A LIFE for MEN by E. J. Williams Memoir of a Non-Flying, Non

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 4 Insightinsight Issue 4

ISSUE 4 INSIGHTINSIGHT ISSUE 4 INSIGHTMAGAZINE 1 INSIGHT In this issue… ISSUE 4 2018 From the 09 39 SQUADRON CADET VISIT Editor… EDITORIAL TEAM: 10 Sqn Ldr Keith Bissett MSc BSc RAF. [email protected] External Email: 11 RAFA VISIT 23 20 Use personal email addresses listed Tel: +44 (0)1522 728377 12 NO. 56 SQUADRON EXERCISE Editor: 14 HIGH FLYING SUPPORTERS RECOGNISED Sqn Ldr Keith Bissett [email protected] A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A XIII SQN 17 REAPER PILOT Deputy Editor: Flt Lt D.J Hopkinson 18 RAF100 BATON RELAY AT RAF [email protected] WADDINGTON Welcome to this issue Artwork: 20 RAF100 FLYPAST of Insight. S. Oliver 23 RAF WADDINGTON’S 100 STATIONS IN Advertising by: 100 HOURS Welcome to this issue of the Insight Jo Marchant magazine; my final as editor of the Tel: 01536 526674 magazine before I handover to RAF WADDINGTON FRIENDS AND 24 FAMILIES DAY 18 24 Sqn Ldr Craig LeDieu. It has been an enjoyable experience bringing Designed by: community news to the Station over Amanda Robinson 26 51 SQUADRON HISTORY UNVEILED AT the last 2 years. [email protected] RAF WYTON In this edition we have news from 56 Published by: AWARDS Sqn and their freedom parade, the 28 Station Awards dinner and updates Lance Publishing Ltd, 1st Floor, Tailby House, from the many RAF100 events that Bath Road, Kettering, NN16 8NL 30 RUGBY LEAGUES happened in June & July. Tel: 01536 512624 Fax: 01536 515481 www.lancepublishing.co.uk 32 THE BATTLE OF THE BARGES As always we strive to include as [email protected] many articles as we can from our THE ISTAR FORCE AT THE ROYAL Station community. -

Magazine & Conservatories 01264 359355 Andover & North Hampshire Gazette Your Free Local Community Magazine – Reaching Approx

your ISSUE No. 124 local DECEMBER 2017 Windows, Doors Magazine & Conservatories 01264 359355 Andover & North Hampshire Gazette Your free local community magazine – Reaching approx. 45,000 readers every month All Makes Servicing Restoration, Paintwork, Light Crash Repairs, Engine Re-builds T: 01264 772416 M: 07525 421104 THRUXTON CLASSIC RESTORATION [email protected] (Independent Jaguar Specialist) Unit 13 Mayfield Industrial Est, Weyhill, Nr Andover, SP11 8HU + Full installation of wood burning Visit our stoves and fireplaces new + Wood based heating systems HETAS- registered + Central heating upgrades showroom + All plumbing and heating works at Walworth + Member of National Association Business of Chimney Sweeps Park 01264 310493 www.humphreyandcrockett.co.uk [email protected] Unit 11, Focus 303 Business Centre, Andover, Hampshire, SP10 5NY Online Advertising from as little as £10 per month Bespoke steelwork and ornamental fabrications – including For details contact Tracey on Balconies . Gates . Railings Tel: 01264-316499 Staircases . Balustrades . Garden Features Mob: 07775-927161 Obelisks from just £25 email: [email protected] Plant Support Hoops from £10 per pair Tulip and Narcissi Baskets £35 Plant Supports from just £8.50 per pair Hanging Basket Brackets from £8.50 Fire Pits from £50 Please contact us for your free We invite you to our Advent social with our exhibition of quilts made by our students no obligation quotation 16th, 19th and 20th December 2017 – SALE 30% on selected items. Our last working day this year will be Tel: 01264 737 747 22st Dec, we will re-open 3rd Jan 2018. Merry Christmas and happy New Year Web: www.boaengineering.co.uk to all our customers. -

