Ask the Rabbi 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

Seudas Bris Milah

Volume 12 Issue 2 TOPIC Seudas Bris Milah SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is a Proofreading: Mrs. EM Sonenblick monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, Website Management and Emails: a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva Heshy Blaustein Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita. Rabbi Dedicated in honor of the first yartzeit of Lebovits currently works as the Rabbinical Administrator for ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. SPONSORED: Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles SPONSORED: discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of לרפואה שלמה ,all relevant shittos on each topic חיים צבי בן אסתר as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current SPONSORED: issues. לעילוי נשמת WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKING מרת בריינדל חנה ע"ה Halachically Speaking is בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט .distributed to many shuls גערשטנער It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far SPONSORED: Rockaway, and Queens, The ,Flatbush Jewish Journal לרפואה שלמה להרה"ג baltimorejewishlife.com, The רב חיים ישראל בן חנה צירל Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2015 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking ח.( )ברכות Seudas Bris Milah בלבד.. -

A Taste of Jewish Law & the Laws of Blessings on Food

A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food (2003 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10018985 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A ‘‘TASTE’’ OF JEWISH LAW -- THE LAWS OF BLESSINGS ON FOOD Jeremy Hershman Class of 2003 April 2003 Combined Course and Third Year Paper Abstract This paper is an in-depth treatment of the Jewish laws pertaining to blessings recited both before and after eating food. The rationale for the laws is discussed, and all the major topics relating to these blessings are covered. The issues addressed include the categorization of foods for the purpose of determining the proper blessing, the proper sequence of blessing recital, how long a blessing remains effective, and how to rectify mistakes in the observance of these laws. 1 Table of Contents I. Blessings -- Converting the Mundane into the Spiritual.... 5 II. Determining the Proper Blessing to Recite.......... 8 A. Introduction B. Bread vs. Other Grain Products 1. Introduction 2. Definition of Bread – Three Requirements a. Items Which Fail to Fulfill Third Requirement i. When Can These Items Achieve Bread Status? ii. Complications b. -

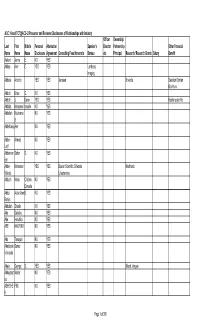

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning

TRANSITIONS & CELEBRATIONS: Jewish Life Cycle Guides E EW A TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning Written and compiled by Rabbi John L. Rosove Temple Israel of Hollywood INTRODUCTION The death of a loved one is so often a painful and confusing time for members of the family and dear friends. It is our hope that this “Guide” will assist you in planning the funeral as well as offer helpful information on our centuries-old Jewish burial and mourning practices. Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary (“Hillside”) has served the Southern California Jewish Community for more than seven decades and we encourage you to contact them if you need assistance at the time of need or pre-need (310.641.0707 - hillsidememorial.org). CONTENTS Pre-need preparations .................................................................................. 3 Selecting a grave, arranging for family plots ................................................. 3 Contacting clergy .......................................................................................... 3 Contacting the Mortuary and arranging for the funeral ................................. 3 Preparation of the body ................................................................................ 3 Someone to watch over the body .................................................................. 3 The timing of the funeral ............................................................................... 3 The casket and dressing the deceased for burial .......................................... -

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities by Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’S Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities By Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’s Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative A note on the content below: We acknowledge that this document invokes heavily gendered language due to the prevailing historic male voices in Jewish rabbinic and biblical perspectives, and the fact that Hebrew (the language in which these laws originated) is a gendered language. We also recognize some of these perspectives might be in contradiction with one another and with some of NCJW’s approaches to the issues of reproductive health, rights, and justice. Background Family planning has been discussed in Judaism for several thousand years. From the earliest of the ‘sages’ until today, a range of opinions has existed — opinions which can be in tension with one another and are constantly evolving. Historically these discussions have assumed that sexual intimacy happens within the framework of heterosexual marriage. A few fundamental Jewish tenets underlie any discussion of Jewish views on reproductive realities. • Protecting an existing life is paramount, even when it means a Jew must violate the most sacred laws.1 • Judaism is decidedly ‘pro-natalist,’ and strongly encourages having children. The duty of procreation is based on one of the earliest and often repeated obligations of the Torah, ‘pru u’rvu’, 2 to be ‘fruitful and multiply.’ This fundamental obligation in the Jewish tradition is technically considered only to apply to males. Of course, Jewish attitudes toward procreation have not been shaped by Jewish law alone, but have been influenced by the historic communal trauma (such as the Holocaust) and the subsequent yearning of some Jews to rebuild community through Jewish population growth. -

Reflecting on When the Arukh Hashulhan on Orach Chaim Was Actually Written,There Is No Bracha on an Eclipse,A Note Regarding

Reflecting on When the Arukh haShulhan on Orach Chaim was Actually Written Reflecting on When the Arukh haShulhan on Orach Chaim was Actually Written: Citations of the Mishnah Berurah in the Arukh haShulhan Michael J. Broyde & Shlomo C. Pill Rabbi Michael Broyde is a Professor of Law at Emory University School of Law and the Projects Director at the Emory University Center for the Study of Law and Religion. Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Pill is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Jewish, Islamic, and American Law and Religion at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology and a Senior Fellow at the Emory University Center for the Study of Law and Religion. They are writing a work titled “Setting the Table: An Introduction to the Jurisprudence of Rabbi Yechiel Mikhel Epstein’s Arukh Hashulchan” (Academic Studies Press, forthcoming 2020). We post this now to note our celebration of the publication of תערוך לפני שלחן: חייו, זמנו ומפעלו של הרי”מ עפשטיין בעל ערוך Set a Table Before Me:The Life, Time, and Work of“) השלחן Rabbi Yehiel Mikhel Epstein, Author of the Arukh HaShulchan” .הי”ד ,see here) (Maggid Press, 2019), by Rabbi Eitam Henkin) Like many others, we were deeply saddened by his and his wife Naamah’s murder on October 1, 2015. We draw some small comfort in seeing that the fruits of his labors still are appearing. in his recently published הי”ד According to Rabbi Eitam Henkin book on the life and works of Rabbi Yechiel Mikhel Epstein, the first volume of the Arukh Hashulchan on Orach Chaim covering chapters 1-241 was published in 1903; the second volume addressing chapters 242-428 was published in 1907; and the third volume covering chapters 429-697 was published right after Rabbi Epstein’s death in 1909.[1] Others confirm these publication dates.[2] The Mishnah Berurah, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan’s commentary on the Orach Chaim section of the Shulchan Arukh was published in six parts, with each appearing at different times over twenty- three-year period. -

Torah Weekly

ב ס ״ ד Torah All the Mitzvos in Ki Teitzei concludes with the material world, it is confronted obligation to remember “what by challenges that may require Weekly Parshat Ki Teitzei Amalek did to you on the road, it to engage in battle. Seventy-four of the Torah’s on your way out of Egypt. For there are two aspects to August 15-21 2021 613 commandments (mitzvot) material existence. Our world 7 Elul – 13 Elul, 5781 are in the Parshah of Ki Teitzei. was created because G-d Torah Reading: These include the laws of the “desired a dwelling in the lower Ki Teitzei: Deuteronomy 21:10 - beautiful captive, the War and Peace: Will a worlds,” i.e., the physical 26:19 inheritance rights of the Haftarah: Dove Grow Claws? universe can serve as a dwelling Isaiah 54:1-54:10 firstborn, the wayward and for G-d, a place where His rebellious son, burial and Every day, we conclude essence is revealed. But as the dignity of the dead, returning a the Shemoneh Esreh prayers by term “lower worlds” implies, PARSHAT Ki Teitzei praising G-d “who blesses His lost object, sending away the G-d’s existence is not readily We have Jewish mother bird before taking her people Israel with peace.” And apparent in our environment. when describing the Calendars. If you young, the duty to erect a safety On the contrary, the material would like one, fence around the roof of one’s blessings G-d will bestow upon nature of the world appears to please send us a home, and the various forms of us if we follow His will, our preclude holiness. -

Potential Risk and Protective Factors for Eating Disorders in Haredi (Ultra‑Orthodox) Jewish Women

Journal of Religion and Health (2019) 58:2161–2174 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00854-2 PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLORATION Potential Risk and Protective Factors for Eating Disorders in Haredi (ultra‑Orthodox) Jewish Women Rachel Bachner‑Melman1,2 · Ada H. Zohar1 Published online: 7 June 2019 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Little is known scientifcally about eating disorders (EDs) in the Haredi (Jewish ultra-Orthodox) community. This paper aims to describe Haredi culture, review available peer-reviewed research on EDs in the Haredi community and discuss pos- sible risk and protective factors for these disorders in a culturally informed way. A literature search for 2009–2019 yielded 180 references of which only nine were stud- ies on ED in the Haredi community. We describe these and use them as a basis for discussion of possible risk and protective factors for ED in Haredi women. Risk fac- tors may include the centrality of food, poverty, rigid dress codes, the importance of thinness for dating and marriage, high demands from women, selfessness and early marriage and high expectations from women. Protective factors may include faith, Jewish laws governing eating and food that encourage gratitude and mindful eat- ing, and body covering as part of modesty laws that discourage objectifcation. Ways of overcoming the current barriers to research in the Haredi community should be sought to advance ED prevention and treatment in this population. Keywords Eating disorders · ultra-Orthodox · Haredi · Risk and protective factors · Body image Introduction Eating disorders (EDs) are characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating-related behavior that leads to altered consumption of food and the impairment of physical health or psychosocial functioning (APA 2013). -

Pandemic Passover 2.0 Answer to This Question

Food for homeless – page 2 Challah for survivors – page 3 Mikvah Shoshana never closed – page 8 Moving Rabbis – page 10 March 17, 2021 / Nisan 4, 5781 Volume 56, Issue 7 See Marking one year Passover of pandemic life Events March 16, 2020, marks the day that our schools and buildings closed last year, and our lives were and drastically changed by the reality of COVID-19 reaching Oregon. As Resources the soundtrack of the musical “Rent” put it: ~ pages Congregation Beth Israel clergy meet via Zoom using “525,600 minutes, how 6-7 CBI Passover Zoom backgrounds, a collection of which do you measure a year?” can be downloaded at bethisrael-pdx.org/passover. Living according to the Jewish calendar provides us with one Pandemic Passover 2.0 answer to this question. BY DEBORAH MOON who live far away. We measure our year by Passover will be the first major Congregation Shaarie Torah Exec- completing the full cycle Jewish holiday that will be celebrated utive Director Jemi Kostiner Mansfield of holidays and Jewish for the second time under pandemic noticed the same advantage: “Families rituals. Time and our restrictions. and friends from out of town can come need for our community Since Pesach is traditionally home- together on a virtual platform, people and these rituals haven’t stopped in this year, even based, it is perhaps the easiest Jewish who normally wouldn’t be around the though so many of our usual ways of marking these holiday to adapt to our new landscape. seder table.” holy moments have been interrupted. -

The Mysterious Wait Rfr Reporting

w ww VOL. f / NO. 1 CHESHVAN 5772 / NOVEMBER 2011 s xc THEDaf a K ashrus A MONTHLYH NEWSLETTER FOR TH E O U RABBINIC FIELD REPRESENTATIVE DAF NOTES to wine in comparison to his father because “my father waited 24 hours and I (merely) The first part of the article below originally appeared in the Kashrus Kaleidoscope section of Hamodia wait between one meal and the next” (eating Magazine’s 27 Teves, 5767 – January 17, 2007 issue and was entitled “The Three Hour Wait”. It is reprinted with permission at this time because of its connection to the recently learned Daf Yomi in Chulin 105 and meat in the first meal and dairy in the next). because of the newly added Part 2. The article has been renamed The Mysterious Wait with the original The question is, how long is the interval first section discussing the source for waiting three hours between meat and dairy. The newly added second between one meal and another? section discusses the sources for waiting six hours or part of the sixth hour. Some have suggested that those who wait three hours may understand Mar Ukva to be THE MYSTERIOUS WAIT referring to the interval between breakfast and lunch (a short, three-hour period) rather An Analysis of Various Minhagim Concerning Waiting than between lunch and dinner (a longer period). This explanation, however, presents Between Meat and Dairy a difficulty. Tosfos in Chulin 105A tells us that in Mar Ukva’s time only two meals RABBI YOSEF GROSSMAN were eaten daily. Presumably, when Mar Senior Educational Rabbinic Coordinator; Editor - The Daf HaKashrus Ukva stated that he waited between eating meat and eating dairy just the normal inter- val between meals, he was referring to the PART 1: THE THREE-HOUR WAIT The source for this minhag is shrouded in two daily meals that people ate in his time.