Vol. 20 No 1 April 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

Der Frühling Ist Da! © 123Rf, Alexander Raths © 123Rf

50 > Unsere Generation WIRApril 2018 Hausruckviertel l Der Frühling ist da! © 123rf, Alexander Raths © 123rf, Pensionistenverband Oberösterreich Themen der Zeit – wir reden mit! FPÖ-Attacken auf den ORF Nach FPÖ-Attacken auf den ORF fordern deutsche Starjournalisten Bundeskanzler Kurz zum Eingreifen auf. Mag. Werner Guttmann, ehem. SP-Vizebürgermeister Großraming und kfm. Direktor der Ennskraftwerke AG. Beinahe jede/r von uns hört und schaut vermutlich täglich Sendungen im ORF. Unser öffentlich rechtlicher Rundfunk Aktuell hat, anders als Privatsender, den Auftrag, neben Unterhaltung auch ein umfassen- des Informations- und Kulturangebot zu bieten. Der ORF hat täglich mehr als 20 Nachrichtensendungen, Dokumentatio- nen, große Kultursendungen, Auslands- korrespondenten von Washington bis Peking, neun Landesstudios, Randsport- © ORF/Thomas Ramstorfer arten, Kinderprogramm usw. Für dieses umfassende öffentlich-recht- Sie alle sind, wie auch in österreichi- liche Angebot von weit über 50 Stunden schen Zeitungen zu lesen war, „bestürzt Schweizer gegen Abschaffung täglich bezahlen wir 80 Cent am Tag, rund darüber, dass Strache Armin Wolf und der Rundfunkgebühren 25 Euro im Monat. Das ist weniger, als ein hunderte Journalistinnen und Journalisten Fast 72 Prozent der Schweizerin- Abonnement mancher Tageszeitung. des ORF als Propagandisten und Produ- nen und Schweizer sagten kürzlich Nicht alle von uns werden mit dem zenten von Falschmeldungen verleumde“. „Nein“ zur Abschaffung der Gebüh- Programm immer zufrieden sein, aber die „Den Versuch des Vizekanzlers der öster- ren fürs Schweizer Fernsehen. Auch massiven Angriffe der FPÖ gefährden die reichischen Regierung, den persönlichen in Österreich gibt es bereits eine Pressefreiheit und es geht offenbar darum, Ruf von Journalisten zu beschädigen und Petition für die Unabhängigkeit des den ORF völlig unter politische Kontrolle zu deren Glaubwürdigkeit zu untergraben, ORF – hier kann man unterzeichnen: bringen. -

NICOLA BENEDETTI ELGAR VIOLIN CONCERTO London Philharmonic Orchestra Vladimir Jurowski EDWARD ELGAR 1857–1934

NICOLA BENEDETTI ELGAR VIOLIN CONCERTO London Philharmonic Orchestra Vladimir Jurowski EDWARD ELGAR 1857–1934 Violin Concerto in B minor Op.61 1 I Allegro 17.28 2 I Andante 11.36 3 III Allegro molto 18.42 4 Sospiri Op.70 4.10 5 Salut d’amour Op.12 3.09 6 Chanson de nuit Op.15 No.1 3.41 NICOLA BENEDETTI violin London Philharmonic Orchestra Vladimir Jurowski Petr Limonov piano (4–6) 3 ELGAR'S VIOLIN MUSIC Out of all the instruments Edward Elgar of moving between notes, the use of played, the violin was his speciality. vibrato as a constant tonal element, and Trombone and bassoon filled in useful so on – were developed by a number of gaps, while his improvisatory piano playing young players, but are chiefly identified (which he said “would madden with envy with the Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler, all existing pianists”) served to summon the dedicatee of Elgar’s concerto. Elgar up the harmonies of his inner orchestra; met Kreisler in Leeds in 1904, and again but it was the violin that gave him the in Norwich the next year, and very soon invaluable stimulus of playing in the Three began to sketch the concerto. It had Choirs Festival (under no less a master to take a back seat while he wrote than Dvořák on one occasion); the violin The Kingdom (1906) and the mighty First that he studied with a top London teacher; Symphony (1908), but in January 1910, the violin which dominates his earliest Elgar played through the concerto’s slow opus numbers, with Op.15 bringing the movement with a friend, Lady Speyer, a running total to 18 separate pieces. -

