The Distinguished Life & Work of the Honorable John E. Simonett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Session: Annual Hennepin County 2021 Bar Memorial

State of Minnesota District Court County of Hennepin Fourth Judicial District Special Session: Annual Hennepin County 2021 Bar Memorial Convening of the Special Session of Hennepin County District Court Chief Judge Toddrick S. Barnette Presiding Invocation The Honorable Martha A. Holton Dimick Hennepin County District Court Introduction of Special Guests Recognition of Deceased Members Brandon E. Vaughn, President-Elect Hennepin County Bar Association Remarks and Introduction of Speaker Esteban A. Rivera, President Hennepin County Bar Association Memorial Address Justice Natalie E. Hudson Minnesota Supreme Court Musical Selection Lumina Memorials Presented to the Court Kathleen M. Murphy Chair, Bar Memorial Committee Presentation Accepted Court Adjourned Music by Laurie Leigh Harpist April 30, 2021 Presented by the Hennepin County Bar Association in collaboration with the Hennepin County District Court ABOUT THE BAR MEMORIAL The Hennepin County Bar Association and its Bar Memorial Committee welcome you to this Special Session of the Hennepin County District Court to honor members of our profession with ties to Hennepin County who passed away. We have traced the history of our Bar Memorial back to at least 1898, in a courthouse that is long gone, but had a beauty and charm that made it a fitting location for this gathering. We say “at least 1898,” because there is speculation that the practice of offering annual unwritten memorials began in 1857. Regardless of its date of origin, the Bar Memorial is now well into its second century, and it is a tradition that is certain to continue simply because it is right— and it is good. Buildings come and go, but the Bar Memorial has always found a suitable home, including in the chambers of the Minneapolis City Council, the boardroom of the Hennepin County Commissioners, and in Judge James Rosenbaum’s magnificent courtroom. -

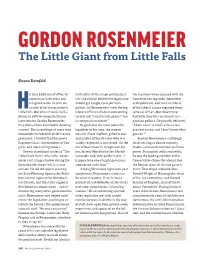

GORDON ROSENMEIER the Little Giant from Little Falls

GORDON ROSENMEIER The Little Giant from Little Falls Steven Dornfeld e had been out of office for with either of the major political par- the members who caucused with the more than three years and ties and did not believe the legislature Conservatives regarded themselves relegated to the relative ob- should get caught up in partisan as Republicans, and most members Hscurity of his law practice in politics. In Rosenmeier’s view, the leg- of the Liberal caucus regarded them- Little Falls. But when friends held a islature of his era had an outstanding selves as DFLers. But Rosenmeier dinner in 1974 to recognize former record and “its particular genius” was had little time for— or interest in— state senator Gordon Rosenmeier, its nonpartisan nature.3 partisan politics. He proudly declared, they did not have any trouble drawing Regarded as the most powerful “I have never so much as been to a a crowd. The assemblage of more than legislator of his time, the senator precinct caucus and I don’t know what 800 people included three Minnesota was a brilliant intellect, gifted orator, goes on.”5 governors, a third of the Minnesota and master of Senate rules who was Second, Rosenmeier— although Supreme Court, two members of Con- widely respected, if not feared. On the never serving as Senate majority gress, and scores of legislators.1 eve of Rosenmeier’s recognition din- leader— amassed enormous political Known in political circles as “The ner, former Republican Gov. Harold power. During the 1950s and 1960s, Little Giant from Little Falls,” Rosen- LeVander said, only partly in jest, “I he was the leading member of the meier cast a huge shadow during his happen to be one of eight governors Conservative clique that dominated three decades (1940–70) as a state who served under him.”4 the Senate, if not all of state govern- senator. -

Clccatalog2018-20(Pdf)

About the College Central Lakes College – Brainerd and Staples is one of 37 Minnesota State Colleges and Universities, offering excellent, affordable education in 54 communities across the state. We are a comprehensive community and technical college serving about 5,500 students per year. With a knowledgeable, caring faculty and modern, results-oriented programs in comfortable facilities, CLC is the college of choice for seekers of success. Our roots are deep in a tradition dating to 1938 in Brainerd and 1950 in Staples. Communities across central Minnesota are filled with our graduates. Central Lakes College (CLC) begins making an impact early, meeting each student at different points along their educational journey and helping them toward their chosen pathway. A robust concurrent enrollment program, well-tailored technical programs, and an associate of arts degree enables a student to start at CLC, saving time and money. Students who have earned the associate’s degree may then elect to transfer to any Minnesota State four-year college or university. The range of options for students at CLC is unique to the region and includes more than 70 program selections that will jumpstart career opportunities after graduation. Home to the North Central Regional Small Business Development Center, CLC is the center of economic development helping young businesses thrive, while it remains at the cutting edge of farm research through its Ag and Energy Center. Mission: We build futures. At Central Lakes College, we- • provide life-long learning opportunities in Liberal Arts, Technical Education, and Customized Training programs; • create opportunities for cultural enrichment, civic responsibility, and community engagement; and • nurture the development and success of a diverse student body through a respectful and supportive environment. -

