Examining the Price Difference for Chinese A, H and N Shares*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Circular Is Important and Requires Your Immediate Attention

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your stockbroker or other registered dealer in securities, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Fuyao Glass Industry Group Co., Ltd., you should at once hand this circular, together with the accompanying proxy form and the reply slip, to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s) or to the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s). Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. This circular is for information purpose only and does not constitute an invitation or offer to acquire, purchase or subscribe for any securities of the Company. (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 3606) PROPOSED ISSUANCE OF ADDITIONAL H SHARES UNDER SPECIFIC MANDATE AND PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO THE ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION AND CERTAIN CORPORATE GOVERNANCE POLICIES Placing Agent The 2021 second extraordinary general meeting (the “EGM”) of Fuyao Glass Industry Group Co., Ltd. will be held in the conference room of the Company located at Fuyao Industrial Zone, Rongqiao Economic & Technological Development Zone, Fuqing City, Fujian Province, the PRC at 2:00 p.m. -

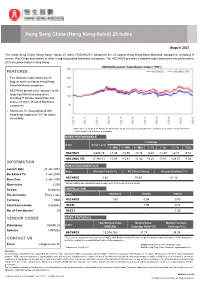

Hang Seng China (Hong Kong-Listed) 25 Index

Hang Seng China (Hong Kong-listed) 25 Index August 2021 The Hang Seng China (Hong Kong- listed) 25 Index ("HSCHK25") comprises the 25 largest Hong Kong-listed Mainland companies, including H shares, Red Chips and shares of other Hong Kong-listed Mainland companies. The HSCHK25 provides a tradable index that tracks the performance of China plays listed in Hong Kong. FEATURES ■ This thematic index tracks the 25 biggest and most liquid Hong Kong- listed Mainland companies ■ HSCHK25 provides an exposure to the large-cap Mainland companies, including H Shares, Red Chips and shares of other HK-listed Mainland companies ■ Stocks are freefloat-adjusted with weightings capped at 10% for higher investibility Data has been rebased at 100.00. All information for an index prior to its launch date is back-tested, back-tested performance reflects hypothetical historical performance. INDEX PERFORMANCE % Change Index Index Level 1 - Mth 3 - Mth 6 - Mth 1 - Yr 3 - Yr 5 - Yr YTD HSCHK25 8,630.19 +1.49 -13.50 -14.18 -0.67 -11.29 +6.71 -9.51 HSCHK25 TRI 17,191.11 +1.80 -11.81 -11.82 +2.47 -0.70 +28.57 -7.02 INFORMATION INDEX FUNDAMENTALS Launch Date 20 Jan 2003 Index Dividend Yield (%) PE Ratio (Times) Annual Volatility*(%) Backdated To 3 Jan 2000 HSCHK25 3.32 10.02 21.12 Base Date 3 Jan 2000 Base Index 2,000 *Annual Volatility was calculated based on daily return for the past 12-month period. Review Quarterly CORRELATION Dissemination Every 2 sec Index HSCHK25 HSCEI HSCCI Currency HKD HSCHK25 1.00 0.98 0.73 Total Return Index Available HSCEI - 1.00 0.73 No. -

Chinese Equities – the Guide March 2021

Chinese equities – the guide March 2021 For professional investors only. In Switzerland for Qualified Investors. In Australia for wholesale clients only. Not for use by retail investors or advisers. Introduction Investors who venture into the Chinese stock universe face an alphabet soup of seemingly random letters. There are A-shares, H-shares and S-chips to name just a few (see Chart 1). These letters represent various attempts to develop the equity market in a country where people traded the first shares as long ago as the 1860s. But something resembling a modern stock market, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, didn’t start operations until 1 December 1990.1 Shenzhen beat Shanghai as the first exchange of the modern era by some three weeks.2 The Hong Kong Stock Exchange, a forerunner to the city’s current bourse, began operations in 1914 but developed under British colonial rule.3 Investors view Hong Kong as a separate and distinct market. Chart 1: Alphabet soup of Chinese equities Shares Listing Currency Country of Country Examples Index inclusion Comments Can Chinese incorporation where investors buy? company does most business A-share Shanghai + Renminbi China China Shanghai CSI 300 or MSCI Some have dual Y Shenzhen International China A Onshore. listing in H-share Airport Co. MSCI EM since market June 2018 B-share Shanghai + US dollar + China China N/A None Interest has Y Shenzhen Hong Kong collapsed since dollar H-shares H-share Hong Kong Hong Kong China China PetroChina, China MSCI China All Often dual listing Y dollar Construction -

Global Offering E

(a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock code : 2120 RESPECTING LIFE HUMBLE SERVICE GLOBAL OFFERING Joint Sponsors (in alphabetical order) Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers IMPORTANT IMPORTANT: If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this Prospectus, you should obtain independent professional advice. Wenzhou Kangning Hospital Co., Ltd. 溫州康寧醫院股份有限公司 (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) GLOBAL OFFERING Number of Offer Shares under the Global Offering : 17,600,000 H Shares (subject to adjustment and the Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares : 1,760,000 H Shares (subject to adjustment) Number of International Offer Shares : 15,840,000 H Shares (subject to adjustment and the Over-allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price : HK$38.7 per H Share, plus brokerage of 1%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027%, and Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars and subject to refund on final pricing) Nominal value : RMB1.00 per H Share Stock code : 2120 Joint Sponsors (in alphabetical order) Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this Prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Prospectus. -

SH-HK Connect: New Regime, Unprecedented Opportunity

September 11, 2014 China Strategy SH-HK Connect: New regime, unprecedented opportunity Portfolio Strategy Research The ‘new’ investment case for China for global/A-share investors SH-HK Stock Connect: Redefining the Chinese equity market Kinger Lau, CFA +852-2978-1224 [email protected] The Connect scheme brings China A to the global arena and potentially Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. unleashes significant portfolio flows from China to HK. We provide a framework for the new market landscape for global and A-share investors. Timothy Moe, CFA +852-2978-1328 [email protected] Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. Global investors: China A is too important to ignore nd rd Ben Bei 1. The scheme creates a single ‘China’ market which ranks as the 2 /3 +852-2978-1220 [email protected] largest globally by cap/turnover, and adds 855 US$1bn companies to the Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. investable universe. 2. China A will likely be included in global benchmarks Chenjie Liu, Ph.D soon, based on Korea’s and Taiwan’s experience. 3. Global investors may +86(10)6627-3324 [email protected] be able to trade China growth more efficiently in China A. Key micro Beijing Gao Hua Securities Company Limited overlays for stock picking may revolve around scarcity value, GDP proxy, , and . high/stable yields, QFII ownership proper management incentive A-share investors: Diversification, undervalued growth in HK The scheme allows Chinese households to diversify their inefficient asset allocation: 72% in property, 6% in equities. Their investment behavior and demand for diversification suggest they may focus on: (1) mid-cap growth stocks, including select dual-listed H on possible re-rating; (2) HK blue chips with global footprint; and (3) household brands not available in A. -

The Mofo Guide to Hong Kong Ipos a COMPLEX SUBJECT MADE SIMPLE

THE MOFO GUIDE TO HONG KONG IPOS A COMPLEX SUBJECT MADE SIMPLE. A WEALTH OF EXPERIENCE. INNOVATIVE IDEAS. PRACTICAL SOLUTIONS. This IS MOFO. LearN MOre at www.MOFO.COM. FOrewORD The transition from private to public ownership is a major step in the lifecycle of a company, involving a complex and often challenging process of dealing with regulators, investors and professional parties, while continuing to run the company’s business. As one of the world’s preeminent international financial centers, Hong Kong has become a destination of choice for many companies seeking to make this transition through an initial public offering (“IPO”) and listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The MoFo Guide to Hong Kong IPOs (“Guide”) aims to help companies and their advisers successfully navigate this transition by providing a comprehensive overview of the IPO process in Hong Kong, with an emphasis on listings on the Main Board of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The Guide covers the IPO process from the preliminary planning stages and pre-IPO considerations all the way up to, and including, a listed company’s post-IPO obligations. The Guide also discusses listing issues pertinent to companies in specific industries, such as mineral and natural resources companies, as well as issues that arise when conducting an international offering to investors in other jurisdictions, such as the United States. Practical tips are included throughout the Guide based on our experience advising on Hong Kong IPOs over the years. While we have tried to make the Guide as informative as possible, please kindly note that it is only an overview of the major legal, regulatory and practical issues involved in the Hong Kong IPO process as of November 5, 2012 and therefore should not be relied upon as legal advice in any jurisdiction. -

Listing PRC Companies in Hong Kong Using VIE Structures

Listing PRC Companies in Hong Kong Using VIE Structures October 2014 www.charltonslaw.com 0 Index Page Executive summary 2 Contents 。 Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx)’s background information 4 。 Introduction to listing of PRC companies on HKEx 15 。 VIE structure 21 。 Key requirement of Main Board listing on HKEx 30 。 Requirements for a listing – Hong Kong vs U.S. 39 About Charltons 46 Disclaimer 47 1 Executive summary Hong Kong market is the 6th largest stock market in the world Hong Kong ranked 3rd worldwide in terms of IPO funds raised (only after NYSE and Nasdaq) in 2013 VIE structures can be listed on The Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) subject to complying with requirements of listing decision ○ certain businesses maybe subject to PRC’s foreign investment restriction if they belong to certain industry sectors (Restricted Industries) ○ Restricted industries include compulsory education, news agencies and internet-related services Key Hong Kong listing requirements: ○ three financial criteria: (1) the profit test ; (2) the market capitalisation/revenue test; or (3) the market capitalisation/revenue/ cashflow test ○ A 3-year track record period requirement is usually applied to a listing applicant * HKEx may also accept a shorter trading record period and/or may vary or waive the financial standards requirements on certain circumstances ○ Maintain at all times a minimum public float of 25% of the Company’s total issued share capital 2 Executive summary Key U.S. listing requirements ○ minimum quantitative requirements, which -

Chinese Cross-Listed Firms

Bachelor thesis 10p Stockholm University August, 2006 Chinese cross-listed firms A study about the relations between cross-listed A & B shares and A & H shares Supervisor: Writers: Dr. Tor Brunzell Han, Na Jokhadar, Nina Taghinejad Namini, Armin 1(39) Abstract: This paper investigates the hidden relations between the Chinese cross-listed firms in the Shanghai and Hong Kong stock exchanges. In China, stocks are classified into four categories: A shares, B shares, H shares and ADR shares. A and B shares are traded on China’s two stock exchanges, namely Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges while H and ADR shares are traded in Hong Kong and the USA respectively. A shareholders consist of mainly domestic investors with a fraction of foreign investors; B shareholders are however, a mixture of Chinese and international shareholders; H and ADR shares are targeted only towards international investors. A firm can only choose to cross-list A and B shares or A and H shares. 21 companies that have cross-listed A and H shares and 44 companies that have cross-listed A and B shares during the timeframe between July, 2001 and June, 2006 have been studied. We have retrieved closing prices on the 20th of every month and using the general mathematical approach involving log-returns, the expected monthly returns, variances and covariances have been estimated. Our results for A and B cross-listed firms show that the monthly returns are in the same and have reasonably high correlations. The results for A and H cross-listed firms however, show that the expected returns of the H shares are of higher magnitude than the A shares and that they show significantly lower correlations. -

SH-HK Stock Connect Information Book for Investor

0 The information contained in this document is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any securities or to provide any investment advice or service of any kind. This document is not directed at, and is not intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (“HKEX”), The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (“SEHK”), Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited, Shenzhen Stock Exchange (“SZSE”), Shanghai Stock Exchange (“SSE”) and China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation Limited (together, the “Entities”, each an “Entity”), or any of their affiliates, or any of their affiliates, or any of the companies that they operate, to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. No section or clause in this document may be regarded as creating any obligation on the part of any of the Entities. Rights and obligations with regard to the trading, clearing and settlement of any securities transactions effected on the SZSE, SSE and SEHK, including through Shanghai Connect or Shenzhen Connect (together “Shanghai and Shenzhen Connect”), shall depend solely on the applicable rules of the relevant exchanges and clearing houses, as well as the applicable laws, rules and regulations of Mainland China and Hong Kong. Although the information contained in this document is obtained or compiled from sources believed to be reliable, none of the Entities guarantee the accuracy, validity, timeliness or completeness of the information or data for any particular purpose, and the Entities and the companies that they operate shall not accept any responsibility for, or be liable for, errors, omissions or other inaccuracies in the information or for the consequences thereof. -

A Glance at the Tax Implications of the Shenzhen – Hong Kong Stock Connect

News Flash China Tax and Business Advisory A Glance at the tax implications of the Shenzhen – Hong Kong Stock Connect December 2016 Issue 39 In brief The Shenzhen –Hong Kong Stock Connect (SZ–HKStock Connect) has been launched on 5 December 2016. It is modelled after the Shanghai –Hong Kong Stock Connect (SH-HK Stock Connect) and offers more opportunities for investors to invest in the China stock markets. The Ministry of Finance (“MOF”), the State Administration of Taxation (“SAT”)and China Securities Regulatory Commission (“CSRC”)jointly released Caishui[2016]No.127 on 2 December 2016 to clarify the China tax policies in relation to the SZ– HK Stock Connect. These China tax policies are similar to those for the SH–HKStock Connect. We hereby summarise the major China tax and Hong Kong tax issues which investors of both sides should be aware of when making investment via this new investment channel. In detail repayment of shares under national strategies, including covered short selling the opening up of its capital Shortly after the SH– HK Stock transactions carried out by market, economic Connect was officially launched Hong Kong/foreign investors transformation and upgrade, on 17 November 2014, the MOF, under the north bound trading strengthening the role of Hong SAT and CSRC jointly released link (for both the SZ– HK Stock Kong as an international Caishui [2014] No.81 setting Connect and SH – HK Stock financial centre and the the China tax policies in Connect) will be temporarily internationalization of RMB. relation to Hong Kong and exempt from stamp duty in The consistent tax policies for Mainland investors which China. -

CHINA PETROLEUM & CHEMICAL CORP Form 20-F Filed 2017-04-24

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 20-F Annual and transition report of foreign private issuers pursuant to sections 13 or 15(d) Filing Date: 2017-04-24 | Period of Report: 2016-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001341004-17-000262 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER CHINA PETROLEUM & CHEMICAL CORP Mailing Address Business Address 22 CHAOYANGMEN NORTH 22 CHAOYANGMEN NORTH CIK:1123658| IRS No.: 000000000 | Fiscal Year End: 1231 STREET STREET Type: 20-F | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-15138 | Film No.: 17778454 CHAOYANG DISTRICT CHAOYANG DISTRICT SIC: 2911 Petroleum refining BEIJING CHINA F4 100728 BEIJING F4 100728 861059960028 Copyright © 2017 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 ______________ FORM 20-F (Mark One) ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2016 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 DATE OF EVENT REQUIRING THIS SHELL COMPANY REPORT ………………. FOR THE TRANSACTION PERIOD FORM ____________ TO __________ COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-15138 ___________________________ 中国石油化工股份有限公司 CHINA PETROLEUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) ____________________________ The People’s Republic of China (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) ____________________________ 22 Chaoyangmen North Street Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100728 The People’s Republic of China (Address of principal executive offices) ____________________________ Mr. -

449910 H Share Eng.Indb

Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management Members Basic Information Incumbent Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management Members Name Year of birth Gender Position Term of offi ce LI Lihui 1952 Male Vice Chairman and President From August 2004 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 LI Zaohang 1955 Male Executive Director and From August 2004 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 Executive Vice President WANG Yongli 1964 Male Executive Director and From February 2012 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2015 Executive Vice President SUN Zhijun 1955 Female Non-executive Director From October 2010 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 LIU Lina 1955 Female Non-executive Director From October 2010 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 JIANG Yansong 1963 Female Non-executive Director From October 2010 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 ZHANG Xiangdong 1957 Male Non-executive Director From July 2011 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2014 ZHANG Qi 1972 Male Non-executive Director From July 2011 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2014 Anthony Francis NEOH 1946 Male Independent Director From August 2004 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 HUANG Shizhong 1962 Male Independent Director From August 2007 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 HUANG Danhan 1949 Female Independent Director From November 2007 to the date of the Annual General Meeting in 2013 CHOW Man Yiu, Paul 1946 Male Independent Director From October 2010 to the date