Bundesgesetzblatt Für Die Republik Österreich

1 von 5 BUNDESGESETZBLATT FÜR DIE REPUBLIK ÖSTERREICH Jahrgang 2006 Ausgegeben am 3. April 2006 Teil II 139. Verordnung: 10. Änderung der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestverordnung 2006 139. Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Gesundheit und Frauen zur 10. Änderung der Verordnung über Schutzmaßnahmen wegen Verdachtsfällen von Geflügelpest bei Wildvögeln (10. Änderung der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestverordnung 2006) Gemäß § 1 Abs. 5 und 6 sowie der §§ 2 und 2c des Tierseuchengesetzes RGBl. Nr. 177/1909, zuletzt geändert durch das Bundesgesetz BGBl. I Nr. 67/2005, wird verordnet: § 1. Die Anhänge der Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Gesundheit und Frauen über Schutzmaßnahmen wegen Verdachtsfällen von Geflügelpest bei Wildvögeln (Wildvogel- Geflügelpestverordnung 2006), BGBl. II Nr. 80/2006, zuletzt geändert durch die Verordnung BGBl. II Nr. 132/2006, werden durch die Anhänge zu dieser Verordnung ersetzt. § 2. Diese Verordnung tritt mit Ablauf des 31. März 2006 in Kraft. Rauch-Kallat Anhang A Schutzzonen Die Schutzzone 1 ist ab 11. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 2 ist ab 9. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 3 ist ab 11. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 4 ist ab 17. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 5 ist ab 25. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 6 ist ab 25. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 7 ist ab 25. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 8 ist ab 25. März 2006 aufgehoben. Die Schutzzone 9 umfasst ab 10. März 2006: In Oberösterreich: alle Gebiete der Katastralgemeinden Fraunhof und Gattern der Gemeinde Schardenberg, die innerhalb eines 3 km Radius gemessen vom linken Innufer der Staumauer des Kraftwerkes Ingling bei Passau, liegen. www.ris.bka.gv.at BGBl. II - Ausgegeben am 3. -

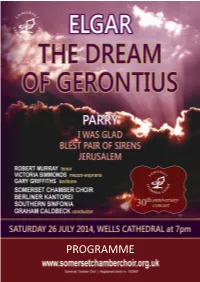

To View the Concert Programme

PROGRAMME Happy birthday Somerset Chamber Choir! Welcome to our 30th birthday party! We are delighted that our very special invited guests, our loyal choir ‘Friends’ and everyone here tonight could join us for this occasion. As if that weren’t enough of a nucleus for a wonderful party, the BERLINER KANTOREI have travelled from Berlin to celebrate with us too ... their ‘return match’ for an excellent time some of us enjoyed singing with them when they hosted us last autumn. This concert comes at the end of a week which their party of singers and supporters have spent staying in and sampling the delights of Somerset; we hope their experience has been a memorable one and we wish them bon voyage for their journey home. Ten years of singing together in the 1970s and 1980s under the inspirational direction of the late W. Robert Tullett, founder conductor of the Somerset Youth Choir, welded a disparate group of young people drawn from schools across Somerset, into a close-knit group of friends who had discovered the huge pleasure of making music together and who developed a passion for choral music that they wanted to share. The Somerset Chamber Choir was founded in 1984 when several members who had become too old to be classed as “youths” left the Youth Choir and, with the approval of Somerset County Council, drew together other like-minded singers from around the County. Blessed with a variety of complementary skills, a small steering group set about developing a balanced choir and appointed a conductor, accompanist and management team. -

Christoph Eschenbach Dirigiert Mahler 6

Eschenbach dirigiert Mahler 6 Samstag, 08.04.17 — 19.30 Uhr Lübeck, Musik- und Kongresshalle GUSTAV MAHLER Sinfonie Nr. 6 a-Moll ChristopH ESchenbAcH Dirigent „Glück flammt hoch am Rande des Grauens“ Am 20. Mai 1906 machte sich Gustav Mahler auf die Meine VI. wird Reise nach Essen, um die Uraufführung seiner Sechs Rätsel aufgeben, ten Sinfonie vorzubereiten – mit gemischten Gefüh len. Denn zum einen zweifelte er an der Leistungs an die sich nur fähigkeit des Essener Orchesters, das qualitativ dem eine Generation Kölner GürzenichOrchester, mit dem er zwei Jahre zuvor seine Fünfte erarbeitet hatte, klar unterlegen heranwagen darf, NDR ELbpHilharmoNiE war. Zum anderen hatte man aufgrund der großen die meine ersten Orchester Besetzung das Orchester der Stadt Utrecht zur Verstär kung holen müssen, über dessen Güte sich Mahler fünf in sich auf- zuvor bei seinem Freund Willem Mengelberg zwar genommen hat. ausführlich erkundigt hatte und beruhigt worden war. Doch würden sich beide Orchester problemlos zu Gustav Mahler im Jahr 1904 einem Klangkörper zusammenfügen lassen? Mahlers Bedenken sollten sich als unbegründet erweisen. „Sehr zufrieden von der 1. Probe!“, heißt es Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) in einem Brief an Alma Mahler vom 2. Mai 1906. Sinfonie Nr. 6 aMoll „Orchester hält sich famos und klingen thut Alles, Entstehung: 1903 – 04 | Uraufführung: Essen, 27. Mai 1906 | Dauer: ca. 85 Min. wie ich es wünschen kann.“ Dennoch wurde die Pre I. Allegro energico, ma non troppo. miere am 27. Mai 1906 im Essener Saalbau nur ein Heftig, aber markig Achtungserfolg, bei dem laut den Erinnerungen des II. Scherzo. Wuchtig – Trio. Altväterisch, grazioso damals anwesenden Dirigenten Klaus Pringsheim III. -

Programme Scores 180627Da

Symposium Richard Wagner and his successors in the Austro-German conducting tradition Friday/Saturday, 2/3 November 2018 Bern University of the Arts, Papiermühlestr. 13a/d A symposium of the Research Area Interpretation – Bern University of the Arts, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music, London www.hkb-interpretation.ch/annotated-scores Richard Wagner published the first major treatise on conducting and interpretation in 1869. His ideas on how to interpret the core Classical and early Romantic orchestral repertoire were declared the benchmark by subsequent generations of conductors, making him the originator of a conducting tradition by which those who came after him defined their art – starting with Wagner’s student Hans von Bülow and progressing from him to Arthur Nikisch, Felix Weingartner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Wilhelm Furtwängler and beyond. This conference will bring together leading experts in the research field in question. A workshop and concert with an orchestra with students of the Bern University of the Arts, the Hochschule Luzern – Music and the Royal Academy of Music London, directed by Prof. Ray Holden from the project partner, the Royal Academy of Music, will offer a practical perspective on the interpretation history of the Classical repertoire. A symposium of the Research Area Interpretation – Bern University of the Arts, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music, London Head Research Area Interpretation: Martin Skamletz Responsible for the conference: Chris Walton Scientific collaborator: Daniel Allenbach Administration: Sabine Jud www.hkb.bfh.ch/interpretation www.hkb-interpretation.ch Funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation SNSF Media partner Symposium Richard Wagner and his successors Friday, 2 November 2018 HKB, Kammermusiksaal, Papiermühlestr. -

An Afternoon at the Proms 24 March 2018

AN AFTERNOON AT THE PROMS 24 MARCH 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM MELBOURNE SIR ANDREW DAVIS TASMIN SYMPHONY LITTLE ORCHESTRA Courtesy B Ealovega Established in 1906, the Chief Conductor of the Tasmin Little has performed Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Melbourne Symphony Melbourne Symphony in prestigious venues Sir Andrew Davis conductor Orchestra (MSO) is an Orchestra, Sir Andrew such as Carnegie Hall, the arts leader and Australia’s Davis is also Music Director Concertgebouw, Barbican Tasmin Little violin longest-running professional and Principal Conductor of Centre and Suntory Hall. orchestra. Chief Conductor the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Her career encompasses Sir Andrew Davis has been He is Conductor Laureate performances, masterclasses, Elgar In London Town at the helm of MSO since of both the BBC Symphony workshops and community 2013. Engaging more than Orchestra and the Toronto outreach work. Vaughan Williams The Lark Ascending 3 million people each year, Symphony, where he has Already this year she has the MSO reaches a variety also been named interim Vaughan Williams English Folksong Suite appeared as soloist and of audiences through live Artistic Director until 2020. in recital around the UK. performances, recordings, Britten Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra In a career spanning more Recordings include Elgar’s TV and radio broadcasts than 40 years he has Violin Concerto with Sir Wood Fantasia on British Sea Songs and live streaming. conducted virtually all the Andrew Davis and the Royal Elgar Pomp and Circumstance March No.1 Sir Andrew Davis gave his world’s major orchestras National Scottish Orchestra inaugural concerts as the and opera companies, and (Critic’s Choice Award in MSO’s Chief Conductor in at the major festivals. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Kalendár Výročí