Page Key to Index

PAGE KEY TO INDEX AIRCRAFT — B-17 "Flying Fortresses" 1 AIRCRAFT — Other 2 AWARDS — Military 2 AWARDS —Other 3 CITIES 3 ESCAPES and EVASIONS 10 GENERAL 10 INTERNEES 19 KILLED IN ACTION 19 MEMORIALS and CEMETERIES 20 MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS — 303rd BG 20 MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS — Other 21 MISSIONS — Target and Date 25 PERSONS 26 PRISONERS OF WAR 51 REUNIONS 51 WRITERS 52 1 El Screamo (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Miss Lace (Feb. 2004, pg. 18), (May 2004, Fast Worker II (May 2005, pg. 12) pg. 15) + (May 2005, pg. 12), (Nov. 2005, I N D E X FDR (May 2004, pg. 17) pg. 8) + (Nov. 2006, pg. 13) + (May 2007, FDR's Potato Peeler Kids (Feb. 2002, pg. pg. 16-photo) 15) + (May 2004, pg. 17) Miss Liberty (Aug. 2006, pg. 17) Flak Wolf (Aug. 2005, pg. 5), (Nov. 2005, Miss Umbriago (Aug 2003, pg. 15) AIRCRAFT pg. 18) Mugger, The (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flak Wolf II (May 2004, pg. 7) My Darling (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) B-17 "Flying Fortress" Floose (May 2004, pg. 4, 6-photo) Myasis Dragon (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flying Bison (Nov. 2006, pg. 19-photo) Nero (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flying Bitch (Aug. 2002, pg. 17) + (Feb. Neva, The Silver Lady (May 2005, pg. 15), “451" (Feb. 2002, pg. 17) 2004, pg. 18) (Aug. 2005, pg. 19) “546" (Feb. 2002, pg. 17) Fox for the F (Nov. 2004, pg. 7) Nine-O-Nine (May 2005, pg. 20) + (May 41-24577 (May 2002, pg. 12) Full House (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) 2007, pg. 20-photo) 41-24603 (Aug. -

Date Pilot Aircraft Serial No Station Location 6/1/1950 Eggert, Wayne W

DATE PILOT AIRCRAFT SERIAL_NO STATION LOCATION 6/1/1950 EGGERT, WAYNE W. XH-12B 46-216 BELL AIRCRAFT CORP, NY RANSIOMVILLE 3 MI N, NY 6/1/1950 LIEBACH, JOSEPH G. B-29 45-21697 WALKER AFB, NM ROSWELL AAF 14 MI ESE, NM 6/1/1950 LINDENMUTH, LESLIE L F-51D 44-74637 NELLIS AFB, NV NELLIS AFB, NV 6/1/1950 YEADEN, HUBERT N C-46A 41-12381 O'HARE IAP, IL O'HARE IAP 6/1/1950 SNOWDEN, LAIRD A T-7 41-21105 NEW CASTLE, DE ATTERBURY AFB 6/1/1950 BECKLEY, WILLIAM M T-6C 42-43949 RANDOLPH AFB, TX RANDOLPH AFB 6/1/1950 VAN FLEET, RAYMOND A T-6D 42-44454 KEESLER AFB, MS KEESLER AFB 6/2/1950 CRAWFORD, DAVID J. F-51D 44-84960 WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH WEST ALEXANDRIA 5 MI S, OH 6/2/1950 BONEY, LAWRENCE J. F-80C 47-589 ELMENDORF AAF, AK ELMENDORF AAF, AK 6/2/1950 SMITH, ROBERT G F-80B 45-8493 FURSTENFELDBRUCK AB, GER NURNBERG 6/2/1950 BEATY, ALBERT C F-86A 48-245 LANGLEY AFB, VA LANGLEY AFB 6/2/1950 CARTMILL, JOHN B F-86A 48-293 LANGLEY AFB, VA LANGLEY AFB 6/2/1950 HAUPT, FRED J F-86A 49-1026 KIRTLAND AFB, NM KIRTLAND AFB 6/2/1950 BROWN, JACK F F-86A 49-1158 OTIS AFB, MA 8 MI S TAMPA FL 6/3/1950 CAGLE, VICTOR W. C-45F 44-87105 TYNDALL FIELD, FL SHAW AAF, SC 6/3/1950 SCHOENBERGER, JAMES H T-7 43-33489 WOLD CHAMBERLIAN FIELD, MN WOLD CHAMBERLAIN FIELD 6/3/1950 BROOKS, RICHARD O T-6D 44-80945 RANDOLPH AFB, TX SHERMAN AFB 6/3/1950 FRASER, JAMES A B-50D 47-163 BOEING FIELD, SEATTLE WA BOEING FIELD 6/4/1950 SJULSTAD, LLOYD A F-51D 44-74997 HECTOR APT, ND HECTOR APT 6/4/1950 BUECHLER, THEODORE B F-80A 44-85153 NAHA AB, OKI 15 MI NE NAHA AB 6/4/1950 RITCHLEY, ANDREW J F-80A 44-85406 NAHA AB, OKI 15 MI NE NAHA AB 6/4/1950 WACKERMAN, ARNOLD G F-47D 45-49142 NIAGARA FALLS AFB, NY WESTCHESTER CAP 6/5/1950 MCCLURE, GRAVES C JR SNJ USN-27712 NAS ATLANTA, GA MACDILL AFB 6/5/1950 WEATHERMAN, VERNON R C-47A 43-16059 MCCHORD AFB, WA LOWRY AFB 6/5/1950 SOLEM, HERMAN S F-51D 45-11679 HECTOR APT, ND HECTOR APT 6/5/1950 EVEREST, FRANK K YF-93A 48-317 EDWARDS AFB, CA EDWARDS AFB 6/5/1950 RANKIN, WARNER F JR H-13B 48-800 WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB 6/6/1950 BLISS, GERALD B. -

