Population Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NETWORK NEWS Vol

Dec/Jan-Mar. 2018 NETWORK NEWS Vol. 35 - No. 4 Quarterly resource publication for single mothers Call or email to be added to News mailing list: 262-251-7333 [email protected] New HOPE Network director From Lisa Lopacinski, HOPE Network board president: We’d like to welcome Martha Collins, our new executive director! We were so pleased to find a candidate of her caliber to lead HOPE Network. Rebuild. Reshape. Refocus. Martha Collins is passionate about work with meaning. She brings to the job a passion for serving individuals, believing all people have the right to live with dignity. Martha was a raised by a single mother and is a long-time resident of the City of Milwaukee. She is the proud single mother of two boys, Sean (16) and Seth (11). Martha grew up in the inner city of Milwaukee, which shaped her personal values and beliefs. Her life experiences created a strong desire within her to be part of something bigger than herself. Raised by a par- ent who was not only hardworking but deeply involved in the com- munity, Martha learned firsthand the impact and rewarding experi- ence of giving back, and affecting change. She received a bachelor’s de- gree in management from Cardinal Stritch University, and is working to complete her master’s degree in nonprofit management and lead- ership. She has previous execu- tive leadership experience, which Help support programs for HOPE Network families during our expanded her skills in program annual campaign (see p. 4 for program successes). The mothers development and community en- and children are counting on your generosity! gagement. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

AGMA Decisions Agreed 24 November 2017 FINAL, Item 3F PDF

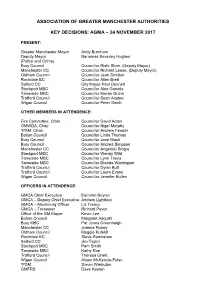

ASSOCIATION OF GREATER MANCHESTER AUTHORITIES KEY DECISIONS: AGMA – 24 NOVEMBER 2017 PRESENT: Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Deputy Mayor Baroness Beverley Hughes (Police and Crime) Bury Council Councillor Rishi Shori, (Deputy Mayor) Manchester CC Councillor Richard Leese, (Deputy Mayor) Oldham Council Councillor Jean Stretton Rochdale BC Councillor Allen Brett Salford CC City Mayor Paul Dennett Stockport MBC Councillor Alex Ganotis Tameside MBC Councillor Kieran Quinn Trafford Council Councillor Sean Anstee Wigan Council Councillor Peter Smith OTHER MEMBERS IN ATTENDENCE: Fire Committee, Chair Councillor David Acton GMWDA, Chair Councillor Nigel Murphy TfGM, Chair, Councillor Andrew Fender Bolton Council Councillor Linda Thomas Bury Council Councillor Jane Black Bury Council Councillor Andrea Simpson Manchester CC Councillor Angelicki Stogia Stockport MBC Councillor Wendy Wild Tameside MBC Councillor Lynn Travis Tameside MBC Councillor Brenda Warrington Trafford Council Councillor Dylan Butt Trafford Council Councillor Laura Evans Wigan Council Councillor Jennifer Bullen OFFICERS IN ATTENDENCE: GMCA Chief Executive Eamonn Boylan GMCA – Deputy Chief Executive Andrew Lightfoot GMCA – Monitoring Officer Liz Treacy GMCA – Treasurer Richard Paver Office of the GM Mayor Kevin Lee Bolton Council Margaret Asquith Bury MBC Pat Jones Greenhalgh Manchester CC Joanne Roney Oldham Council Maggie Kufeldt Rochdale BC Steve Rumbelow Salford CC Jim Taylor Stockport MBC Pam Smith Tameside MBC Kathy Roe Trafford Council Theresa Grant Wigan Council Alison McKenzie-Folan TfGM Simon Warbuton GMFRS Dave Keelan Manchester Growth Co Mark Hughes GMCA Julie Connor GMCA Lindsay Dunn GMCA Simon Nokes GMCA Emma Stonier GMCA Sylvia Welsh APOLOGIES: Bolton Council Councillor Cliff Morris Oldham Council Carolyn Wilkins Rochdale BC Councillor Richard Farnell Tameside MBC Steven Pleasant Wigan Council Donna Hall GMP Ian Hopkins GMHSC Partnership Jon Rouse TfGM Jon Lamonte Agenda Item No. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Big Bang – Shout out to the World!

