Islam and Modernity: the Case of Turkey and the Welfare Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Welfare Party in Perspective

Third World Quarterly ISSN: 0143-6597 (Print) 1360-2241 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctwq20 The political economy of Islamic resurgence in Turkey: The rise of the Welfare Party in perspective Ziya Onis To cite this article: Ziya Onis (1997) The political economy of Islamic resurgence in Turkey: The rise of the Welfare Party in perspective, Third World Quarterly, 18:4, 743-766, DOI: 10.1080/01436599714740 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436599714740 Published online: 25 Aug 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1047 View related articles Citing articles: 61 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ctwq20 Download by: [SOAS, University of London] Date: 06 March 2017, At: 22:18 ThirdW orldQu arterly,V ol18,No4,pp743±766,1997 ThepoliticaleconomyofIslamic resurgence inTurkey:therise ofthe WelfareParty in perspective ZIÇ YA OÈ NISË Therisingelectoralfortu neso ftheWelfareP arty(Refah P artisi( RP)), a party thatd ifferentiatesitselfsh arplyfro mthe`orthodox’p artieso ftherightorlefto f thepoliticalspectrumbycam paigningex plicitlyonanIslam istp latform, constitutesth emosto bviousorv isiblesig nofIslamicresurg encein th eTurkish 1 context. Theturning-pointinth eevolutionof RP intoa majorpoliticalmove- mentcamewiththe m unicipalg overnmentelecti onsofMarch1 994during whichth epartym anagedto cap tureth emayorshipsofthetwokeym etropolitan areaso fIstanbulandA nkara.T hisvicto -

Redalyc.Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: a Case Study On

Argumentum E-ISSN: 2176-9575 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Brasil Sinem ARIKAN, Elif Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: A Case Study on Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Argumentum, vol. 8, núm. 1, enero-abril, 2016, pp. 115-125 Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Vitória, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=475555256018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18315/argumentum.v8i1.11884 ARTIGO Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: A Case Study on Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Prestação de assistência social a nível local: um estudo de caso no Município de Istambul Elif Sinem ARIKAN1 Abstract: In this article I tried to find traces of a neo-conservative model the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipal- ity in Turkey. Firstly I tried to explain significant collaboration between liberalism and conservatism in the neoliberal context. Subsequently, I tried to evaluate the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality to see the neo- conservative administration’s effects on local administrations based on market-oriented administration ra- tionale. I tried to explain that the gender discourse was strengthened because of such administration rationale. I tried to evaluate this matter profoundly. I mentioned the Ladies Commission of RP (Welfare Party) and Kadın Koordinasyon Merkezi (Women Coordination Center (WCC)) in the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality as examples of models of conservative women’s political organizations. Keywords: Neoliberalism. -

Dynamics of Youth Euroscepticism a Thesis

DYNAMICS OF YOUTH EUROSCEPTICISM A THESIS SUBMITED TO THE GARADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ÖNDER KÜÇÜKURAL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN SOCIOLOGY DECEMBER 2005 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof.Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sibel Kalaycıoğlu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Dr. Mustafa Şen Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Galip Yalman (METU, ADM) Dr. Mustafa Şen (METU, Sociology) Assist. Prof. Dr Aykan Erdemir (METU, Sociology) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Önder Küçükural Signature : iii ABSTRACT Dynamics of Youth Euroscepticism Küçükural, Önder M.Sc., Department of Sociology Supervisor: Dr. Mustafa Şen December 2005, 138 pages The aim of this thesis is to describe the dominant features of Euroscepticism in Turkish context and to understand its main dynamics with special reference to a particular group, the youth in Turkey. A field research was conducted in order to understand youth’s EU support. -

Voter Preferences, Electoral Cleavages and Support for Islamic Parties

Voter Preferences, Electoral Cleavages and Support for Islamic Parties Sabri Ciftci Department of Political Science Kansas State University, Manhattan [email protected] Yusuf Tekin Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, TURKEY [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2009 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 2‐5 2009, Chicago, IL Abstract Increasing scholarly attention has recently been focused upon the origins and fortunes of Islamic parties. This paper examines the individual determinants of support for these parties utilizing the fifth wave of the World Values Survey. It is argued that the distribution of individual preferences along political cleavages like left‐right, secularism‐Islamism, and regime‐opposition are critical explanatory variables. The cases under investigation are Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey and Party of Justice and Development (PJD) in Morocco. The results of the multinomial logit show that Islamic parties obtain support from a broad spectrum of voters and this support base is best understood in relation to the distribution of voter preferences for rival parties. Furthermore, left‐right and Islamism appear to be the most important cleavages in the electoral markets under investigation. 1 Introduction Increasing scholarly attention has recently been focused upon the origins and fortunes of Islamic parties. In this vein, a good amount of research examined the Islamic party moderation (Kalyvas, 2000; Schwedler, 2007) and their commitment to democracy (Tibbi, 2008, p. 43-48; Nasr, 2005). While there is merit in investigating these questions, it is also important to understand the microlevel foundations of support for Islamic parties. Surprisingly, little empirical research has been conducted toward this end (for an exception see Carkoglu, 2006; Tepe, 2007) and studies with a comparative orientation are rare (Garcia-Rivero and Kotze, 2007; Tepe and Baum, 2008). -

