004 1017 1034 47 04 17 34 1404 1417 1434 Moorside Midgley Drive . 0657 0707 0723 0735 0752 0809 0826 0841 0901 0915 0934 0950 1007 1020 1037 50 07 20 37 1407 1420 1437 Doxford Park Shops . 0659 0709 0725 0737 0754 0811 0828 0843 0903 0917 0936 0952 1009 1022 1039 52 09 22 39 1409 1422 1439 Tunstall Village Green . 0704 0713 0729 0742 0759 0816 0832 0847 0907 0921 0940 0956 1013 1026 1043 56 13 26 43 1413 1426 1443 Esdale Estate Bevan Avenue Top . ---- 0717 ---- 0746 ---- 0820 ---- 0851 ---- 0925 ---- 1000 ---- 1030 ---- 00 ---- 30 ---- ---- 1430 ---- Ryhope Green . 0708 0720 0734 0749 0804 0823 0838 0854 0912 0928 0945 1003 1018 1033 1048 03 18 33 48 mins. 1418 1433 1448 Grangetown Stockton Terrace . 0712 0724 0738 0754 0809 0828 0843 0859 0917 0933 0950 1008 1023 1038 1053 08 23 38 53 past 1423 1438 1453 Sunderland Winter Gardens . Arr 0719 0731 0745 0801 0816 0835 0850 0906 0924 0940 0957 1015 1030 1045 1100 then 15 30 45 00 each 1430 1445 1500 Sunderland Winter Gardens . -

Doxford International - Sunderland - Pennywell Go North East 39 Effective From: 05/09/2021

Doxford International - Sunderland - Pennywell Go North East 39 Effective from: 05/09/2021 Doxford InternationalDoxford AdmiralPk Shops,Tunstall Way Doxford Village Pk Way GreenRyhope Village Grangetown Sunderland WinterSunderland, Gdns, Borough HolmesideUniversity, Road ChesterSunderland Road Campus RoyalSunderland Hospital CrematoriumPennywell, Shopping Centre Approx. 2 11 13 22 26 29 31 34 38 41 journey times Monday to Friday Doxford International Admiral Way 0654 0720 0749 0823 0858 0931 1004 1034 1104 1134 1204 1234 1304 1334 1404 Doxford Pk Shops, Doxford Pk Way 0656 0722 0751 0825 0900 0933 1006 1036 1106 1136 1206 1236 1306 1336 1406 Tunstall Village Green 0705 0731 0801 0835 0909 0942 1015 1045 1115 1145 1215 1245 1315 1345 1415 Ryhope Village 0708 0734 0804 0838 0912 0945 1018 1048 1118 1148 1218 1248 1318 1348 1418 Grangetown 0715 0741 0812 0846 0920 0953 1026 1056 1126 1156 1226 1256 1326 1356 1426 Sunderland Winter Gdns, Borough Road arr 0719 0745 0816 0850 0924 0957 1030 1100 1130 1200 1230 1300 1330 1400 1430 Sunderland Winter Gdns, Borough Road dep 0719 0746 0817 0851 0925 0959 1031 1101 1131 1201 1231 1301 1331 1401 1431 Sunderland, Holmeside arr 0721 0748 0819 0853 0927 1001 1033 1103 1133 1203 1233 1303 1333 1403 1433 Sunderland, Holmeside dep 0721 0748 0819 0854 0928 1002 1034 1104 1134 1204 1234 1304 1334 1404 1434 Sunderland Interchange arr Sunderland Interchange dep University, Chester Road Campus 0723 0750 0821 0856 0930 1004 1036 1106 1136 1206 1236 1306 1336 1406 1436 Sunderland Royal Hospital 0726 0753 0824 0859 0933 1007 1039 1109 1139 1209 1239 1309 1339 1409 1439 Sunderland Crematorium 0731 0758 0829 0904 0938 1012 1044 1114 1144 1214 1244 1314 1344 1414 1444 Pennywell, Shopping Centre 0734 0801 0832 0907 0941 1015 1047 1117 1147 1217 1247 1317 1347 1417 1447 Doxford International - Sunderland - Pennywell Go North East 39 Effective from: 05/09/2021 Monday to Friday (continued) Doxford International Admiral Way 1434 1508 1540 1610 1641 1711 1747 1824 1852 1923 ... -

PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW of SUNDERLAND Final

THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF SUNDERLAND Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in the City of Sunderland October 2003 SOUTH BENTS Sheet 2 of 3 Sheet 2 "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD03114G" 2 Abattoir 1 Monkwearmouth School Nine Wells S Gardens H I E N L EW D C S AS Allotment Gardens T R LE Seaburn Dene O RO AD A Primary School D Mere Knolls Cemetery 3 Whitburn Sands FULWELL WARD FULWELL S Refuse Tip E A (disused) L Seaburn A N Park N E Und Straight E W Nursing Home C A S T L E R Parson's O Fulwell School OAD Roker Cliff R A ER W Playing Field HEST Rocks D CHIC Park H Infant AD I EA RO T S C School H Primary U R School C H R D Primary School Hylton Red House School WITHERWACK DOWNHILL School E D Club M A SW O O R RT N E H O D N R T A O L A A R O L D A R Church N OAD H Y R CARLEY HILL S EMBLE C O W L T Carley Hill L L O Y O Primary School L N H D K M E Southwick I L R L Cemetery Playing Field R E O M A D SIDE CLIFF ROAD E AV OD WO F LE U AP L REDHILL WARD M W S E Allotment Gardens RE L C L Y E R RL MA O A D D A D O Roker Park OA R Maplewood R R N CA O ED S School R P M MARLEY POTS Carley Hill O H Cricket Ground T M OR AY D Schools ST ROKER DCAR ROA RE Monkwearmouth Schools Church College SOUTHWICK WARD Hospital WA SH ING TO N R AD O ON RO AD HYLT ORTH N -

COUNTY DURHAM a N 50 Gateshead L H

. D D T Scotswood W D S G E R D D ST. D O B E A W R R To — Carr N N E Nexus O W E S E B A L L A T E A L A N E M O G I Baltic HEBBURN 89 Monkton T D A TE G G Y R O O S U O O G S Jarrow and R A N Ellison O T D LAWRENCE I House R C Millennium R 88 O M S St. Anthony’s R Law T Hall A E N C Centre R K T NEW TOWN Hebburn K R A D N E Park 87 E R I A R R C W G O R R O For details of bus services E S Courts S Bridge LT M E A Park Lightfoot I E D T D N E G A 27 A N A T K E Y S O T L O D E W W N N R I A T in this area G O E E U S A L A A B A T O T K Adelaide D T T Q H N R E R S D see the C N O M O A E T T A R O HEBBURN E C E O A N ST. Y PO Newcastle guide Centre R T R D D B A S C N E Y PO G D Hebburn E E T A M B&Q L Q1 N L L S G A O D ’ ANTHONY’S I D I L S P N E V B L R O D A I T A R M D O H B S T R R R R W A O R S S N G A K Q1 93 E R O A D O E L S W I C I K S O D O E L R SAGE Q E R Newcastle W L G 94 A D U T ST. -

Three Five Four Three Two Two One Three

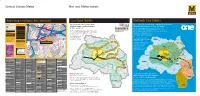

Central Station Metro Bus and Metro tickets Area map and local bus services Transfare tickets Network One tickets to St James’ Park to Monument Map Key Nexus E Nearest bus stops for 9 minutes T 8 minutes R Road served by bus S Are you making one journey using Are you travelling for one day or one week on different onward travel W A A Bus stop (destinations listed below) ES R H Stop Stop no. Stop code TG E ATE C Metro bus replacement R different types of public transport types of public transport in Tyne and Wear? ø A 08NC95 twramgmp OAD GS N T G I J Metro line B 08NC94 twrgtdtw O The Journal K A HN ST N L I National Rail line C 08NC93 twramgmj R in Tyne and Wear? For one day’s unlimited travel on all public transport in Tyne Theatre D T M G National Cycle Network (off-road) D D 08NC92 twramgmg D Alt. J S E Tyne and Wear*, buy a Day Rover from the ticket machine. Hadrian’s Wall Path E 08NC91 twramgmd R Dance U Newcastle P A Transfare ticket allows you to buy just one ticket W A Gallery W Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright 2015. P ES F T 08NC90 twramgma V City IN TGA E Arts Arena T E K E R for a journey that involves travelling on more than For one week’s travel on all public transport in Tyne and Wear*, G 08NC87 twramgjt E OA L LA D Metro bus R H 08NC86 twramgjp U T simply choose which zones you need S one type of transport – eg Metro and bus. -

