Great Gull Island (Sound Update, Summer 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Old Army: Harry K Hollenbach at Fort Robinson, 1911-1913

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: In the Old Army: Harry K Hollenbach at Fort Robinson, 1911-1913 Full Citation: Thomas R Buecker, "In the Old Army: Harry K Hollenbach at Fort Robinson, 1911-1913," Nebraska History 71 (1990): 13-22. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1990Hollenbach.pdf Date: 1/29/2014 Article Summary: Harry K Hollenbach enlisted in the Army early in 1911, spent thirty days at Fort Slocum and was then assigned to the Twelfth Cavalry. At that time he was sent to Fort Robinson. Sixty years later, Hollenbach wrote a memoir of his military experiences, recalling how the new soldiers traveled by rail westward to their new station and what life was like there. This article presents those reminiscences. Cataloging Information: Names: Harry K Hollenbach, Jay K Hollenbach, Charles J Nickels Jr, William F "Buffalo Bill" Cody, Nelson Miles, Horatio Sickel, E -

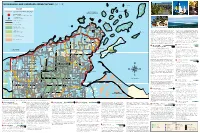

WLSSB Map and Guide

WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY (WLSSB) DEVILS ISLAND NORTH TWIN ISLAND MAP KEY ROCKY ISLAND SOUTH TWIN ISLAND CAT ISLAND WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY APOSTLE ISLANDS BEAR ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE KIOSK LOCATION IRONWOOD ISLAND SCENIC BYWAY NEAR HERBSTER SAILING ON LAKE SUPERIOR LOST CREEK FALLS KIOSKS CONTAIN DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT EACH LOCATION SAND ISLAND VISITOR INFORMATION OUTER ISLAND YORK ISLAND SEE REVERSE FOR COMPLETE LIST µ OTTER ISLAND FEDERAL HIGHWAY MANITOU ISLAND RASPBERRY ISLAND STATE HIGHWAY COUNTY HIGHWAY 7 EAGLE ISLAND NATIONAL PARKS ICE CAVES AT MEYERS BEACH BAYFIELD PENINSULA AND THE APOSTLE ISLANDS FROM MT. ASHWABAY & NATIONAL FOREST LANDS well as a Heritage Museum and a Maritime Museum. Pick up Just across the street is the downtown area with a kayak STATE PARKS K OAK ISLAND STOCKTON ISLAND some fresh or smoked fish from a commercial fishery for a outfitter, restaurants, more lodging and a historic general & STATE FOREST LANDS 6 GULL ISLAND taste of Lake Superior or enjoy local flavors at one of the area store that has a little bit of everything - just like in the “old (!13! RED CLIFF restaurants. If you’re brave, try the whitefish livers – they’re a days,” but with a modern flair. Just off the Byway you can MEYERS BEACH COUNTY PARKS INDIAN RESERVATION local specialty! visit two popular waterfalls: Siskiwit Falls and Lost Creek & COUNTY FOREST LANDS Falls. West of Cornucopia you will find the Lost Creek Bog HERMIT ISLAND Walk the Brownstone Trail along an old railroad grade or CORNUCOPIA State Natural Area. Lost Creek Bog forms an estuary at the take the Gil Larson Nature Trail (part of the Big Ravine Trail MICHIGAN ISLAND mouths of three small creeks (Lost Creek 1, 2, and 3) where System) which starts by a historic apple shed, continues RESERVATION LANDS they empty into Lake Superior at Siskiwit Bay. -

Beaufort Seas West To

71° 162° 160° 158° 72° U LEGEND 12N 42W Ch u $ North Slope Planning Area ckchi Sea Conservation System Unit (Offset for display) Pingasagruk (abandoned) WAINWRIGHT Atanik (Abandoned) Naval Arctic Research Laboratory USGS 250k Quad Boundaries U Point Barrow I c U Point Belcher 24N Township Boundaries y 72° Akeonik (Ruins) Icy Cape U 17W C 12N Browerville a Trans-Alaska Pipeline p 39W 22N Solivik Island e Akvat !. P Ikpilgok 20W Barrow Secondary Roads (unpaved) a Asiniak!. Point s MEADE RIVER s !. !. Plover Point !. Wainwright Point Franklin !. Brant Point !. Will Rogers and Wiley Post Memorial Whales1 U Point Collie Tolageak (Abandoned) 9N Point Marsh Emaiksoun Lake Kilmantavi (Abandoned) !. Kugrua BayEluksingiak Point Seahorse Islands Bowhead Whale, Major Adult Area (June-September) 42W Kasegaluk Lagoon West Twin TekegakrokLake Point ak Pass Sigeakruk Point uitk A Mitliktavik (Abandoned) Peard Bay l U Ikroavik Lake E Tapkaluk Islands k Wainwright Inlet o P U Bowhead Whale, Major Adult Area (May) l 12N k U i i e a n U re Avak Inlet Avak Point k 36W g C 16N 22N a o Karmuk Point Tutolivik n U Elson Lagoon t r !. u a White (Beluga) Whale, Major Adult Area (September) !. a !. 14N m 29W 17W t r 17N u W Nivat Point o g P 32W Av k a a Nokotlek Point !. 26W Nulavik l A s P v a a s Nalimiut Point k a k White (Beluga) Whale, Major Adult Area (May-September) MEADE RIVER p R s Pingorarok Hill BARROW U a Scott Point i s r Akunik Pass Kugachiak Creek v ve e i !. -