Č KALENDÁR VÝROČÍ 2010 H U D B A Zostavila Mgr. Dana Drličková Bratislava 2009 Pouţité skratky: n. = narodil sa u. = umrel výr.n. = výročie narodenia výr.ú. = výročie úmrtia 3 Ú v o d 6.9.2007 oznámili svetové agentúry, ţe zomrel Luciano Pavarotti. A hudobný svet stŕpol… Muţ, ktorý sa narodil ako syn pekára a zomrel ako hudobná superstar. Muţ, ktorého svetová popularita nepramenila len z jeho výnimočného tenoru, za ktorý si vyslúţil označenie „kráľ vysokého cé“. Jeho zásluhou sa opera ako okrajový ţáner predrala do povedomia miliónov poslucháčov. Exkluzívny svet klasickej hudby priblíţil širokému publiku vystúpeniami v športových halách, účinkovaním s osobnosťami popmusik, či rocku a charitatívnymi koncertami. Spieval takmer výhradne taliansky repertoár, debutoval roku 1961 v úlohe Rudolfa v Pucciniho Bohéme na scéne Teatro Municipal v Reggio Emilia. Jeho ľudská tvár otvárala srdcia poslucháčov: bol milovníkom dobrého jedla, futbalu, koní, pekného oblečenia a tieţ obstojný maliar. Bol poverčivý – musel mať na vystú- peniach vţdy bielu vreckovku v ruke a zahnutý klinec vo vrecku. V nastupujúcom roku by sa bol doţil 75. narodenín. Luciano Pavarotti patrí medzi najväčších tenoristov všetkých čias a je jednou z mnohých osobností, ktorých výročia si budeme v roku 2010 pripomínať. Nedá sa v úvode venovať detailnejšie ţiadnemu z nich, to ani nie je cieľom tejto publikácie. Ţivoty mnohých pripomínajú román, ľudské vlastnosti snúbiace sa s géniom talentu, nie vţdy v ideálnom pomere. Ale to je uţ úlohou muzikológov, či licenciou spisovateľov, spracovať osudy osobností hudby aj z tých, zdanlivo odvrátených stránok pohľadu ... V predkladanom Kalendári výročí uţ tradične upozorňujeme na výročia narodenia či úmrtia hudobných osobností : hudobných skladateľov, dirigentov, interprétov, teoretikov, pedagógov, muzikológov, nástrojárov, folkloristov a ďalších. -

Holst, the Toronto Symphony, Andrew Davis

Holst The Planets mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: The Planets Country: Canada Released: 1986 Style: Modern MP3 version RAR size: 1165 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1455 mb WMA version RAR size: 1248 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 915 Other Formats: ADX WAV MP4 TTA MIDI DXD AA Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Mars, The Bringer Of War 7:50 A2 Venus, The Bringer Of Peace 7:12 A3 Mercury, The Winged Messenger 4:04 A4 Jupiter, The Bringer Of Jollity 7:24 B1 Saturn, The Bringer Of Old Age 8:30 B2 Uranus, The Magician 5:45 Neptune, The Mystic B3 8:05 Chorus – Toronto Children's ChorusChorus Master – Jean Ashworth Bartle Companies, etc. Recorded At – Centre In The Square, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada Credits Composed By – Gustav Holst Conductor – Andrew Davis Engineer [Assistant] – Malcolm Harris Engineer, Producer – Anton Kwiatkowski Liner Notes – Frank Granville Barker, Godfrey Ridout Orchestra – The Toronto Symphony* Notes Recorded in The Centre in The Square, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada on january 20, 1986. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Holst*, The Holst*, The Toronto CDC Toronto Symphony*, Andrew Angel CDC US 1986 547417 Symphony*, Davis - The Planets Records 547417 Andrew Davis (CD, Album) Holst*, The Holst*, The Toronto Toronto Symphony*, Andrew Angel DS 537362 DS 537362 US 1986 Symphony*, Davis - The Planets Records Andrew Davis (LP, Album, Club) His Holst*, The Holst*, The Toronto Master's EL 27 0429 Toronto Symphony*, Andrew Voice, His EL 27 0429 UK 1986 1 Symphony*, Davis - The Planets Master's 1 Andrew Davis (LP) Voice Digital Holst*, The Holst*, The Toronto CDC Toronto Symphony*, Andrew Angel CDC US 1986 547417 Symphony*, Davis - The Planets Records 547417 Andrew Davis (CD, Album, Club) Holst*, The Holst*, The Toronto 4DS Toronto Symphony*, Andrew Angel 4DS US Unknown 537362 Symphony*, Davis - The Planets Records 537362 Andrew Davis (Cass, Club) Related Music albums to The Planets by Holst Gustav Holst, The London Symphony Orchestra, Gustav Holst - The Planets Op. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008).