TRANSFORMATION of POLITICAL ISLAM in TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’S Pro-EU Turn

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.4 pp. 463–483 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com TRANSFORMATION OF POLITICAL ISLAM IN TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’s Pro-EU Turn Saban Taniyici ABSTRACT The recent changes in the Islamist party’s ideology and policies in Turkey are analysed in this article. The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) was ousted from power in June 1997 and was outlawed by the Consti- tutional Court (CC) in March 1998. After the ban, the WP elite founded the Virtue Party and changed policies on a number of issues. They emphasized democracy and basic human rights and freedoms in the face of this external shock. The WP’s hostile policy toward the European Union (EU) was changed. This process of change is discussed and it is argued that the EU norms presented a political opportunity structure for the party elites to influence the change of direction of the party. When the VP was banned by the CC in June 2001, the VP elites split and founded two parties which differ on a number of issues but have positive policies toward the EU. KEY WORDS European Union party change political Islam political oppor- tunity structure Turkey Introduction The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) in Turkey recently changed its decades-old policy of hostility toward the European Union (EU) and began strongly to support Turkey’s accession to the Union, thereby raising doubts about the inevitability of a civilizational conflict between Islam and the West. 1 This change was part of the party’s broader image transformation which took place after its leader, Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan,2 was forced by the Turkish political establishment to resign from a coalition government in June 1997. -

London Wide Assembly Final Results

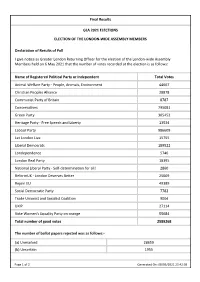

Final Results GLA 2021 ELECTIONS ELECTION OF THE LONDON-WIDE ASSEMBLY MEMBERS Declaration of Results of Poll I give notice as Greater London Returning Officer for the election of the London-wide Assembly Members held on 6 May 2021 that the number of votes recorded at the election is as follows: Name of Registered Political Party or Independent Total Votes Animal Welfare Party - People, Animals, Environment 44667 Christian Peoples Alliance 28878 Communist Party of Britain 8787 Conservatives 795081 Green Party 305452 Heritage Party - Free Speech and Liberty 13534 Labour Party 986609 Let London Live 15755 Liberal Democrats 189522 Londependence 5746 London Real Party 18395 National Liberal Party - Self-determination for all! 2860 ReformUK - London Deserves Better 25009 Rejoin EU 49389 Social Democratic Party 7782 Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition 9004 UKIP 27114 Vote Women's Equality Party on orange 55684 Total number of good votes 2589268 The number of ballot papers rejected was as follows:- (a) Unmarked 28659 (b) Uncertain 1955 Page 1 of 2 Generated On: 08/05/2021 23:42:39 (c) Voting for too many 24212 (d) Writing identifying voter 88 (e) Want of official mark 17 Total 54931 And I do hereby declare the eleven London-wide Assembly Member seats have been allocated and filled as follows Name of Registered Political Party Seat Number or Independent 1 Green Party BERRY Sian 2 Liberal Democrats PIDGEON Caroline Valerie 3 Green Party RUSSELL Caroline 4 Conservatives BAILEY Shaun 5 Conservatives BOFF Andrew 6 Green Party POLANSKI Zack 7 Conservatives -

Full Text (PDF)

