Somalis in Oslo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADMISSION DOCUMENT Nortel AS Admission to Trading of Ordinary

ADMISSION DOCUMENT Nortel AS A private limited liability company incorporated under the laws of Norway, registered no. 922 425 442. Admission to trading of ordinary shares on Merkur Market This admission document (the Admission Document) has been prepared by Nortel AS (the Company or Nortel and, together with its consolidated subsidiaries, each being a Group Company, the Group) solely for use in connection with the admission to trading (the Admission) of the Company’s 14,416,492 shares, each with a par value of NOK 0.01 (the Shares) on Merkur Market. The Company’s Shares have been admitted for trading on Merkur Market and it is expected that the Shares will start trading on 18 November 2020 under the ticker symbol “NTEL-ME”. The Shares are, and will continue to be, registered with the Norwegian Central Securities Depository (VPS) in book-entry form. All of the issued Shares rank pari passu with one another and each Share carries one vote. Merkur Market is a multilateral trading facility operated by Oslo Børs ASA. Merkur Market is subject to the rules in the Securities Trading Act and the Securities Trading Regulations that apply to such marketplaces. These rules apply to companies admitted to trading on Merkur Market, as do the marketplace’s own rules, which are less comprehensive than the rules and regulations that apply to companies listed on Oslo Børs and Oslo Axess. Merkur Market is not a regulated market. Investors should take this into account when making investment decisions THIS ADMISSION DOCUMENT SERVES AS AN ADMISSION DOCUMENT ONLY, AS REQUIRED BY THE MERKUR MARKET ADMISSION RULES. -

Spm Og Svar Pakke 8.Xlsx

Spørsmål og svar nr. 2 - 18.12.2015 Rutepakke 8 Nr dato Spørsmål Svar 1 02.12.2015 Vi ønsker i utgangspunktet å gi tilbud på begge rutepakkene Frist for innlevering utsettes til 26.02.2015 kl som er ute i Møre og Romsdal nå. Samtidig er det et svært 12:00. omfattende arbeid for en ny operatør å sette seg inn i to nye ruteområder, og vi ser at det med tiden vi har til rådighet her, særlig med tanke på at det er jul i anbudsfasen, blir meget vanskelig å gi konkurransedyktige tilbud på to ruteområder. Vi anmoder derfor oppdragsgiver til å utsette innleveringsfristen med to uker, til 26.02.2015. 2 03.12.2015 Kan vi få tilgjengelig ansattopplysninger og prisskjema ? Del 5.1 Prisskjema legges ut på mercell. Ansattopplysninger sendes ut på forespørsel så snart vi har disse oppdatert fra dagens operatører. 3 04.12.2015 Del 4.3 Hvis mulig er det ønskelig at det sendes ut pattern i Excel Pattern‐print legges ut i Excel‐format. format. 4 04.12.2015 Del 4.4 Av rutetabellene for Fræna ser vi at det er store Viser til Del 1 Kontraktsvilkår, punkt 14 Endring endringer som vi er usikker på om kan opprettholdes i hele av oppdraget. kontraktsperioden. 5 04.12.2015 Kjøretidene fra Molde til Elnesvågen skolesenter er satt til 25 Det er satt opp en stiv rutetabell, der tiden ikke min. dette blir slik vi ser det, for liten tid og i rushtiden betydelig er justert for rushtrafikk. Det er noe for lite. Det ser heller ikke ut til å være tid til å hente busspakker. -