America Enters WWI on April 6, 1917 WW I Soldiers and Sailors

America enters WWI on April 6, 1917 WW I Soldiers and Sailors associated with Morris County, New Jersey By no means is this is a complete list of men and women from the Morris County area who served in World War I. It is a list of those known to date. If there are errors or omissions, we request that additions or corrections be sent to Jan Williams [email protected] This list provides names of people listed as enlisting in Morris County, some with no other connection known to the county at this time. This also list provides men and women buried in Morris County, some with no other connection known to the County at this time. Primary research was executed by Jan Williams, Cultural & Historic Resources Specialist for the Morris County Dept. of Planning & Public Works. THE LIST IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER WW I Soldiers and Sailors associated with Morris County, New Jersey Percy Joseph Alvarez Born February 23, 1896 in Jacksonville, Florida. United States Navy, enlisted at New York (date unknown.) Served as an Ensign aboard the U.S.S. Lenape ID-2700. Died February 5, 1939, buried Locust Hill Cemetery, Dover, Morris County, New Jersey. John Joseph Ambrose Born Morristown June 20, 1892. Last known residence Morristown; employed as a Chauffer. Enlisted July 1917 aged 25. Attached to the 4 MEC AS. Died February 27, 1951, buried Gate of Heaven Cemetery, East Hanover, New Jersey. Benjamin Harrison Anderson Born Washington Township, Morris County, February 17, 1889. Last known residence Netcong. Corporal 310th Infantry, 78th Division. -

Modeling Population Dynamics of Roseate Terns (Sterna Dougallii) In

Ecological Modelling 368 (2018) 298–311 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Modelling j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolmodel Modeling population dynamics of roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean a,b,c,∗ d e b Manuel García-Quismondo , Ian C.T. Nisbet , Carolyn Mostello , J. Michael Reed a Research Group on Natural Computing, University of Sevilla, ETS Ingeniería Informática, Av. Reina Mercedes, s/n, Sevilla 41012, Spain b Dept. of Biology, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155, USA c Darrin Fresh Water Institute, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 110 8th Street, 307 MRC, Troy, NY 12180, USA d I.C.T. Nisbet & Company, 150 Alder Lane, North Falmouth, MA 02556, USA e Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The endangered population of roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean consists Received 12 September 2017 of a network of large and small breeding colonies on islands. This type of fragmented population poses an Received in revised form 5 December 2017 exceptional opportunity to investigate dispersal, a mechanism that is fundamental in population dynam- Accepted 6 December 2017 ics and is crucial to understand the spatio-temporal and genetic structure of animal populations. Dispersal is difficult to study because it requires concurrent data compilation at multiple sites. Models of popula- Keywords: tion dynamics in birds that focus on dispersal and include a large number of breeding sites are rare in Roseate terns literature. -

Development and Efficacy Assessment of Equine Source Hyper-Immune Plasma Against Bacillus Anthracis

Development and Efficacy Assessment of Equine Source Hyper-Immune Plasma against Bacillus anthracis by James Marcus Caldwell A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama August 1, 2015 Keywords: horse, hyper immune plasma, Bacillus anthracis, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, toxin neutralization assay, experimental mouse B. anthracis challenge Copyright 2015 by James Marcus Caldwell Approved by Kenny Brock, Chair, Associate Dean of Biomedical Affairs Paul Walz, Professor of Pathobiology Sue Duran, Professor of Clinical Sciences Abstract The objective of the studies described here was to develop an equine source immune plasma against Bacillus anthracis and test its efficacy in two in vitro applications; as well as determine its capacity for passive protection in an infection model in mice. Initially, a safe and reliable immunization protocol for producing equine source hyper-immune plasma against B. anthracis was developed. Six Percheron horses were hyper-immunized with either the B. anthracis Sterne strain vaccine, recombinant protective antigen (rPA) homogenized with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant, or a combination of both vaccines. Multiple routes of immunization, dose (antigen mass) and immunizing antigens were explored for safety. A modified automated plasmapheresis process was then employed for the collection of plasma at a maximum target dose of up to 22 ml of plasma/kg of donor bodyweight to establish the proof-of- concept that large volumes of plasma could be safely collected from horses for large scale production of immune plasma. All three immunization protocols were found to be safe and repeatable in horses and three pheresis events were performed with the total collection of 168.36 L of plasma and a mean collection volume of 18.71 L (± 0.302 L) for each event. -