PEARSON JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES 2020 Doi Number :http://dx.doi.org/10.46872/pj.83 THE ROLE OF N. ERBAKAN AND THE WELFARE PARTY IN THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF TURKEY Dr. Namig Mammadov Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences ORCID: 0000-0003-4356-6111 Özet Bu makale, Necmettin Erbakan'ın ve Refah Partisi'nin modern Türkiye'nin siyasi tarihindeki rolünü incelemekte ve analiz etmektedir. Türkiye'de Milli Görüş Hareketi'nin oluşumunda ve gelişiminde ideoloji, sosyal taban ve ana itici güçler ile faaliyetleri de bu makalenin incelenme kısmıdır. Makale ayrıca hareketin önderi, önde gelen bilim adamı ve araştırmacısı, profesör Necmeddin Erbakan'ın rolü de dahil olmak üzere hareketin oluşumunu ve gelişimini etkileyen tarihsel koşulların yanı sıra siyasi arenaya girme nedenleri ve sonuçları da analiz ediyor. N. Erbakan'ın Türkiye'nin siyasi hayatındaki rolü araştırılarak değerlendirilmeye çalışılmıştır. Refah Partisi'nin ana ideolojisinin faizsiz bir serbest piyasa ekonomisi, üretimin güçlendirilmesi, temel insan haklarının korunduğu adil bir toplumun kurulması vb. olduğu kaydedilmiştir. Refah Partisi (RP), aynı yönü temsil eden Ahmet Tekdal liderliğinde 1983 yılında kuruldu. Siyasi yasakların kaldırılmasının ardından N. Erbakan yeniden parti başkanlığına seçildi. 1990'lar, Milli Görüş hareketinin gelişiminde yeni bir aşamaya geldi ve Refah Partisi'nin itibarı yükselmeye başladı. 1995 seçimlerinde parti oyların yüzde 21'ini kazandı. 1996 yılında N. Erbakan, Tansu Çiller liderliğindeki Doğru Yol Partisi ile koalisyon hükümeti kurdu. Bu hükümet 28 Şubat süreci sonucunda istifa etti ve parti feshedildi. Parti üyeleri Fazilet Partisi'ni kurdu. Anahtar kelimeler: Türkiye, N. Erbakan, Milli Görüş Hareketi, Milli Nizam Partisi, Refah Partisi Abstract This article examines and analyzes the role of Najmeddin Erbakan and the Welfare Party in the political history of modern Turkey. -

From Ruler to Pariah: the Life and Times of the True Path Party

6 From Ruler to Pariah: The Life and Times of the True Path Party ÜMİT CİZRE The historical conditions surrounding the birth of the True Path Party (Doğru Yol Partisi—DYP) on June 23, 1983 are identical to the labor pains of its predecessor, the Justice Party (Adalet Partisi—AP), on November 20, 1961. The AP had established itself as the principal heir to the Democratic Party (Demokrat Parti—DP) which was closed down by the 1960 military coup. The military rulers rooted the emergence of both the AP and DYP in the closure of their predecessor parties. More importantly, this time the crisis coincided with the challenges and uncertainties posed by new global trends, a generalized political phenomenon of democratization, and free market economy being the most significant ones. This contribution will consider the life and times of the DYP essentially in terms of the language, method, and logic of its reluctant change over time.1 HISTORICAL LUGGAGE AND CONJUNCTURE For a political party, change is never simply a matter of summoning the political will necessary to put the correct formulas into practice. On the contrary, it is a process involving historical baggage, and characterized by conflict and bargaining. In general, transformation of parties is understood in the literature as being caused by electoral environment, a dramatic economic crisis, and such intra-party factors as leadership.2 In this case, however, change came in part due to the military coup and the subsequent closing and opening of political parties by the decisions of a junta. Neither the pre-1980 left nor right could readily embrace the ideas, values, assumptions of neo-liberalism, the dominant paradigm of the 1980s. -

Middle East Brief 22

The Changing Face of Turkish Politics: Turkey’s July 2007 Parliamentary Elections Dr. Banu Eligür On July 22, 2007, Turkey held early parliamentary elections, as a result of which the ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi—AKP) retained its majority. Because the AKP has roots in political Islam, most analyses of the election results so far have concentrated on the Islamist vs. secular debate—and, related to this, the question whether the AKP’s performance in government might make it a suitable model of governance for the Muslim world. Although the issue of secularism (along with increased PKK terrorism) dominated the political parties’ 2007 election campaigns, this Brief argues that the AKP’s tremendous success in the 2007 parliamentary elections cannot be explained by focusing exclusively on the Islamist vs. secular debate. The success of the AKP must also be attributed to the socioeconomic concerns of the Turkish public, particularly the poor segments of the population—and the AKP’s strong organizational party networks, which have enabled the party to satisfy poor voters’ socioeconomic demands. This Brief will demonstrate how the results of these parliamentary elections (shown in Table 1, below) have changed the face of Turkish politics in an unprecedented way. The AKP secured its victory despite the party’s mixed performance during its four-and-a-half-year rule. The party’s record was especially poor in dealing with the PKK (the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, also known as Kongra-Gel), and the threat and reality of terrorism; with the high unemployment rate and the increased crime rate; and with Turkey’s mounting foreign debt. -