Meadow Well Metro Station, Newcastle

Meadow Well Metro station Bus and Metro tickets Area map and local bus services Transfare tickets Network One tickets N EW B LY ENT R N CRESC Map Key A B Norham Community M D K A A R Are you making one journey using Are you travelling for one day or one week P O Ro a d se rv ed by b us Technology L A D TO R P K R A W N E O R Directio n of travel School N O N Y T E RD C P A R L E G E L 391 M A Bus stop (destin ation s listed below) V P different types of public transport L O O T on different types of public transport in P E R A 1A G C ES S V 1 U D W Metro bus replacement E N I N S ø O L N M N D K U C H G E V I R E E 310 M L Y Metr o line A A C in Tyne and Wear? H Tyne and Wear? L St Joseph's C K ' S Y E Y A E DG W3W3 O E E UE RI E U L FORD RC Primary L L National Cycle Network N N B L E S N AV E G A P O K IN P E DA K I IC Schooll V N R W ET U A H N R North Tynes ide Stea m Railway H L N E C ᵮ A AL G D A B A E N A N A Transfare ticket allows you to buy just one ticket For one day’s unlimited travel on all public transport in V I I M E VE K O F A A A R R Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright 2013. -

Street Book A

Street Book A Street Limits: Locality District Adoption ABBAY STREET DEAN TERRACE TO SOUTHWICK SUNDERLAND NORTH OF Adopted WESSINGTON WAY THEN RIVER WEAR EASTERLY TO to CUL DE SAC AT NORTHERN WAY ABBAY STREET EAST DEAN TERRACE to ABBAY SOUTHWICK SUNDERLAND NORTH OF Adopted BACK - DICKENS STREET RIVER WEAR STREET (SOUTHWICK) WEST BACK ABBAY STREET WEST DEAN TERRACE to SOUTHWICK SUNDERLAND NORTH OF Adopted BACK CLOCKWELL STREET RIVER WEAR ABBEY CLOSE Abbey Road WASHINGTON WASHINGTON Adopted VILLAGE ABBEY DRIVE Brinkburn Crescent to GRASSWELL HOUGHTON-LE-SPRING Adopted SEDGELETCH ROAD ABBEY ROAD Parkway to Village Lane WASHINGTON WASHINGTON Adopted VILLAGE ABBOTSFIELD CLOSE Bishops Way to CUL DE SAC CHAPELGARTH SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted RIVER WEAR ABBOTSFIELD CLOSE Bishops Way to CUL DE SAC DOXFORD PARK SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted RIVER WEAR ABBOTSFORD GROVE Beresford Park to ASHBROOKE SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF No record of Thornholme Road RIVER WEAR adoption Book A Update No. 10 01/08/2019 Version No 10 Page 1 of 46 Street Limits: Locality District Adoption ABBS STREET Southwick Road to Victoria MONKWEARMOU SUNDERLAND NORTH OF Adopted Terrace South TH RIVER WEAR ABERCORN ROAD Arbroath Road to Allendale THORNEY CLOSE SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted Road RIVER WEAR ABERDARE ROAD ALLENDALE ROAD to FARRINGDON SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted ASHWELL ROAD RIVER WEAR ABERDEEN TOWER TOWER BLOCK OF FLATS SILKSWORTH SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF No record of AT SOUTHERN PART OF RIVER WEAR adoption GILLEY LAW ESTATE ABERFORD DRIVE SUCCESS ROAD to SHINEY ROW HOUGHTON-LE-SPRING No record of AGINCOURT adoption ABINGDON STREET Chester Road to Cleveland THORNHILL SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted Road RIVER WEAR ABINGDON STREET CHESTER ROAD SOUTH BARNES SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted EAST BACK - BACK to EWESLEY ROAD RIVER WEAR EWESLEY ROAD WEST NORTH BACK BACK ABINGDON STREET CHESTER ROAD SOUTH BARNES SUNDERLAND SOUTH OF Adopted WEST BACK - BACK to EWESLEY ROAD RIVER WEAR BARNARD STREET NORTH BACK EAST BACK Book A Update No. -

Bus Diversions – Sunderland Tour Series Cycle Event Tuesday 10 August 2021 Stagecoach Services 3, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 18, 18A, 20, 23, E1, E2, E6, X24 & X24A

