Historic Context by Nathalie Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

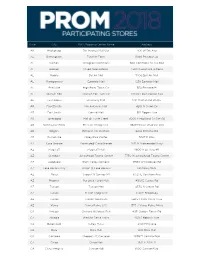

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

Mad River Station 2717 Miamisburg Centerville Road, Dayton, Ohio 45459

MAD RIVER STATION 2717 MIAMISBURG CENTERVILLE ROAD, DAYTON, OHIO 45459 Mad River Station benefits from its strong location at the intersection of State Route 725 and Mad River Road. The property is adjacent to the Dayton Mall, a 1.3 million square foot center anchored by DSW, Elder- Beerman, JCPenney, Macy’s, Old Navy and Sears. Mad River Station is in the Miami Township of Dayton, Ohio, and is part of the Dayton MSA. PROPERTY INFORMATION LEASING INFORMATION Type Community Shopping Center JOHN MCMAHON GLA 157,742 +/- SF [email protected] Parking 700 Spaces 914.288.3311 Anchors Office Depot, Pier 1 Imports, Barnes & Noble (not owned) 411 Theodore Fremd Ave Suite 300 Rye, NY 10580 MAD RIVER STATION 2717 MIAMISBURG CENTERVILLE ROAD, DAYTON, OHIO 45459 AVAILABLE SPACES LEASED SPACES NOT OWNED AMAR INDIAN RESTAURANT AVAILABLE AVAILABLE ZONE AVAILABLE 1 2 AVAILABLE EYE-MART 3 TENNIS AVAILABLE 4 AVAILABLE AVAILABLE 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AVAILABLE 17 15 18 MONUMENT SIGN AVAILABLE 13 14 MAD RIVER RD (Not Owned) PYLON 16 MIAMISBURG CENTERVILLE RD KEY TENANT ROSTER 1. Amar LEASEDIndian RestaurantAVAILABLE ............................. 6,696 sf 7. Tennis Zone ................................................. 3,014sf 13. Available ................................................. 10,111 sf 2. Available .....................................................N 1,512 sf 8. Available ..................................................... 3,922 sf 14. Starbucks ................................................. 2,289 sf 3. Available .................................................... -

WALGREENS 183 E Dayton Yellow Springs Road Fairborn, OH 45324 TABLE of CONTENTS

NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING WALGREENS 183 E Dayton Yellow Springs Road Fairborn, OH 45324 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Profile II. Location Overview III. Market & Tenant Overview Executive Summary Photographs Demographic Report Investment Highlights Aerial Market Overview Property Overview Site Plan Tenant Overview Map NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DISCLAIMER STATEMENT DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum is proprietary and strictly confidential. STATEMENT: It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from The Boulder Group and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of The Boulder Group. This Offering Memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. The Boulder Group has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation. The information contained in this Offering Memorandum has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, The Boulder Group has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has The Boulder Group conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE The Boulder Group is pleased to exclusively market for sale a single tenant net leased Walgreens property located SUMMARY: in Fairborn, Ohio. -

90 Years of Flight Test in the Miami Valley

in the MiamiValley History Offke Aeronautical Systems Center Air Force Materiel Command ii FOREWORD Less than one hundred years ago, Lord Kelvin, the most prominent scientist of his generation, remarked that he had not “the smallest molecule of faith’ in any form of flight other than ballooning. Within a decade of his damningly pessimistic statement, the Wright brothers were routinely puttering through the skies above Huffman Prairie, pirouetting about in their frail pusher biplanes. They were there because, unlike Kelvin, they saw opportunity, not difficulty, challenge, not impossibility. And they had met that challenge, seized that opportunity, by taking the work of their minds, transforming it by their hands, making a series of gliders and, then, finally, an actual airplane that they flew. Flight testing was the key to their success. The history of flight testing encompassesthe essential history of aviation itself. For as long as humanity has aspired to fly, men and women of courage have moved resolutely from intriguing concept to practical reality by testing the result of their work in actual flight. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, notable pioneers such asthe French Montgolfier brothers, the German Otto Lilienthal, and the American Octave Chanute blended careful study and theoretical speculation with the actual design, construction, and testing of flying vehicles. Flight testing reallycame ofage with the Wright bro!hers whocarefullycombined a thorough understanding of the problem and potentiality of flight with-for their time-sophisticated ground and flight-test methodolo- gies and equipment. After their success above the dunes at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17,1903, the brothers determined to refine their work and generate practical aircraft capable of routine operation. -

Miami Township Montgomery County, Ohio Strategic Plan

Miami Township Montgomery County, Ohio Strategic Plan Updated 2017 1 Table of Contents Mission Statement ………………………………………………………….3 Introduction of Miami Township.............................................................4 2017 Priorities of Miami Township Elected Officials ………….….……..7 Miami Township Parks ……………………………………….…….7 Miami Township Staffing ………………………………………......8 Branding and Public Image ………………………………………..8 Economic Development and Blighted/Aging Areas……….……..9 Communications …………….……………………………………..10 Infrastructure………………………………………………………...11 Administration Department ……………………………………………..…12 Community Development Department……………………………….…..15 Information Technology Department….................................................20 Compliance Department …...................................................................23 Finance Department ………………………………………….…………....26 Police Department ………………………………………………………….28 Public Works Department…………………………….…………………....31 Miami Valley Fire District…………………………………………………...35 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...36 2 Mission Statement Miami Township’s Mission is to provide excellent services to our residents and businesses, emphasizing integrity, efficiency and fiscal responsibility, positioning the township for future growth and continued success. 3 INTRODUCTION OF MIAMI TOWNSHIP Who We Are: Miami Township, Montgomery County, is the seventh largest township in the State of Ohio with an unincorporated population of 29,131. It is both rural and urban with the convenience of city life and the openness -

Dayton,OH Sightseeing National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Dayton,OH Sightseeing National Museum of the U.S. Air Force A “MUST SEE!” in Dayton, the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force is the world’s largest and oldest military aviation museum and Ohio’s most visited FREE tourist attraction with nearly 1.3 million annual visitors. This world-renowned museum features more than 360 aerospace vehicles and missiles and thousands of artifacts amid more than 17 acres of indoor exhibit space. Exhibits are arranged chronologically so it’s easy to visit the areas that interest you most. Examine a Wright Brothers plane, sit in a jet cockpit, walk through a NASA shuttle crew compartment trainer, or stand in awe of the world’s only permanent public display of a B-2 stealth bomber. Feeling adventurous? Check out the Morphis Movie Simulator Ride, a computer controlled simulator for the entire family. Capable of accommodating 12 passengers, the capsule rotates and gyrates on hydraulic lifts, giving the passengers the sensation of actually flying along. Dramamine may be required. Or, take in one of the multiple daily movies at the Air Force Museum Theatre’s new state-of-the-art D3D Cinema showing a wide range of films on a massive 80 foot by 60 foot screen. Satisfy your hunger at the Museum’s cafeteria (where you can even try out freeze-dried ‘astronaut ice cream!’), or shop for one-of-a-kind aviation gifts in the Museum’s impressive gift shop. And, just when you didn’t think it couldn’t happen, the best is getting even better! In 2016 a new fourth hangar will open. -

INTERNATIONAL PAPER COMPANY (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 _____________________________________________________ FORM 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012 or TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 1-3157 INTERNATIONAL PAPER COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) New York 13-0872805 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 6400 Poplar Avenue Memphis, Tennessee (Address of principal executive offices) 38197 (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (901) 419-7000 _____________________________________________________ Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $1 per share par value New York Stock Exchange _____________________________________________________ Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Download This PDF File

OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE BOOK REVIEWS 67 Younger brother Howard Jones, who also became a between the natural environment and the rich history medical doctor, enjoyed roaming the woods and fields of this special place. and supplied most of the nests and eggs that went into Huffman Prairie today is a 114-acre fragment the family “cabinet” and became the reference library for of its original area within the Wright-Patterson Air the drawings. Genevieve’s mother, Virginia, supported Force Base, a short distance east of Dayton, Ohio. In any project her daughter was involved with but had no 1986 the natural portion of the Huffman Prairie was personal interest in ornithology and natural history. designated as an Ohio Natural Landmark Area and in She also had no training as an artist. After Genevieve’s 1990, Huffman Prairie Flying Field was designated as death, Virginia’s love for her daughter and wishes to a National Historic Landmark. It is a component of honor her memory inspired her to join her husband the National Aviation Heritage Area. and son in the project. Virginia taught herself the The book weaves together several themes: an skills needed to draw on the lithographic stones and excellent history of the land even before the Wright how to color them. Genevieve’s friend, Eliza Shulze, brothers got involved, the brothers' work on drew additional plates and helped Virginia finish the developing and improving airplane design, and the coloring of plates. In all, Genevieve drew only five eventual development of Wright-Patterson Air Force plates, Eliza did ten plates, Howard drew eleven plates Base (which encompasses the Huffman Prairie). -

2016-17 Directory of Ohio Newspapers and Websites Ohio Newspaper Association Staff Ohio Newspaper Association Officers

OHIO NEWSPAPER ASSOCIATION 2016-17 Directory of Ohio Newspapers and Websites Ohio Newspaper Association Staff www.OhioNews.org Ohio Newspaper Association Officers Executive Director President Vice-President Treasurer Dennis Hetzel Bill Southern Monica Nieporte Ron Waite Ext. 1016, [email protected] The Blade Athens Messenger Cuyahoga Falls Toledo, OH Athens, OH News-Press Manager of Administrative Services Kent, OH Sue Bazzoli Ext. 1018, [email protected] Manager of Communication and Content Jason Sanford Ext. 1014, [email protected] Receptionist & Secretary Ann Riggs Secretary & General Counsel Ext. 1010, [email protected] Executive Director Michael Farrell Dennis Hetzel Baker & Hostetler Ohio Newspaper Assoc. Cleveland, OH AdOhio Staff Columbus, OH www.AdOhio.net Ohio Newspaper Association Trustees Terry Bouquot Karl Heminger Josh Morrison Cox Media Group Ohio (past president) Ironton Tribune Dayton OH The Courier Ironton OH Findlay, OH Scott Champion Tim Parkison Clermont Sun Rick Green Sandusky Register Batavia, OH Enquirer Media Sandusky OH Cincinnati OH Karmen Concannon George Rodrigue Sentinel-Tribune Brad Harmon The Plain Dealer Bowling Green OH Dispatch Media Group Cleveland, OH Columbus OH Christopher Cullis Bruce Winges Advertising Director Byran Times Paul Martin Akron Beacon Journal Walt Dozier Bryan OH The Chronicle Telegram Akron, OH Ext. 1020, [email protected] Elyria OH Larry Dorschner Deb Zwez Lisbon Morning Journal Nick Monico The Community Post Operations Manager Lisbon, OH Delaware Gazette Minster OH Patricia Conkle Delaware, OH Ken Douthit Ext. 1021, [email protected] Douthit Communications Sandusky, OH Network Account Executive & Digital Specialist Mitch Colton Ext. 1022, [email protected] Directory Access Graphic Designer and Quote Specialist You can access this directory digitally anytime throughout the Josh Park year on the ONA website: Ext. -

Celebrate the Arts

University of Dayton eCommons News Releases Marketing and Communications 3-1-2010 Celebrate the Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls Recommended Citation "Celebrate the Arts" (2010). News Releases. 1237. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/news_rls/1237 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marketing and Communications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in News Releases by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 11/13/13 University of Dayton : News : 2010 Celebration of the Arts University of Dayton, Ohio (url: http://w w w .udayton.edu/index.php) Celebrate the Arts 03.01.2010 | Fine Arts The University of Dayton is offering the public a free sample of the best its arts students have to offer. The annual Celebration of the Arts: Opening Performance is scheduled for 8 p.m. Tuesday, March 16, at the Schuster Performing Arts Center, One West Second St., downtown Dayton. The program highlights the University's diverse range of arts studies. It will feature performances by University of Dayton music, theatre and dance students as well as visual arts displays in the lobby and faculty performances at a pre-show in the Wintergarden. Neal Gittleman, music director of the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra, will serve as master of ceremonies. The program is free and open to the public, but tickets are required. Call 937-229-2545 or reserve tickets online at the related link. Free transportation is available by RTA bus at 6:45 and 7:20 p.m. -

Newspapers Around Ohio and How to Contact for Letters

NEWSPAPERS AROUND OHIO AND HOW TO CONTACT FOR LETTERS TO EDITOR Akron Beacon Journal: Send letter to: [email protected] Alliance Review: Use this form. Ashland Times-Gazette: Use this form. Ashtabula Star-Beacon: Use this form. Athens Messenger: Send letter to: [email protected] Athens News: Use this form. Bellefontaine Examiner: Send letter to: [email protected] Bellevue Gazette: Use this form. Bowling Green Sentinel-Tribune: Use this form. Bryan Times Send: Use this form. Bucyrus Telegraph-Forum: Use this form. Canton Repository: Use this form. Chillicothe Gazette: Use this form. Cincinnati Enquirer: Use this form. Cleveland Plain Dealer: Use this form. Columbus Dispatch: Use this form or send letter to: [email protected]. Coshocton Tribune: Use this form. Daily Advocate: Use this form. Daily Chief Union: Use this form. Daily Court Reporter: Send letter to: [email protected] Daily Jeffersonian: Use this form. Daily Standard: Send letter to: [email protected] Dayton Daily News: Use this form. Defiance Crescent-News: Use this form. Delaware Gazette: Use this form. Elyria Chronicle-Telegram: Send letter to: [email protected] Fairborn Daily Herald: Use this form. Findlay Courier: Use this form. Fremont News-Messenger: Use this form. Gallipolis Daily Tribune: Use this form. Medina Gazette: Send letter to: [email protected] Hamilton Journal-News: Use this form. Hillsboro Times-Gazette: Use this form. Ironton Tribune: Use this form. Kenton Times: Use this form. Lancaster Eagle-Gazette: Use this form. Lima News: Use this form. Lisbon Morning Journal: Use this form. Logan Daily News: Use this form. Lorain Morning Journal: Send letter to: [email protected] Marietta Times:Use this form. -

The Round Tablette Founding Editor: James W

The Round Tablette Founding Editor: James W. Gerber, MD (1951–2009) 9 February 2012 location, fuel status, etc. in every message. 25:07 Volume 20 Number 7 Given the volume of the messages, the RN Published by WW II History Round Table presumed they contained information Edited by Dr. Joe Fitzharris helpful to the Allied cause. The British www.mn-ww2roundtable.org project, based at Bletchley Park, utilized Thursday, 9 February 2012 highly skilled engineers, physicists, mathematicians, and statisticians, and Welcome to the February meeting of developed calculating machines, called the Harold C. Deutsch World War II “bombes,” for this work. These were highly History Round Table. Tonight, our topic specialized devices for code-breaking, and is the importance of code-breaking for the like most early “computers,” were tailored development of computers, particularly the to specific tasks. Success meant knowing computer industry in Minnesota. Pioneer where U-boats were – convoys could be re- members of the electronic computer industry routed around wolfpacks and anti- join our speaker, Colin Burke, to discuss submarine destroyers and destroyer escorts their roles in this industry. could be vectored to attack the wolfpack to the great happiness of Allied mariners. Before World War II began, the Army and Navy were both trying to break Japanese The British had produced several bombes, diplomatic, military, and naval codes. In each more sophisticated, but at ever Europe, the Poles had obtained copy of a increasing cost in resources. Americans, German ENIGMA machine and were trying peripherally involved in this effort prior to to solve its mysteries. They passed both US entry into the 1939-1945 European machine and a copy of their work to British War, now became junior partners in Intelligence shortly before Poland fell to the developing new bombes.