Big Bang – Shout Out To The World! (English Translation) [2009] Shout out to the World: TOP “I came here because of that string of hope. Where do I stand now? I ask myself this but even I don’t have a specific answer yet. During the process where I search for my other self, all my worries will fade away because I must find the person who will lend his shoulders to me.” ~TOP Name: Choi Seung-hyun Date of Birth: November 4, 1987 Skills: Rap, Writing lyrics, Beatbox *Starred in the KBS Drama, ‘I am Sam’ The power to awaken a soul, sometimes it takes pain to be re-born. [~ Pt.One~] -I once wanted to be a lyric poet that composed and recited verses.- I became mesmerized with ‘Hip-Hop’ music when I was in Grade 5. I went crazy for this type of music because I listened to it all day and carefully noted all the rap lyrics. If we have to talk about Hip-Hop music, I have to briefly talk about the roots of American Hip-Hop. When I first started listening to Hip-Hop, it was divided up into East Coast and West Coast in America. Wu Tang Clan and Notorius B.I.G. represented the East Coast (New York) scene and they focused largely on the rap and the lyrics, while representing the West Coast (LA) was 2Pac who focused more on the melody. Although at that time in Korea and from my memory, more people listened to West Coast hip hop but I was more into the East Coast style. -

Let's Not Go Back to 70S Primary Education Wikio

This site uses cookies to help deliver services. By using this site, you agree to the use of cookies. Learn more Got it Conor's Commentary A blog about politics, education, Ireland, culture and travel. I am Conor Ryan, Dublin-born former adviser to Tony Blair and David Blunkett on education. Views expressed on this blog are written in a personal capacity. Friday, 20 February 2009 SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE UPDATES Let's not go back to 70s primary education Wikio Despite the Today programme's insistence on the term, "independent" is certainly not an apt Contact me description of today's report from the self-styled 'largest' review of primary education in 40 years. It You can email me here. is another deeply ideological strike against standards and effective teaching of the 3Rs in our primary schools. Many of its contributors oppose the very idea of school 'standards' and have an ideological opposition to external testing. They have been permanent critics of the changes of recent decades. And it is only in that light that the review's conclusions can be understood. Of course, there is no conflict between teaching literacy and numeracy, and the other subjects within the primary curriculum. And the best schools do indeed show how doing them all well provides a good and rounded education. Presenting this as the point of difference is a diversionary Aunt Sally. However, there is a very real conflict between recognising the need to single literacy and numeracy out for extra time over the other subjects as with the dedicated literacy and numeracy lessons, and making them just another aspect of primary schooling that pupils may or may not pick up along the way. -

Big Bang 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour in Seoul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Bang 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop / Stage & Screen Album: 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul Country: South Korea Released: 2013 Style: Dance-pop, Pop Rap, K-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1304 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1891 mb WMA version RAR size: 1730 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 540 Other Formats: DTS MP4 AAC VOC MOD AIFF AA Tracklist Disc 01 | 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul 1 Tonight 2 Hands Up 3 Fantastic Baby 4 How Gee 5 Stupid Liar 6 High High 7 Strong Baby + 어쩌라고 (What Can I Do) 8 가라가라 고 (Gara Gara Go) 9 Cafe 10 Bad Boy 11 Blue 12 재미없어 (Ain't No Fun) 13 사랑먼지 (Love Dust) 14 Love Song 15 나만 바라봐 (Only Look At Me) + Wedding Dress + Where U At 16 날개 (Wings) 17 하루하루 (Haru Haru) 18 거짓말 (Lies) 19 마지막 인사 (Last Farewell) 20 붉은 노을 (Sunset Glow)(Encore) 21 천국 (Heaven)(Encore) 22 Bad Boy (Double Encore) 23 Fantastic Baby (Double Encore) Disc 02 | Special Features 1 Making Film Multi Angle - Bad Boy (Encore) G-Dragon / T.O.P / Taeyang / Daesung / 2 Seungri Companies, etc. Marketed By – KBS Media Inc. Distributed By – KBS Media Inc. Notes Live DVD footage from BIGBANG's 2012 Alive World Tour Concert at the Olympic Gymnastics Stadium in Seoul on March 2-4, 2012. - 2 DVD - Photobook - First press comes with YG Family Card - Poster Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8803581194524 Other: 2013-KDVD0002 Related Music albums to 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul by Big Bang Big Bang - Bigbang Best Collection (Korea Edition) YG Family - YG Family 2014 World Tour: Power (Concert In Seoul Live CD) Fairport Convention - Encore Encore Various - The Swing Era: Encore! Fairport Convention - Farewell, Farewell Big Bang - 2015 Bigbang World Tour [Made] In Seoul DVD The Platters - More Encore Of Golden Hits Big Bang - Special Edition. -

Labour Warns Over Relaxing Sunday Trading Laws Churches Help Tackle

Labour warns over relaxing Sunday trading laws Shadow Business Secretary, Chuka Umunna, urges government to Keep Sundays Special Labour MP Chuka Umunna, pictured right, has attacked the government after senior Conservatives openly suggested that Sunday trading hours should be permanently extended. A temporary extension to Sunday trading hours in England and Wales was introduced by the Government for the duration of the Olympic and Paralympic games earlier this year. However, No 10 has confirmed that ministers are looking at making the change permanent. Eric Pickles, the Communities Secretary, said that an extension should be “looked at.” the rights of people of faith, and to maintain at least Speaking to Churches Update, Chuka said: “Any some distinctiveness for Sunday.” extension to Sunday trading hours on a permanent basis will break up the consensus that was carefully Chuka’s comments received support from Justin King, put together after proper consultation over a long Chief Executive of Sainsbury’s who warned a period of time of businesses, unions, churches and permanent extension to Sunday trading hours was other organisations.” Recognising the importance of “not a magic answer to economic regeneration.” King Sundays to families and churches across the country, was writing in a letter to the Sunday Telegraph, in he said: “It will also mean the end of Sundays being which the Church of England and the Union of Shop, special and put pressure on families with 24 hour Distributive and Allied Workers and the Association of working across all of the retail sector seven days a Convenience Stores also expressed concern about the week. -

Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron by Andrew Blick and George Jones

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2014/03/12/book-review-at-powers-elbow-aides-to-the-prime-minister-from-robert-walpole- to-david-cameron/ Book Review: At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron by Andrew Blick and George Jones Special Advisers and prime-ministerial aides have come to prominence increasingly over the last decade, with operatives like Alastair Campbell and Andy Coulson frequently making front-page news. But little is generally known about the role itself, what it entails, and how it has developed down the years. Catherine Haddon, in reviewing this new offering from Andrew Blick and George Jones, finds their history of the role enlightening and impressive in its breadth and scope. At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron. Andrew Blick and George Jones. Biteback Publishing. September 2013. Find this book: ‘The office of Prime Minister is occupied by one individual but the exercise of the role has always been a group activity’. With this theme at the heart, Andrew Blick and George Jones’ latest book moves on from their previous study of prime ministers to look at the advisers that surround them. Blick and Jones take us all the way back to Robert Walpole to examine how the support of aides and the reaction to them helped define not only the concept of permanent Civil Service but also the very role of Prime Minister itself. What Blick and Jones’ book demonstrates is that the UK premiership has not been a static organisation – it has adapted to the style and approach of the individuals that held the post. -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

Electronic Version

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Wolverhampton Intellectual Repository and E-theses Sandie Sandbrook Love or Protection? Defining and measuring maternal-fetal attachment from the woman’s perspective. Volume One Sandra Sandbrook BA (Joint Hons.), RN, RM, ADM, MTD, Cert. Ed (FE) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 The right of Sandra Patricia Sandbrook to be identified as the author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature: …………………………………………………… Date: ………………………………………………………… 1 Sandie Sandbrook Abstract Existing commonly used maternal-fetal attachment instruments have not been thoroughly tested for reliability and validity; criticism can be levelled for a variety of problems ranging from lack of reliability due to an inadequate underpinning framework to facilitate objective interpretation to limited generalizability due to the sample. The aim of this study is to acknowledge the centrality of the mother, to use the experiences of pregnant women to generate a definition of maternal- fetal attachment and ultimately create a tool that will act as a reliable, valid and simple measurement. A mixed method framework utilising a sequential exploratory strategy has allowed qualitative exploration of the phenomenon under investigation followed by quantitative testing of the emerging theory on a much larger and different sample. Phase 1 involved face to face open structured interviews on an opportunity sample of 10 (5 primigravid; 5 multiparous) women in the final trimester of pregnancy followed by 3 focus groups targeting specific groups – primigravid women (6 participants); multiparous women (7 participants) and teenagers (4 participants). -

Economy & Autonomy Blairfare: , Third-Way Disability and Dependency in Britain Introduction in This Paper We Intend to Explo

Economy & Autonomy Blairfare: , Third-Way Disability and Dependency in Britain Jennifer Harris University of Central Lancashire, UK BobSapey Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK John Stewart Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK Introduction In this paper we intend to explore the social policy changes in relation to disabled people which are taking place in the United Kingdom, particularly since the election of the Labour government on May 1, 1997. We intend to first examine the key differences between this govern- ment and previous administrations and then to describe the policy changes which have occurred. We shall describe certain historical aspects of British social policy which are relevant to our analysis, a description that itself will involve an evaluation of the power structures that are emerging. The term which has been commonly used to describe this government's approach to economic and social policy is the "third way" and, while we acknowledge the value of this term in that it implies an alternative to either a collectivist or anti-collectivist approach to welfare (George and Wilding 1976), we have chosen to describe the policies we are examining as "Blairfare." This term, a combination of Prime Minister Tony Blair's last name and welfare, is intended to signify the rather personal character of "the third way" in Britain. Globalisation and the Nation-State For the past couple of years, the United Kingdom has had a Labour government but, unlike the experience of previous Labour and Conservative administrations, under the leadership of Prime Minister Blair we have been witnessing one of the greatest constitutional shake-ups this century.