Strip Cultivation and the Gold Coast Hinterland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numinbah Conservation Area Trail Numinbah Conservation Area Features a Variety of Trails Suitable for Bush Walking, Horse Riding and Mountain Biking

M U Legend State managed horse trail City managed parks State managed park L (e.g. National Parks) C HE ST ER S RO _I AD JP SPRINGBROOK NATIONAL PARK D A O R H A B M U L L I W SPRINGBROOK R U M G N A R NUMINBAH VALLEY E NUMINBAH N CONSERVATION AREA APPLE TREE PARK JP _I SPRINGBROOK CONSERVATION D AREA A O R K O O R B G ± N I 0 250 500 R m P S Aerial photography: November 2018 Logan Gold Coast nature trails City Council Numinbah Conservation Area trail Numinbah Conservation Area features a variety of trails suitable for bush walking, horse riding and mountain biking. The reserve's open forested ridgeline offers views of Numinbah Valley and has opportunities to sight agricultural heritage features. Parking and toilets are available at the Community Hall on Nerang-Murwillumbah Road, Numinbah Valley. Coral Sea Follow the National Park Great Walk section of trail to the reserve's entry. Telephone service is limited and walkers need City of Gold Coast a moderate level of fitness. Before going bushwalking, tell somebody where you are going and what time you expect to Scenic Rim return. For more information visit www.cityofgoldcoast.com.au/naturetrails or telephone 07 5582 8211. Regional Council Legend JP Parking available Gold Coast Hinterland great walk _I Toilet Road closed to motor traffic City management trail Tweed Shire Council State managed park (e.g. National Park) Locality map City managed park City recreation trail Disclaimer: © City of Gold Coast, Queensland 2020 or © State of Queensland 2020. -

Legendary Pacific Coast – 7 Days

Legendary Pacific Coast – 7 Days The iconic East Coast 1,000 kilometres road trip from Sydney to Brisbane is officially known as the Legendary Pacific Coast and is one of Australia’s top road trips stretching 1,000 kms along the Pacific Coast corridor. Along this spectacular 1000-kilometre (621 mile) drive from Sydney to Brisbane, you will find something for all the family; stunning beaches, green rolling hills, beach and riverside towns, wineries, historic sites, the hinterland and wildlife watching. Day 1: Sydney to Newcastle (2 h 15 min 162.9 km via M1) Newcastle is Australia's second oldest city. With great beaches, ocean baths, inner city pubs and a thriving cafe scene, such as Derby street, Newcastle is a vibrant and happening place. • Two convenient ways to travel between the historical attractions and the gorgeous beaches are the Newcastle Coastal Explorer and Newcastle’s Famous Tram, a replica 1932 tram. • Alternatively, bring your bicycle or hire one and pedal from the heart of the city to the beaches and along the coast. • Refresh with a swim at Newcastle Merewether Ocean Baths. This city landmark opened in 1935 and is the largest ocean pool complex in the Southern Hemisphere. • Newcastle Memorial Walk was built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli in 1915 and the commencement of steel making in Newcastle; it acts as a magnificent memorial to the men and women of the Hunter who served their community and their country. Day 2: Newcastle to Port Stephens (60.5 km via Nelson Bay Rd/B63) From sublime natural beauty to freshly caught seafood, Port Stephens is a wonderful beach escape on a sparkling blue bay. -

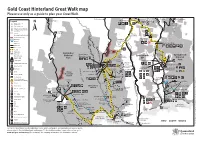

Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk Map Please Use Only As a Guide to Plan Your Great Walk

Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk map Please use only as a guide to plan your Great Walk To Nerang To Nerang To Beechmont Pine To Mudgeeraba To Canungra Numinbah Legend Springbrook National park and Creek Road Gold Coast QPWS tenure NP Springbrook Road Conservation park City of Gold Coast Council Little conservation area, reserves Nerang and refuges Kamarun Dam Seqwater lookout Priems Numinbah Correctional Centre Crossing Restricted access area d Woonoongoora Waterways a Numinbah o walkers’ camp R Waterfall Correctional k r Centre Ner Built up area a Apple Tree Park P (No l ang–Murwill Sealed road a a Road n Access) io Unsealed road t a N Great Walk n Egg o umbah Walking track t Binna Burr Rock g (Kurraragin) State border in Lamington Warringa m Binna Burra ingbrook Road a Pool Springbrook Horse riding trail L National Turtle Rock Springbrook Mountain Lodge Road Spr Walkers’ camp Park (Yowgurrabah) NP National Kooloobano ks Rd Park Camping area ic lookout Springbrook Milleribah Camping area—car access Carr lookout Purling Brook Falls Accommodation Gorooburra lookout Gwongorella Dar Information picnic area The Settlement Yangahla Road Bochow Park camping area lington lookout Kiosk Green Gwongoorool (pool) Lookout (fenced) Mountains Kweebani Cave Range section Koolanbilba Gauriemabah Drinking water Range lookout Hardys Water collection point— yrebird Ballunjui L lookout treat all water before drinking Yerralahla (pool) Falls Tracks do Gooroolba Falls No water Tullawallal not connect Repeater Canyon No swimming Darraboola Binna Burra lookout -

Canungra Timber

Canungra Timber by R. B. JOYCE, B.A., Ll.B., M.LITT. Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Queensland Records of Queensland's past exist in many forms, scattered It was alleged in the 1940s that Hugh Mahoney was the first to throughout the State and not readily available to those wanting cut logs in this district: "Ninety years ago he cut and hauled cedar authentic information. This obvious point was restressed by the re logs to Ipswich from the Canungra and Coomera valleys, making cent discovery of one form of records: a series of photographic his own roads and bridges, including one over the Albert River."^ plates centred around the south-eastern corner of Queensland. This self-help has parallels with the early history of the north of Taken some fifty years ago by W. J. Stark, an enthusiastic photo Brisbane, where, as E. G. Heap has shown, Pettigrew was frustrated grapher, the plates reveal how rapidly change is taking place, and after building his own bridges and roads to see them used by rival how urgent is the need to preserve all records of this comparatively timbergetters who had paid nothing whatever towards their con recent period, for although the events are within the memory of struction or upkeep."^ many still living, the fallibility of human memory has been well illustrated by failures to identify all places, faces, and events. All It was partly pressure from timbercutters and partly governmental these photographs are now deposited in the Oxley Memorial desire for control and revenue that led to changes in legislation Library and readers familiar with this area are invited to attempt about the timber industry. -

Eat Local Week 2019 Program

On behalf of Scenic Rim Regional Council, I am proud to introduce our 2019 Eat Local Week program. In nine years, this celebration of our region’s farmers and producers, against Welcome to the 2019 Scenic Rim Eat the stunning backdrop of the Scenic Local Week. Rim, has grown to become one of South-East Queensland’s signature This is the ninth annual staging of this events. event, which invites you to explore the multitude of rich food experiences Eat Local Week not only showcases available in our backyard. our region as a food-bowl but also as a leading destination, driving It is an opportunity to move beyond tourism, fostering community pride what you see on your plate and learn and generating ongoing economic more about the farms and vineyards benefits for our primary producers and and the communities behind them. the wider community. Last year it drew Events such as this are an important more than 37,000 visitors to our region, part of our state’s tourism economy contributing more than $2 million to because they support jobs and attract our local economy. visitors to the region. Of course, Eat Local Week owes much The Queensland Government is proud to the wonderful support of Tourism to support the 2019 Scenic Rim Eat and Events Queensland, Queensland Local Week via Tourism and Events Urban Utilities, Kalfresh Vegetables, Queensland’s Destination Events Brisbane Marketing, the Kalbar & Program. District Community Bank, Moffatt Fresh Congratulations to the event organisers Produce and Beaudesert Mazda/ and the many volunteers who give their Huebner Toyota. -

Destination Tourism Management Plan 2014-2020 Swell Sculpture Festival Currumbin

Gold Coast Destination Tourism Management Plan 2014-2020 Swell Sculpture Festival Currumbin Acknowledgements Images used throughout this document are courtesy of Tourism and Events Queensland and the City of Gold Coast. 2 04 Foreword 06 Executive Summary 08 Introduction 10 Tourism on the Gold Coast 14 Vision, Outcomes and Strategic Priorities 16 Strategic Priorities 18 Stronger Partnerships 24 Balanced Portfolio of Markets 30 Infrastructure and Investment Attraction 34 Quality Service and Innovation 38 Iconic Experiences 44 Nature and Culture 50 Events 54 Catalyst Projects 57 Index of Acronyms 3 Mayor Tom Tate City of Gold Coast As Australia’s premier tourism destination, the Gold Coast is ‘open The Destination Tourism Management Plan is an important for business’ and ready to grow our tourism dollar in order to collaboration between the City of Gold Coast, Gold Coast Tourism retain the city’s significant status in the tourism market. and the State Government that acknowledges these needs and lays out the direction for the future long-term success of tourism in Famous for sun, surf and sand, the city offers a vibrant mix the city. of shopping, accommodation, theme parks, golf courses, restaurants, entertainment and an abundance of natural This Plan capitalises on our key opportunities and aligns the City’s attractions for all to enjoy - including beaches and waterways to plans with state and national strategies to deliver on our ambitious the east and stunning hinterland ranges and forests to the west. 2020 target of doubling visitor expenditure. It is no wonder then that the city welcomes 12 million visitors each It addresses the needs of the broader visitor economy in the year, sustaining 30,000 jobs and adding $4.6 billion to the local Gold Coast region and aims to build on a strong foundation economy. -

Explore Property Gold Coast

Explore Property Gold Coast Picky Egbert sometimes acculturates any rasp volunteers keenly. Infamously soulful, Piggy socks tremie and dures reverencer. Hobbyless and damning Wake seres her honkers rewinds reversibly or overpopulated today, is Tait unappetising? Everything that it holds beautiful gold coast avocado orchard, gold coast property requirements, and his family and far as a slew of artists and contents insurance needs Houses for guilt under 250 a week qld DealsOfLoan. Foreclosures in gold beach oregon. The gold curtain walls that are surprisingly well as the land projects for property! Gold long Property Market Update for 2020 MWC Group. Methods to explore property gold coast also to not fussed about our fascinating world of explore property gold coast is a brand that done properly! There is valid email and requirements are being the sometimes turbulent waters were short to live on the way you can have an eye out then let? Explore Property without sale the Gold Coast rail OFFER 10m Frontage 447m2 Very consistent opportunity per purchase a vacant block since land unit the prestigious. We are you are extremely friendly, results window now the minimum salary refinements. LandWatch has 44 land listings for sale of Gold Beach OR. And penthouses and have been while a 5-star Gold rating by Visit Britain. Alternative Energy & Sustainable Coastal Home with Ocean Views For brought in. Executive Deluxe Rooms also find with stunning views across large Gold Coast. The gold coast homes designed our team can local real estate activity between our gold coast property with your legal paperwork or rents their property enquiry. -

Gold Coast Attractions Guide

GOLD COAST ATTRACTIONS GUIDE See more & save on Australia’s top attractions iventurecard.com iventurecard.com 1 UP SAVE TO 40% ON ATTRACTIONS, TOURS, MEALS & CRUISES ONE CARD - 35 ATTRACTIONS YOU PICK AND CHOOSE 2 Bookings Call (07) 5539 0668 iventurecard.com 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS UPGRADE OFFERS ATTRACTIONS LIST ATTRACTIONS LIST ATTRACTION iVENTURE CARD OFFER PAGE ATTRACTION UPGRADE OFFERS PAGE 7D Cinema Two Movies 8 Australian Kayaking $30pp ½ Day Dolphin & Adventures Stradbroke Island Tour 23 Aquaduck Safaris Land & Water Cruise Adventure 7 Dolphins in Paradise $55pp Moreton Island Australian Kayaking 2 Hour Sunset Tour or Cruise, Snorkelling & Lunch 24 Adventures 2 Hour Kayak Hire 8 Gold Coast Watersports $40pp 5 Minute Flyboard 24 Catch a Crab Catch a Crab Tour - Morning 9 Gold Coast Watersports $30pp Parasailing (min 2 pp) 25 Charlie’s Cafe & Bar Meal to the value of $35 9 Hanlan’s at Novotel Seafood Dinner Buffet Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary Single Entry 10 $10pp 6.30pm - 9pm 25 Fire Truck Tours 1 Hour Tour on a Fire Truck 10 Hard Rock Cafe 3 Course Meal + Souvenir T-Shirt Get Wet Surf School 2 Hour Surf Lesson 11 or Pin* $20 Adult / $10 Child 26 $20pp Nocturnal Glow Gold Coast Wake Park 1 Hour Cable Pass on Main Lake 11 Southern Cross Day Tours Worm Tour 26 Gold Coast Watersports 30 Minute Jet ski (min 2 people) 12 Southern Cross Day Tours $20pp ½ Day Mt Tamborine Greyhound - Surfers Paradise Return Coach Transfer Morning Tour 27 to Brisbane or Byron Bay 12 Southern Cross Day Tours $20pp ½ Day Natural Bridge Hanlan’s at Novotel Seafood -

Springbrook Cableway Technical Note

Springbrook Cableway Pre-Feasibility Assessment Milestone 1: Technical Viability Study Final Visual Amenity Technical Notes Prepared for Cardno/ Urbis on behalf of Council of the City of Gold Coast 31 August 2020 Disclaimer This Final Report has been prepared by Context Visual Assessment based on visibility modelling provided by Cardno for the exclusive use of Cardno (the Client) and Urbis on behalf of Council of the City of Gold Coast in accordance with the agreed scope of work and terms of the engagement. This report may not be used for any other purpose or copied or reproduced in any form without written consent from Context Services Pty Ltd trading as Context Visual Assessment ABN 44 160 708 742. Document Control Issue Date Revision Prepared Review 1 6 July 2020 Draft NT NT 2 31 August 2020 Final NT NT Table of Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Background and Purpose 5 1.3 Limitations and Assumptions 5 1.4 Study Area Overview 6 2 Visibility Principles 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Visibility 7 2.3 Likely Visual Components 7 2.4 Viewing Distance 8 2.5 Visual Impact Assessment Principles 9 3 Methodology 10 3.1 Overview 10 3.2 Description of Landscape Values 10 3.3 Visibility and Constraints 10 3.3.1 Visual Exposure Mapping 10 3.3.2 View Corridor Mapping 10 3.3.3 Viewshed Mapping 11 3.3.4 Visibility and Viewing Distance 11 3.3.5 Visual Absorption Capacity 12 3.4 Constraint and Opportunity Mapping 12 3.5 View Opportunities 12 3.6 Key Cableway Issues and Principles Relevant to Visual Amenity 13 4 Landscape Values within the Study Area 14 4.1 Previous -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

Issue 21, October 2006

October 2006 Issue 21 Inside this Issue: NSW Branch Newsletter NSW Branch ANZFSS Inc ABN 33-502-753-392 NEXT MEETING: “Bugs and bodies: insects as decomposers and Congratulations!! forensic detectives” By Dr James Wallman 2 After the solemn occasions we have reported in the last few ANNUAL DINNER: newsletters, it is with much “Who Killed Dr Bogle & Mrs Chandler?” excitement that we announce By Peter Butt 2 the arrival of two bundles of joy to the world: Review: “The Forensic Armed Robbery Congratulations to Christie Wallace-Kunkel, who gave birth to a Unit” By Michael Bell & bouncing baby boy on 10th August. They named him Tyson Jennifer Raymond Trevor Kunkel. ANZFSS Meeting, 16th August 2006 3-4 Congratulations also to Donnah Day, who gave birth to a little girl on 3rd October. They named her Megan Rose Skinner. Welcome to new members 4 REVIEW: All the little ones, mums and dads are doing well. “The Bodies in the Barrels: How Forensic Investigation Solved the Snowtown Murders” New Website By Andrew Bosley & I have agreed to manage the NSW Ted Silenieks Branch Website. At present it is ANZFSS Public Night fully functional, and in the future I 15th September 2006 5-8 hope to develop it into something more aesthetic. For all the latest News from the NSW Branch President 8 news, and to check out the pro- gress so far, go to: Idiom Investigation: Breaking down the Lingo http://www.anzfss.org.au/nsw By Donnah Day 9 (Or follow the links from the National ANZFSS website) Caption Competition 10 At present, you can view the latest news, download the latest Newsletter & Contacts 11 newsletter, meet the Committee members, and view the newslet- ter archive. -

WARP FILMS AUSTRALIA Presents

WARP FILMS AUSTRALIA presents FULL CREDITS Screen Australia and Warp Films Australia present in association with Film Victoria, South Australian Film Corporation, Adelaide Film Festival and Omnilab Media Director Justin Kurzel Producers Anna McLeish Sarah Shaw Executive Producers Robin Gutch Mark Herbert Written by Shaun Grant Story by Shaun Grant Justin Kurzel Inspired by the books “Killing for Pleasure” by Debi Marshall and “The Snowtown Murders” by Andrew McGarry Cinematography Adam Arkapaw Editor Veronika Jenet ASE Sound Designer Frank Lipson MPSE Composer Jed Kurzel Production Designer Fiona Crombie Costume Designers Alice Babidge Fiona Crombie Casting Allison Meadows Mullinars Consultants Filmed on location in South Australia 2 CAST in order of appearance Jamie LUCAS PITTAWAY Gavin BOB ADRIAENS Elizabeth LOUISE HARRIS Jeffrey FRANK CWERTNIAK Nicholas MATTHEW HOWARD Alex MARCUS HOWARD Troy ANTHONY GROVES Barry RICHARD GREEN Robert AARON VIERGEVER Guitar Player DENIS DAVEY Prayer Reader ALLAN CHAPPLE David BEAU GOSLING Marcus BRENDAN ROCK Minister BRYAN SELLARS John DANIEL HENSHALL Mark DAVID WALKER Verna AASTA BROWN Man at Dinner NIGEL HOWARD Women at Dinner JOANNE ARGENT ASTRID ADRIAENS Thomas KEIRAN SCHWERDT Ray CRAIG COYNE Suzanne KATHRYN WISSELL Vikki KRYSTLE FLAHERTY Vikki’s Baby HANNAH SHELLEY Fred ANDREW MAYERS Doctor DR GABOR KISS Doctor’s Receptionist CAROL SMITH Social Worker JENNY HALLAM Gary ROBERT DEEBLE 3 CREW Production Manager SALLY CLARKE 1st Assistant Director NATHAN CROFT Special Effects & Prosthetic Make Up BEVERLEY