Boater's Guide

FULL SERVICE MARINA YAMAHA CERTIFIED TECHNICIANS GROTON, CT 50’ SLIPS AVAILABLE FOR 2019! (860) 445-9729 WINTER STORAGE • NEWLY DREDGED • FLOATING DOCKS www.PineIslandMarina.com MYSTIC, CT TRANSIENTS WELCOME! (860) 536-6647 SEASONAL DOCKAGE AVAILABLE FOR 2019 www.FortRachel.com • WINTER INDOOR & OUTDOOR STORAGE • FULL SERVICE BOAT YARD • POWER & SAIL • SHRINKWRAPPING • HAULING UP TO 70 TON & 20’ BEAM • WINTERIZATION CHESTER, CT (860) 526-1661 HEATED INDOOR BOAT STORAGE www.ChesterPointMarina.com RESERVE A SLIP INSTANTLY OUR FAMILY OF MARINAS ©2018 blp MARINE, LLC and All Subsidiary Logos. All Rights Reserved. 2 2019 Connecticut BOATERS GUIDE Take Us With You On the Water UNLIMITED TOWING MEMBERSHIP $159 Breakdowns happen all the time and the average cost of a tow is around $700. But with an Unlimited Towing Membership from TowBoatU.S., just show your card and your payment is made. With 600+ boats in 300+ ports, you’re never far from assistance when you need it. GET THE BOATU.S. APP FOR ONE TOUCH TOWING GO ONLINE NOW TO JOIN! BoatUS.com/Towing or 800-395-2628 Details of services provided can be found online at BoatUS.com/Agree or by calling. TowBoatU.S. is not a rescue service. In an emergency situation, you must contact the Coast Guard or a government agency immediately. 2019 Connecticut BOATER’S GUIDE A digest of boating laws and regulations Department of Energy & Environmental Protection State of Connecticut Boating Division Ned Lamont, Governor Michael Lambert, Bureau Chief Acting Boating Director Department of Energy & Environmental Protection ✦ ✦ ✦ Robert Klee, Commissioner Editor Susan Whalen, Deputy Commissioner COVER PHOTO: MARK CHANSKI Michael Lambert, Bureau Chief Mark Chanski Boating Resource Technician Sarah E is a single engine, 36’ Baltzer Voyageur. -

Breeding and Feeding Ecology of Bald Eagl~S in the Apostle Island National Lakeshore

BREEDING AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF BALD EAGL~S IN THE APOSTLE ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE by Karin Dana Kozie A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE College of Natural Resources UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin December 1986 APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE COMMITTEE OF; Dr. Raymond K. Anderson, Major Advisor Professor of Wildlife Dr. Neil F Professor of Dr. Byron Shaw Professor of Water Resorces ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people donated considerable time and effort to this project. I wish to thank Drs. Neil Payne and Byron Shaw -of-n my graduate ncommittee, for---providing Use fliT comments on this manuscript; my committee chairman, Dr. Ray Anderson, whose support, patience and knowledge will long be appreciated. Special thanks to Chuck Sindelar, eagle biologist for the state of Wisconsin, for conducting aerial surveys, organizing banding crews and providing a vast supply of knowledge and time, and to Ron Eckstein and Dave Evans of the banding crew, for their climbing expertise. I greatly appreciate the help of the following National Park Service personnel: Merryll Bailey, ecologist,.provided equipment, logistical arrangements and fisheries expertise; Maggie Ludwig graciously provided her home, assisted with fieldwork and helped coordinate project activities on the mainland while researchers were on the islands; park ranger/naturalists Brent McGinn, Erica Peterson, Neil Howk, Ellen Maurer and Carl and Nancy Loewecke donated their time and knowledge of the islands. Many people volunteered the~r time in fieldwork; including Jeff Rautio, Al Bath, Laura Stanley, John Foote, Sandy Okey, Linda Laack, Jack Massopust, Dave Ross, Joe Papp, Lori Mier, Kim Pemble and June Rado. -

Breeding Populations of Terns and Skimmers on Long Island Sound and Eastern Long Island: 1972-19751

