Transcript of Oral History Interview with John Kaul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GORDON ROSENMEIER the Little Giant from Little Falls

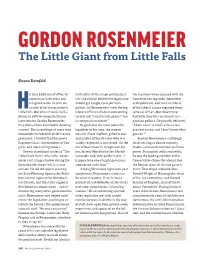

GORDON ROSENMEIER The Little Giant from Little Falls Steven Dornfeld e had been out of office for with either of the major political par- the members who caucused with the more than three years and ties and did not believe the legislature Conservatives regarded themselves relegated to the relative ob- should get caught up in partisan as Republicans, and most members Hscurity of his law practice in politics. In Rosenmeier’s view, the leg- of the Liberal caucus regarded them- Little Falls. But when friends held a islature of his era had an outstanding selves as DFLers. But Rosenmeier dinner in 1974 to recognize former record and “its particular genius” was had little time for— or interest in— state senator Gordon Rosenmeier, its nonpartisan nature.3 partisan politics. He proudly declared, they did not have any trouble drawing Regarded as the most powerful “I have never so much as been to a a crowd. The assemblage of more than legislator of his time, the senator precinct caucus and I don’t know what 800 people included three Minnesota was a brilliant intellect, gifted orator, goes on.”5 governors, a third of the Minnesota and master of Senate rules who was Second, Rosenmeier— although Supreme Court, two members of Con- widely respected, if not feared. On the never serving as Senate majority gress, and scores of legislators.1 eve of Rosenmeier’s recognition din- leader— amassed enormous political Known in political circles as “The ner, former Republican Gov. Harold power. During the 1950s and 1960s, Little Giant from Little Falls,” Rosen- LeVander said, only partly in jest, “I he was the leading member of the meier cast a huge shadow during his happen to be one of eight governors Conservative clique that dominated three decades (1940–70) as a state who served under him.”4 the Senate, if not all of state govern- senator. -

Clccatalog2018-20(Pdf)

About the College Central Lakes College – Brainerd and Staples is one of 37 Minnesota State Colleges and Universities, offering excellent, affordable education in 54 communities across the state. We are a comprehensive community and technical college serving about 5,500 students per year. With a knowledgeable, caring faculty and modern, results-oriented programs in comfortable facilities, CLC is the college of choice for seekers of success. Our roots are deep in a tradition dating to 1938 in Brainerd and 1950 in Staples. Communities across central Minnesota are filled with our graduates. Central Lakes College (CLC) begins making an impact early, meeting each student at different points along their educational journey and helping them toward their chosen pathway. A robust concurrent enrollment program, well-tailored technical programs, and an associate of arts degree enables a student to start at CLC, saving time and money. Students who have earned the associate’s degree may then elect to transfer to any Minnesota State four-year college or university. The range of options for students at CLC is unique to the region and includes more than 70 program selections that will jumpstart career opportunities after graduation. Home to the North Central Regional Small Business Development Center, CLC is the center of economic development helping young businesses thrive, while it remains at the cutting edge of farm research through its Ag and Energy Center. Mission: We build futures. At Central Lakes College, we- • provide life-long learning opportunities in Liberal Arts, Technical Education, and Customized Training programs; • create opportunities for cultural enrichment, civic responsibility, and community engagement; and • nurture the development and success of a diverse student body through a respectful and supportive environment. -

People-‐Powered Policy

People-Powered Policy: 60 Years of preserving MN’s natural heritage Sen. Dave Durenberger My goal tonight is to express what it means to me to be a Minnesotan. Not the one who starts every day and every conversation with a weather report—or, as we age, with a five-minute health status report. Rather the person who learned early in his life, and had reinforced along its personal and professional path, what it means to build on the gift of life here: a better future for our children, our grandchildren and our neighbors. I am reminded from my perch here in my 80th year, of how Minnesota became a world leader in preserving the natural heritage that drew our Native American forbearers to this land in the first place. They remain here to remind us of their heritage. That also is the story of the Parks and Trails Council of Minnesota I was asked to help you celebrate this evening. Minnesota is not famous for its oceans, its mountains or its Golden Gate, but rather for what people like you and I would become here. Those who were our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents brought a unique culture to the prairie, Big Woods and lakes state that is Minnesota. The history of this state has evolved from the frugal Yankee entrepreneurs of New England, with their Calvinist conscience and civic virtue, who met up here with northern and eastern European immigrants. People like my great-grandfather, who on the family tree in a farmhouse just north of the Boden See in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, is listed as “Gephard Durrenberger, May 21, 1859— Gone to America.” These immigrant men and women were frugal, of necessity. -

Interview with Winston Borden August 7, 1973 Central Minnesota Historical Oral History Collection St

Interview with Winston Borden August 7, 1973 Central Minnesota Historical Oral History Collection St. Cloud State University Archives Interviewed by Calvin Gower This is an interview conducted by Calvin Gower for the Central Minnesota Historical Center on August 7, 1973. Today I am interviewing Winston Borden, State Senator from District 13, elected in 1970 and serving in the Senate at the present time. Gower: Okay, Winston, would you tell us when you were born, where you were born, something about your family background and your education. Borden: I was born December 1, 1943 in Brainerd, Minnesota. I grew up on a farm in the northern part of Crow Wing County, which is currently part of my senate district. My family has been in this area since about 1880. I attended Brainerd Public Schools and I graduated from Washington High School in 1961. I received a B.A. degree with majors in social science and public address from St. Cloud State College in 1965. I received a master’s degree in government administration and juris doctorate from the University of Minnesota Law School in 1968. Gower: What was your family background? Borden: My father had an elementary school education and has farmed all of his life in the district. My mother is a high school graduate. I have two brothers, one of whom runs a family 1 farm, another of whom is engaged in the practice of law with me, and a sister who is a housewife. Gower: Was your father ever involved in politics at all? Borden: Politics was always a subject of discussion around the family dinner table. -

LEGISLATURE an Inventory of the Videotapes and Audio Cassettes Compiled for Tribune of the People

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Minnesota State Archives LEGISLATURE An Inventory of the Videotapes and Audio Cassettes Compiled for Tribune of the People Access to or use of this collection is currently restricted. For Details, see the Restrictions Statement OVERVIEW OF THE RECORDS Agency: Minnesota. Legislature. Series Title: Videotapes and audio cassettes compiled for Tribune of the People. Dates: 1978-1986. Abstract: Materials collected during the research for Royce Hanson's book, Tribune of the People: The Minnesota Legislature and Its Leaders. Quantity: 2.2 cu. ft. (2 boxes and 1 half-height oversize box). Location: See Detailed Description section for box locations. SCOPE AND CONTENTS OF THE RECORDS The series’ first section includes two television videotapes, the first containing the May 30, 1986 Almanac, KTCA's weekly public affairs program, featuring host Joe Summers, political consultant D. J. Leary, lobbyist Wyman Spano, and analyst Kris Sanda interviewing Perpich campaign chairman Tom Berg, KTCA general manager Dick Moore, Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs' Royce Hanson, and Senator Rudy Boschwitz. The second videotape contains the January 4 and December 28, 1978 and April 14, 1980 Minnesota Issues, hosted by Arthur Naftalin and sponsored by the Humphrey Institute and the University of Minnesota's Center for Urban and Regional Affairs. Featured are Senate Majority Leader Nicholas D. Coleman, Minority Leader Robert O. Ashbach, and House Speaker Rod Searle. Topics include tax cuts, campaign financing, special elections, abortion, higher education, "ban the can" legislation, partisan relationships, appointments, officer elections, staff, and the declining number of legislators seeking re-election. The second section consists of legislative interviews conducted mainly with formal and informal leaders of the State Legislature who served between 1962 and 1986. -

Little Falls' Historic Contexts

Little Falls‘ Historic Contexts Final Report of an Historic Preservation Planning Project Submitted to the Little Falls Heritage Preservation Commission And the City of Little Falls July 1994 Prepared by: Susan Granger and Scott Kelly Gemini Research Morris, MN 56267 Little Falls’ Historic Contexts Final Report of an Historic Preservation Planning Project Submitted to the Little Falls Heritage Preservation Commission And the city of Little Falls July 1994 Prepared by Susan Granger and Scott Kelly Gemini Research, Morris Minnesota This project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the Minnesota Historical Society under the provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act as amended. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendations by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental federally assisted Programs based on race, color, national origin, age, or handicap. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, PO Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Table of Contents I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………..01 II. Historic Contexts……………………………………………………………05 III. Native Americans and Euro-American Contact…………....…...05 Transportation………………………………………………….………17 Logging…………………………………………………………………...29 Agriculture and Industry……………………………………….…...39 Commerce………………………………………………….….………….53 Public and Civic Life…………………………………..……………….61 Cultural Development………………………………………………...73 Residential Development…………………………..…….………….87 IV. -

Minnesota State Capitol: Overview of the Fine Art

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota State Capitol: Overview of the Fine Art 2015 Minnesota State Capitol: Overview of the Fine Art 2015 An Overview of the Original Art in the Minnesota State Capitol In the planning and construction of Minnesota’s third state capitol building from 1896- 1905, Cass Gilbert, its architect, had envisioned the exterior having statuary in marble and bronze and interior spaces decorated with impressive works of art. His inspiration was not only from trips to Europe but directly influenced by a pivotal event in United States history, the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago World’s Fair) of 1893. The Fair not only presented new technological advancements and wonders, but it opened the door to a new generation of architects and artists who oversaw the construction and decoration of what became known as “The White City.” Trained in classical architecture and art, in particular at the Ecole des Beaux Art in Paris, the goal of these professionals was to revive the features and themes of the Italian Renaissance into public buildings. Through the use of Classical symbolism and allegory, the art was designed to inspire and educate the visitor. The construction of the Library of Congress (Jefferson Building) in the mid-1890s was the first test case after the fair which captured in large scale, that Beaux Art philosophy. It was a resounding success and set the direction in public architecture for the next forty years. -

The Minnesota Senate Week in Review

r-Z '-I / This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library I as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp The Minnesota Senate Week in Review 12,1988 75th Session reconvenes Workers' comp system reviewed The Senate convened at 2:00 p.m., Thesday, February 9, 1988, to The Employment Subcommittee on Injured \V'orkers met open the second half of the 75th Legislative Session. Monday, February 8, to hear reports from Leslie Altman, a Workers' Following a prayer by the Senate chaplain, Reverend Philip Compensation Court ofAppeals judge and Duane Harves, chief \'?eiler, the Senate approved opening day resolutions adopted by the . administrative law judge ofthe Minnesota Office ofAdministrative Rules and Administration Committee. Hearings. Each speaker presented statistical data on workers' Seventy-seven bills were read for the first time and referred to the compensation cases handled by the legal offices. appropriate committees. Elliot Lang, deputy legislative auditor coordinator, also spoke, Senate l\'Iajority Leader Roger Moe (DFL-Erskine) informed the offering highlights of a comprehensive report on the workers' members that the Senate and House would meet in a joint session, compensation system which will be presented in its entirety early Thursday, February 11, to observe a presentation by an actor this session. The 1987 Legislature commissioned the study portraying Thomas Jefferson. The performance has been seen by The subcommittee is chaired by Sen, A,'ll "Bill" Diessner (DFL several other state legislatures, Moe said. Afton). Governor delivers State ofthe State Legislative priorities outlined Minnesota is in good shape, and will continue to improve, On Monday, February 8, the Minnesota Association ofTmvnships Governor Rudy Perpich said during the State ofthe State speech and the Association of Minnesota Counties presented their 1988 111esday, February 9. -

Minnesota Politics and Irish Identity Carolyn J

Minnesota Politics RAMSEY COUNTY and Irish Identity: Five Sons of Erin at the State Capitol HıstoryA Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society John W. Milton —Page 3 Spring 2009 Volume 44, Number 1 Five Sons of Erin at the Minnesota State Capitol (clockwise from Minnesota Historical Society); Governor Andrew Ryan McGill, 1889 the upper right): Senator Nicholas D. Coleman (bronze bust by (oil portrait by Carl Gutherz; courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Paul T. Granlund, 1983; photo by Robert W. Larson, 2009); Ignatius Society); and General James Shields, about 1860 (oil portrait by Donnelly, 1891 (oil portrait by Nicholas Richard Brewer; courtesy Henry W. Carling; courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society). In of the Minnesota Historical Society); Archbishop John Ireland, the background is a postcard of the Minnesota State Capitol from about 1910 (pastel portrait by an anonymous artist; courtesy of the about 1907 (postcard courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society). RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY RAMSEY COUNTY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 44, Number 1 Spring 2009 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY the mission statement of the ramsey county historical society BOARD OF DIRECTORS adopted by the board of directors on December 20, 2007: J. Scott Hutton The Ramsey County Historical Society inspires current and future generations Past President Thomas H. Boyd to learn from and value their history by engaging in a diverse program President of presenting, publishing and preserving. Paul A. Verret First Vice President Joan Higinbotham Second Vice President C O N T E N T S Julie Brady Secretary 3 Minnesota Politics and Irish Identity Carolyn J. -

Justice John E. Simonett: 1924–2011 Martha M

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 39 | Issue 3 Article 12 2013 Justice John E. Simonett: 1924–2011 Martha M. Simonett Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Simonett, Martha M. (2013) "Justice John E. Simonett: 1924–2011," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 39: Iss. 3, Article 12. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol39/iss3/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Simonett: Justice John E. Simonett: 1924–2011 JUSTICE JOHN E. SIMONETT: 1924 – 2011 † Honorable Martha M. Simonett Dad was born on July 12, 1924, at a Mankato hospital and grew up in nearby Le Center, Minnesota, with his mother, Veronica Moudry, his father, Edward, and his sister, Mary Therese. He graduated from St. John’s University (magna cum laude) in 1948, with time out for military service (November 1944 to September 1946), including time in the Philippines as a First Lieutenant, Infantry. He met my mother, Doris Bogut, who attended the College of St. Benedict, during his college years at St. John’s University. After college, he graduated from the University of Minnesota Law School (magna cum laude) in 1951, where he was a member of the Order of the Coif and president of the Minnesota Law Review. He and Mom were married that same year in Hudson, Wisconsin, Mom’s hometown, and moved to Little Falls, Minnesota, where they raised six children. -

Operation Save a Duck and the Legacy of Minnesota's 1962-63 Oil Spills

Operation Save A Duck AND THE LEGACY OF MINNESOTA’S 1962–63 OIL SPILLS Stephen J. Lee A canvasback duck immobilized by soybean oil near Hastings; thick oil trails in the Mississippi River near South St. Paul, April 1, 1963. Catastrophes often trigger Duck. These events spurred some of workers left for the evening, they advances in environmental protec- the state’s earliest legislative debate neglected to close the valve between tion. This was true in Minnesota in on controlling pollution to protect the pipeline and a large aboveground the winter of 1962–63, when more the environment. storage tank. They also forgot to than three million gallons of soybean The winter of 1962–63 was cold. open steam lines that kept the oil in oil spilled in Mankato and flowed On Friday, December 7, 1962, work- the pipeline warm and flowing.1 down the Minnesota River to join ers at the Richards Oil Company During the weekend, when even - more than one million gallons of plant on the Minnesota River in ing temperatures dipped below zero, industrial oil spilled in Savage. The Savage pumped “cutter” oil from rail the uninsulated, unheated pipe con- gooey mess killed an estimated cars into a storage tank through a tracted and broke in three places. 10,000 ducks near Red Wing and long, 10-inch-diameter steel pipe - Some one million gallons of oil, the Hastings and prompted Governor line. (Cutter oil is thin, like kerosene entire contents of the tank, drained Karl Rolvaag to activate the National or diesel fuel, and used to make from the broken pipeline over 30 Guard in the futile Operation Save a heavy oils pumpable.) When the acres of ground.2 105 Because the family-owned Agency or a state Pollution Control powerful force of escaping oil Richards plant was unstaffed during Agency, it was the Department of pushed the hull of the big tank back- the weekend, the spill was not dis- Health’s Water Pollution Control ward into five smaller tanks contain- covered until Monday morning. -

SESSION WEEKLY a Nonpartisan Publication of the Minnesota House of Representatives ♦ January 31, 1997 ♦ Volume 14, Number 4

SESSION WEEKLY A Nonpartisan Publication of the Minnesota House of Representatives ♦ January 31, 1997 ♦ Volume 14, Number 4 HF160-HF342 Session Weekly is a nonpartisan publication of the Minnesota House of SESSION WEEKLY Representatives Public Information Office. During the 1997-98 Legislative Minnesota House of Representatives • January 31, 1997 • Volume 14, Number 4 Session, each issue reports daily House action between Thursdays of each week, lists bill introductions and upcoming committee meeting schedules, and pro- vides other information. The publication Update is a service of the Minnesota House. The Legislature has only met in session for one month now, but the average No fee. population has increased dramatically throughout the Capitol and State Office Build- ings. Activists, constituents, and lobbyists have converged on the complex to share To subscribe, contact: information and try and help to play a role in legislative decision-making. Minnesota House of Representatives While such issues as a new stadium for the Minnesota Twins or more money for Public Information Office 175 State Office Building education are being brought to the table, some of the 134 House members have already St. Paul, MN 55155-1298 introduced 342 bills that received a first reading. All of these have been sent to House (612) 296-2146 or committees for hearings. Only four bills have been sent back to the body and passed. 1-800-657-3550 So far, no bills have failed to pass. About 1,500 bills will be introduced by the end of TTY (612) 296-9896 May, but only some 300 may go to the governor to be signed into law, and some of them may be vetoed.