Air Freight for the United States William M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection Kristine L. Kaske; revised 2008 by Melissa A. N. Keiser 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Black and White Negatives....................................................................... 4 Series 2: Color Transparencies.............................................................................. 62 Series 3: Glass Plate Negatives............................................................................ 84 Series : Medium-Format Black-and-White and Color Film, circa 1950-1965.......... 93 -

B" [)Ennis Varks!) Librar"/A.Rchives [)Irect

EDITORIAL STAFF Publisher Tom Poberezny Vice-President, Marketing and Communications Dick Matt October 1992 Vol. 20, No. 10 Editor-in-Chief Jack Cox Editor CONTENTS Henry G. Frautschy Managing Editor 1 Straight & Level/ Golda Cox Espie "Butch" Joyce Art Director Mike Drucks Computer Graphic Specialists 2 AeroMaii Olivia l. Phillip Sara Hansen 3 AlC News/ Advertising compiled by H.G. Frautschy Mary Jones Associate Editor 5 Vintage Literature/Dennis Parks Page 9 Norm Petersen Feature Writers George Hardie, Jr. Dennis Parks 9 EAA Oshkosh '92-More Antiques Staff Photographers and Classics/H .G. Frautschy Jim Koepnick Mike Steineke Carl Schuppel Donna Bushman Editorial Assistant 13 Steve Pitcairn's Workhorse Mailwing/ Isabelle Wiske H .G. Frautschy EAA ANTIQUE/CLASSIC DIVISION, INC, 17 Custom Antique Champion OFFICERS President Vice-President Eicher's Monocoupe 90AL/ Espie "Butch" Joyce Arthur Morgan 604 Highway SI. 3744 North 51st Blvd. H.G. Frautschy Madison, NC 27025 Milwaukee, WI 53216 919/427-0216 414/442-3631 22 Pass It To Buck/ Secretary Treasurer Steven C. Nesse E.E. "Buck' Hilbert E.E. "Buck" Hilbert 2009 Highland Ave. P.O. Box 424 Albert Lea, MN 5(fJJ7 Union, IL 60180 flJ7/373-1674 815/923-4591 23 What Our Members Are Restoring/ Norm Petersen DIRECTORS John Berendt Robert C. "Bob' Brauer 7645 Echo Point Rd. 9345 S. Hoyne Cannon Falls, MN 55009 Chica~o.IL 26 Mystery Plane/George Hardie flJ7/263-2414 312/77 -21 05 Gene Chase John S. Copeland 2159 Carlton Rd. 28-3 Williamsbur8 Ct. 27 Calendar Oshkosh, WI 54904 Shrewsbury, MA 1545 414/231 -5002 508/842-7867 28 Welcome New Members Phil Coulson George Daubner 28415 Springbrook Dr. -

Aviation Trading Cards Collection

MS-519: Aviation Trading Cards Collection Collection Number: MS-519 Title: Aviation Trading Cards Collection Dates: Circa 1925-1940, 1996 Creator: Unknown Summary/Abstract: The collection consists of approximately 700 collectable trade cards and stamps issued by various industries, primarily the “cigarette cards” of tobacco manufacturers. The majority of the card or stamp series feature airplanes, but some series focus on famous aviators. Materials originate from the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany. Quantity/Physical Description: 0.5 linear feet Language(s): English, German Repository: Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, Wright State University, Dayton, OH 45435-0001, (937) 775-2092 Restrictions on Access: There are no restrictions on accessing material in this collection. Restrictions on Use: Copyright restrictions may apply. Unpublished manuscripts are protected by copyright. Permission to publish, quote, or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder. Preferred Citation: [Description of item, Date, Box #, Folder #], MS-519, Aviation Trading Cards Collection, Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio Acquisition: The collection was purchased by Special Collections and Archives from Cowan’s Auctions in Cincinnati, in December 2015. Other Finding Aid: The finding aid is available on the Special Collections & Archives, Wright State University Libraries website at: http://www.libraries.wright.edu/special/collectionguides/files/ms519.pdf. -