Application for the Position Member

Application for the position Member Part I: Position Sought Agency Name: Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board Position: Member Part II: Applicant Information Name: George William Soule Phone: (612) 251-5518 County: Hennepin Mn House District: 61B US House District: 5 Recommended by the Appointing Authority: True Part III: Appending Documentation Cover Letter and Resume Type File Type Cover Letter application/pdf Resume application/pdf Additional Documents (.doc, .docx, .pdf, .txt) Type File Name No additional documents found. Veteran: No Answer Part V: Signature Signature: George W. Soule Date: 2/15/2021 2:08:59 PM Page 1 of 1 February 2021 GEORGE W. SOULE Office Address: Home Address: Soule & Stull LLC 4241 E. Lake Harriet Pkwy. Eight West 43rd Street, Suite 200 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 Work: (612) 353-6491 Cell: (612) 251-5518 E-mail: [email protected] LEGAL EXPERIENCE SOULE & STULL LLC, Minneapolis, Minnesota Founding Partner, Civil Trial Lawyer, 2014- BOWMAN AND BROOKE LLP, Minneapolis, Minnesota Founding Partner, Civil Trial Lawyer, 1985-2014 Managing Partner (Minneapolis office), 1996-1998, 2002-2004, 2007-10 TRIBAL COURT JUDGE White Earth Court of Appeals, 2012 - Prairie Island Indian Community Court of Appeals, 2016 - Fond du Lac Band Court of Appeals, 2017- Lower Sioux Indian Community, 2017 - GRAY, PLANT, MOOTY, MOOTY & BENNETT, Minneapolis, Minnesota Associate, Litigation Department, 1979-1985 Admitted to practice before Minnesota courts, 1979, Wisconsin courts, 1985, United States -

Assessing the Changing Nature of Authority in the Web Age: the Citation Practices of Minnesota Supreme Court

Assessing the Changing Nature of Authority in the Web Age: The Citation Practices of Minnesota Supreme Court Rebecca Sherman Submitted to Professor Penny A. Hazelton to fulfill course requirements for Current Issues in Law Librarianship, LIS 595, and to fulfill the graduation requirement of the Culminating Experience Project for MLIS University of Washington Information School Seattle, Washington May 13, 2013 I. INTRODUCTION It has been twenty years since researches gave up the right to patent the World Wide Web and made the source code publicly available.1 Since entering the public domain, the web has revolutionized the way people get information. Although electronic databases such as Westlaw and Lexis have been around since the 70s, they have been transformed to keep pace with developments on the web. Google searching has become so popular that electronic databases are now being redesigned to emulate Google.2 Consider the Google-like search boxes in WestlawNext and Lexis Advance. As a result of the web and increasingly sophisticated databases, attorneys today no longer need to sift through heaps of books at the library. They have virtual access to information anytime and anywhere. Law is a profession that is highly dependent on information. The medium through which information is conveyed undoubtedly has effects on the way the law is understood. Where legal information once existed in a self-contained domain, today it can be found online amidst a universe of information.3 This change of access has raised some concerns. Professor Ellie -

Get Document

State of Minnesota Canvassing Report Report of the Votes Cast for Federal Partisan Offices, State Partisan Offices, and State Judicial Offices At the State General Election held Tuesday, November 2, 2010 Compiled from the Statements of the County Canvassing Boards and Incorporating the Changes to the Votes Counted For Candidates for Offices Reviewed at the 2010 Post Election Review Held in All the Counties of Minnesota Minnesota State Canvassing Report State General Election Tuesday, November 2, 2010 Minnesota Voter Statistics County Registered as of Registered on Absentee Ballots Absentee Ballots Absentee Ballots Total Voting 7am Election Day Regular Federal Only Presidential AITKIN 10,160 517 644 3 0 7,425 ANOKA 193,058 12,434 5,848 45 0 131,703 BECKER 18,865 941 938 0 0 11,904 BELTRAMI 24,832 1,982 1,028 4 0 16,187 BENTON 20,987 1,658 572 0 0 13,827 BIG STONE 3,594 98 159 2 0 2,233 BLUE EARTH 38,456 3,315 1,137 2 0 22,565 BROWN 14,706 1,092 586 1 0 10,517 CARLTON 19,785 1,110 725 4 0 13,780 CARVER 53,165 3,607 1,943 1 0 37,198 CASS 17,978 950 1,170 1 0 13,081 CHIPPEWA 7,164 393 272 0 0 4,905 CHISAGO 31,252 2,283 1,175 2 0 22,990 CLAY 31,100 2,530 1,082 3 0 19,273 CLEARWATER 4,779 336 231 0 0 3,590 COOK 3,467 156 275 2 0 2,858 COTTONWOOD 6,469 410 262 0 0 4,657 CROW WING 38,079 2,580 2,367 15 0 27,658 DAKOTA 237,746 16,316 10,426 28 0 162,919 DODGE 10,906 967 284 1 0 7,988 DOUGLAS 23,234 1,149 1,306 0 0 15,669 11/22/2010 7:44:33 AM Page 1 of 172 FARIBAULT 8,860 533 369 1 0 6,595 FILLMORE 12,757 869 352 0 0 8,466 FREEBORN 18,716 1,003 -