Species of Political Parties: a New Typology

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.2 pp. 167–199 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi SPECIES OF POLITICAL PARTIES A New Typology Richard Gunther and Larry Diamond ABSTRACT While the literature already includes a large number of party typologies, they are increasingly incapable of capturing the great diversity of party types that have emerged worldwide in recent decades, largely because most typologies were based upon West European parties as they existed in the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries. Some new party types have been advanced, but in an ad hoc manner and on the basis of widely varying and often inconsistent criteria. This article is an effort to set many of the commonly used conceptions of parties into a coherent framework, and to delineate new party types whenever the existing models are incapable of capturing important aspects of contemporary parties. We classify each of 15 ‘species’ of party into its proper ‘genus’ on the basis of three criteria: (1) the nature of the party’s organization (thick/thin, elite-based or mass-based, etc.); (2) the programmatic orien- tation of the party (ideological, particularistic-clientele-oriented, etc.); and (3) tolerant and pluralistic (or democratic) versus proto-hegemonic (or anti-system). While this typology lacks parsimony, we believe that it captures more accurately the diversity of the parties as they exist in the contemporary democratic world, and is more conducive to hypothesis- testing and theory-building than others. KEY WORDS party organization party programmes party systems party types For nearly a century, political scientists have developed typologies and models of political parties in an effort to capture the essential features of the partisan organizations that were the objects of their analysis. -

Turkey: Information on the Islamic Welfare Party (IWP) And

Resource Information Center Turkey: Information on the Islamic Welfare Party (IWP) and... I Page 1 of 4 Turkey Response to TUR01001.SND Information Request Number: Date: 19 December 2000 Subject: Turkey: Information on the Islamic Welfare Party (IWP) and Islamic Virtue Party (IVP) and Protests Against the Headdress Ban From: INS Resource Information Center, Washington, DC Keywords: Turkey / Islam / Islamists / Islamic Fundamentalism / Islamic Welfare Party (IWP) / Refah Party (RP) / Islamic Virtue Party (IVP) / Fazilet Party (FP) / Headdress / Headscarf / Religious Clothing / Protest / Demonstration Query: 1) What are the Islamic Welfare Party and the Islamic Virtue Party? 2) What is the religious headdress movement and how has the Islamic Virtue Party been involved? 3) How are women who wear religious headdresses treated in Turkey? 4) In October 1998, were demonstrations in protest against the headdress ban held in Turkey, and how were those in attendance treated? Response: 1) What are the Islamic Welfare Party and the Islamic Virtue Party and how have they been involved in the religious headdress movement? The Islamic Virtue Party (VP, or Fazilet Party) is the most recent in a line of successive Islamist parties that trace their origin to the National Order Party (NOP) founded in 1970 by Necmettin Erbakan. VP was founded on December 17, 1997 as a successor to the Islamic Welfare Party (WP, or Refah Party), which was brought to court in mid-1997 and outlawed by the Constitutional Court in January 1998. The Court ruled that the Welfare Party had violated the principles of secularism and the law on political parties (MERIA Sept. -

The Institutional Decline of Parties in Turkey

10 THE INSTITUTIONAL DECLINE OF PARTIES IN TURKEY Ergun Ozbudun Ergun Ozbudun is professor <�{ political science at Bilkenr University in Ankara. His publications in.elude Social Change and Political Participation in Turkey (1976) and Contemporary Turkish Politics: Challenges to Democratic Consolidation (2000). Commenting on Turkish politics in the 1950s, Frederick Frey argued that "Turkish politics are party politics .... Within the power structure of Turkish society, the political party is the main unofficial link between the government and the larger, extra-governmental groups of people .... It is perhaps in this respect above all-the existence of extensive, powerful, highly organized, grassroots parties-that Turkey differs institutionally from the other Middle Eastern nations with whom we frequently compare her."1 Since the 1970s, however, Turkey's parties and party system have been undergoing a protracted process of institutional decay, as described in the first section. The party system has been beset by growing fragmentation, ideological polarization, and electoral volatilfry. Parties themselves have been dogged by declining organizational capacity and a lack of public support and identification. The next section will discuss the common organizational characteristics of Turkey's main political parties. I shall argue that, in general, Turkish parties are catch-all and cartel parties. In the following sections, I shall discuss the social, ideological, and organizational characteristics of the Welfare Party (now the Virtue party), the Motherland Party, the True Path Party, the Democratic Left Party, and the Republican People's Party, as well as a few minor parties. Deinstitutionalization, Fragmentation, and Polarization Turkey displayed the characteristics of a typical two-party system between 1946 and 1960, when the two main contenders for power were the Republican People's Party (RPP) and the Democratic Party (OP).