Informal Workers in Bangkok, Thailand: Scan of Four Occupational Sectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ass Plan in T Essm Nning Thaila Ent of , Poli Nd F Disa Cies a Aster M And

Assessment of Disaster Management Planning, Policies and Responses in Thailand Prepared by Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC) Conducted by HelpAge International and AADMER Partnership Group (APG) March 2013 Acknowledgements HelpAge International as the Country Lead of the AADMER Partnership Group (APG) in Thailand would like to thank the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (DDPM), ASEAN Disaster Preparedness Center (ACPD) and the regional APG management team for their support in conducting this study and preparing the report. We would also like to thank key informants who provided relevant information and their insights on disaster management in Thailand, which has enriched the study results. The document is available at www.helpage.org/resources/publications and http://www.aadmerpartnership.org/resources/publications. APG is a consortium of international NGOs that partners with the ASEAN, national disaster management offices and other stakeholders for the implementation of AADMER. APG is comprised of ChildFund, HelpAge, Mercy Malaysia, Oxfam, Plan International, Save the Children, World Vision. It aims to facilitate the working together of national and ASEAN disaster risk reduction and disaster management bodies and civil society towards reducing risks for vulnerable groups. List of Acronyms AA Action Aid AADMER ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response ACDM ASEAN Committee on Disaster Management ADDM ASEAN Day for Disaster Management ADPC Asian Disaster Preparedness Center AEC ASEAN Economic Community -

Review of Urban Transport Policy and Its Impact in Bangkok

Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.6, 2007 REVIEW OF URBAN TRANSPORT POLICY AND ITS IMPACT IN BANGKOK Shinya HANAOKA Associate Professor Department of International Development Engineering Tokyo Institute of Technology 2-12-1-I4-12 O-okayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 152-8550, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper reviews transport policy, implementation and its impact in Bangkok. Bangkok has not done any special measures in its transportation system. Many ambitious policies have been planned like the exclusive bus lane and the automatic location system for buses. However, they have only reached the experimental level and have not reached full implementation because of financial constraints and political conflicts. Only the ring road, expressway, overpass, underpass, truck ban, BTS and MRT have been successfully implemented. Key Words: Transport Policy, Bangkok, Historical Review 1. INTRODUCTION Transport system in Bangkok has been relying on a poorly planned road network. Roads are significantly insufficient relative to the city size and population. Existing access roads or sois (dead-end streets) are generally unplanned and narrow with poor connections to the road hierarchy. With these road conditions, Bangkok has established a worldwide reputation for traffic congestion (PADECO, 2000). Traffic congestion in Bangkok results to wasteful burning of fuel and contributes heavily to air pollution, both of which are adversely affecting people’s health and climate change. The conditions have been even more worsening since the recovery of Thailand’s economy after financial crisis. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) reported that in 1995 bus transit accounted for 48 percent of total trips in Bangkok while personal cars accounted for only 27 percent (JICA, 1997). -

AW AR2014 Homepro English.Indd

Annual Report 2014 HomePro is the leading home improvement retailer in Thailand . We operate 71 stores nationwide, providing product range cover 40,000 items with complete services as One Stop Shopping to attain hightest customer satisfaction. Sales Net Profit No. of Total Asset New Stores New Relocation Contents 2 Message from Chairman 3 Message from Managing Director 14 Financial Information 15 General Information 20 Board of Directors and Management Profile 28 Nature of Business 33 Risk Factors 38 Shareholding Structure 39 Organizational Chart 40 Management 59 Corporate Governance 67 Sustainable Development Report 98 Internal Control 100 Dividend Policy 101 Related Transaction 103 Management Discussion and Analysis of Financial Status and Operaing Results 111 Audit Committee’s Report 113 Report of Board of Directors’ Responsibilities in the Financial Statement 114 Independent Auditor’s Report 115 Financial Statement Home Product Center Plc. 1 Message from the Chairman “Sustainable growth can be achieved together with the Company’s responsibility to stakeholders, by considering the impacts and benefits to stakeholders from our business operations, both in the short-term and long-term” In 2014, it appeared that Thailand’s economy The Company has realized that profitability and fluctuated a lot over the year. In the first half of sustainable growth can be achieved together with the year, the economy shrank due to political unrest the Company’s responsibility to stakeholders, by having an adverse effect on domestic consumers’ considering the impacts and benefits to stakeholders confidence, especially in the protest areas (i.e. from our business operations, both in short-term and Bangkok and its vicinity). -

