Sequential Rhetoric: Teaching Comics As Visual Rhetoric Robert Dennis Watkins Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

A Visual-Textual Analysis of Sarah Glidden's

BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial FulfillMent of the RequireMents for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by TYNAN STEWART Dr. Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have exaMined the thesis entitleD BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM presented by Tynan Stewart, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. —————————————————————————— Dr. Berkley Hudson —————————————————————————— Dr. Cristina Mislán —————————————————————————— Dr. Ryan Thomas —————————————————————————— Dr. Kristin Schwain DEDICATION For my parents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My naMe is at the top of this thesis, but only because of the goodwill and generosity of many, many others. Some of those naMed here never saw a word of my research but were still vital to My broader journalistic education. My first thank you goes to my chair, Berkley Hudson, for his exceptional patience and gracious wisdom over the past year. Next, I extend an enormous thanks to my comMittee meMbers, Cristina Mislán, Kristin Schwain, and Ryan Thomas, for their insights and their tiMe. This thesis would be so much less without My comMittee’s efforts on my behalf. TiM Vos also deserves recognition here for helping Me narrow my initial aMbitions and set the direction this study would eventually take. The Missourian newsroom has been an all-consuming presence in my life for the past two and a half years. -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

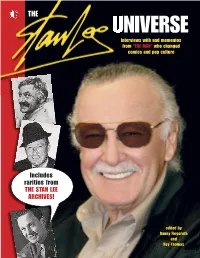

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Customer Order Form

#355 | APR18 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:51:03 PM You'll for PREVIEWS!PREVIEWS! STARTING THIS MONTH Toys & Merchandise sections start with the Back Cover! Page M-1 Dynamite Entertainment added to our Premier Comics! Page 251 BOOM! Studios added to our Premier Comics! Page 279 New Manga section! Page 471 Updated Look & Design! Apr18 Previews Flip Ad.indd 1 3/8/2018 9:55:59 AM BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SWORD SLAYER SEASON 12: DAUGHTER #1 THE RECKONING #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE MAN OF JUSTICE LEAGUE #1 THE LEAGUE OF STEEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EXTRAORDINARY DC ENTERTAINMENT GENTLEMEN: THE TEMPEST #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE MAGIC ORDER #1 IMAGE COMICS THE WEATHERMAN #1 IMAGE COMICS CHARLIE’S ANT-MAN & ANGELS #1 BY NIGHT #1 THE WASP #1 DYNAMITE BOOM! STUDIOS MARVEL COMICS ENTERTAINMENT Apr18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:39:16 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT InSexts Year One HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Lost City Explorers #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Carson of Venus: Fear on Four Worlds #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie’s Super Teens vs. Crusaders #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Solo: A Star Wars Story: The Official Guide HC l DK PUBLISHING CO The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide Volume 48 SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Mae Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE 1 A Tale of a Thousand and One Nights: Hasib & The Queen of Serpents HC l NBM Shadow Roads #1 l ONI PRESS INC. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Digital Comics: Panel Structure in a Digital Environment

Digital Comics: Panel Structure in a Digital Environment A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Nathaniel Shaw in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Digital Media May 2011 © Copyright 2011 Nathaniel Shaw. All Rights Reserved i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Troy Finamore, for all of the constructive criticism and support throughout the process of this thesis project. Without his suggestions and technical help the project would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the committee, Matt Kaufhold and Jervis Thompson, for their contributions, comments, and suggestions. If Matt hadn’t told me to make sure to have a beginning, middle, and end to my story I wouldn’t have thought to do the opposite. Special recognition goes to my sister, Nyssa Shaw, for her help when I was struggling with the story. Additionally, I would like to thank my fellow graduate students Dan Bodenstein, Bob Piscopo, Simon Littlejohn, and Greg Ruane for the support and sense of community. This thesis and Drexel Digital Media wouldn’t be the same without them. Thanks also goes to past Drexel students Evan Boucher, Dave Lally, Nick Avallone, Christian Hahn, Jessie Amadio, Justin Wilcott, and Tom Bergamini for their help throughout my education here at Drexel. I learned so much from each of them. Finally, I would like to thank the Drexel Digital Media faculty that helped me along the way. Dave Mauriello for his enthusiasm for teaching and dedication to the Digital Media program. Ted Artz for his interest in my thesis and creative input on other projects. -

Etherology, Or, the Philosophy of Mesmerism

TUFTS COLLEGE Tufts College Library « PHRENOLOG1.0AL BUST. See Page 164. • E THEE 0 LOG Y; OR, THE PHILOSOPHY OF MESMERISM . AND PHRENOLOGY: INCLUDING A NEW PHILOSOPHY OF SLEEP AND OF CONSCIOUSNESS, WITH A REVIEW OF THE PRETENSIONS OF NEUROLOGY AND PHRENO-MAGNETISM BY J. STANLEY GRIMES, COUNSELLOR AT LAW, FORMERLY PRESIDENT OF THE WESTERN PHRENOLOGICAL SOCIETY, PROFESSOR OF MEDICAL JURISPRUDENCE IN THE CASTLETON MEDICAL COLLEGE AND AUTHOR OF 4 A NEW SYSTEM OF PHRENOLOGY.' All the known phenomena of the universe may he referred to three general princi- ples, viz.: Matter, Motion, and Consciousness.—p. 17. NEW YORK: SAXTON AND MILES, NO. 205 BROADWAY PHILADELPHIA :-J AMES M. CAMPBELL. BOSTON I SAXTON, PEIRCE & CO. 1845. year by Entered according to Act of Congress, in the 1845, J. STANLEY GRIMES, the Southern District In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of of New York. 1 i m CONTENTS. SECTION I. page. SYNOFSIS OF ETHEROLOGY . 17 SECTION II. HISTORY OF ETHERIUM ..... 39 Ignorance of the Ancients concerning the causes of Ethe- rean Phenomena — Witchcraft — Divination — Magic — Discoveries which led to a Scientific Knowledge of Ethe- ropathy—Van Helmot—Mesmer—His Career—D'Eslon —Adverse Report of the French Commissioners—Foissac and the Academy of Medicine—Their favorable report —Gall—La Place. SECTION III. NATURE OF ETHERIUM ..... 75 Theory of Light—Of Heat—Of Electricity—Of Magnetism— Of Gravitation—Newton's Conjecture—Rev. Mr. Town- shend on the Mesmeric Medium—Sunderland's Notions —Animal Electricity—Experiments of Crosse—Electric Fishes. SECTION IV. OXYGEN ........ 127 SECTION V. PHILOSOPHY OF SLEEP 130 Liebig's Error.