District Assemblies' Perspectives on the State of Planning I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CWB Msc Thesis

MSc Hydrogeology: Thesis University of Birmingham Rebecca Esther Carmel Simister URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT: USING THE CITY WATER BALANCE MODEL TO MODEL URBAN WATER SYSTEMS IN ACCRA, GHANA i Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an MSc in Hydrogeology in the School of Earth Sciences, University of Birmingham in September 2010. Student: Supervisor: ii ABSTRACT: The use of a scoping model to quantify the movement of water within urban water and waste water systems to the underlying aquifer has been applied to Accra, Ghana. Currently, only 55% of Accra has access to mains water, with water shortages and intermittent water connection to households becoming more common (AVRL 2010). In 2007 Accra became part of the SWITCH project as a demonstration city, which means that it promotes and undertakes on research into sustainable urban water systems. The City Water Balance (CWB) package has been developed by SWITCH to assess the impacts of future water management options in the city on recharge and the urban water cycle. The implementation of different water and waste water management options can be tested in the model to find more appropriate and sustainable water use improvements on a variety of spatial and temporal scales. A model has been successfully developed and calibrated, within the available limits, for the Accra Metropolitan Area that quantifies the inputs, processes and outputs of water within the urban water cycle. In this study, three different population scenarios for Accra in 2030 were tested along with five different water management options for present day city. The population scenarios showed that the imported water might reach up to three times the imported water volume at present, prompting the need for implementing more sustainable water practices in the future. -

Ghana Gazette

GHANA GAZETTE Published by Authority CONTENTS PAGE Facility with Long Term Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 1236 Facility with Provisional Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 201 Page | 1 HEALTH FACILITIES WITH LONG TERM LICENCE AS AT 12/01/2021 (ACCORDING TO THE HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND FACILITIES ACT 829, 2011) TYPE OF PRACTITIONER DATE OF DATE NO NAME OF FACILITY TYPE OF FACILITY LICENCE REGION TOWN DISTRICT IN-CHARGE ISSUE EXPIRY DR. THOMAS PRIMUS 1 A1 HOSPITAL PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI KUMASI KUMASI METROPOLITAN KPADENOU 19 June 2019 18 June 2022 PROF. JOSEPH WOAHEN 2 ACADEMY CLINIC LIMITED CLINIC LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE MAMPONG KUMASI METROPOLITAN ACHEAMPONG 05 October 2018 04 October 2021 MADAM PAULINA 3 ADAB SAB MATERNITY HOME MATERNITY HOME LONG TERM ASHANTI BOHYEN KUMASI METRO NTOW SAKYIBEA 04 April 2018 03 April 2021 DR. BEN BLAY OFOSU- 4 ADIEBEBA HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG-TERM ASHANTI ADIEBEBA KUMASI METROPOLITAN BARKO 07 August 2019 06 August 2022 5 ADOM MMROSO MATERNITY HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI BROFOYEDU-KENYASI KWABRE MR. FELIX ATANGA 23 August 2018 22 August 2021 DR. EMMANUEL 6 AFARI COMMUNITY HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI AFARI ATWIMA NWABIAGYA MENSAH OSEI 04 January 2019 03 January 2022 AFRICAN DIASPORA CLINIC & MATERNITY MADAM PATRICIA 7 HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI ABIREM NEWTOWN KWABRE DISTRICT IJEOMA OGU 08 March 2019 07 March 2022 DR. JAMES K. BARNIE- 8 AGA HEALTH FOUNDATION PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI OBUASI OBUASI MUNICIPAL ASENSO 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 DR. JOSEPH YAW 9 AGAPE MEDICAL CENTRE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI EJISU EJISU JUABEN MUNICIPAL MANU 15 March 2019 14 March 2022 10 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION -ASOKORE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE KUMASI METROPOLITAN 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION HOSPITAL- DR. -

Second CODEO Pre-Election Observation Report

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) CONTACT Secretariat: +233 (0) 244 350 266/ 0277 744 777 Email: [email protected]: Website: www.codeoghana.org SECOND PRE-ELECTION ENVIRONMENT OBSERVATION STATEMENT STATEMENT ON THE VOTER REGISTER Introduction The Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) is pleased to release its second pre- election observation report, which captures key observations of the pre-election environment during the month of October 2020, ahead of the December 7, 2020 presidential and parliamentary elections of Ghana. The report is based on weekly reports filed by 65 Long-Term Observers (LTOs) deployed across 65 selected constituencies throughout the country. The observers have been monitoring the general electoral and political environment including the activities of key election stakeholders such as the Electoral Commission (EC), the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE), political parties, the security agencies, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and religious and traditional leaders. Below are key findings from CODEO’s observation during the period. Summary of Findings: • Similar to CODEO’s observations in the month of September 2020, civic and voter education activities were generally low across the various constituencies. • There continues to be generally low visibility of election support activities by CSOs, particularly those aimed at peace promotion. • COVID-19 health and safety protocols were not adhered to during some political party activities. • The National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP) remain the most visible political parties in the constituencies observed as far as political and campaign- related activities are concerned. Main Findings Preparatory Activities by the Electoral Commission Observer reports showed intensified preparatory activities by the EC towards the December 7, 2020 elections. -

Ningo-Prampram Municipality

NINGO-PRAMPRAM MUNICIPALITY Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Ningo-Prampram Municipality is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Prevention of COVID-19 in Ghana: Compliance Audit of 7 Selected Transportation Stations in the Greater Accra Region 8 of Ghana

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20120196; this version posted June 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 2 3 4 5 6 Prevention of COVID-19 in Ghana: Compliance audit of 7 selected transportation stations in the Greater Accra region 8 of Ghana 9 Harriet Affran Bonful,1 Adolphina Addo-Lartey,1 Justice MK Aheto2, John Kuumouri Ganle3, 10 Bismark Sarfo1, Richmond Aryeetey3* 11 1. Department of Epidemiology and Disease Control, University of Ghana School of Public 12 Health 13 2. Department of Biostatistics, University of Ghana School of Public Health 14 3. Department of Population and Family Health, University of Ghana School of Public Health 15 16 17 18 19 * Corresponding Author 20 Email: [email protected] (RA) 21 22 23 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20120196; this version posted June 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 24 25 Abstract 26 Globally, as little evidence exists on transmission patterns of COVID-19, recommendations to 27 prevent infection include appropriate and frequent handwashing plus physical and social 28 distancing. -

Download File

March 2018 Study Report CHILD PROTECTION SECTION UNICEF Ghana Country Office March 2018 CHILD PROTECTION SECTION UNICEF Ghana Country Office Rapid Assessment on Child Protection related Attitude, Beliefs and Practices in Ghana @2018 March 2018 All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced, as a whole or in part, provided that acknowledgement of the sources in made. Notification of such would be appreciated. Published by: UNICEF Ghana For further information, contact: UNICEF Ghana P.O. Box AN 5051, Accra-North, Ghana. Telephone: +233302772524; www.unicef.org/ghana These document was put together by Research and Development Division of the Ghana Health Service on behalf of UNICEF Ghana with financial support from the Government of Canada provided through Global Affairs Canada. The contents of the this document are the sole responsibility of research team. The contents don’t necessarily reflect the views and positions of UNICEF Ghana and Global Affairs Canada. Contents Acknowledgements 12 Executive Summary 13 Key Findings 14 Demographic characteristics of respondents 14 Belief and attitudes about child protection issues 14 Practices related to child protection 16 Conclusion 16 Recommendations 17 1. Introduction 20 1.1 Objectives 20 2. Methodology 22 2.1 Study sites 22 2.2 Sampling Frame for section of Enumeration Areas (EAs) 22 2.3 Allocation of EAs 22 2.4 Selection of communities, houses and households 23 2.5 Selection of individual respondents 23 2. 6 Data Collection Procedure 24 2. 7 Data Management and Analysis 24 2.8 Ethical -

CODEO's Statement on the Official Results of The

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CODEO’S STATEMENT ON THE OFFICIAL RESULTS OF THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS CONTACT Mr. Albert Arhin CODEO National Coordinator Phone: +233 (0) 24 474 6791 / (0) 20 822 1068 Secretariat: +233 (0) 244 350 266/ 0277 744 777 Email: [email protected] Website: www.codeoghana.org Thursday, December 10, 2020 Accra, Ghana Introduction On Sunday, December 6, 2020, the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO), in its press statement, communicated to the nation its intention to once again employ the Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT) methodology to observe the 2020 presidential election, just as it did in 2008, 2012 and 2016. The PVT methodology is a reliable tool available to independent and non-partisan citizens’ election observer groups around the world for verifying the accuracy of official presidential elections results. In keeping with our protocols, which is that CODEO releases its PVT findings after the official results have been announced by the Electoral Commission, CODEO is here to release its PVT estimates for the presidential election. CODEO’s PVT estimates for the presidential results form part of its comprehensive election observation activities for the 2020 elections that covered voter registration exercise, pre-election environment observation for three months (September to November), and election day observation. The PVT Methodology The PVT is an advanced and scientific election observation technique that combines well-established statistical principles and Information Communication Technology (ICT) to observe elections. The PVT involves deploying trained accredited Observers to a nationally representative random sample of polling stations. On Election-Day, PVT Observers observe the entire polling process and transmit reports about the conduct of the polls and the official vote count in real-time to a central election observation database, using the Short Message Service (SMS) platform. -

Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change and Flooding in Accra

Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change and Flooding in Accra, Ghana A thesis presented to the faculty of the Voinovich School of Leadership & Public Affairs In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Audrey N. K. Komey August 2015 © 2015 Audrey N. K. Komey. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change and Flooding in Accra, Ghana by AUDREY N. K. KOMEY has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the Voinovich School of Leadership & Public Affairs by Elizabeth E. Wangui Assistant Professor of Geography Mark Weinberg Director, Voinovich School of Leadership & Public Affairs 3 ABSTRACT KOMEY, AUDREY N. K., M.S., August 2015, Environmental Studies Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change and Flooding in Accra, Ghana Director of Thesis: Elizabeth E. Wangui In the wake of climate change and flood severity in Ghana, the government of Ghana has developed a ten year adaptation strategy document (National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy) to assist institutions and stakeholders in addressing the impact of climate change in various sectors of the country. Institutional role has become necessary in tackling flood simply because the success of any adaptation strategies in part depend on the institutional arrangement in place and studies have been conducted to affirm this argument (Agrawal, McSweeney & Perrin, 2008; IPCC 2013). This thesis focuses on an analysis of the document and how it addresses flooding in the wake of climate change. Flooding forms a major disaster that the country as a whole faces annually but focus is on the Greater Accra region specifically the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA). -

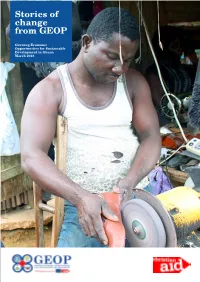

Stories of Change from GEOP

Stories of change from GEOP Growing Economic Opportunities for Sustainable Development in Ghana March 2018 Empowering people with disabilities to live dignified lives GEOP case studies On the left of the picture is Amina proudly displaying slippers she designed using beads, as a result of the training she received from the GEOP project. About GEOP Brief background bags made of bamboo sticks in order Kamgbunli is found in the Ellembelle to cater for her family. However, the Growing Economic Opportunities District of the Western Region of business collapsed because of the for Sustainable Development Ghana. The community is located a change in preference of her project (GEOP) is a three-year, EU- few miles from the Western coast of customers to foreign bags. funded project that aims to foster Ghana and it is situated in a hilly strong partnerships between civil area, a short distance from Ampain Participating in bead- society and local authorities, to and Eikwe communities. Peasant making training promote local job creation, revenue farming is predominantly the Amina was involved actively in the mobilisation and expansion of occupation of the people of needs assessment process and economic activities. Kamgbunli. selection of people with disabilities (PWDs) for the vocational skills The project is implemented in the Mrs Amina Issah Ebanyinle, a 42- training of the GEOP project. Ellembelle District, Western year-old woman lives with her Together with other PWDs who Region, and Ayawaso East and household in the Kamgbunli showed an interest in beads making, Ablekuma South sub-metros of the community. She is divorced and has the project trained Amina and her Accra Metropolitan Assembly, three children (two boys and a girl). -

STAR-Ghana Elections 2016 Grants Partners NO

STAR-Ghana Elections 2016 Grants Partners NO. NAME OF ORGANISATION PROJECT TITLE AND OUTCOME OFFICE ADDRESS REGION APPROVED BUDGET (GBP) OPEN COMPONENT Voter Education 1. Socioserve-Ghana (SSG) – Promoting Inclusiveness In Election 2016 Box 250, 1st , 2nd & 3rd Eastern 50,721.34 Asuogyaman E/R - Distric in Outcome: Free and fair participation of rural citizens in Floors, GCB Building , VR/ER Ghana's election 2016 Akosombo 2. Centre for Active Learning Peaceful and Credible Election (PeaCE) Project Plot No. 11 Agric-Ridge. Northern 50,443.18 and Integrated Development - Outcome: A peaceful, democratic and credible elections Agric-Ridge Road, CALID in Gushiegu, Nanumba through increased voting rights and youth confidence in the adjacent SWAD Fast North, Bunkpurgu/Yunyoo, registration and voting process in Gushiegu, Nanumba North, Food. and Yendi Districts Bunkpurgu/Yunyoo, and Yendi Districts 3. Trade Aid Integrated in 5 Enhanced Citizens Participation in election 2016 in five P.O. Box 713, Municipal Upper East 43,237.01 constituencies in the Upper constituencies in the Upper East Region Assembly, Bolgatanga, East Region Outcome: To contribute to peaceful, free and fair non-violent UE general election in 2016 which will enhance Ghana’s democracy and national cohesion for accelerated development. 4. Social Initiative for Literacy Maximizing voter turnout and Minimizing rejected votes: “ Social Initiative for Upper 54,046.26 and Development Program- The Mini-Max Voter Education 2016 Literacy and West SILDEP (Lead) and TEERE – UE Outcome: To increase voter turnout and reduce rejected Development Program, R and UW Regions votes in election 2016 P.O. Box 78, Tumu 5. -

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO)

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) CONTACT Secretariat: +233 (0) 244 350 266/ 0277 744 777 Email: [email protected]: Website: www.codeoghana.org THIRD PRE-ELECTION ENVIRONMENT OBSERVATION STATEMENT STATEMENT ON THE VOTER REGISTER Introduction The Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) is pleased to release its third pre-election observation report, which captures key observations of the pre-election environment during the month of November 2020, ahead of the December 7, 2020 presidential and parliamentary elections of Ghana. The report is based on weekly reports filed by 65 Long-Term Observers (LTOs) deployed across 65 selected constituencies throughout the country. The observers have been monitoring the general electoral and political environment including the activities of key election stakeholders such as the Electoral Commission (EC), the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE), political parties, the security agencies, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and religious and traditional leaders. Below are key findings from CODEO’s observation during the period. Summary of Findings: • Civic and voter education activities have been intensified by the NCCE and the EC across the observed constituencies. • COVID-19 health and safety protocols were not adhered to during some political party activities. • Education remains the main policy issue discussed at campaign activities by the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). Main Findings Preparatory Activities by State and Non-State Actors CODEO's Long Term Observer reports indicated a significant increase in the preparatory activities by the EC towards the conduct of the 2020 Presidential and Parliamentary elections. Specifically, CODEO's LTOs reported observing/hearing the Electoral Commission undertake various District IPAC meetings, recruitment and training of its election staff.