Cat No Ref Title Author 3170 H3 an Airman's

Cat Ref Title Author OS Sqdn and other info No 3170 H3 An Airman's Outing "Contact" 1842 B2 History of 607 Sqn R Aux AF, County of 607 Sqn Association 607 RAAF 2898 B4 AAF (Army Air Forces) The Official Guide AAF 1465 G2 British Airship at War 1914-1918 (The) Abbott, P 2504 G2 British Airship at War 1914-1918 (The) Abbott, P 790 B3 Post War Yorkshire Airfields Abraham, Barry 2654 C3 On the Edge of Flight - Development and Absolon, E W Engineering of Aircraft 3307 H1 Looking Up At The Sky. 50 years flying with Adcock, Sid the RAF 1592 F1 Burning Blue: A New History of the Battle of Addison, P/Craig JA Britain (The) 942 F5 History of the German Night Fighter Force Aders, Gerbhard 1917-1945 2392 B1 From the Ground Up Adkin, F 462 A3 Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Aero Publishers' Staff 961 A1 Pictorial Review Aeroplane 1190 J5 Aeroplane 1993 Aeroplane 1191 J5 Aeroplane 1998 Aeroplane 1192 J5 Aeroplane 1992 Aeroplane 1193 J5 Aeroplane 1997 Aeroplane 1194 J5 Aeroplane 1994 Aeroplane 1195 J5 Aeroplane 1990 Aeroplane Cat Ref Title Author OS Sqdn and other info No 1196 J5 Aeroplane 1994 Aeroplane 1197 J5 Aeroplane 1989 Aeroplane 1198 J5 Aeroplane 1991 Aeroplane 1200 J5 Aeroplane 1995 Aeroplane 1201 J5 Aeroplane 1996 Aeroplane 1525 J5 Aeroplane 1974 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1526 J5 Aeroplane 1975 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1527 J5 Aeroplane 1976 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1528 J5 Aeroplane 1977 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1529 J5 Aeroplane 1978 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1530 J5 Aeroplane 1979 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1531 J5 Aeroplane 1980 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1532 J5 Aeroplane 1981 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1533 J5 -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