1974-1977 No. 73 PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNA A SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Three Years Ending March 1977 Date of Issue: August 1977 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Members who participated in editing this issue of the Proceedings were: Berry Baker, Eugene Eisenmann, John Farrand, Jr., and Mary LeCroy. The Committee wishes to thank Alice Oliveri for typing manuscripts. Catherine Pessino, Editor Breeding Populations of Terns and Skimmers on Long Island Sound and Eastern Long Island: 1972-19751 DAVID DUFFY By 1972, it had become apparent to many working on colonial sea birds that the nesting terns and skimmers of Long Island were being increasingly exposed to a broad spectrum of pressures that might be causing severe changes in their populations. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB's) had been implicated in birth deformities of Common and Roseate Terns (Sterna hirundo and S. dougallii; Hays and Risebrough 1972). Mercury had been linked to feather loss in young terns (Gochfeld 1971). Egg shell thinning had been noted at several colonies in the area (Hays, pers. com.; pers. obs.); such thinning is believed to be caused by deriva tives of DDT (Wiemeyer and Porter 1970; Peakall 1970). Further pressure on tern populations had come from invasions of nesting sites by rats, development of recreational beaches, human harassment, and natural suc cession rendering colony sites unfit for nesting. For all of these factors there were only scattered and often anecdotal accounts of acute situations. What, if any, long-term effect there might be for the tern populations was unknown. Were Common and Roseate Terns holding their own? Or were they, instead, retreating to a few, safe colonies as their populations declined? Little as we knew of Commons and Rose ates, we knew even less of what was happening to Least Terns (Sterna albifrons) and Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger). -

NYS Takes Step to Protect Whales, Seals, and Sea Turtles Around Plum Island

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 18, 2019 Contact Laura McMillan, [email protected], 540-292-8429 NYS takes step to protect whales, seals, and sea turtles around Plum Island Southold, New York – In the span of just a few hours last Friday, the New York State Assembly and Senate unanimously passed legislation to improve protections for marine mammals and sea turtles in New York waters of eastern Long Island Sound. It also allows for the creation of a New York State bird conservation area. The Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Protection Area legislation establishes a protection area in New York State-owned waters around Plum, Great Gull, and Little Gull Islands that recognizes the zone as important for sea turtles, whales, porpoises, and seals; it is designed to not negatively impact fishing. The bill directs the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation to bring together the expertise of a broad range of organizations and individuals, including marine researchers, museums and academics, state agencies, and local governments. This advisory committee will be asked to consider how the archipelago and the waters surrounding it are interconnected, and then develop recommendations for protection measures. The bill, originally written and sponsored by Assemblyman Steve Englebright, has been proposed for several years. “This legislation will make the most of experts in marine life and birds, agency personnel and local officials, nonprofits, and others in considering the ecologically integrated relationship among Plum, Great Gull, and Little Gull Islands and the waters around them—and how to protect that area’s diverse and valuable marine resources, as well as traditional fishing activities,” said Louise Harrison, New York natural areas coordinator for Save the Sound. -

International Black-Legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents

ARCTIC COUNCIL Circumpolar Seabird Expert Group July 2020 International Black-legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 CAFF Designated Agencies: Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway Chapter 2: Ecology of the kittiwake ....................................................................................................................6 • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada Species information ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) Habitat requirements ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland Life cycle and reproduction ................................................................................................................................................................................7 • Icelandic Institute of Natural -

To Download Three Wonder Walks

Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) Featuring Walking Routes, Collections and Notes by Matthew Jensen Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) The High Line has proven that you can create a des- tination around the act of walking. The park provides a museum-like setting where plants and flowers are intensely celebrated. Walking on the High Line is part of a memorable adventure for so many visitors to New York City. It is not, however, a place where you can wander: you can go forward and back, enter and exit, sit and stand (off to the side). Almost everything within view is carefully planned and immaculately cultivated. The only exception to that rule is in the Western Rail Yards section, or “W.R.Y.” for short, where two stretch- es of “original” green remain steadfast holdouts. It is here—along rusty tracks running over rotting wooden railroad ties, braced by white marble riprap—where a persistent growth of naturally occurring flora can be found. Wild cherry, various types of apple, tiny junipers, bittersweet, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, mullein, Indian hemp, and dozens of wildflowers, grasses, and mosses have all made a home for them- selves. I believe they have squatters’ rights and should be allowed to stay. Their persistence created a green corridor out of an abandoned railway in the first place. I find the terrain intensely familiar and repre- sentative of the kinds of landscapes that can be found when wandering down footpaths that start where streets and sidewalks end. This guide presents three similarly wild landscapes at the beautiful fringes of New York City: places with big skies, ocean views, abun- dant nature, many footpaths, and colorful histories.