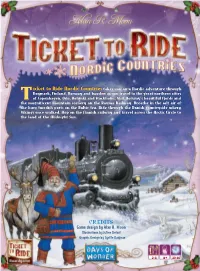

Rules EN 2015 TTR2 Rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2

[T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2 icket to Ride Nordic Countries takes you on a Nordic adventure through Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden as you travel to the great northern cities T of Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki and Stockholm. Visit Norway's beautiful fjords and the magnificent mountain scenery on the Rauma Railway. Breathe in the salt air of the busy Swedish ports on the Baltic Sea. Ride through the Danish countryside where Vikings once walked. Hop-on the Finnish railway and travel across the Arctic Circle to the land of the Midnight Sun. CREDITS Game design by Alan R. Moon Illustrations by Julien Delval Graphic Design by Cyrille Daujean 2-3 8+ 30-60’ [T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:52 Page3 Components 1 Globetrotter Bonus card u 1 Board map of Scandinavian train routes for the most completed tickets u 120 Colored Train cars (40 each in 3 different colors, plus a few spare) 46 Destination u 157 Illustrated cards: Ticket cards 110 Train cards : 12 of each color, plus 14 Locomotives ∫ ∂ u 3 Wooden Scoring Markers (1 for each player matching the train colors) u 1 Rules booklet Setting up the Game Place the board map in the center of the table. Each player takes a set of 40 Colored Train Cars along with its matching Scoring Marker. Each player places his Scoring Marker on the starting π location next to the 100 number ∂ on the Scoring Track running along the map's border. Throughout the game, each time a player scores points, he will advance his marker accordingly. -

Church and Health Grafisk/Trykk: BK.No • Foto: Shutterstock • Papir: Galeriepapir: Art Silk • Shutterstock Foto: Grafisk/Trykk: • BK.No CHURCH and HEALTH

XXX ChurCh and health Grafisk/trykk: BK.no • Foto: Shutterstock • Papir: GaleriePapir: Art Silk • Shutterstock Foto: Grafisk/trykk: • BK.no CHURCH AND HEALTH Contents 1. Introduction . .5 1.1 Background for the document presented at the General Synod 2015 .............................................................5 1.2 Overview of the content of the document ...........................................................................................................7 1.3 What do we understand by health?.......................................................................................................................8 2. 2. Theological Perspectives on Health and the Health Mission of the Church . 10. 2.1 Health in a biblical perspective............................................................................................................................10 2.2 Healing in a biblical perspective..........................................................................................................................12 2.3 The mission of the disciples . .15 2.4 The healing ministry of the Church....................................................................................................................16 3. Todays Situation as Context for the Health Mission of the Church . 19. 3.1 The welfare state as frame for the health mission of the Church ....................................................................19 3.2 Health- and care services under pressure ..........................................................................................................21 -

Performing History Studies in Theatre History & Culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY

Performing history studies in theatre history & culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY theatrical representations of the past in contemporary theatre Freddie Rokem University of Iowa Press Iowa City University of Iowa Press, Library of Congress Iowa City 52242 Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2000 by the Rokem, Freddie, 1945– University of Iowa Press Performing history: theatrical All rights reserved representations of the past in Printed in the contemporary theatre / by Freddie United States of America Rokem. Design by Richard Hendel p. cm.—(Studies in theatre http://www.uiowa.edu/~uipress history and culture) No part of this book may be repro- Includes bibliographical references duced or used in any form or by any and index. means, without permission in writing isbn 0-87745-737-5 (cloth) from the publisher. All reasonable steps 1. Historical drama—20th have been taken to contact copyright century—History and criticism. holders of material used in this book. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), The publisher would be pleased to make in literature. 3. France—His- suitable arrangements with any whom tory—Revolution, 1789–1799— it has not been possible to reach. Literature and the revolution. I. Title. II. Series. The publication of this book was generously supported by the pn1879.h65r65 2000 University of Iowa Foundation. 809.2Ј9358—dc21 00-039248 Printed on acid-free paper 00 01 02 03 04 c 54321 for naama & ariel, and in memory of amitai contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 1 Refractions of the Shoah on Israeli Stages: -