History, It Is Checkered

Historical Notes ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date: Mon, 3 Nov 1997 23:30:10 +0500 From: "Chuck Rippel" <crippel@...> Subject: [R-390] BA Receiver Fun - Targets Thanks for the many notes I received about posting some targets for our BA receivers. I was astounded at the number of affirmative replies received. As many know, I find listening a great deal of fun and very challenging. There are basically two styles of listening. Short Wave Listening is where the operator tunes in to a particular program. Short Wave Broadcast DX'ing is listening for very weak or seasonally challenging radio broadcasts or stations. In most cases, the language used by the broadcaster is not english as they are serving the local population. It is DX'ing v/s Listening where I intend to focus. Being a good SWBC DX'er is a bit like being a good detective. Various clues are pieced together to arrive at a conclusion. In our case, identifying an unknown station. Some of those clues are: Time Frequency Language Programming Music Style Time: Audibility of a station depends on the time it is broadcasting and the frequency it is on. Typically, the frequencies over 10 mhz are best during local day light and below, local dark. Signals below 7 mhz generally require darkness between the transmitter and receiver locations. However, not always and we will explore the opportunities when that rule can be expanded a bit. Frequency: Armed with the time and knowledge of propagation, frequency is the next big clue. There is general frequency consideration or band consideration. An example might be if a station on 4915 were being heard at 2200UTC on the East Coast. -

North Weald the North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 4

The Spirit of North Weald The North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 4 North Weald’s role during World War 2 Epping Forest District Council www.eppingforestdc.gov.uk North Weald Airfield Hawker Hurricane P2970 was flown by Geoffrey Page of 56 Squadron when he Airfield North Weald Museum was shot down into the Channel and badly burned on 12 August 1940. It was named ‘Little Willie’ and had a hand making a ‘V’ sign below the cockpit North Weald Airfield North Weald Museum North Weald at Badly damaged 151 Squadron Hurricane war 1939-45 A multinational effort led to the ultimate victory... On the day war was declared – 3 September 1939 – North Weald had two Hurricane squadrons on its strength. These were 56 and 151 Squadrons, 17 Squadron having departed for Debden the day before. They were joined by 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron’s Blenheim IF twin engined fighters groundcrew) occurred during the four month period from which flew in from RAF Hendon to take up their war station. July to October 1940. North Weald was bombed four times On 6 September tragedy struck when what was thought and suffered heavy damage, with houses in the village being destroyed as well. The Station Operations Record Book for the end of October 1940 where the last entry at the bottom of the page starts to describe the surprise attack on the to be a raid was picked up by the local radar station at Airfield by a formation of Messerschmitt Bf109s, which resulted in one pilot, four ground crew and a civilian being killed Canewdon. -

International Default Location Field the Country Column Displays The

Country Descr Country Descr AUS CAIRNS BEL KLEINE BROGEL AUS CANBERRA BEL LIEGE AUS DARWIN, NORTHERN BEL MONS TERRITOR Belgium BEL SHAPE/CHIEVRES AUS FREMANTLE International Default Location Field BEL ZAVENTEM AUS HOBART Australia BEL [OTHER] AUS MELBOURNE The Country column displays the most BLZ BELIZE CITY AUS PERTH commonly used name in the United States of BLZ BELMOPAN AUS RICHMOND, NSW Belize America for another country. The Description BLZ SAN PEDRO AUS SYDNEY column displays the Default Locations for Travel BLZ [OTHER] AUS WOOMERA AS Authorizations. BEN COTONOU AUS [OTHER] Benin BEN [OTHER] AUT GRAZ Country Descr Bermuda BMU BERMUDA AUT INNSBRUCK AFG KABUL (NON-US FACILITIES, Bhutan BTN BHUTAN AUT LINZ AFG KABUL Austria BOL COCHABAMBA AUT SALZBURG AFG MILITARY BASES IN KABUL BOL LA PAZ AUT VIENNA Afghanistan AFG MILITARY BASES NOT IN BOL SANTA CRUZ KABU AUT [OTHER] Bolivia BOL SUCRE AFG [OTHER] (NON-US FACILITIES AZE BAKU Azerbaijan BOL TARIJA AFG [OTHER] AZE [OTHER] BOL [OTHER] ALB TIRANA BHS ANDROS ISLAND (AUTEC & Albania OPB BIH MIL BASES IN SARAJEVO ALB [OTHER] BHS ANDROS ISLAND Bosnia and BIH MIL BASES NOT IN SARAJEVO DZA ALGIERS Herzegovina Algeria BHS ELEUTHERA ISLAND BIH SARAJEVO DZA [OTHER] BHS GRAND BAHAMA ISLAND BIH [OTHER] American Samoa ASM AMERICAN SAMOA BHS GREAT EXUMA ISL - OPBAT BWA FRANCISTOWN Andorra AND ANDORRA Bahamas SI BWA GABORONE AGO LUANDA BHS GREAT INAGUA ISL - OPBAT Angola Botswana BWA KASANE AGO [OTHER] S BWA SELEBI PHIKWE ATA ANTARCTICA REGION POSTS BHS NASSAU BWA [OTHER] Antarctica ATA MCMURDO STATION -