Plan Scale/Information Company/Drawn by Boeing F4B-4

Plan Scale/Information Company/Drawn By Boeing F4B-4 20” Wingspan No Scale Listed Model Aircraft Fokker D VI "Peanut Scale" Matt Mooney 1934 Caudron C.620 “Simoun” 1/40 Repla-Tech International/Bjorn Karlstrom Ryan S-C Kit # 552 1/24 Cleveland Models Ford Tri-Motor Model 5-AT 1/12 , 78" Wingspan, 52" Fuselage R/C Modeler Magazine Stinson Reliant 31" Wingspan No Scale Listed Mechanix Illustrated Curtiss Wright AT-9 No Scale , Has Actual Plane Dimensions Model Airplane News Waco Model D-6 1/64 W.A. Wylam New C-6 Waco 4-5 Place Cabin No Scale Listed W.A. Wylam Sidney Struhl's Ercoupe No Scale Listed, 21" Wing Span Allen Hunt Aeronca LB No Scale Listed, 23" Wing Span Allen Hunt 1935 Bellanca Aircruiser 66-70 ATC563 No Scale Listed, 30" Wing Span Joseph Kovel Stinson Senior Trainer No Scale Listed, 20" Wing Span Allen Hunt Earl Stahl's Fairchild 24R No Scale Listed, 29" Wing Span Allen Hunt Waco Cabin 1/8 , 52 1/4" Wing Span Berkeley Models 1939 Stinson SR-10 Reliant No Scale Listed, 10 1/2" Wing Span Repla-Tech International/Bjorn Karlstrom Fairchild F. 24 1/72 Repla-Tech International/Bjorn Karlstrom Fairchild KR21 No Scale Listed, 8 1/4" Wing Span Repla-Tech International/Bjorn Karlstrom Cessna T-50 Bobcat/Crane 1/48 Repla-Tech International/Bjorn Karlstrom 1929 Rearwin 2000C Ken-Royce No Scale Listed, 8 1/4" Wing Span Repla-Tech International/Bjorn Karlstrom Krier Great Lakes 10821-A 1/4 Not sure if both the A/B go together or are separate Model Builder Magazine/Larry Scott Krier Great Lakes 10821-B 1/4 Not sure if both the A/B go together -

Rubber Scale

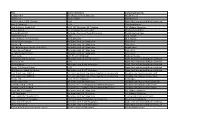

Rubber_Scale Number Name Identifier 560 Avro W.C. Hannan Avro Lancaster 1 Dennis O Norman B.A. Eagle Megow's Models B.A. Swallow No info NB-3 Barling Dick Gates 1910 Barnwell Monoplane Larry Kruse B.A.T. Baboon Matt Mooney BD-8 Walt Mooney Lincoln Beachey Monoplane Walt Mooney Pistachio Beardmore WeeBee Dave "VTO" Linstrum Pistachio Beardmore WeeBee Dave "VTO" Linstrum Beechcraft Bonanza Cleveland Model & Supply Co. 24" Beechcraft Lieut. B.P. Pond C17R Beechcraft Skymasters Corp. Beech Musketeer Walt Mooney C17B Beechcraft Cabin Plane Cleveland Model & Supply Company Inc. B-17L Beechcraft Popular Aviation Feb 1935 D-17 Beech No info B-17L Beechcraft Popular Aviotion Beech Staggerwing Flying Models Aug 1980 XFL-1 Bell Airabonita Walt Mooney XFL-1 Bell Airabonita Walt Mooney P-39 Bell Airacobra Model Builder Dec 1988 P-39 Bell Airacobra MAN Jun 1941 P-63 Bell King Cobra Whitman Publishing Co. Bellanca Aircruiser Joseph Kovel Bellanca Aircruiser Popular Aviation May 1934 Bellanca Aircruiser MAN Jul 1937 C-27A Bellanca Aircruiser Golden Age Reproductions Columbia Golden Age Reproductions B-25 Mitchell Model Builder Magazine ABC Robin A.B.C. Motors,Redbridge, Hampshire ABC Robin Aeromodeller ABC Robin Aeromodeller Jul 1946 Page 1 Rubber_Scale 101 Aero Walt Mooney,Model Builder, Sep 1976 C-3 Aeronca Unidentified Aeronca-Champion Model Airplane News, Jan 1959 Aeronca-Champion Ace Whittman Aeronca Chief Bill Schmidt, FM Dec 99 Aeronca 7AC Champion Dick Hawes FAC ? Aeronca Chief 54" Comet Pond Reproduction Aeronca K Comet (Seaplane) Comet Model Airplane & Supply Co. Aeronca K Unidentified Aeronca K Kit Number D-5 Aeronca K Rolfe Gregory Aeronca K (Seaplane) Kit No E-25, Comet Model Hobbycraft Inc. -

44Th Annual Report Contents

Calendar Year 2016 44th Annual Report Contents Chair’s Report ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 President’s Report ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Capital and Endowment Campaign Cabinet ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Curator & Executive Director Emeritus’ Report .................................................................................................................... 5 Royal Visit ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Noteworthy Events ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 2016 Financial Highlights ................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Fundraising .................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Journal of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society List of Journal Articles Updated 11-25-09

Journal of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society List of Journal Articles Updated 11-25-09 Key: “1+1” is Volume & Issue Number, in this case Volume #1, Issue #1. Add 62 to convert the Volume number into the Year. In this case, 63 (62 plus 1) is 1963. Issues are “1” (Spring), “2” (Summer), “3” (Fall) and “4” (Winter). “[4]” is the Page Number on which the article begins. The article title appears next followed by the author’s name. A more detailed Index of article content is not currently available. 1+1 [4] The First Canadian Aerial Victory * H. Creagen 1+1 [5] Front Cover Story: Vickers Viking * W. Wheeler 1+1 [6] Air Show * J. Burch 1+1 [8] Maybe She Would, Maybe She Wouldn't (Part 1) * W. Wheeler 1+2 [5] The Epic Flight of the R.34 * J. Forteath 1+2 [13] A "Piggy-Back" Landing * C. Catalano 1+2 [16] The Mystery of Billy Bishop's Missing Medal * H. Creagen 1+2 [17] The Search for Canadian Aces of World War One * H. Creagen 1+2 [19] Front Cover Story: Ju 52/1m * W. Wheeler 1+2 [20] G/C Henry John Burden, DSO, DFC * H. Creagen 1+2 [23] Maybe She Would, Maybe She Wouldn't (Part 2) * W. Wheeler 1+2 [25] Concerning McElroy, Ball and Richthofen * D. Oliver 1+2 [29] Canadian Museum Aircraft * K.M. Molson 1+3 [32] Front Cover Story: Armstrong-Whitworth Siskin IIIa * F. Taylor 1+3 [34] National Air Force Day 1963 * T.R. Waddington 1+3 [36] Ace Without Medals - P/O J.E.P. -

Giuseppe M. Bellanca Collection

Giuseppe M. Bellanca Collection David Schwartz 2000 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 6 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 6 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 7 Series 1: Mr. Bellanca's Professional Life, 1922-1960............................................. 7 Series 2: Technical Data, 1915-1958, undated...................................................... 41 Series 3: Personal Papers, 1908-1993.................................................................. 97 Series 4: Photographs, undated........................................................................... 119 Series 5: Miscellaneous and Oversize -

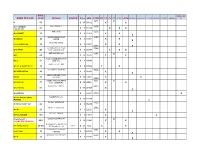

NAME of PLAN SPAN DETAILS SOURCE Price AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS RUBBER ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW ENGINE OT 16F1 X B 53 $ 15 35542 X X

WING REDUCED NAME OF PLAN SPAN DETAILS SOURCE Price AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS RUBBER ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW ENGINE OT 16F1 X B 53 $ 15 35542 X X B A 6 SWEDISH WALT MOONEY 84G6 $ 7 31412 LIGHTPLANE 21 X X X AER O KITS 14D5 B A CYGNET 15 $ 4 21303 X X X AEROMODELLER PLAN 14D5 B A EAGLE 20 MARSH $ 3 21301 X X X NEO DIME SCALE B A T MONOPLANE 16 $ 3 33564 X X 69E6 X AEROMODELLER PLAN 55A6 B Ae HAWK 20 11/83, BURKINSHAW $ 4 26314 X X X ALEX BARTER 1938 63B5 X B B 64 $ 15 28526 X X FLUG & MODELE TECHNIK B E 2 31 JUNE 1983 $ 8 15683 MODEL FLYER, 3/05 B E 2 C & ALBATROS C 1 15 $ 5 50506 X X BY BARNABY WAINFAN 95C6 B F INTERCEPTOR 10 $ 4 35916 X X AEROMODELLER PLANS B G 44 66 1/53 GUNIC $ 14 33660 X X 74G3 MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 8D3 X B G SPECIAL 77 12/38, GADEBURG $ 15 20551 X X STUART G BENNETT 68C4 B G SPECIAL 36 $ 10 29109 X X B G SPECIAL $ - 34617 RD41 X B H T 1 BEAUTY (WING MODELFLYG 2/98 $ 10 16819 MISSING) X BY ROY MARQUART 11C2 B INDOOR FUSELAGE 26 $ 8 35438 BOYS LIFE MAGAZINE 27F2 B L M 5 21 $ 4 22821 X X BY CARL RAMBO B POLLY GLIDER 16.5 $ 3 10950 X X B SKYROCKET ( LEON SHULMAN PLAN X $ 19 11992 INCOMPLETE RIB DETAIL) 49.5 X X Reminder-Scale sportster for B T Vintage Trainer: 47-3/4 .20 (Two plan sheets). -

Vintage Aircraft Plans List

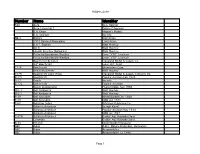

Aircraft Name Model By Pg. No. Post No. Span (inch) 1 - 1 Master Plan Index Link - 1 1 1 - Air Age Gas Models book scan 164 2449 Help file 1 - Colin Usher old Model Mag Link 143 2139 Help file 1 - Combat Models Ref. article 141 2104 Help file 1 - Cover art for Mushroom Model 210 3154 1 - COVERING W/ TISSUE - ADD ON Sundancer 192 2880 Help file 1 - COVERING WITH TISSUE Planeman 192 2873 Help file 1 - Covering with Tissue Word Doc.& PDF Planeman 192 2879 1 - Download Manager Link Free 201 3004 Help file 1 - Harold Towner list of plans 167 2498 Help file 1 - help file Advanced pdf passwd recovry 104 1552 Help file 1 - How-to Flight Trim Jim Kirkland 201 3011 1 - Image - tricks of the trade Planeman 199 2974 Help file 1 - International Model Airplane Coop link 192 2874 Help file 1 - link to Aerofred - plans,pdf etc 160 2397 1 - Link to colin usher mag.index 190 2837 Help file 1 - Link to free PDF converter 198 2966 Help file 1 - Link to Gimp book (how to) 185 2764 Help file 1 - Link to Gimp Tutorials 185 2767 Help file 1 - Link to Gimpshop (feels like photoshp) 184 2755 Help file 1 - link to Globe Swift Plans CAD Earl Stahl 51 753 38 1 - link to golden age 157 2346 Help file 1 - link to irfanview 154 2308 Help file 1 - link to Keith Laumer Plans Dave Fritzke 111 1656 1 - Link to Kits and Plans Welli & Lancas 223 3334 1 - Link to PDF Converter 207 3097 Help file 1 - Link to Plans & 3-views 235 3523 1 - Link to Plans Avro Lancaster Aeromodeller 223 3331 1 - link to Plans French website 164 2447 1 - Link to Rcgroup control line plans 222 3321 1 - link to Republic P-47 31inch. -

Bill Gordon Fonds, 96/16 (Yukon Archives Caption List)

Bill Gordon fonds acc# 96/16 YUKON ARCHIVES PHOTO CAPTION LIST Information taken from the photograph albums on loan to Yukon Archives from Bill Gordon, a former employee of White Pass and Yukon Route. Aviation comments in round brackets provided by Murray Biggin, Bob Cameron and Heather Jones (aviation enthusiasts). There is also information from Bob Cameron added in 2003. Other square bracketed information is added by Archivist. Photographs #1 - #35 are from one album, photographs #36 - #168 are from a second album. #1-#90 in PHO 443, #91-#169 in PHO 444. Further details about these photographs are available in the Yukon Archives Descriptive Database at www.yukonarchives.ca PHO 443 YA# Description: 96/16 #1 Trip to Livingstone Creek made with FORD CF-AZB with some miners and a load of supplies The FORD on the Livingstone Creek Landing Field. [additional info from Bob Cameron 2003: BYN Co. Ford Trimotor CF-AZB] 96/16 #2 Arrival of Bellaca [sic] from factory Bellanca - CF BLT (ca. 1939) [additional info from Bob Cameron 2003: BYN Co. Bellanca Aircruiser CF-BLT at the Whitehorse Airport. 1939-40] 96/16 #3 Inspection Bellanca - CF BLT [additional info from Bob Cameron 2003: BYN Co. Bellanca Aircruiser CF-BLT at the Whitehorse Airport. 1939-40] 96/16 #4 Changed over to skiis. Bellanca - CF BLT [additional info from Bob Cameron 2003: BYN Co. Bellanca Aircruiser CF-BLT at the Whitehorse Airport. 1939-40] 96/16 #5 XJ at Old Crow CF AXJ at Old Crow (Fokker Universal) [additional info from Bob Cameron 2003: BYN Co. -

Förteckning Arkiv-Ritningar (2020 – 11 - 01)

FÖRTECKNING ARKIV-RITNINGAR (2020 – 11 - 01) Enligt beslut vid SMOS’s årsmöte i september 2017 får medlemmarna mot enbart portokostnaden beställa ritningar från Arkivet så länge lagret räcker. Detta gäller dock endast dubbletter av ritningar, som redan ingår i Ritningsbanken samt SMFF-ritningar. Övriga ritningar utlånas gärna för kopiering. Arkivet finns i Halmstad och beställningar skickas till Sten Persson, tfn 035-104943, e-post [email protected] BYGGSATSRITNINGAR I ORIGINAL (vikta): UTLÄNDSKA Berkeley Astro Hog (RC spv. 183 cm) Berkeley D.H. Beaver ( F/F, C/L eller RC. Spv. 122 cm) Berkeley Payloader (45,5 cm g-modell) Comet Trainer Glider (spv. 29 cm) Comet Gull II (76 cm g-modell 1963) Come Cadet (37 cm g-modell 1964) Comet R.O.G. (46 cm g-modell 1964) Comet Cloud Buster (gummi/sport 1964) Flyline Curtiss Robin (0,8 cc spv. 104 cm) Hegi Telstar 2 (multi-RC) Honey Bee (inomhus g-modell) Jetco The Lark (gummi/sport, spv. 71 cm) Jetco Thermic ‘B’ ( kastglidare, spv. 51 cm) Keil Kraft: Halo ( 0,5 – 1,5 cc F/F) Keil Kraft Competitor (82 cm g-modell 1946) Keil Kraft Fokker D.VIII (51 cm g-modell) Mercury: D.H. 82 Tiger Moth (F/F skala) Scientific Sky-Master (91,5 cm g-modell) SIG Pigeon (HLG) SIG Cabinair ( gummi/sport, spv. 54 cm 1972) SIG Twenty-Niner (d:o, spv. 52 cm 1972) SIG Customaire (d:o, spv. 51 cm 1974) SIG Mini-Maxer (d:o, spv. 58,5 cm 1974) SIG Tiger (d:o, spv. 54,5 cm) Sky Skooter (Veron RC – risig!) Veron Focke-Wulf FW-190 ( linflygskala, spv.