Opplevelseskartgrorud

OPPLEVELSESKART GRORUD–ellingsrUD Alna, grønnstruktur, idrett og kulturmiljø 1 Spesielle natur- og kulturmiljøer ALNA, HØLALØKKA OG ALNAPARKEN Alna er en del av Alnavassdraget, som er 17 km langt og et av Oslos 10 vassdrag. Vassdraget er omkranset av frodig og rik vegetasjon, med gode leveområder for dyr, fugler og planter. Langs vassdraget har man funnet 10 patte- dyrarter, 57 fuglearter, 2 amfibiearter, 370 kar- planter og 400 sopparter. Alnas hovedkilde er Alnsjøen i Lillomarka. Hølaløkka ble opparbeidet i 2004 med gjenåpning av Alnaelva og en dam. Økologiske prinsipper er lagt til grunn for utforming av prosjektet med stedegne arter, oppbygning av kantsoner og rensing av overvann. Alnaparken ble etablert i 1998 og er utviklet med mange aktivitetsmuligheter. GRORUDDAMMEN OG TIDLIG Området inneholder bl.a. turveier, to fotball- INDUSTRIVIRKSOMHET baner, sandvolleyballbane, frisbeegolfbane, Alnavassdraget var avgjørende for industri- ridesenter og en dam med amfibier. Området utviklingen på Grorud. I 1867 ble Lerfossen har mange forskjellige vegetasjonstyper, blant Klædefabrikk anlagt ved fossen av samme navn. annet en del gråor- og heggeskog. Enkelte Virksomheten skiftet siden navn til Grorud sjeldne sopparter er funnet i området. Klædefabrikk, og deretter Grorud Textilfabrikker. Groruddammen ble anlagt i 1870-årene som en del av industrianlegget. Like ved demningen ligger en tidligere shoddyfabrikk som drev gjen- vinning av ullmateriale fra opprevne ullfiller. Fabrikkbygningen står fremdeles, men har fått et nyere tilbygg mot turveien. Groruddammen er i dag et viktig friluftsområde som skal oppgraderes gjennom Groruddalssatsingen. 2 GAMLE GRORUD Fra 1830–40 årene startet uttak av Nordmarkitten, best kjent som Grorudgranitt. Fra 1870-årene ble dette en vesentlig arbeidsplass i Groruddalen, og ga sammen med annen industrivirksomhet og nærheten til jernbanestasjonen, grunnlag for lokalsamfunnet Grorud. -

NEW Media Document.Indd

MEDIA RELEASE WICKED is coming to Australia. The hottest musical in the world will open in Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in July 2008. With combined box office sales of $US 1/2 billion, WICKED is already one of the most successful shows in theatre history. WICKED opened on Broadway in October 2003. Since then over two and a half million people have seen WICKED in New York and just over another two million have seen the North American touring production. The smash-hit musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Pippin, Academy Award-winner for Pocahontas and The Prince of Egypt) and book by Winnie Holzman (My So Called Life, Once And Again and thirtysomething) is based on the best-selling novel by Gregory Maguire. WICKED is produced by Marc Platt, Universal Pictures, The Araca Group, Jon B. Platt and David Stone. ‘We’re delighted that Melbourne is now set to follow WICKED productions in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, the North American tour and London’s West End,’ Marc Platt and David Stone said in a joint statement from New York. ‘Melbourne will join new productions springing up around the world over the next 16 months, and we’re absolutely sure that Aussies – and international visitors to Melbourne – will be just as enchanted by WICKED as the audiences are in America and England.’ WICKED will premiere in Tokyo in June; Stuttgart in November; Melbourne in July 2008; and Amsterdam in 2008. Winner of 15 major awards including the Grammy Award and three Tony Awards, WICKED is the untold story of the witches of Oz. -

Styret I 2019 Har Bestått Av: Leder: Tor Erik Aarstad Nestleder: Mareno Nauste Kasserer: Bjørn Cameron Alexander Sekretær: Tone Kvamsås Styremedlem: Harry Hestad 1

Styret i 2019 har bestått av: Leder: Tor Erik Aarstad Nestleder: Mareno Nauste Kasserer: Bjørn Cameron Alexander Sekretær: Tone Kvamsås Styremedlem: Harry Hestad 1. vara: Ellen Undset 2. vara: Berit Torjuul Styret hadde i 2019 4 styremøter samt årsmøte 21. mars. Medlemstallet i 2019 var 117 medlemmer, som er en liten økning fra 2018. Av disse var 27 under 16 år. Vi er fremdeles langt unna tallene vi såg før vi måtte legge om til innmelding via minidrett da vi hadde nærmere 200 medlemmer. Det ble som vanlig arrangert klubbkveld i november med premiering av skitrimmen, fjelltrimmen og sykkeltrimmen. Vinner av Sucom trimmen ble og kunngjort her. Eresfjord IL var også i år med i «Prosjekt Tilhørighet» Vi hadde som vanlig 10 sesongkort fra MFK. Tross gratis utdeling til våre medlemmer, var det liten etterspørsel. Eresfjord IL har og ansvaret for vedlikeholdet av fotballbanen, her har banekomiteen lagt ned mange timer for å holde banen i god stand. Kom deg ut dagen 3/2-2019: Eresfjord og Vistdal skisenter. I samarbeid med Den Norske Turistforening og Vistdal IL arrangerte vi «kom deg ut dagen» i lysløypa Et vellykket arrangement med ca. 150 deltagere. Det var rebusløp, aking, skileik og grilling samt salg av kaker. Idrettslagene spanderte saft og kaffe. Innebandy: Fast spilling på søndager kl. 20.00 som vanlig.. det er mellom 6-12 spillere som møtes. Vi starter "sesongen" i august/ september etter skoleferien og holder på fram til slutten av juni. Startet på slutten av året med innebandy for jenter 8-12 år som et prøveprosjekt. Oppmøte er ca. -

Bestemmelser

INTERKOMMUNAL KOMMUNEDELPLAN FOR SJØOMRÅDENE PÅ NORDMØRE For kommunene Kristiansund, Tingvoll, Halsa, Smøla, Eide, Averøy, Sunndal, Surnadal, Aure, Gjemnes + Nesset kommune i Romsdal. Kortnavn: «Sjøområdeplan Nordmøre» BESTEMMELSER Aure Averøy Eide Gjemnes Halsa Kristiansund Nesset Smøla Sunndal Surnadal Tingvoll Revidert til godkjenning 03.04.2018 Side 1 av 7 INTERKOMMUNAL KOMMUNEDELPLAN FOR SJØOMRÅDENE PÅ NORDMØRE 1 PLANENS RETTSVIRKNING Sjøområdeplanen fastsetter fremtidig arealbruk og er bindende for nye tiltak eller utvidelse av eksisterende tiltak innenfor planområdet i de 11 kommunene: Aure, Averøy, Eide, Gjemnes, Halsa, Kristiansund, Nesset, Smøla, Sunndal, Surnadal og Tingvoll. Planen dekker sjøområdene i de deltakende kommunene (deler av Nesset kommune) og gjelder på vannflaten, i vannsøylen og på sjøbunnen. Plangrensen mot land går ved midlere høyvann og er definert ved "generalisert felles kystkontur" som er en kystkontur utarbeidet av Kartverket. Tidligere vedtatte reguleringsplaner skal fortsatt gjelde etter vedtak av sjøområdeplanen. Bestemmelser er knyttet til plankartet, klargjør vilkårene for bruk og vern av arealene og er juridisk bindende jfr. PBL §§ 11-9 til 11-11. Bestemmelser er vist med farget bakgrunn (grå). Øvrig tekst i bestemmelsene er retningslinjer eller av opplysende karakter. Bruk av planen skal sikre åpenhet, forutsigbarhet og medvirkning for alle berørte interesser og myndigheter. Det skal legges vekt på langsiktige løsninger, og konsekvenser for miljø og samfunn skal beskrives. I denne planen er det benyttet følgende bokstavkode: V: sosikode 6001 «Bruk og vern av sjø og vassdrag med tilhørende strandsone», for alle områder der det ikke tillates akvakultur. VKA: sosikode 6800 «Kombinerte formål i sjø og vassdrag med eller uten tilhørende strandsone», der det tillates akvakultur. Innenfor dette området er Akvakultur gitt fortrinnsrett dersom det etter søknad er gitt nødvendige tillatelser etter annet lovverk. -