The Minimalist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court1

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 37 | Issue 2 Article 10 2011 Rocks rather than Cathedrals: The inimM alist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court Carol Weissenborn Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Weissenborn, Carol (2011) "Rocks rather than Cathedrals: The inimM alist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 37: Iss. 2, Article 10. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Weissenborn: Rocks rather than Cathedrals: The Minimalist Architecture of the ROCKS RATHER THAN CATHEDRALS: THE MINIMALIST ARCHITECTURE OF THE MINNESOTA SUPREME COURT1 Carol Weissenborn† I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 883 II. BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 884 A. A Voting Bloc .................................................................... 884 B. A Distinct Philosophy ........................................................ 886 III. STATE V. PECK: WORDS AS ROCKS ........................................... 891 IV. BRAYTON V. PAWLENTY: REORDERING THE ROCKS .................. 896 -

Chief Justice Russell A. Anderson Sue K. Dosal, State Court Administrator Minnesota Judicial Branch 2007 Report to the Community

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota Judicial Branch 2007 Report to the Community Chief Justice Russell A. Anderson Sue K. Dosal, State Court Administrator 2007 Report to the Community From the Chief Justice On behalf of our dedicated staff and judges of the Minnesota Judicial Branch, we are pleased to offer this 2007 Report to the Community. In this report you will find many examples of innovation, of the challenges facing our courts, and of our efforts to make Minnesota’s courts, acclaimed internationally for efficiency and administrative and judicial excellence, even better. Minnesota’s trial and appellate courts were united and fully state funded in 2005, and a new governance body, the Judicial Council was created. We are using the benefit of this unification to improve efficiency across the system, reduce costs, enhance service to citizens, promote innovation, and share knowledge across the nearly 100 courts and work sites that make up the Minnesota Judicial Branch. In 2006, the Judicial Council adopted a strategic plan that established goals for the court system around three over-arching themes: (1) Improving Access to Justice; (2) Administering Justice for Effective Results; and (3) Ensuring Public Trust, Accountability and Impartiality. The strategic plan outlines 10 priorities for the 2007- 2009 time period that target court system resources toward advancement in these key areas. One of the most serious challenges facing the Judicial Branch involves our goal of preserving and enhancing public trust and confidence in the court system. -

June 20, 2017 the Honorable Amy Klobuchar United States Senate

June 20, 2017 The Honorable Amy Klobuchar The Honorable Al Franken United States Senate United States Senate 1200 Washington Avenue South, #250 60 Plato Boulevard, #220 Minneapolis, MN 55415 St. Paul, MN 55107 The Honorable Chuck Grassley The Honorable Diane Feinstein United States Senate United States Senate 135 Hart Senate Office Building 331 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Chuck Schumer United States Senate United States Senate 317 Russell Senate Office Building 322 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 Re: Nomination of Justice David Stras to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals Dear Senators: The undersigned are Minnesota lawyers from all political walks of life who join in respectfully urging the Senate to confirm Justice David Stras’s nomination to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. (Signatories’ affiliations are provided for ease of identification and imply neither endorsement nor lack thereof by the affiliated organization.) In his seven years as a Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, Justice Stras has distinguished himself not only as a top-notch jurist, but as a judge who decides cases without regard to political affiliation or party lines. He has sided with both “liberal” and “conservative” Justices during his tenure on the court, always in pursuit of applying the law as it comes to him, without ideology or favoritism. Justice Stras has also proven to be a collegial and collaborative judge, as three of his former colleagues on the Minnesota Supreme Court (retired Justices Alan Page, Helen Meyer, and Paul Anderson) explained in publicly endorsing him in a recent editorial in the Minneapolis StarTribune. -