Bus Diversions – Sunderland Tour Series Cycle Event Tuesday 10 August 2021 Stagecoach Services 3, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 18, 18A, 20, 23, E1, E2, E6, X24 & X24A On Tuesday, 10 August 2021 from 3:00pm to 9:00pm to allow the Tour Series Cycle Event to take place in Sunderland, a number of road closures will be required, and bus services will be diverted. No buses will operate on Vine Place, Holmeside, Burdon Road, Toward Road, Fawcett St and John Street as a result of the event but will use either Park Lane interchange or temporary stops on St Marys Boulevard. The road closures are advised as being during the following periods: Burdon Road between 7:00am and 11:00pm Park Road between 2:00pm and 9:00pm Toward Road between 2:00pm and 9:00pm Borough Road between 3:00pm and 9:00pm Buses will depart from St Marys Boulevard Stagecoach 3, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 18, 18A, 20, 23, E1, E2 E6, X1, X24 and X24A. Temporary stops will show service numbers. Details of individual services: Stagecoach Service 3, 12 and 13 trips towards Wheatsheaf, between approx. 3:00pm and 9:00pm will divert from Priestman Roundabout via St. Michaels Way and St. Mary’s Boulevard to Wearmouth Bridge. Buses will observe a temporary eastbound bus stop on St. Mary’s Boulevard just to the west of the Cumberland Street junction, and will be unable to observe their Vine Place or Fawcett Street stops. Service 3, 12 and 13 trips towards Durham Road, between approx. -

Parish Registers in the Local Studies Centre

Sunderland Local Studies Parish Registers on Microfilm Films Supplied by Tyne And Wear Archives Service The dates given are the year of the earliest and latest register available. It does not mean there are no gaps in the coverage between these dates. Church of England Parishes All Saints, Eppleton Reels Number 1,2,3 Banns 1888-1960 Baptisms 1887-1943 Marriages 1888-1968 All Saints, Monkwearmouth Reels Number 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D, 3E, 3F, 3G,3H Banns 1916-1984 Baptisms 1849-1980 Burials 1851-1891 Marriages 1849-1980 All Saints, Penshaw Reels Number 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Banns 1754-1986 Baptisms 1754-1966 Burials 1754-1949 Burials 1949-1972 (new burial ground) Marriages 1754-1986 Christ Church, Bishopwearmouth Reels Number 11, 12, 172 Banns 1876-1979 Baptisms 1876-1970 Marriages 1876-1970 Baptisms 1876-1958, See St Thomas, Bishopwearmouth Marriages 1876-1933, See St Thomas, Bishopwearmouth Good Shepherd, Bishopwearmouth Reels Number 13, 26 Banns 1940-1976 See also, Holy Trinity, Sunderland Herrington Chapel Reel Number 14 (St. Cuthbert, West Herrington) Marriages 1841-1847 Holy Trinity, Southwick, Reels Number 15, 15A, 15B, 16, 17, 17A, 17B, 18, 18A, 18B Banns 1954-1993 Baptisms 1845-1997 Burials 1844-1988 Graves 1869-1884 Marriages 1846-1988 Holy Trinity, Sunderland Reels Number 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Banns 1756-1927 Baptisms 1719-1970 Burials 1719-1909 Marriages 1719-1973 Holy Trinity, Usworth Reels Number 44, 45, 46, 47 Banns 1948-1971 Baptism 1835-1942 Burials 1835-1943 Marriages 1835-1954 St. -

Runners and Riders

Local Government Election 2018 - Thursday 3 May 2018 The Candidates Standing at the above Election are listed below:- Ward Name of Candidate Description Address of Candidate Timothy Hanson ELLIS Liberal Democrat 6 Medway Gardens, High Barnes, Sunderland, SR4 8NJ Zaf IQBAL Labour Party 97 Stannington Grove, Sunderland, SR2 9EH Barnes Antony MULLEN The Conservative Party Candidate 30 Plains Road, Plains Farm, Sunderland, SR3 1SL Caroline Leigh ROBINSON Green Party candidate 26 Morval Close, Sunderland, SR3 2RS James Clark DOYLE The Conservative Party Candidate 20 Zion Terrace, Fulwell, Sunderland, SR5 1NE Rebecca Jane LAPPING Green Party candidate 11 Cranberry Square, Sunderland, SR5 3PH Castle Doris MACKNIGHT Labour and Co-operative Party 37 Barking Crescent, Town End Farm, Sunderland, SR5 4QZ Jack Thomas STOKER Liberal Democrat 29 Blackwood Road, Town End Farm, Sunderland, SR5 4PW Anthony ALLEN Independent 60 Edwin Street, Houghton-le-Spring, Tyne and Wear, DH5 8AP Jack Edward CUNNINGHAM Labour and Co-operative Party 50 Regent Street, Hetton-le-Hole, Tyne and Wear, DH5 9AA Copt Hill Esme Rose Stafford FEATHERSTONE Green Party candidate Flat 4, 3 Claremont Terrace, Sunderland, SR2 7LB Patricia Ann FRANCIS The Conservative Party Candidate 5 Baslow Gardens, Sunderland, SR3 1NA George Edward BROWN The Conservative Party Candidate 44 Sanford Court, Sunderland, SR2 7AU Elizabeth GIBSON Labour Party 62 Vicarage Close, New Silksworth, Sunderland, SR3 1JF Doxford Alan Michael David ROBINSON Green Party candidate 26 Morval Close, Sunderland, SR3 -