Norway's Efforts to Electrify Transportation

Rolling the snowball: Norway’s efforts to electrify transportation Nathan Lemphers Environmental Governance Lab Working Paper 2019-2 Rolling the snowball: Norway’s efforts to electrify transportation EGL Working Paper 2019-2 September 2019 Nathan Lemphers, Research Associate Environmental Governance Lab Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy University of Toronto [email protected] Norway’s policies to encourage electric vehicle (EV) adoption have been highly successful. In 2017, 39 per cent of all new car sales in Norway were all-electric or hybrid, making it the world’s most advanced market for electric vehicles (IEA 2018). This high rate of EV ownership is the result of 30 years of EV policies, Norway’s particular political economy, and significant improvements in EV and battery technology. This paper argues that Norway’s sustained EV policy interventions are not only starting to decarbonize personal transportation but also spurring innovative electrification efforts in other sectors such as maritime transport and short- haul aviation. To explain this pattern of scaling, the paper employs Bernstein and Hoffmann’s (2018) framework on policy pathways towards decarbonization. It finds political causal mechanisms of capacity building and normalization helped create a welcoming domestic environment to realize early uptake and scaling of electric vehicles, and subsequently fostered secondary scaling in other modes of transportation. The initial scaling was facilitated by Norway’s unique political economy. Ironically, Norway’s climate leadership is, in part, because of its desire to sustain oil and gas development. This desire steered the emission mitigation focus towards sectors of the economy that are less contentious and lack opposing incumbents. -

Arguments for Basic Income, Universal Pensions and Universal

Money for nothing? Arguments for basic income, universal pensions and universal child benefits in Norway Christian Petersen Master thesis Department of Comparative Politics University of Bergen June 2014 Abstract Basic income is a radical idea which has gained more attention in many countries in recent years, as traditional welfare states are having trouble solving the problems they were created to solve. Basic income promises to solve many of these problems in an effective and simple way. The purpose of this thesis is to study basic income in a way which can supplement the existing literature, and make it relevant in a Norwegian perspective. Hopefully this can contribute towards placing basic income on the political agenda and in the public debate. A large amount of literature is written on basic income, but by comparing the arguments used to promote a basic income with empirical data from previously implemented social policy in Norway, I hope to contribute towards an area which is not well covered. To do this I identify the arguments used to promote a basic income, and compare them to the arguments used to promote other universal social policy in Norway at the time they were introduced. The empirical cases of the universal child benefit and the universal old age pension in Norway has been chosen, because they resemble a basic income in many ways. The study is of a qualitative nature, and the method of document analysis is used to conduct the study. The data material for basic income is mainly scholarly literature. The data materials used for the analysis of the child benefit scheme and the old age pension are government documents, mainly preparatory work for new laws, legal propositions put forward in parliament, white papers, and transcripts of debates in parliament. -

Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries

POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES POWER, COMMUNICATION, POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES The Nordic countries are stable democracies with solid infrastructures for political dia- logue and negotiations. However, both the “Nordic model” and Nordic media systems are under pressure as the conditions for political communication change – not least due to weakened political parties and the widespread use of digital communication media. In this anthology, the similarities and differences in political communication across the Nordic countries are studied. Traditional corporatist mechanisms in the Nordic countries are increasingly challenged by professionals, such as lobbyists, a development that has consequences for the processes and forms of political communication. Populist polit- ical parties have increased their media presence and political influence, whereas the news media have lost readers, viewers, listeners, and advertisers. These developments influence societal power relations and restructure the ways in which political actors • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, & Lars Nord • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard communicate about political issues. This book is a key reference for all who are interested in current trends and develop- ments in the Nordic countries. The editors, Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, and Lars Nord, have published extensively on political communication, and the authors are all scholars based in the Nordic countries with specialist knowledge in their fields. Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Nordicom is a centre for Nordic media research at the University of Gothenburg, Nordicomsupported is a bycentre the Nordic for CouncilNordic of mediaMinisters. research at the University of Gothenburg, supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers.