As Argued in the Introduction, This Collection Had Two Main Aims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista Distribuidores Correccion

• 12 Yard Productions • Alex Bowen Producciones • 2929 Entertainment • All3media International • 3DD Enterteinment • Allegro Pictures • 9 Story Enterprises • Alley Cat Films • A&E Channel Home Video • Alliance Atlantos Releasing • Aardman • Alphablocks Limited • Abduction Films • Altadena Film • Acacia • AMC Networks (Walking Dead Only) • ACC Action Concept Cinema • American Cinema Independent • ACI • American Portrait Films • Acorn Group • Andrea Films • Acorn Media • Andres Wood Producciones • Actaeon Films • Anglia Television • Action Concept • Animal Planet Video • Action Concept • Animalia Productions • Action Concept Film and Stuntproduktion • Annapurna Productions • Action Image • Apollo Media Filmmanagement • Adness Entertainment • Arte France • After Dark Films • Artemis Films • Ager Film • Associated Television • AIM Group • Athena • Akkord Film Produktion • Atlantic 2000 • Alain Siritzky Productions • Atlantic Productions • Alameda Films • August Entertaiment • Alcine Pictures • AV Pictures • Alcon Entertainment • AWOL Animation • Berlin Amimation Film • Best Film and Video • Best Picture Show • Betty TV • B & B Company • Beyond International • Baby Cow Productions • Big Bright House of Tunes • Bandai Visual • Big Idea Entertainment • Banjiay Internartional • Big Light Productions • Bankside Films • Big Talk Productions • Bard Entertainment • Billy Graham Evangelistic Association / World Wide • Bardel Distribution • Pictures • BBC Worldwide • Bio Channel • BBL Distribution • BKN International • BBP Music Publishing c/o Black -

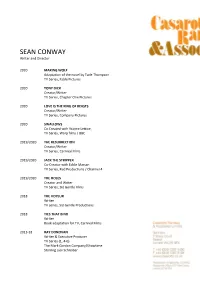

SEAN CONWAY Writer and Director

SEAN CONWAY Writer and Director 2020 MAKING WOLF Adaptation of the novel by Tade Thompson TV Series, Fable Pictures 2020 TONY DICK Creator/Writer TV Series, Chapter One Pictures 2020 LOVE IS THE KING OF BEASTS Creator/Writer TV Series, Company Pictures 2020 SWALLOWS Co Created with Wayne Lettice, TV Series, Warp films / BBC 2019/2020 THE RESURRECTION Creator/Writer TV Series, Carnival Films 2019/2020 JACK THE STRIPPER Co-Creator with Eddie Marsan TV Series, Red Productions / Channel 4 2019/2020 THE HOLES Creator and Writer TV Series, Sid Gentle Films 2018 THE VOYEUR Writer TV series, Sid Gentle Productions 2018 TIES THAT BIND Writer Book adaptation for TV, Carnival Films 2013-18 RAY DONOVAN Writer & Executive Producer TV Series (1, 4-6) The Mark Gordon Company/Showtime Starring Liev Schreiber 2016 ALL I SEE IS YOU Written with Marc Foster Feature Film 2DUX2/Sierra Affinity Starring Blake Lively and Danny Huston 2016 RED LIGHT BALLET Writer TV Pilot for 20th Century Fox 2015 LONG AFTER TONIGHT Writer Feature Film Hook Pictures & Creative England 2014 THE DESERVERS Writer & Co-Creator with Paul Abbott TV Series BBC 2014 DEAD I MAY WELL BE Writer TV Pilot for Anonymous Content 2014 SHAMELESS Writer 1 episode for series 10 Company/Channel 4 2011 HIT & MISS Writer 6 episodes of TV series for Sky / Red Productions / Abbott Vision, created by Paul Abbott and commissioned by Sky Atlantic Winner, Best European and International Fiction at the Television Festival de la Rochelle Nominated for Best Script Writer, 2012 RTS North West Awards Nominated -

Uk Producers in Cannes 2009

UK PRODUCERS IN CANNES 2009 Produced by Export Development www.ukfilmcouncil.org/exportteam The UK Film Council The UK Film Council is the Government-backed lead agency for film in the UK ensuring the economic, cultural and educational aspects of films are effectively represented at home and abroad. Our goal is to help make the UK a global hub for film in the digital age, with the world’s most imaginative, diverse and vibrant film culture, underpinned by a flourishing, competitive film industry. We invest Government grant-in-aid and Lottery money in developing new filmmakers, in funding new British films and in getting a wider choice of films to audiences throughout the UK. We also invest in skills training, promoting Britain as an international filmmaking location and in raising the profile of British films abroad. The UK Film Council Export Development team Our Export Development team supports the export of UK films and talent and services internationally in a number of different ways: Promoting a clear export strategy Consulting and working with industry and government Undertaking export research Supporting export development schemes and projects Providing export information The team is located within the UK Film Council’s Production Finance Division and is part of the International Group. Over the forthcoming year, Export Development will be delivering umbrella stands at the Toronto International Film Festival and Hong Kong Filmart; and supporting the UK stands at the Pusan Asian Film Market; American Film Market and the European Film Market, Berlin;. The team will also be leading Research & Development delegations to Japan and China. -

UK Film Council Group and Lottery Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 March 2011

UK Film Council Group and Lottery Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2011 HC 1391 SG/2011/142 £20.75 UK Film Council Group and Lottery Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2011 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 34(3) and 35(5) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 (as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998 and the National Lottery Act 2006) ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 14 JULY 2011 Presented to the Scottish Parliament pursuant to the Scotland Act 1998 Section 88 Company no: 3815052 London: The Stationery Office HC 1391 SG/2011/142 14 July 2011 £20.75 1 © UK Film Council (2011) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as UK Film Councilcopyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s website at: http://www.transparency.culture.gov.uk/arms-length-bodies/ ISBN: 9780102974485 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID: 2441293 07/11 13762 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre -

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS in 2016: Winners in *BOLD

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS IN 2016: Winners in *BOLD SPECIAL AWARD *NINA GOLD BREAKTHROUGH TALENT sponsored by Sara Putt Associates DC MOORE (Writer) Not Safe for Work- Clerkenwell Films/Channel 4 GUILLEM MORALES (Director) Inside No. 9 - The 12 Days of Christine - BBC Productions/BBC Two MARCUS PLOWRIGHT (Director) Muslim Drag Queens - Swan films/Channel 4 *MICHAELA COEL (Writer) Chewing Gum - Retort/E4 COSTUME DESIGN sponsored by Mad Dog Casting BARBARA KIDD Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell - Cuba Pictures/Feel Films/BBC One *FOTINI DIMOU The Dresser - Playground Television UK Limited, Sonia Friedman Productions, Altus Productions, Prescience/BBC Two JOANNA EATWELL Wolf Hall - Playground Entertainment, Company Pictures/BBC Two MARIANNE AGERTOFT Poldark - Mammoth Screen Limited/BBC One DIGITAL CREATIVITY ATHENA WITTER, BARRY HAYTER, TERESA PEGRUM, LIAM DALLEY I'm A Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! - ITV Consumer Ltd *DEVELOPMENT TEAM Humans - Persona Synthetics - Channel 4, 4creative, OMD, Microsoft, Fuse, Rocket, Supernatural GABRIEL BISSET-SMITH, RACHEL DE-LAHAY, KENNY EMSON, ED SELLEK The Last Hours of Laura K - BBC MIKE SMITH, FELIX RENICKS, KIERON BRYAN, HARRY HORTON Two Billion Miles - ITN DIRECTOR: FACTUAL ADAM JESSEL Professor Green: Suicide and Me - Antidote Productions/Globe Productions/BBC Three *DAVE NATH The Murder Detectives - Films of Record/Channel 4 JAMES NEWTON The Detectives - Minnow Films/BBC Two URSULA MACFARLANE Charlie Hebdo: Three Days That Shook Paris - Films of Record/More4 DIRECTOR: FICTION sponsored -

Independent Television Producers in England

Negotiating Dependence: Independent Television Producers in England Karl Rawstrone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol November 2020 77,900 words. Abstract The thesis analyses the independent television production sector focusing on the role of the producer. At its centre are four in-depth case studies which investigate the practices and contexts of the independent television producer in four different production cultures. The sample consists of a small self-owned company, a medium- sized family-owned company, a broadcaster-owned company and an independent- corporate partnership. The thesis contextualises these case studies through a history of four critical conjunctures in which the concept of ‘independence’ was debated and shifted in meaning, allowing the term to be operationalised to different ends. It gives particular attention to the birth of Channel 4 in 1982 and the subsequent rapid growth of an independent ‘sector’. Throughout, the thesis explores the tensions between the political, economic and social aims of independent television production and how these impact on the role of the producer. The thesis employs an empirical methodology to investigate the independent television producer’s role. It uses qualitative data, principally original interviews with both employers and employees in the four companies, to provide a nuanced and detailed analysis of the complexities of the producer’s role. Rather than independence, the thesis uses network analysis to argue that a television producer’s role is characterised by sets of negotiated dependencies, through which professional agency is exercised and professional identity constructed and performed. -

Joseph Gilgun

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Joseph Gilgun Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company BRASSIC Vinnie Daniel O'Hara Sky PREACHER Series 1-4 Cassidy Various Sony TV/AMC Studios THIS IS ENGLAND '90 Woody Shane Meadows Warp Films/Channel 4 COMING UP - 'HENRY' Martin Michael Pearce Channel 4 RIPPER STREET Carmichael Various BBC MISFITS Series 3, 4 & 5 Rudy Wade Various Quite Funny Films/E4 THIS IS ENGLAND (Christmas Special) Woody Shane Meadows Warp Films/Channel 4 THIS IS ENGLAND '88 Woody Shane Meadows Warp Films/Channel 4 THIS IS ENGLAND '86 Woody Shane Meadows Warp Films/Channel 4 EMMERDALE Eli Dingle Various Yorkshire Television SORTED Car Mechanic Iain B. MacDonald BBC BIG DIPPERS Karl Kay Patrick Red Productions HOLLYOAKS Marcus Various Mersey Television SHAMELESS Series 2 Rico Various Channel 4 CORONATION STREET Jamie Armstrong Various Granada Film Title Role Director Production Company THE INFILTRATOR Dominic Brad Furman Good Films THE LAST WITCH HUNTER Ellic Breck Eisner Summit Entertainment PRIDE Mike Matthew Warchus Proud Films James Mather/Stephen St. LOCK OUT Hydell Europa Corp. Leger SCREWED Gleeson Reg Traviss Screwed Films HARRY BROWN Kenny Daniel Barber Marv Films THIS IS ENGLAND Woody Shane Meadows Warp Films Theatre Title Role Theatre/Producer HANKY PARK Nobby Lowry Theatre Edinburgh Fringe 2002/Unity BORSTAL BOY Charlie Theatre, Liverpool/Capitol -

In Film Mike Gubbins

TAKE 12 DIGITAL INNOVATION IN FILM MIKE GUBBINS 3 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 A TAKE 12 INTRODUCTION 5 CHAPTER 2 THE TAKE 12 APPROACH 7 CHAPTER 3 CONTEXT 11 CHAPTER 4 CASE STUDIES 21 B3 23 BREAKTHRU FILMS 25 FILM EXPORT UK (FEUK) 27 HOLLYWOOD CLASSICS 29 LUX 31 METRODOME 33 MOSAIC FILMS 35 ONEDOTZERO 37 REVOLVER ENTERTAINMENT 39 VOD ALMIGHTY 41 WARP FILMS 43 ZINI 45 CHAPTER 5 INNOVATION READY 47 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSIONS 55 Toolbox items are links to other resources and documents, referenced in boxes on many pages. These are links to richer content, more details, or useful documents produced during Take 12 that could be re-used for anyone seeking to apply lessons in their business. 4 5 CHAPTER 1 A TAKE 12 INTRODUCTION Take 12 Digital Innovation In Film was an normally be beyond the financial reach of most individual initiative that responded to two dawning SMEs. realities at the time of its launch in the And through working on a range of business plans Spring of 2008. and ideas, the programme would be able to create a framework for the ‘innovation ready’ business. The first was that digital change and the audience demand it had enabled would have profound and This process of evaluating plans, testing ideas irreversible consequences for the whole UK film industry against market realities and customer research, and (see Chapter 2). implementing specific projects was carried out in ‘live’ conditions, running alongside day-to-day work. The second was that the responsibility for dealing with these challenges – and for grasping the opportunities And the results were to be shared with the whole industry. -

Rightsholder-List.Pdf

IE-Ireland COR - Corporations: Employees Facilities Label 101 Films 12 Yard Productions 123 Go Films 1A Productions Limited 1st Miracle Productions Inc 20th Century Studios (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) 2929 Entertainment 365 Flix International 3DD Entertainment 41 Entertaiment LLC 495 Productions 4Licensing Corporation (fka 4Kids Entertainment) 7&7 Producers Sales Services 9 Story Enterprises 99Pro Media Gmbh A Really Happy Film (HK) Ltd. (fka Distribution Workshop A&E Networks Productions Aardman Abacus Media Rights Ltd Abbey Home Media Abduction Films Abot Hameiri About Premium Content SAS Abso Lutely Productions Absurda Acacia ACIP (fka Angel City Factory (ACP)) Acorn Media Acorn Media Acorn TV Actaeon Films Action Concept Film und Stuntproduktion (ex. Germany) Active Entertainment Adhoc Films Adler Media Adult Swim Productions Adventure Line Productions (ALP) Adventure Pictures Aenon Affiliate of Valiant Women Society (fka Maralee Dawn Ministries) After Dark Films Agatha Christie Productions Ager Film AI Film AIM Group (dba Cinevision Global -Ambassador Film Library) Air Productions Akkord Film Produktion Aktis Films International Al Dakheel Inc Alberio Films Alchemy Alchemy Television Group Alcina Pictures (ex. Canada) Alcon Entertainment Alcon Television All3media International Alley Cat Films Alliance Atlantis International Distribution Alliance Atlantis International Distribution Allied Vision Ltd All-In-Production Gmbh Allmedia Pictures Gmbh Alonso Entertainment Gmbh Aloupis Productions Altitude Films Sales Amazing -

Made in Britain: Warp Films at 10

13/14 Made in Britain: Warp Films at 10 A 10th Anniversary celebration at BFI Southbank In spring last year BFI Southbank launched Made in Britain, an annual exploration of contemporary British Cinema. In April the strand returns with a selection of the most ground- breaking titles from Warp Films, as we celebrate this seminal production companyǯ ͳͲ anniversary. Warp Films have in their way defined a decade and are helping to shape the future of British cinema, offering the opportunity for highly original and exciting talent to make films that might otherwise be overlooked. BAFTA-winning films such as the This is England (2006), Four Lions (2010) and Tyrannosaur (2011) will all feature, but the season will launch with what promises to be a truly awesome event when ǯ (2004), directed by Shane Meadows, will screen with a live music accompaniment Ȃ featuring musicians from UNKLE and Clayhill plus Jah Wobble - at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on Friday 29 March. There will also be a Warp Films Shorts Programme, including work by Lynne Ramsay, Chris Cunningham and Paddy Considine plus a BUG: Warp Records Special, followed by an aftershow in benugo with Warp DJs hitting the decks. To complement this amazing showcase there will be an exhibition of newly designed Warp Film posters, by Sheffield-based artist Pete McKee, displayed exclusively in The Atrium at BFI Southbank. Warp Films have been at the heart of a new wave of filmmaking in the UK and have provided a platform for fresh, radical ideas and emerging talent from film and TV. -

Films: Rosa Romero Commercials, Low Budget Features & Documentaries: Lucie Llewellyn

PORTFOLIO Andrea Flesch Profession: Costume designer / Stylist Foreign languages spoken: english / french Location: Budapest / Hungary Email: andreafl[email protected] Web: www.andreaflesch.com Agent: Casarotto Ramsey & Associates Limited Web: www.casarotto.co.uk Short Films, Television Series, Comedy, Pilots: Amy Davies Television Drama: Emma Trounson, Kate Bloxham Feature Films: Rosa Romero Commercials, Low Budget Features & Documentaries: Lucie Llewellyn Films: Colette Producer: Elizabeth Karlsen, Pamela Koffler Production company: Number 9 Films, Killer Films / Pioneer Pictures Director: Wash Westmoreland DOP: Giles Nuttgens Starring: Keira Knightley, Dominic West, Denise Gough, Fiona Shaw, Aysha Hart 2017 X Company Season 3 - TV series Producer: Mark Ellis, Stephanie Morgenstern Production company: CBC / Pioneer Pictures Director: Grant Harvey, Paolo Barzman, Julian Gilbey, Amanda Tapping, Stephanie Morgenstern DOP: Stephan Pehrsson Starring: Jack Laskey, Evelyne Brochu, Warren Brown, Torben Liebrecht 2016 Budapest Noir Producer: Ildiko Kemeny Production company: Pioneer Pictures Director: Eva Gardos DOP: Elemer Ragalyi Starring: Krisztian Kolovratnik, Reka Tenki, Zsolt Anger, Kata Dobo, Adel Kovats, Janos Kulka 2016 Kills On Wheels Producer: Judit Stalter Production company: Laokoon Filmgroup Director: Attila Till DOP: Imre Juhász Starring: Szabolcs Thuroczy, Zoltan Fenyvesi, Adam Fekete, Monika Balsai, Dusan Vitanovic 2015 X Company Season 2 - TV series Nominated for Best Costume Design Producer: Mark Ellis, Stephanie Morgenstern 2017 -

Oppdatert Liste Samarbeidspartnere

OPPDATERT LISTE Banijay International Ltd Carey Films Ltd SAMARBEIDSPARTNERE Bankside Films Cargo Film & Releasing Bard Entertainment Carnaby Sales and Distribution Ltd Bardel Distribution Carrere Group D.A. 12 Yard Productions BBC Worldwide Cartoon Network 2929 Entertainment LLC BBL Distribution Inc. Cartoon One 3DD Entertainment BBP Music Publishing c/o Black Bear Caryn Mandabach Productions 9 Story Enterprises Pictures Casanova Multimedia A&E Channel Home Video Beacon Communications Cascade Films Pty Ltd Abduction Films Ltd Becker Group Ltd. Castle Hill Productions Acacia Beijing Asian Union Culture and Media Cats and Docs SAS ACC Action Concept Cinema GmbH & Investment CCI Releasing Co. KG Bejuba Entertainment CDR Communications ACI Bell Phillip Television Productions Inc. Celador Productions Acorn Group Benaroya Pictures Celestial Filmed Entertainment Ltd. ACORN GROUP INC Bend it Like Beckham Productions Celluloid Dreams Acorn Media Bentley Productions Celsius Entertainment Actaeon Films Berlin Animation Film Gmbh Celsius Film Sales Action Concept Best Film and Video Central Independent Television Action Concept Film und Best Picture Show Central Park Media Stuntproduktion GmbH Betty TV Channel 4 Learning Action Image GmbH & Co. KG Beyond International Ltd Chapter 2 Adness Entertainment Co. Ltd. Big Bright House of Tunes Chatsworth Enterprises Adult Swim Productions Big Idea Entertainment Children's Film And Television After Dark Films Big Light Productions Foundation Ager Film Big Talk Productions Chorion Plc AIM Group LLC. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association / Christian Television Association Akkord Film Produktion GmBH World Wide Pictures Ciby 2000 Alain Siritzky Productions Bio Channel Cineflix International Media Alameda Films BKN International Ltd. Cinema Seven Productions Albachiara S.r.l. Blakeway Productions Cinematheque Collection Alcine Pictures Ltd.