8 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8 bus time schedule & line map 8 East End - South Hylton View In Website Mode The 8 bus line (East End - South Hylton) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) East End: 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM (2) South Hylton: 7:03 PM - 11:03 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8 bus arriving. Direction: East End 8 bus Time Schedule 33 stops East End Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:19 AM - 10:34 PM Monday 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM Riverside Park, South Hylton Riverside Park, Sunderland Tuesday 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM High Street - Metro, South Hylton Wednesday 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM Hylton Bank-Greenbank Drive, South Hylton Thursday 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM Friday 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM Hylton Bank-Social Club, South Hylton East Grove, Sunderland Saturday 6:54 PM - 10:34 PM St Annes, Pennywell Grindon Lane, Sunderland Hylton Road-St Lukes Road, Pennywell 8 bus Info Direction: East End Hylton Road-Palgrove Road, Pennywell Stops: 33 Hylton Road, Sunderland Trip Duration: 28 min Line Summary: Riverside Park, South Hylton, High Hylton Road-Havelock Hospital, Hylton Lane Street - Metro, South Hylton, Hylton Bank-Greenbank Estate Drive, South Hylton, Hylton Bank-Social Club, South Hylton, St Annes, Pennywell, Hylton Road-St Lukes Havelock Council O∆ces, Hylton Lane Estate Road, Pennywell, Hylton Road-Palgrove Road, B1405, Sunderland Pennywell, Hylton Road-Havelock Hospital, Hylton Lane Estate, Havelock Council O∆ces, Hylton Lane Holborn Road-Hartford Road, Hylton Lane Estate Estate, Holborn -

PEC Services Practice Lists

Practice Name Address Phone Number 40 Craster Court, Manor Walks, Cramlington, Northumberland, A&G Marshall Optometrists Ltd NE23 6UT A. W. Winlow Opticians Ltd 2 St. Lukes Terrace, Sunderland, Tyne & Wear, SR4 6NQ Bellway House, Woodhorn Road , Ashington, Northumberland, AARON OPTOMETRISTS LTD NE63 0AE Ads Eye Clinic 19-23 Norton RoadStockton-on-tees 01642 676327 AG Wade Ltd t/a Wadeopticians Unit 1 , Parsons Drive, Ryton, Tyne and Wear, NE40 3RA Ashington Specsavers LTD 8 woodhorn road, ashington, Northumberland, NE63 9UX B Braysher Optometrists 23 The Precinct, Blaydon, Tyne and Wear, NE21 5BT Boots Opticians 247 High Street West, Sunderland, SR1 3DE Boots Opticians Unit 10, Manor Walks, Cramlington, NE23 6QW Boots Opticians 190 Whitley Road, Whitley Bay , Tyne and Wear, NE26 2TA Boots Opticians 7 Castlegate, Berwick-upon-tweed, Northumberland, TD15 1JS Boots Opticians 21 Bridge Street, MORPETH, Northumberland, NE61 1NT Boots Opticians 36/38 Bondgate Within, Alnwick, Northumberland, NE66 1JD 0191 374 0876 Boots Opticians Unit 9 Prince Bishops Shopping Centre, Durham, DH1 3UJ 01429 891291 Unit 137 Middleton Grange Shopping Centre, Hartlepool, County Boots Opticians Durham, TS24 7RZ 0191 415 3840 Boots Opticians T/a Darlington Eyecare 24a High Row,, Darlington, Durham, DL3 7QW Ltd Boots Opticians Unit 77 Albany Mall, The Galleries, Washington, NE38 7SD 0191 548 5015 Buckingham & Hickson Front Street, Stanhope, Durham, DL13 2TZ Buckingham and Hickson 290 Fulwell Road, Sunderland, SR6 9AP Buckingham and Hickson 26 Windsor Terrace, Grangetown,