A Reassessment of the Tank Battle Between 4Th Armoured Brigade and Panzerregiment 5 During Operation Crusader in North Africa on 19 November 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette

tftnmb 37655 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the i6th of JULY, 1946 by Registered as a newspaper WEDNESDAY, 17 JULY, 1946 The War Office,' July, 1946 OPERATIONS OF EAST AFRICA COMMAND, I2TH JULY, 1941 TO 8xH JANUARY, 1943 The following Despatch was submitted on area where General Nasi's forces were still March, 1943, to the Secretary of State for holding out, organised resistance in Ethiopia War by LIEUT.-GENERAL SIR WILLIAM had ceased prior to my predecessor's last PLATT, G.B.E., K.C.B., D.S.O., General despatch which dealt with operations up to the Officer Commanding in Chief, East Africa nth of July, 1941. Command. Although military opposition by .Italian On I5th September, 1941, East Africa Force forces had been almost eliminated, the main- as part of. Middle East Forces was abolished tenance of law and order over more than half and replaced by East Africa Command directly a million square miles of conquered territory under the War Office, covering the territories presented no small problem. The country was from Eritrea in the North to the Zambesi in armed from North to South and from East to the South. My predecessor Lieut.-General Sir West, with rifles, ammunition, grenades and Alan Cunningham, K.C.B., D.S.O., M.C., many automatics. More than 20,000 rifles, left East Africa on 29th August, 1941, to with over 20 million rounds of ammunition had assume command of the Eighth Army in been pumped into Ethiopia from the Sudan Middle East. Until my arrival on 5th Decem- alone to aid the Patriots in their revolt against ber, 1941, Major-General H. -

Medical Conditions in the Western Desert and Tobruk

CHAPTER 1 1 MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN THE WESTERN DESERT AND TOBRU K ON S I D E R A T I O N of the medical and surgical conditions encountered C by Australian forces in the campaign of 1940-1941 in the Wester n Desert and during the siege of Tobruk embraces the various diseases me t and the nature of surgical work performed . In addition it must includ e some assessment of the general health of the men, which does not mean merely the absence of demonstrable disease . Matters relating to organisa- tion are more appropriately dealt with in a later chapter in which the lessons of the experiences in the Middle East are examined . As told in Chapter 7, the forward surgical work was done in a main dressing statio n during the battles of Bardia and Tobruk . It is admitted that a serious difficulty of this arrangement was that men had to be held for some tim e in the M.D.S., which put a brake on the movements of the field ambulance , especially as only the most severely wounded men were operated on i n the M.D.S. as a rule, the others being sent to a casualty clearing statio n at least 150 miles away . Dispersal of the tents multiplied the work of the staff considerably. SURGICAL CONDITIONS IN THE DESER T Though battle casualties were not numerous, the value of being able to deal with varied types of wounds was apparent . In the Bardia and Tobruk actions abdominal wounds were few. Major J. -

Brevity, Skorpion & Battleaxe

DESERT WAR PART THREE: BREVITY, SKORPION & BATTLEAXE OPERATION BREVITY MAY 15 – 16 1941 Operation Sonnenblume had seen Rommel rapidly drive the distracted and over-stretched British and Commonwealth forces in Cyrenaica back across the Egyptian border. Although the battlefront now lay in the border area, the port city of Tobruk - 100 miles inside Libya - had resisted the Axis advance, and its substantial Australian and British garrison of around 27,000 troops constituted a significant threat to Rommel's lengthy supply chain. He therefore committed his main strength to besieging the city, leaving the front line only thinly held. Conceived by the Commander-in-Chief of the British Middle East Command, General Archibald Wavell, Operation Brevity was a limited Allied offensive conducted in mid-May 1941. Brevity was intended to be a rapid blow against weak Axis front-line forces in the Sollum - Capuzzo - Bardia area of the border between Egypt and Libya. Operation Brevity's main objectives were to gain territory from which to launch a further planned offensive toward the besieged Tobruk, and the depletion of German and Italian forces in the region. With limited battle-ready units to draw on in the wake of Rommel's recent successes, on May 15 Brigadier William Gott, with the 22nd Guards Brigade and elements of the 7th Armoured Division attacked in three columns. The Royal Air Force allocated all available fighters and a small force of bombers to the operation. The strategically important Halfaya Pass was taken against stiff Italian opposition. Reaching the top of the Halfaya Pass, the 22nd Guards Brigade came under heavy fire from an Italian Bersaglieri (Marksmen) infantry company, supported by anti-tank guns, under the command of Colonel Ugo Montemurro. -