Baz the Biography of Squadron Leader Ian Willoughby Bazalgette VC DFC

www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca “His courage and devotion to duty were beyond praise” www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca Bomber Command Museum of Canada Nanton, Alberta, Canada www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca Baz The biography of Squadron Leader Ian Willoughby Bazalgette VC DFC www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca Dave Birrell For Baz, W/C D. Stewart Robertson DFC, and all the others who served with Bomber Command during the Second World War. Copyright 2018 by Dave Birrell. All rights reserved. To reproduce anything in this book in any manner, permission must first be obtained from the Nanton Lancaster Society. First Edition (1996) Second Edition (2009) Third Edition (2014) Fourth Edition (2018) Published by The Nanton Lancaster Society Box 1051 Nanton, Alberta, Canada; T0L 1R0 www.bombercommandmuseum.ca The Nanton Lancaster Society is a non-profit, volunteer- driven society which is registered with Revenue Canada as a charitable organization. Formed in 1986, the Society has the goals of honouring all those associated with Bomber Command and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. The Society established and operates the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta which is located 75 kilometres south of Calgary. www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca ISBN 978-0-9880839-1-2 Front cover: “Beyond Praise” by Len Krenzler (S/L Bazalgette is buried in the churchyard, just beyond the yellow flowers.); Portrait courtesy Royal Canadian Military Institute Back cover: Portrait by Patrick McNorgan CONTENTS Introduction to the Third Edition 7 Foreword 9 Prologue 13 1. The Pre-war Years 15 2. 51st Searchlight Regiment 29 3. Training in the Royal Air Force 37 4. -

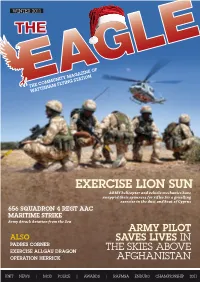

Exercise Lion

WINTER 2011 Station ying THE COMMUNITY MAGAZINE OF WATTISHAM FL EXERcise Lion sun ARMY helicopter and vehicle mechanics have swapped their spanners for rifles for a gruelling exercise in the dust and heat of Cyprus 656 SQuaDRon 4 Regt aac MARitime stRIKE Army Attack Aviation from the Sea ARmy piLot ALso saVes LIVes in PADRes coRneR EXERcise ALLgau DRagon the SKieS ABOVE OpeRation HERRicK AfGHAniSTAN Unit NewS | MOD POLICE | AWArdS | RAFMSA ENDURO CHAMPIONSHIP 2011 THE EAGle CONTENTS THE EAGle CONTENTS 3 2 From the Editor: Lt Col (Retd) RW SILK MBE Station Staff Officer elcome to the winter (Christmas) edition of The Eagle, which again covers operations, W training and a host of other activities back at Wattisham, our Home Base. You will see from the Station 2 Commander’s introduction that the past few months have been somewhat hectic with all kinds of activities, which has pushed the station very much into the media spotlight. Of course on the downside the Station Commander, Col Neale Moss, is preparing to leave us to be replaced by Col Andy Cash in the New Year. I will not dwell on this at the moment as the various reports of the ‘Governor’’ leaving will be carried in the next edition. Finally, the editorial team wishes all our readers a peaceful Christmas and the very best of fortune in the New Year. 30 06 I Foreword 26 I 7 Air Assault Battalion REME 36 I Welfare Matters Introduction by Colonel Neale Moss News and updates from 7 Air Assault News and updates from the various Unit OBE, AH Force Commander, Wattisham Battalion REME, including Exercises Lion Welfare Offices. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible.