The Functions of the Gaze in Tarantino's Django Unchained

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Inglorious Lstms Generating Tarantino Movies with Neural Networks

Inglorious LSTMs Generating Tarantino Movies with Neural Networks Bohdan Andrusyak Data Scientist at Know Center linkedin.com/in/bandrusyak Today’s Questions ● What is NLP? ● Language Models and Who Needs Them? ● What is better Human Brain or Neural Network? ● Are LSTM similar to LSD? ● How can You do All of This in Python? ● How can You Generate Movie Script? What is NLP? ● NLP - Neuro Linguistic Programing Natural Language Processing ● Sub-field of Artificial Intelligence focused on enabling computers to understand and process human languages ● Applications: ○ Language Translation ○ Sentiment Detection ○ Text Categorization ○ Text Summarization ○ Text Generation Why do computers can not understand humans? Formal Language: Human Language: a = 10 He is literally on fire b = 20 Bring me that thing while a < 20: Great job a += 1 Language Models what are they? ● Statistical Language Model - probabilistic model that are able to predict the next word in the sequence based on previous words. ● Neural Language Model - parametrization of words as vectors (word embeddings) and using them as inputs to a neural network. Parameters are learned during training. Words with same meaning are close in vector space. Word Embeddings Real Life Example Who uses Language Models? ● Word2vec, Google ● BERT, Google ● ELMo, Allen Institute ● GloVe, Stanford ● fastText, Facebook ● GPT2, Open AI (too dangerous to be released) Neuron Activation functions ● Step Function ● Sigmoid Function ● Tanh Function ● ReLU Function Neural Network Recurrent Neural Networks Repeating module in RNN The Problem of Long-Term Dependencies LSTM - Long Short Term Memory LSTM gates LSTM step by step How Can You Do It in Python? NLP libraries: ● nltk - natural language toolkit ● spaCy ● gensim Deep learning: ● TensorFlow ● Keras Finally, some practical stuff Data collection ● Source: imsdb.com ● Movie scripts collected: ○ Natural Born Killers ○ Reservoir Dogs ○ From Dusk till Dawn ○ Pulp Fiction ○ Jackie Brown ○ Kill Bill vol. -

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political by Gordon Sullivan B.A., University of Central Florida, 2004 M.A., North Carolina State University, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Gordon Sullivan It was defended on October 20, 2017 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Daniel Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Gordon Sullivan 2017 iii “NO REASON TO BE SEEN”: CINEMA, EXPLOITATION, AND THE POLITICAL Gordon Sullivan, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 This dissertation argues that we can best understand exploitation films as a mode of political cinema. Following the work of Peter Brooks on melodrama, the exploitation film is a mode concerned with spectacular violence and its relationship to the political, as defined by French philosopher Jacques Rancière. For Rancière, the political is an “intervention into the visible and sayable,” where members of a community who are otherwise uncounted come to be seen as part of the community through a “redistribution of the sensible.” This aesthetic rupture allows the demands of the formerly-invisible to be seen and considered. We can see this operation at work in the exploitation film, and by investigating a series of exploitation auteurs, we can augment our understanding of what Rancière means by the political. -

Birth, Django, and the Violenceof Racial Redemption

religions Article Rescue US: Birth, Django, and the Violence of Racial Redemption Joseph Winters Religious Studies, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA; [email protected] Received: 19 December 2017; Accepted: 8 January 2018; Published: 12 January 2018 Abstract: In this article, I show how the relationship between race, violence, and redemption is articulated and visualized through film. By juxtaposing DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, I contend that the latter inverts the logic of the former. While Birth sacrifices black bodies and explains away anti-black violence for the sake of restoring white sovereignty (or rescuing the nation from threatening forms of blackness), Django adopts a rescue narrative in order to show the excessive violence that structured slavery and the emergence of the nation-state. As an immanent break within the rescue narrative, Tarantino’s film works to “rescue” images and sounds of anguish from forgetful versions of history. Keywords: race; redemption; violence; cinema; Tarantino; Griffith; Birth of a Nation; Django Unchained Race, violence, and the grammar of redemption form an all too familiar constellation, especially in the United States. Through various narratives and strategies, we are disciplined to imagine the future as a state of perpetual advancement that promises to transcend legacies of anti-black violence and cruelty. Similarly, we are told that certain figures or events (such as the election of Barack Obama) compensate for, and offset, the black suffering that -

Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Special Topics in Film)

RACE & GENDER IN AMERICAN FILM (SPECIAL TOPICS IN FILM) Fall 2020 Synchronous Remote Course Mondays 6:00pm-9:00pm (Eastern Time Zone) Course Numbers: 21:014:255:02/21:350:363:01 Rutgers University-Newark Professor: Dr. Lyra D. Monteiro Email: [email protected] Google Hangouts: [email protected] Video Office Hours: Tuesdays, 4:00-5:00pm (Eastern Time Zone), Wednesdays 5:30-6:30pm (Eastern Time Zone), and by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION This summer’s uprisings were sparked by a number of widely circulating videos in which a white man or woman kills (or in some cases, nearly kills) a Black man or woman. We will not be watching these horrific videos in this course. What we will be doing is studying the ways in which movies that may seem like frivolous fun are actually part of the story as to how these events came to occur. Movies teach every one of us how to “be” the race and gender assigned to us by this society—and how to think about, feel towards, and treat those who are assigned to other races and genders. We will also be looking at how filmmakers who hold marginalized identities have, in recent years, made movies that actively seek to address the disastrous racial violence in the United States. During the first part of the term, we will use films to learn and practice tools for analyzing how race, gender, and sexual orientation function in film—and how this shapes privilege and oppression in the real world. The remainder of the course looks at films from the past few years, seeking to understand and compare the different choices that their (mostly Black) creators made—in terms of different genres, settings, styles, etc.—in order to engage with present-day issues of anti-Blackness. -

A Look Into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2018 The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Necaise, Justin Tyler, "The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino" (2018). Honors Theses. 493. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/493 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CINEMATIC SOUTH: A LOOK INTO THE SOUTH ACCORDING TO QUENTIN TARANTINO by Justin Tyler Necaise A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2018 Approved by __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Andy Harper ___________________________ Reader: Dr. Kathryn McKee ____________________________ Reader: Dr. Debra Young © 2018 Justin Tyler Necaise ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii To Laney The most pure-hearted person I have ever met. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family for being the most supportive group of people I could have ever asked for. Thank you to my father, Heath, who instilled my love for cinema and popular culture and for shaping the man I am today. Thank you to my mother, Angie, who taught me compassion and a knack for looking past the surface to see the truth that I will carry with me through life. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Westerns…All'italiana

Issue #70 Featuring: TURN I’ll KILL YOU, THE FAR SIDE OF JERICHO, Spaghetti Western Poster Art, Spaghetti Western Film Locations in the U.S.A., Tim Lucas interview, DVD reviews WAI! #70 The Swingin’ Doors Welcome to another on-line edition of Westerns…All’Italiana! kicking off 2008. Several things are happening for the fanzine. We have found a host or I should say two hosts for the zine. Jamie Edwards and his Drive-In Connection are hosting the zine for most of our U.S. readers (www.thedriveinconnection.com) and Sebastian Haselbeck is hosting it at his Spaghetti Westerns Database for the European readers (www.spaghetti- western.net). Our own Kim August is working on a new website (here’s her current blog site http://gunsmudblood.blogspot.com/ ) that will archive all editions of the zine starting with issue #1. This of course will take quite a while to complete with Kim still in college. Thankfully she’s very young as she’ll be working on this project until her retirement 60 years from now. Anyway you can visit these sites and read or download your copy of the fanzine whenever you feel the urge. Several new DVD and CD releases have been issued since the last edition of WAI! and co-editor Lee Broughton has covered the DVDs as always. The CDs will be featured on the last page of each issue so you will be made aware of what is available. We have completed several interviews of interest in recent months. One with author Tim Lucas, who has just recently released his huge volume on Mario Bava, appears in this issue. -

Two Scoops of Django: Best Practices for Django 1.5 First Edition, Final Version, 20130411 by Daniel Greenfeld and Audrey Roy