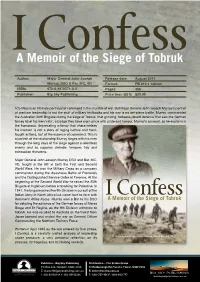

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

(June 1941) and the Development of the British Tactical Air Doctrine

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies A Stepping Stone to Success: Operation Battleaxe (June 1941) and the Development of the British Tactical Air Doctrine Mike Bechthold On 16 February 1943 a meeting was held in Tripoli attended by senior American and British officers to discuss the various lessons learned during the Libyan campaign. The focus of the meeting was a presentation by General Bernard Montgomery. This "gospel according to Montgomery," as it was referred to by Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, set out very clearly Monty's beliefs on how air power should be used to support the army.1 Among the tenets Montgomery articulated was his conviction of the importance of air power: "Any officer who aspires to hold high command in war must understand clearly certain principles regarding the use of air power." Montgomery also believed that flexibility was the greatest asset of air power. This allowed it to be applied as a "battle-winning factor of the first importance." As well, he fully endorsed the air force view of centralized control: "Nothing could be more fatal to successful results than to dissipate the air resource into small packets placed under the control of army formation commanders, with each packet working on its own plan. The soldier must not expect, or wish, to exercise direct command over air striking forces." Montgomery concluded his discussion by stating that it was of prime importance for the army and air 1 Arthur Tedder, With Prejudice: The war memoirs of Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Lord Tedder (London: Cassell, 1966), p. -

The Impact of the Collapse of the Soviet Union on Libya Foreign Policy

The impact of the collapse of the Soviet Union on Libya foreign policy during the period from 1991 to 2003 By Jumah F. Dakheel A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of The Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 School of Arts and Humanities I Abstract One of the most notable events in world politics in the second half of the 20th century was the Soviet Union’s fall in December 1991 which profoundly changed the outlook of the global political scene and the balance of power among its key actors. This thesis studies the impacts and significance of the Soviet demise on Libyan foreign policy between 1991 and 2003. Libyan foreign policy was transformed; the thesis asks how, why and when this occurred and how the changes in foreign policy were managed. While so doing, a set of questions are raised concerning the emerging context and developments in world order which seemed to compel Libya to change its behaviour, changing its relations with the West in general and the United States in particular. Three major questions are explored in detail in this thesis. The first question relates to how and why Libya aligned with the Soviet Union. The second question addresses how and to what extent these developments in international order appeared to have affected Libya’s foreign policy behaviour. Finally, the third question sheds light on the reasons and attitudes that led to these changes in Libya’s foreign policy orientations. This is also to engage with an important literature on the scope of foreign policy of small states. -

Presencia Italiana En La Milicia Española. the Italian

Comisión Revista Internacional de Historia Militar 94 Comisión Internacional Cuaderno de Historia Militar 5 Española de Historia de Historia Militar Presencia italiana Militar en la milicia española The Italian Presence in the Spanish Military José María Blanco Núñez (coord.) MINISTERIO DE DEFENSA Ilustración de cubierta: Bandera de las Reales Guardias Italianas (de- talle) [en J. L. Calvo y L. Grávalos, Banderas de España, Madrid, Sílex ed., 1983, p. 109 n.º 256]. Soldados del Regimiento de Nápoles (siglo XVIII) [en M. Gómez Ruiz y V. Alonso Juanola, Estado Militar Gráfico de 1791, Madrid, 1997, lámina 44]. COMISIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE HISTORIA MILITAR INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF MILITARY HISTORY COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE Presencia italiana en la milicia española The Italian Presence in the Spanish Military José María Blanco Núñez (Coord.) REVISTA INTERNACIONAL DE HISTORIA MILITAR INTERNATIONAL REVIEW OF MILITARY HISTORY REVUE INTERNATIONALE D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE INTERNATIONALE ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR MILITÄRGESCHICHTE RIVISTA INTERNAZIONALE DI STORIA MILITARE 94 N.º 94 – Madrid - 2016 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA Presencia italiana en la Milicia Española = The Italian Presence in the Spanish Military / Comisión Internacional de Historia Militar = International Commission of Military History = Commission Internationale D’Histoire Militaire; José María Blanco Núñez (Coord.) – Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa, Secretaría General Técnica, D.L. 2016. – 264 p.: il.; 17 x 24 cm. – (Cuaderno de Historia Militar; 5). Número 94 de la Revista Internacional de Historia Militar. Bibliografía (p. 193-209) e índice I. Blanco Núñez, José María (1945-), coord. II. Comisión Internacional de Historia Militar III. España. Ministerio de Defensa IV. Título V. Serie 1. España – Fuerzas Armadas – Historia – 1500-2000 2. -

Mind the Uppercase Letters

The Springboks in East Africa: The role of 1 SA Survey Company (SAEC) in the East African Campaign of World War II, 1940-1941 Elri Liebenberg Department of Geography, University of South Africa Abstract. As a member of the British Commonwealth, South Africa was part of Britain’s war effort since September 1939. When Italy entered the War on the side of Germany on 10 June 1940, the Italian territories in East Africa comprised Abyssinia together with Eritrea, now part of Ethiopia, and Italian Somaliland, now part of the Somali Democratic Republic. Although pre-war plans did not anticipate that the SA Army would fight outside southern Africa, Italy’s involvement in north-east Africa made it inevitable that South African troops would be deployed to the new war frontier. The South African forces (commonly known in the media as “Springboks”) played a major role in the fall of Mussolini’s East African Empire. The war was fought under extreme physical circumstances, and it was especially the SAEC (South African Engineering Corps) which rendered invaluable ser- vices. By 1940 East Africa was still largely unmapped, and one of the SAEC units, 1 SA Survey Company (initially named the1st Field Survey Company), supported by 60 Photographic Squadron of the South African Air Force, mapped large parts of the war zone and provided essential military intelli- gence. This paper deals with the formation and subsequent deployment of 1 SA Survey Company in Kenya, Abyssinia and Somaliland, as well as the achie- vements of its various sections. The maps which were produced, are analy- sed against the background of the available source material and prevailing circumstances. -

Casanova, Julían, the Spanish Republic and Civil

This page intentionally left blank The Spanish Republic and Civil War The Spanish Civil War has gone down in history for the horrific violence that it generated. The climate of euphoria and hope that greeted the over- throw of the Spanish monarchy was utterly transformed just five years later by a cruel and destructive civil war. Here, Julián Casanova, one of Spain’s leading historians, offers a magisterial new account of this crit- ical period in Spanish history. He exposes the ways in which the Republic brought into the open simmering tensions between Catholics and hard- line anticlericalists, bosses and workers, Church and State, order and revolution. In 1936, these conflicts tipped over into the sacas, paseos and mass killings that are still passionately debated today. The book also explores the decisive role of the international instability of the 1930s in the duration and outcome of the conflict. Franco’s victory was in the end a victory for Hitler and Mussolini, and for dictatorship over democracy. julián casanova is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Zaragoza, Spain. He is one of the leading experts on the Second Republic and the Spanish Civil War and has published widely in Spanish and in English. The Spanish Republic and Civil War Julián Casanova Translated by Martin Douch CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521493888 © Julián Casanova 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

![7 Armoured Division (1941-42)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4788/7-armoured-division-1941-42-1304788.webp)

7 Armoured Division (1941-42)]

3 September 2020 [7 ARMOURED DIVISION (1941-42)] th 7 Armoured Division (1) Headquarters, 7th Armoured Division 4th Armoured Brigade (2) Headquarters, 4th Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 4th Royal Tank Regiment (3) 5th Royal Tank Regiment (3) 7th Royal Tank Regiment (4) 7th Armoured Brigade (5) Headquarters, 7th Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Royal Tank Regiment 7th Support Group (6) Headquarters, 7th Support Group & Signal Section 1st Bn. The King’s Royal Rifle Corps 2nd Bn. The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) 3rd Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery 4th Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery 1st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Divisional Troops 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s Own) (7) 4th Field Squadron, Royal Engineers (8) 143rd Field Park Squadron, Royal Engineers (8) 7th Armoured Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 3 September 2020 [7 ARMOURED DIVISION (1941-42)] NOTES: 1. This was a regular army division stationed in Egypt. It had been formed as the Mobile Division in September 1938, as a result of the raised tension caused by the Munich Crisis. Initially called the ‘Matruh Mobile Force’, it was founded by Major General P. C. S. HOBART. This is the Order of Battle for the division on 15 May 1941. This was the date of the start of Operation Brevity, the operation to reach Tobruk The division was under command of Headquarters, British Troops in Egypt until 16 May 1941. On that date, it came under command of Headquarters, Western Desert Force (W.D.F.). It remained under command of W.D.F. -

VICTORY at SIDI BARRANI 28 Nov-6 Dec Preparations That Were Being Made Around Them

CHAPTER 6 VICTORY AT SIDI BARRAN I HE stage was now set for the opening of the desert battle which Genera l T Wavell and his subordinates had discussed before the Italian invasion of Greece. Thus far the new theatre of war had made relatively smal l demands on Wavell's and Longmore's forces, and the Italian Army's failure to overcome the Greeks lowered an already low estimate of it s efficiency . Although Western Desert Force was still greatly outnumbered by General Bergonzoli's army, it had received useful reinforcements . It will be recalled that in October two tank regiments from England ha d joined the 7th Armoured Division, bringing its two armoured brigade s each to their proper strength of three regiments ; and the 7th Royal Tank Regiment had arrived, equipped with heavy "Matilda" tanks to be use d with infantry to break into strong defensive positions . In September the 4th Indian Division had been completed by adding to it the 16th Britis h Brigade ; in November its own third brigade arrived . In the Matruh Fortress was assembled a force equal to two infantry brigades . The 4th Ne w Zealand Brigade, had, since September, been in reserve either at Dab a or Bagush ; and on the edge of the Delta were the 6th Australian Division , now more or less complete, and the Polish brigade . Thus in three month s the forces west of Alexandria had increased from two weak divisions t o three at full strength or close to it, plus four infantry brigades ; and within a few weeks the New Zealand and the 7th Australian Divisions woul d be complete, in units if not equipment, and the 2nd Armoured Divisio n would have arrived. -

East Africa Command History & Personnel

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER A CONCISE HISTORY OF: EAST AFRICA COMMAND (HISTORY & PERSONNEL) A concise history of the East Africa Command, a static command in the British Army covering the British colonies in East Africa between 1940 and 1950. In addition, known details of the key appointments held between 1940 and 1950 are included. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 21 January 2020 [EAST AFRICA COMMAND HISTORY & PERSONNEL] The History and Personnel of East Africa Command Version: 1_2 This edition dated: 21 January 2020 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER (copyright held by author) Assisted by: Stephen HEAL Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk ©www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 21 January 2020 [EAST AFRICA COMMAND HISTORY & PERSONNEL] East Africa Command Prior to the Second World War, the United Kingdom had several colonies in East Africa. They were: • Kenya; • Uganda; • British Somaliland; • Nyasaland (now Malawi); • Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia); • Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In the Great War, a long campaign had been fought in German East Africa, and following the Armistice, that country was incorporated into the British Empire as Tanganyika (now Tanzania). Between the two world wars, responsibility for the Army in the colonies of East Africa was devolved to the individual colonies themselves. The various Army regiments in the colonies were amalgamated into the King’s African Rifles in 1902, which after the Great War was reduced to six Regular battalions.