Rutkow Excerpt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trashing Our Treasures

Trashing our Treasures: Congressional Assault on the Best of America 2 Trashing our Treasures: Congressional Assault on the Best of America Kate Dylewsky and Nancy Pyne Environment America July 2012 3 Acknowledgments: Contents: The authors would like to thank Anna Aurilio for her guidance in this project. Introduction…………………………….……………….…...….. 5 Also thank you to Mary Rafferty, Ruth Musgrave, and Bentley Johnson for their support. California: 10 What’s at Stake………….…..……………………………..……. 11 Photographs in this report come from a variety of public domain and creative Legislative Threats……..………..………………..………..…. 13 commons sources, including contributors to Wikipedia and Flickr. Colorado: 14 What’s at Stake……..………..……………………..……..…… 15 Legislative Threats………………..………………………..…. 17 Minnesota: 18 What’s at Stake……………..………...……………….….……. 19 Legislative Threats……………..…………………...……..…. 20 Montana: 22 What’s at Stake………………..…………………….…….…... 23 Legislative Threats………………..………………...……..…. 24 Nevada: 26 What’s at Stake…………………..………………..……….…… 27 Legislative Threats…..……………..………………….…..…. 28 New Mexico: What’s at Stake…………..…………………….…………..…... 30 Legislative Threats………………………….....…………...…. 33 Oregon: 34 What’s at Stake………………....……………..…..……..……. 35 Legislative Threats………….……..……………..………..…. 37 Pennsylvania: 38 What’s at Stake………...…………..……………….…………. 39 Legislative Threats………....…….…………….…………..… 41 Virginia: 42 What’s at Stake………………...…………...…………….……. 43 Legislative Threats………..……………………..………...…. 45 Conclusion……………………….……………………………..… 46 References…………………..……………….………………….. -

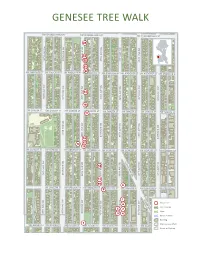

Genesee Tree Walk

S S S W W W S W G A D E N A A N D K L E O O A S V S T E A K E E R A S S T T S S S T T W S S 50TH AVE SW 50TH AVE S S SW S W 50TH AVE W W SW 50TH AVE SW C W W H O A G A A D N R E R L A E N D L G A K G E E S O O S O S K V T T E A N A E O E R S W S S S E T T T S T N T S S S S T S 4 9TH AVE SW S N 49TH AVE SW 49TH AVE SW 49TH AVE SW W 49TH AVE SW W W W W A O G A D N L E R A D A N E K E S O G E O K S V O T A E ! A E ! N 1 E R S S S 4 T S S T S T T S T ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 ! ! ! ! 1 1 ! S ! 1 ! E ! 2 ! ! ! 2 S S ! S 1 2 S ! 2 3 1 W ! 48TH AVE S 48TH AVE SW 48TH AVE SW C W 48TH AVE SW 5 48TH AVE S W W 6 ! W 2 3 W ! 4 W 8 2 1 1 9 H 0 7 A A G O A D N E R E R L A D L A N E K E O S G E O S K S V O T T A E A E O N E R S W T S ! ! ! ! S ! ! T S 1 1 1 T S T T N T 0 1 2 ! S ! S S S T R S 47TH AVE S W S 9 47 TH AVE SW 47TH AVE S W W W W 47TH AVE SW 47TH AVE SW W W A G O A D N E R L A E N D A E K G E O S O S K O V T E A E N A E E R S ! ! ! ! S S S T 5 3 S T T T T ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S S ! S ! ! S 46TH AVE SW 46TH AVE SW7 46 S TH AV W W E 4 SW W 46TH AVE SW 2 8 46TH AVE SW 6 W W W G L E A G O N A D N N E R L W A N D E A A Y K G E S O S W O S K O V T A E A E N A E R S S S S T S T T T S T W L S S S S S C 45TH AVE SW 45TH AVE SW 45TH AVE SW W W 45TH AVE SW W 45TH AVE SW W W H G K L A A E G O A N D N R N E R L W A L D N A E A E Y K O E G S S S O W S K V O T T E O A E A N E R W S S ! S S ! T S T T T N T S S T S S S W S I B W L T F S 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW W m W a r o t W u W e r a w c p i e e A l t u G d e O n e e D A s N C r i t r E n R v A a T L D o F g N i E n r A o e K r e O o G E u a O S P e p s S t V K O a u T y S E r E A A r N k u E e R i r S n S f S S a S T g T T T c T e 1 Trees for Seattle, a program of the City of Seattle, is dedicated to growing and maintaining healthy, awe- inspiring trees in Seattle. -

Download PDF

How to See into the Past Look up at the night sky The light you see emerged many years, even millennia, ago and has just traveled close enough to Earth to be visible with the naked eye or a telescope. The nearest optical supernova in two decades, SN 2014J was discovered on January 21, 2014. SN 2014J occurred in the Cigar Galaxy and lies about 12 million light-years away. When this blast oc- curred, geologically speaking Earth was in the Miocene Epoch. Count the rings on a tree Dendrochronology is the study of growth rings, which scientists can use to date temperate zone trees. In contrast, tropical trees lack the dramat- ic seasonal changes that produces periods of rapid growth and dor- mancy that result in growth rings. In 1964 Donald Currey, a graduate student in the geography department at the University of North Caro- lina, unintentionally cut down the oldest living organism on the planet. In what became known as the “Prometheus Story,” Currey’s core sample tool became lodged in bristlecone pine and the park officials advised him to simply cut down the tree, rather than lose the tool and waste this research opportunity. The tree Currey cut down became known as Prometheus, which was estimated to be 4,900 years old. Currently the old- est known living tree, about 4,600 years old, is in the White Mountains of California; there are likely even older bristlecones that have not been dated. Look at the desert landscape Movement and changes in the earth’s geology are apparent in the striated layers of rock and dirt, especially visible in the desert’s barren landscape. -

Germination and Early Survival of Great Basin Bristlecone Pine and Limber Pine

Plant Soil (2020) 457:167–183 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04732-9 REGULAR ARTICLE Mechanisms of species range shift: germination and early survival of Great Basin bristlecone pine and limber pine Brian V. Smithers & Malcolm P. North Received: 16 January 2020 /Accepted: 1 October 2020 /Published online: 8 October 2020 # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 Abstract showed weak negative responses while bristlecone pine Aims To examine the potential mechanistic predictors of germination and survival showed stronger negative re- germination and first-year survival in two species of Great sponses to temperature. Basin sub-alpine trees along an elevation gradient on three Conclusions Young trees are more sensitive to water soil types. limitation than to temperature and soil type has a strong Methods Using a network of experimental gardens, we moderating effect on water availability. Precipitation sowed limber pine and Great Basin bristlecone pine timing affected this availability with winter snowpack along elevational gradients at three sites on three differ- being less important in establishment than summer ent soil types. We collected germination and first-year monsoonal rain. These results point to the importance survival data of each species while measuring tempera- of substrate and understanding limitations on all life ture, soil water content, and other environmental vari- stages when attempting to predict species range shifts. ables to examine the potential predictors of first-year survival in these two species. Keywords Pinus longaeva . Pinus flexilis . Results Thanks to consecutive anomalously wet and dry Recruitment . Sub-alpine forest . Treeline . Great Basin years, we found germination and first-year survival to be largely limited by soil type, soil water content, and precip- Abbreviations itation timing. -

NWRRI Spring 2017 Newsletter

NWRRI - Desert Research Institute April 3, 2017 Volume 3, Issue 3 Newsletter written and compiled by Nicole Damon Director’s Letter We have wrapped up another Inside this issue: year at Nevada Water News and I’m very impressed by the unique and varied projects that our researchers Director’s Letter 1 have undertaken. From evaluating the presence of emerging contaminates in Lake Mead, to Project Spotlight 2 assessing urban water use, to analyzing groundwater basins and paleo-hydroclimatic data, these Events List 4 projects are exploring innovative solutions to conserve Nevada’s PI Spotlight 5 valuable water resources. I’m also proud that these projects have provided hands-on research Postdoc Interview 6 opportunities for a variety of students to learn skills that will prepare them for careers in the field of water resources research. at several treatment stages in a greenhouse environment to evaluate The newly funded NWRRI the transport, persistence, and project “Wastewater Reuse and accumulation of emerging RFPs Uptake of Emerging Contaminants contaminants in edible plants. by Plants” led by Drs. Kumud In addition to the exceptional If you have questions Acharya and Daniel Gerrity research that DRI faculty are about submitting a continues this innovative research. This project will evaluate the use of conducting, DRI also supports NWRRI proposal, advancements in water resources e-mail Amy Russell reclaimed water for agricultural irrigation. The benefit of using management and conservation ([email protected]). reclaimed water for agricultural statewide by partnering with For current RFP irrigation is that it could help programs such as WaterStart. information, visit the conserve valuable drinking water WaterStart is a public-private, not- for-profit, joint venture that works NWRRI website supplies. -

To Download the 2018 Inyo County

VISITOR’S GUIDE TO IINNYYOOCCOOUUNNTTYY 11 TH EDITION www.TheOtherSideOfCalifornia.com Table of Contents Chamber of Commerce of Inyo County Birds Come Back to Owens Lake Page 4 Bishop Chamber of Commerce & Borax Wagons Find A New Home Page 6 Visitor Center 690 N. Main St. Bishop, CA 93514 Enchanting Fall Colors Page 8 760-873-8405 1-888-395-3952 760-873-6999 Enjoy Bishop’s Big Backyard Page 10 [email protected] www.bishopvisitor.com Appealing Adventures in Lone Pine Page 11 Death Valley Chamber of Commerce 118 Highway 127 Everyone Loves A Parade Page 12 P.O. Box 157 Shoshone, CA 92384 760-852-4524 Historic Independence Page 14 760-852-4144 www.deathvalleychamber.org Direct Results Media, Inc. Direct ResultsLone Media, Pine Inc. Big Pine: An Adventure Hub Page 15 Chamber of Commerce 124 Main St BusinessPO B oCardsx 749 Inyo County Fun Facts Page 16 Lone Pine, CA 93545 Rodney Preul Ph: 760-876-4444 Fx: 760-876-9205 Sales Associate Owens River Links LA And Inyo Page 17 [email protected] https://w3.5x2ww.lonepinechamber.org Inyo Attractions At A Glance Page 19 6000 Bel Aire Way Cell: 760-382-1640 Bakersfield, CA 93301 [email protected] The 2018 Inyo County Visitor Guide is produced by the Lone Pine Chamber of Government Agencies: Commerce and the County of Inyo. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) contents do not necessarily reflect the views 760-872-4881 of the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce or the County of Inyo. (Except for our view that Inyo County is a spectacular place to visit. -

Exam 3 Study Guide

BIOL 462 Dendrology Study Guide, Exam 3 Plant Anatomy & Physiology: 1. What are the functions of the stem, leaves, and roots (i.e., support, transport, storage, photosynthesis, transpiration, anchorage, absorption)? 2. Describe the light and dark reactions of photosynthesis and how these enable plants to fix carbon into sugar. 3. What is the function of the chloroplast? Where is it located? 4. What are stomata, guard cells, and pores? What is their role in photosynthesis? How do they affect carbon dioxide and water in the plant? 5. Define transpiration, and explain how it affects temperature control and water movement in plants. 6. Define the following terms—be sure to indicate where they are located within a plant stem: xylem, vessels, tracheids, sapwood, heartwood, vascular cambium, phloem, sieve cells, and companion cells. 7. Do the following statements refer to xylem, phloem, or both? • fluid-conducting cells are dead at maturity. • fluid-conducting cells are alive at maturity. • created by vascular cambium. • located on outer region of stem. • located on central region of stem. • present in leaf veins. • present in vascular cylinder of roots. • hollow tube lacking cell walls or membranes. • rigid cell walls. • flexible cell walls. • fluid movement driven by transpiration. • fluid movement driven by diffusion from source to sink. • can be used to build houses and other wooden structures. 8. Compare and contrast sapwood and heartwood. Where is water transported? Where is waste stored? Which provides color to wood? Which is denser? Which is more resistant to decay? Which is composed of xylem? Which is dead? 9. Compare and contrast lateral roots, taproots, and root hairs. -

The Amazing Bristlecone Pine Trees!

And now . G-4 DOING SCIENCE with TREE-RINGS: The Amazing Bristlecone Pine Trees! For G-4 turn to pp 125 – 128 in the CLASS NOTES APPENDIX OK, so we extract the tree-ring cores with an increment borer . THEN WHAT? We compare one core to another and MATCH THE PATTERNS by lining up the rings of the really stressful years. To do this we use a special kind of graph . INTRODUCING: THE SKELETON PLOT! = a graph-paper plot of the tree’s most stressful years plotted for a sampled core: = The LONGEST LINES represent the most NARROW RINGS in the core! (only the narrow rings are plotted!) Any fledgling Dendrochronologists in the class? IF YOU WANT TO LEARN HOW to SKELETON PLOT . see pp 123 -124 in CLASS NOTES (this is NOT a course assignment – it’s just included for fun!) Pattern Matching: Narrow rings on skeleton plots can be MATCHED from one core to another: Skeleton Plot of Tree-Core A-3 A-1 Skeleton Plot of Plot of Tree-Core A-1 Multiple skeleton plots can then be combined to make a COMPOSITE PLOT of all cores from a site: By doing this we can make a MASTER SKELETON PLOT for a site or region and add calendar dates Site composites that have DATES assigned are referred to as “MASTERS” Skeleton Plot “Master” for a site (dates are marked & narrowest rings are indicated by long lines) On a MASTER we know the ACTUAL CALENDAR DATES for all the years with really narrow rings In today’s assignment you will work with Skeleton Plot Masters A site or region’s Master Skeleton Plot is used to assign dates to newly collected and undated tree-ring samples Skeleton Plot of undated core Master Chronology Skeleton Plot Today you will also work with another kind of graph: a TREE-RING WIDTH PLOT . -

Ancient Trees Great Basin Bristlecone Pines

National Park Service Great Basin U.S. Department of the Interior Great Basin National Park Ancient Trees Great Basin Bristlecone Pines Near the mountaintops of the Great Basin, you will find the world’s oldest living trees, the Great Basin bristlecone pine, Pinus longaeva. This remarkable tree ekes out a living in the most adverse conditions, growing at the same pace as the mountains over its four to five thousand year lifespan. Take the 1.5 mile walk (3 miles round trip) to the grove of ancient trees in the shadow of Wheeler Peak and experience the beauty of this tree that survives against the odds. The Oldest Trees Great Basin bristlecone pines grow near treeline In the White Mountains of California there is a (10,000 - 11,000 feet) in three groves in Great Basin bristlecone pine that has been dated at 4,600 years National Park. These trees are remarkable for their old, making it the oldest known living tree on great age and their ability to survive adverse Earth. A bristlecone pine near Wheeler Peak was growing conditions such as freezing temperatures, dated to be more than 4,900 years old in 1964. harsh winds, and a brief growing season. Unfortunately, before the area became a national park, the tree, now fondly known as Prometheus, Adaptations that promote the tree’s longevity was cut down and sectioned to obtain an accurate include needles that live up to 40 years and reading of its growth rings. A cross-section of dense, resinous wood that protects the tree from this tree can be seen at the park visitor center. -

Collapsing the Long Bristlecone Pine Tree Ring Chronologies

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 491-504 Article 35 2003 Collapsing the Long Bristlecone Pine Tree Ring Chronologies John Woodmorappe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Woodmorappe, John (2003) "Collapsing the Long Bristlecone Pine Tree Ring Chronologies," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 35. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/35 COLLAPSING THE LONG BRISTLECONE PINE TREE RING CHRONOLOGIES JOHN WOODMORAPPE, MA, BA 6505 N. NASHVILLE #301 CHICAGO, IL 60631, USA KEYWORDS: Biblical genealogies, dendrochronology, carbon 14 dating, post Flood, earth movements, landslides. ABSTRACT No obvious grounds exist for questioning the overall validity of the bristlecone pine (BCP) long chronologies, but there is “play” in some of the crossmatches, imposing an element of flexibility in the interpretation of the data. Not enough is known about processes leading to plural annual rings in BCP for further consideration. A new model, based on non-climatic “overprinting” of incipient tree rings in a time-transgressive manner, shows how less than 1,000 years of real time could have become inflated to over 4,000 years of apparent time. -

Caitlin Johnston Final Paper 12 June, 2008

Caitlin Johnston Final Paper 12 June, 2008 A comprehensive look at Bristlecone Pines, their setting and scientific uses ABSTRACT This paper examines the Bristlecone Pine (pinus longaeva), the longest-living, noncloning organism, and its importance to science. In order to better understand the region where the oldest bristlecones are found, the paper also discusses the geology and climate of the White Mountains. The White Mountains are located in the rainshadow of the Sierra Nevada in California. The dolomite outcrops, high alkaline content, and low precipitation (<12 cm/yr) are essential for the bristlecones. In addition the high altitude of 14,246 feet (4343m) is essential, since bristlecones grow best between 10,000 and 11,000 feet (3048 to 3354 m). Ed Schulman was the first to study bristlecones in depth. Bristlecones can live to be as old as 4,844-years-old, with several reaching ages of more than 3,000 to 4,000 years. Their ability to dieback onto the cambrium layer in addition to having highly resinous wood is essential to their longevity. Schulman’s research, along with A. E. Douglas, led to the development of dendrochronology. Crossdating, the process of matching growth patterns among several tree series, is the foundation of dendrochronology. Bristlecones are especially important for dendrochronology since their chronological records go back about 11,000 years. These records have helped correct radiocarbon dating, allowing scientists to accurately date items to the correct year. Knowledge of bristlecones is essential for gaining a better understanding of the historical geologic and climactic state of regions. 2 INTRODUCTION In the extreme conditions and high altitudes of the White-Inyo Mountains lives the world’s longest-living, noncloning organism: the Bristlecone Pine (pinus longaeva) (Petrides). -

Creationist Commentary on and Analysis of Tree-Ring Data: a Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 8 Article 45 2018 Creationist commentary on and analysis of tree- ring data: A review DOI: https://doi.org/10.15385/jpicc.2018.8.1.38 Roger W. Sanders Core Academy of Science Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Sanders, R.W. 2018. Creationist commentary on and analysis of tree-ring data: A review. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 516–524. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship. Sanders, R.W. 2018. Creationist commentary on and analysis of tree-ring data: A review. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 516–524. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship. CREATIONIST COMMENTARY ON AND ANALYSIS OF TREE-RING DATA: A REVIEW Roger W. Sanders, Core Academy of Science, PO Box 1076, Dayton, TN 37321 [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper 1) reviews the creationist literature concerning the use of tree growth rings in determining the ages of long- lived trees, developing post-Pleistocene chronologies, calibrating radiocarbon dates, and estimating past climates, and 2) suggests positive research directions using these data to develop creationist models of biblical earth history. Only a single author attempted to use tree-ring data to model pre-Flood climate zonation. However, most commentaries and studies focused on dendrochronology and using it to calibrate radiocarbon dates.