An Urban Political Ecology of Bangkok's Awful Traffic Congestion

An urban political ecology of Bangkok's awful traffic congestion Danny Marks1 Dublin City University, Ireland Abstract Urban political ecology (UPE) can contribute important insights to examine traffic congestion, a significant social and environmental problem underexplored in UPE. Specifically, by attending to power relations, the production of urban space, and cultural practices, UPE can help explain why traffic congestions arises and persists but also creates inequalities in terms of environmental impacts and mobility. Based on qualitative research conducted in 2018, the article applies a UPE framework to Bangkok, Thailand, which has some of the world's worst congestion in one of the world's most unequal countries. The city's largely unplanned and uneven development has made congestion worse in a number of ways. Further, the neglect of public transport, particularly the bus system, and the highest priority given to cars has exacerbated congestion but also reflects class interests as well as unequal power relations. Governance shortcomings, including fragmentation, institutional inertia, corruption, and frequent changes in leadership, have also severely hindered state actors to address congestion. However, due to the poor's limited power, solutions to congestion, are post-political and shaped by elite interests. Analyses of congestion need to consider how socio-political relations, discourses, and a city's materiality shape outcomes. Key Words: urban transport governance, Bangkok traffic congestion, urban political ecology, Thailand political economy, Bangkok's bus system Résumé L'écologie politique urbaine (EPU) peut apporter des informations importantes pour examiner la congestion routière, un problème social et environnemental important sous-exploré dans l'EPU. Plus précisément, en s'occupant des relations de pouvoir, de la production d'espace urbain et des pratiques culturelles, l'EPU peut aider à expliquer pourquoi les embouteillages surviennent et persistent mais créent également des inégalités en termes d'impacts environnementaux et de mobilité. -

Table of Contents Page

Executive Summary Report Project to study the traveling navigation system with public transportation in Bangkok and vicinity areas Table of Contents Page Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Study, review the study results or the operational performance with relevant agencies both domestically and internationally, explore, and analyze the linkage of public transport networks via roads, rails and waterways that are serviced in Bangkok and vicinity areas ..................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Study, review the study results or the operational performance with relevant agencies both domestically and internationally, and explore the routes and public transport systems via roads, rails and waterways that are serviced in Bangkok and vicinity areas ....................................................... 3 1.2.2 Collect the route information, starting points, destinations, stations, stops, and information related to public transportation via roads, rails and waterways that provide service routes in Bangkok and vicinity areas. ...... 7 1.2.3 Analyze all public transport network connections and create map data showing public transport routes and modes based on the collected data supplementary for the development of public transport systems to be able to support the future urban expansion .............................................. 12 Design and development of database from the collection and analysis -

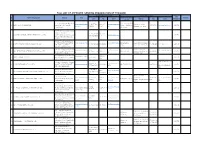

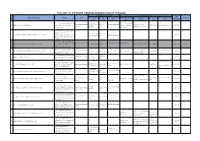

FULL LIST of APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION of THAILAND Approved Person in Charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Date No