News Release

OFFICE OF GOVERNOR TIM PAWLENTY 130 State Capitol ♦ Saint Paul, MN 55155 ♦ (651) 296-0001 NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Brian McClung January 3, 2007 (651) 296-0001 GOVERNOR PAWLENTY APPOINTS KASBOHM TO FORENSIC LABORATORY ADVISORY BOARD Saint Paul – Governor Tim Pawlenty today announced the appointment of Lieutenant Brian Kasbohm, commander of the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office Crime Laboratory, to the Forensic Laboratory Advisory Board. Prior to becoming commander of the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office Crime Laboratory, Kasbohm, of Chanhassen, held positions of laboratory supervisor, crime scene section supervisor, bloodstain pattern analyst, as well as over a decade of experience in the crime scene and latent fingerprint sections of the crime lab. He was also the project manager for the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office Crime Laboratory accreditation with the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board. Kasbohm is a member of the American Society of Crime Lab Directors, Association of Forensic Quality Assurance Managers, and International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts. Kasbohm is appointed to a position for an individual with expertise in the field of forensic science and will serve a four-year term that expires on July 1, 2010. The Forensic Laboratory Advisory Board was created by the Legislature (Laws of Minnesota 2006, Chapter 260, Article 3) to develop and implement a reporting system through which laboratories, facilities, or entities that conduct forensic analyses report negligence or misconduct that substantially affects the integrity of the forensic results committed by employees or contractors; encourage reporting of misconduct; investigate allegations of misconduct; and encourage laboratory accreditation with the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board. -

Sam Hanson of Counsel

Sam Hanson Of Counsel 2200 IDS Center 80 South Eighth Street Minneapolis, MN 55402 p: 612.977.8525 f: 612.977.8650 [email protected] Sam Hanson is a member of the firm's Business Litigation and PRACTICE AREAS Energy sections and Appellate practice group. After serving on the Business Litigation Minnesota Court of Appeals for two years and the Minnesota Appellate Representation Supreme Court for five years, he rejoined Briggs and Morgan. Sam is Alternative Dispute a former firm president, managing partner and vice president, as well Resolution (ADR) as former head of the Business Litigation section and a former Energy Litigation member of the board of directors. Sam practices principally in the Energy Law areas of: ● Arbitration and mediation INDUSTRIES Energy ● Complex civil litigation ● Appellate law EDUCATION William Mitchell College of ● Public utility regulation Law, LL.B, 1965, Cum Laude, With Honors Sam's representative cases include: St. Olaf College, B.A., ● Davies v. Waterstone Capital Management, LP, 856 N.W.2d 1961 711 (Minn. Ct. App. 2015) (further review denied, Minnesota Supreme Court; cert. denied U.S. Supreme Court); BAR & COURT successfully reversed district court decision and vacated ADMISSIONS arbitration award of $11 million arising from the termination of Minnesota a high performing trader for our hedge fund client. U.S. District Court District of Minnesota ● In Re Estate of Boyd, 2016 WL76444 (Minn. Ct. App. 2016); U.S. Court of Appeals 8th successfully reversed district court decision dismissing Circuit stepson’s objections to stepfather’s will, which did not honor U.S. Supreme Court the deceased mother’s wishes that her husband devise her previously separate property to her son after her husband’s CLERKSHIPS death. -

People-‐Powered Policy

People-Powered Policy: 60 Years of preserving MN’s natural heritage Sen. Dave Durenberger My goal tonight is to express what it means to me to be a Minnesotan. Not the one who starts every day and every conversation with a weather report—or, as we age, with a five-minute health status report. Rather the person who learned early in his life, and had reinforced along its personal and professional path, what it means to build on the gift of life here: a better future for our children, our grandchildren and our neighbors. I am reminded from my perch here in my 80th year, of how Minnesota became a world leader in preserving the natural heritage that drew our Native American forbearers to this land in the first place. They remain here to remind us of their heritage. That also is the story of the Parks and Trails Council of Minnesota I was asked to help you celebrate this evening. Minnesota is not famous for its oceans, its mountains or its Golden Gate, but rather for what people like you and I would become here. Those who were our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents brought a unique culture to the prairie, Big Woods and lakes state that is Minnesota. The history of this state has evolved from the frugal Yankee entrepreneurs of New England, with their Calvinist conscience and civic virtue, who met up here with northern and eastern European immigrants. People like my great-grandfather, who on the family tree in a farmhouse just north of the Boden See in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, is listed as “Gephard Durrenberger, May 21, 1859— Gone to America.” These immigrant men and women were frugal, of necessity.