Two Scoops of Django Best Practices For Django 1.5 Daniel Greenfeld Audrey Roy Two Scoops of Django: Best Practices for Django 1.5 First Edition, Final Version, 20130411 by Daniel Greenfeld and Audrey Roy Copyright ⃝c 2013 Daniel Greenfeld, Audrey Roy, and Cartwheel Web. All rights reserved. is book may not be reproduced in any form, in whole or in part, without written permission from the authors, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles or reviews. Limit of Liability and Disclaimer of Warranty: e authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, and the information provided herein “as is.” e information provided is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors nor Cartwheel Web will be held liable for any damages to be caused either directly or indirectly by the contents of this book. Trademarks: Rather than indicating every occurence of a trademarked name as such, this book uses the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benet of the trademark owner with no intention of infringement of the trademark. First printing, January 2013 For more information, visit https://django.2scoops.org. For Malcolm Tredinnick 1971-2013 We miss you. iii Contents List of Figures xv List of Tables xvii Authors’ Notes xix A Few Words From Daniel Greenfeld . xix A Few Words From Audrey Roy . xx Introduction xxi A Word About Our Recommendations . xxi Why Two Scoops of Django? . xxii Before You Begin . xxiii is book is intended for Django 1.5 and Python 2.7.x . xxiii Each Chapter Stands On Its Own . -

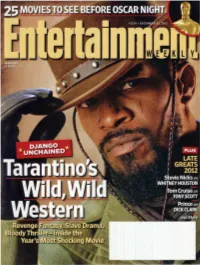

Django Unchained (Rated R) Under the Tree on Dec

-UENTIN TARANTINO knows the.secret of yuletide gift giving: Get them something they wouldn't get thf ~selves. After all, who but Tarantino, the man who achine-gunned Hitler's face off in his WWII remix (jfiourious Basterds, would think of laying a hyper- violent all-star slave-revenge-Western fairy tale like Django Unchained (rated R) under the tree on Dec. 25? Like so,many other presents, Django was wrapped just in time. After seven months of production, additional reshoots, weather complications, a revolving-door cast list, a sudden death, and a sprint to the finish in the editing room, Tarantino has managed to deliver the film for its festive release date. With that long, dusty trail now behind , him, the filmmaker slumps beneath a foreign-language . ' \Pulp Fiction poster in a corner of Do Hwa, the Korean l ' l ◄ , 1 , ~staurant he co-owns in Manhattan's West Village, and ' t av mits he's tired. "It's been a long journey, man." I i I , 26 I EW.COM Dec,a 21, 2012 (Clockwise from far left) Foxx; Foxx, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Waltz; Kerry Washington and Samuel L. Jackson; Washington Keep in mind: An exhausted Quentin Tarantino, even at 49 and a long way from his wunderkind years, is still as energetic as a regular person would be after two strong coffees. And he's char acteristically enthusiastic about his new film: a spaghetti Western silent. To a degree, Tarantino understands the response. "There transposed to the antebellum South that follows a slave (Jamie is no setup for Django, for what we're trying to do. -

The South According to Quentin Tarantino

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The South According To Quentin Tarantino Michael Henley University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Henley, Michael, "The South According To Quentin Tarantino" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 887. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/887 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOUTH ACCORDING TO QUENTIN TARANTINO A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture The University of Mississippi by MICHAEL LEE HENLEY August 2015 Copyright Michael Lee Henley 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This thesis explores the filmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s portrayal of the South and southerners in his films Pulp Fiction (1994), Death Proof (2007), and Django Unchained (2012). In order to do so, it explores and explains Tarantino’s mixture of genres, influences, and filmmaking styles in which he places the South and its inhabitants into current trends in southern studies which aim to examine the South as a place that is defined by cultural reproductions, lacking authenticity, and cultural distinctiveness. Like Godard before him, Tarantino’s movies are commentaries on film history itself. In short, Tarantino’s films actively reimagine the South and southerners in a way that is not nostalgic for a “southern way of life,” nor meant to exploit lower class whites.