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION OF THAILAND Approved Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan date No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in Remarks name TEL Email Address TEL Email (the date of Charge receipt) 10th ft. Social security., Ministry of Office of Labour Affair https://www.doe.go.th MR. KHATTIYA +662 245 [email protected] 3-14-6 kami - Osaki, 1 DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT Labour Mitr-Maitri Road, Din- in Japan (Mr.Saichon 03-5422-7014 [email protected] 2019/7/2 /overseas PANDECH 6708-9 om Shinagawa - ku Tokyo Daeng Bangkok Akanitvong) 259/333 2ND Floor Yangyuenwong Building, Sukhumvit 71 MR. PASSAPONG (66)-2-391- 2 J.J.S. BANGKOK DEVELOPMENT & MANPOWER CO., LTD. Road,Phrakhanongnua Sub-district, - [email protected] 2019/7/2 YANGYUENWONG 3499 Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Thailand No.7,1ST FLOOR, SOI NAKNIWAT 57, NAKNIWAT ROAD, LADPRAO www.linkproplacement. [email protected] Ms. Suwutjittra Tokyo, Adachi Ku, Higashi 3 LINKPRO INTERNATIONAL PLACEMENT CO., LTD. MR. Korn Sakajai 080-6113525 090-7945-2494 [email protected] 2019/7/2 SUB-DISTRICT, LADPRAO net om Nawilai Ayase 1-15-19-102 Room DISTRICT, BANGKOK 10230 293/1,Mu 15,Nang-Lae Sub-district, 247-0071 Tamagawa, www.ainmanpower.co [email protected] [email protected] 4 ASIA INTERNATIONAL NETWORK MANPOWER CO., LTD. Muang Chiangrai District, Chiangrai Ms. Mayuree Jina 0918599777 Mr. Shoichi Saho Kamakura City, Kanagawa 080-3449-1607 2019/7/2 m .th h Province 57100 Thailand Prefecture, Japan 163/1 Nuanchan Rd,Nuanchan Sub- www.vincplacement.co +662 735 5 VINC PLACEMENT CO., LTD. -

FULL LIST of APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION of THAILAND Approved Person in Charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Date No

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION OF THAILAND Approved Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan date No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in Remarks name TEL Email Address TEL Email (the date of Charge receipt) 10th ft. Social security., Ministry of Office of Labour Affair https://www.doe.go.th MR. KHATTIYA +662 245 [email protected] 3-14-6 kami - Osaki, 1 DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT Labour Mitr-Maitri Road, Din- in Japan (Mr.Saichon 03-5422-7014 [email protected] 2019/7/2 /overseas PANDECH 6708-9 om Shinagawa - ku Tokyo Daeng Bangkok Akanitvong) 259/333 2ND Floor Yangyuenwong Building, Sukhumvit 71 MR. PASSAPONG (66)-2-391- 2 J.J.S. BANGKOK DEVELOPMENT & MANPOWER CO., LTD. Road,Phrakhanongnua Sub-district, - [email protected] 2019/7/2 YANGYUENWONG 3499 Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Thailand No.7,1ST FLOOR, SOI NAKNIWAT 57, NAKNIWAT ROAD, LADPRAO www.linkproplacement. [email protected] Ms. Suwutjittra Tokyo, Adachi Ku, Ayase2- 3 LINKPRO INTERNATIONAL PLACEMENT CO., LTD. MR. Korn Sakajai 081-5703006 090-7945-2494 - 2019/7/2 Expired SUB-DISTRICT, LADPRAO net om Nawilai 29-3, Kaimudon, 2F Japan DISTRICT, BANGKOK 10230 293/1,Mu 15,Nang-Lae Sub-district, 247-0071 Tamagawa, www.ainmanpower.co [email protected] [email protected] 4 ASIA INTERNATIONAL NETWORK MANPOWER CO., LTD. Muang Chiangrai District, Chiangrai Ms. Mayuree Jina 0918599777 Mr. Shoichi Saho Kamakura City, Kanagawa 080-3449-1607 2019/7/2 m .th h Province 57100 Thailand Prefecture, Japan 163/1 Nuanchan Rd,Nuanchan Sub- www.vincplacement.co +662 735 5 VINC PLACEMENT CO., LTD. -

Improving Public Bus Service and Non-Motorised Transport in Bangkok

ASEAN - German Technical Cooperation | Energy Efficiency and Climate Change Mitigation in the Land Transport Sector Improving Public Bus Service and Non- Motorised Transport in Bangkok A Study for the Thailand Mobility NAMA October 2016 Disclaimer Findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this document are based on information gathered by GIZ and its consultants, partners and contributors. Acknowledgements GIZ does not, however, guarantee the accuracy We would like to thank Paul Williams, or completeness of information in this Dr. Kunchit Phiu-Nual, Stefan Bakker, document, and cannot be held responsible for Papondhanai Nanthachatchavankul, Tali Trigg any errors, omissions or losses which emerge and Farida Moawad for their valuable inputs from its use. and comments. Improving Public Bus Service and Non- Motorised Transport in Bangkok A Study for the Thailand Mobility NAMA Kerati Kijmanawat, Pat Karoonkornsakul (PSK Consultants Ltd.) The Project Context As presented to the ASEAN Land Transport The GIZ Programme on Cities, Environment Working group, TCC’s regional activities are in and Transport (CET) in ASEAN seeks to the area of fuel efficiency, strategy development, reduce emissions from transport and industry by green freight, and Nationally Appropriate providing co-benefits for local and global Mitigation Actions in the transport sector. At environmental protection. The CET Project the national level the project supports relevant ‘Energy Efficiency and Climate Change transport and environment government bodies Mitigation in the Land Transport Sector in the in the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia ASEAN region’ (Transport and Climate Change and Indonesia, for the development of national (TCC) www.TransportandClimateChange.org) action plans and improvement of policy aims in turn to develop strategies and action monitoring systems. -

Water Transportation in Bangkok: Past, Present, and the Future อดีต ปัจจุบัน และอนาคตของการคมนาคมขนส่งทางน้ำในกรุงเทพมหานคร

Research Articles on Urban Planning Water Transportation in Bangkok: Past, Present, and the Future อดีต ปัจจุบัน และอนาคตของการคมนาคมขนส่งทางน้ำในกรุงเทพมหานคร Moinul Hossain and Pawinee Iamtrakul, Ph.D. Water Transportation in Bangkok: Past, Present, and the Future Moinul Hossain and Pawinee Iamtrakul, Ph.D. 1 Journal of Architectural/Planning Research and Studies Volume 5. Issue 2. 2007 2 Faculty of Architecture and Planning, Thammasat University Water Transportation in Bangkok: Past, Present, and the Future อดีต ปัจจุบัน และอนาคตของการคมนาคมขนส่งทางน้ำในกรุงเทพมหานคร Moinul Hossain1 and Pawinee Iamtrakul, Ph.D.2 1 Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) 2 Faculty of Architecture and Planning, Thammasat University Abstract Once, Bangkok was known to the world as the “Venice of the East.” However, the role of water based transport has diminished gradually over the last few decades and has vastly been replaced by traditional land-based transportation system. Nowadays, most of the waterway networks have been paved over with roads and the existing water transport facilities along the Chao Phraya river and its canals in Bangkok. Moreover, the existing system lacks adequate accessibility, inter-modal linkages as well as safety. This research study intends to present an overview of this public transport system together with its role and characteristics. In addition, it also intends to recommend some measures to improve the transportation system along these canals in Bangkok and exhibits how the reincarnation of this mode of transport can leave -

FULL LIST of APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION of THAILAND Person in Charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Approved No

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION OF THAILAND Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Approved No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in date Remarks name TEL Email Address TEL Email Charge (the date of 10th ft. Social security., Ministry of Office of Labour Affair DEPARTMENT OF https://www.doe.go.th/ MR.KHATTIYA +662 245 [email protected] 3-14-6 kami - Osaki, 1 Labour Mitr-Maitri Road, Din-Daeng in Japan (Mr.Saichon 03-5422-7014 [email protected] 2019/7/2 EMPLOYMENT overseas PANDECH 6708-9 om Shinagawa - ku Tokyo Bangkok Akanitvong) 259/333 2ND Floor Yangyuenwong J.J.S. BANGKOK Building, Sukhumvit 71 MR.PASSAPONG 2 DEVELOPMENT & Road,Phrakhanongnua Sub-district, - (66)[email protected] 2019/7/2 YANGYUENWONG MANPOWER CO., LTD. Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Thailand No.7,1ST FLOOR, SOI NAKNIWAT LINKPRO INTERNATIONAL 57, NAKNIWAT ROAD, LADPRAO www.linkproplacement. [email protected] Tokyo, Adachi Ku, Ayase2- 3 MR.Korn Sakajai 081-5703006 Ms.Suwutjittra Nawilai 090-7945-2494 - 2019/7/2 Expired PLACEMENT CO.,LTD. SUB-DISTRICT, LADPRAO net om 29-3,Kaimudon,2F Japan DISTRICT, BANGKOK 10230 ASIA INTERNATIONAL 293/1,Mu 15,Nang-Lae Sub-district, 247-0071 Tamagawa, [email protected] 4 NETWORK MANPOWER Muang Chiangrai District, Chiangrai www.ainmanpower.com Ms.Mayuree Jina 0918599777 Mr.Shoichi Saho Kamakura City, Kanagawa 080-3449-1607 [email protected] 2019/7/2 .th CO.,LTD. Province 57100 Thailand Prefecture, Japan 163/1 Nuanchan Rd,Nuanchan Sub- www.vincplacement.co 5 VINC PLACEMENT CO.,LTD. -

Infected Areas As on 6 August 1987 — Zones Infectées Au 6 Août 1987

U kl\ Epidem Rec Nu 32-7 August 1987 - 238 - Releve eptdem ftebd Nu 32 - 7 août 1987 PARASITIC DISEASES MALADIES PARASITAIRES Prevention and control of intestinal parasitic infections Lutte contre les parasitoses intestinales New WHO publication1 Nouvelle publication de l’OM S1 This report outlines new approaches to the prevention and con Ce rapport décrit les nouvelles méthodes de lutte contre les parasitoses trol of intestinal parasitic infections made possible by the recent intestinales mises au point grâce à la découverte de médicaments efficaces discovery of safe and effective therapeutic drugs, the improvement et sans danger, à l’amélioration et à la simplification de certaines and simplification of diagnostic procedures, and advances in the méthodes de diagnostic et aux progrès réalisés en biologie des populations understanding of parasite population biology. Newly available parasitaires. A partir de données nouvelles sur l'impact économique et information on the economic and social impact of these infections social de ces infections, il montre qu’il est nécessaire et possible de les is used to illustrate the necessity, as well as the feasibility, of maîtriser. bringing these infections under control. In view of the staking variations in the biology of different La biologie des différents parasites intestinaux ainsi que la forme et la intestinal parasites and in the form and severity of the diseases gravité des maladies qu’ils provoquent varient énormément, aussi le they cause, the book opens with individual profiles for each of the rapport commence-t-il par dresser un profil des principales helminthiases main helminthic and protozoan infections of public health impor et protozooses qui revêtent une importance du point de vue de la santé tance. -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received Bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 9 Au 14 Mai 1980 C Cases — Cas

Wkty Epldem. Bec.: No. 20 -16 May 1980 — 150 — Relevé éptdém. hebd : N° 20 - 16 mal 1980 Kano State D elete — Supprimer: Bimi-Kudi : General Hospital Lagos State D elete — Supprimer: Marina: Port Health Office Niger State D elete — Supprimer: Mima: Health Office Bauchi State Insert — Insérer: Tafawa Belewa: Comprehensive Rural Health Centre Insert — Insérer: Borno State (title — titre) Gongola State Insert — Insérer: Garkida: General Hospital Kano State In se rt— Insérer: Bimi-Kudu: General Hospital Lagos State Insert — Insérer: Ikeja: Port Health Office Lagos: Port Health Office Niger State Insert — Insérer: Minna: Health Office Oyo State Insert — Insérer: Ibadan: Jericho Nursing Home Military Hospital Onireke Health Office The Polytechnic Health Centre State Health Office Epidemiological Unit University of Ibadan Health Services Ile-Ife: State Hospital University of Ife Health Centre Ilesha: Health Office Ogbomosho: Baptist Medical Centre Oshogbo : Health Office Oyo: Health Office DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications reçues du 9 au 14 mai 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres non encore disponibles D Deaths — Décès / Imported cases — Cas importés P t o n r Revised figures — Chifircs révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects CHOLERA — CHOLÉRA C D YELLOW FEVER — FIÈVRE JAUNE ZAMBIA — ZAMBIE 1-8.V Africa — Afrique Africa — Afrique / 4 0 C 0 C D \ 3r 0 CAMEROON. UNITED REP. OF 7-13JV MOZAMBIQUE 20-26J.V CAMEROUN, RÉP.-UNIE DU 5 2 2 Asia — Asie Cameroun Oriental 13-19.IV C D Diamaré Département N agaba....................... î 1 55 1 BURMA — BIRMANIE 27.1V-3.V Petté ...........................