The Architecture of the Ècole Des Beaux-Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montauban 1780 - Paris 1867

Jean-Auguste-Dominique INGRES (Montauban 1780 - Paris 1867) Portrait of Gaspard Bonnet Pencil. Laid down. Signed and dated Ingres Rome / 1812 at the lower right. 222 x 161 mm. (8 3/4 x 6 3/8 in.) Around 460 portrait drawings by Ingres are known today, most of which date from before 1824, when he left Italy and returned to Paris. His Roman portrait drawings can be divided into two distinct groups; commissioned, highly finished works for sale, and more casual studies of colleagues and fellow artists, which were usually presented as a gift to the sitter. He had a remarkable ability of vividly capturing, with a few strokes of a sharpened graphite pencil applied to smooth white or cream paper, the character and personality of a sitter. (Indeed, it has been noted that it is often possible to tell which of his portrait subjects the artist found particularly sympathetic or appealing.) For his drawn portraits, Ingres made use of specially prepared tablets made up of several sheets of paper wrapped around a cardboard centre, over which was stretched a sheet of fine white English paper. The smooth white paper on which he drew was therefore cushioned by the layers beneath, and, made taut by being stretched over the cardboard tablet, provided a resilient surface for the artist’s finely-executed pencil work. A splendid example of Ingres’s informal portraiture, the present sheet was given by the artist to the sitter. It remained completely unknown until its appearance in the 1913 exhibition David et ses élèves in Paris, where it was lent from the collection of the diplomat Comte Alfred-Louis Lebeuf de Montgermont (1841-1918) and identified as a portrait of ‘M. -

In This Issue in Toronto and Jewelry Deco Pavilion

F A L L 2 0 1 3 Major Art Deco Retrospective Opens in Paris at the Palais de Chaillot… page 11 The Carlu Gatsby’s Fashions Denver 1926 Pittsburgh IN THIS ISSUE in Toronto and Jewelry Deco Pavilion IN THIS ISSUE FALL 2013 FEATURE ARTICLES “Degenerate” Ceramics Revisited By Rolf Achilles . 7 Outside the Museum Doors By Linda Levendusky . 10. Prepare to be Dazzled: Major Art Deco Retrospective Opens in Paris . 11. Art Moderne in Toronto: The Carlu on the Tenth Anniversary of Its Restoration By Scott Weir . .14 Fashions and Jewels of the Jazz Age Sparkle in Gatsby Film By Annette Bochenek . .17 Denver Deco By David Wharton . 20 An Unlikely Art Deco Debut: The Pittsburgh Pavilion at the 1926 Philadelphia Sesquicentennial International Exposition By Dawn R. Reid . 24 A Look Inside… The Art Deco Poster . 27 The Architecture of Barry Byrne: Taking the Prairie School to Europe . 29 REGULAR FEATURES President’s Message . .3 CADS Recap . 4. Deco Preservation . .6 Deco Spotlight . .8 Fall 2013 1 Custom Fine Jewelry and Adaptation of Historic Designs A percentage of all sales will benefit CADS. Mention this ad! Best Friends Elevating Deco Diamonds & Gems Demilune Stacker CADS Member Karla Lewis, GG, AJP, (GIA) Zig Zag Deco By Appointment 29 East Madison, Chicago u [email protected] 312-269-9999 u Mobile: 312-953-1644 bestfriendsdiamonds.com Engagement Rings u Diamond Jewelry u South Sea Cultured Pearl Jewelry and Strands u Custom Designs 2 Chicago Art Deco Society Magazine CADS Board of Directors Joseph Loundy President Amy Keller Vice President PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Susanne Petersson Secretary Mary Miller Treasurer Ruth Dearborn Ann Marie Del Monico Steve Hickson Conrad Miczko Dear CADS Members, Kevin Palmer Since I last wrote to you in April, there have been several important personnel changes at CADS . -

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850 Gallery 15

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 - 5 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. At this point in Domenichino’s career he wanted more commissions for narrative scenes and knew he needed to demonstrate his skill in depicting human action. -

QUES in ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1

[email protected] - QUES IN ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1 Faculty: Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Reinhold Martin, Mabel O. Wilson Teaching Fellows: Oskar Arnorsson, Benedict Clouette, Eva Schreiner Thurs 11am-1pm Fall 2016 This two-semester introductory course is organized around selected questions and problems that have, over the course of the past two centuries, helped to define architecture’s modernity. The course treats the history of architectural modernity as a contested, geographically and culturally uncertain category, for which periodization is both necessary and contingent. The fall semester begins with the apotheosis of the European Enlightenment and the early phases of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. From there, it proceeds in a rough chronology through the “long” nineteenth century. Developments in Europe and North America are situated in relation to worldwide processes including trade, imperialism, nationalism, and industrialization. Sequentially, the course considers specific questions and problems that form around differences that are also connections, antitheses that are also interdependencies, and conflicts that are also alliances. The resulting tensions animated architectural discourse and practice throughout the period, and continue to shape our present. Each week, objects, ideas, and events will move in and out of the European and North American frame, with a strong emphasis on relational thinking and contextualization. This includes a historical, relational understanding of architecture itself. Although the Western tradition had recognized diverse building practices as “architecture” for some time, an understanding of architecture as an academic discipline and as a profession, which still prevails today, was only institutionalized in the European nineteenth century. -

From Watteau to David the Horvitz Collection

PRESS KIT From Watteau to David february 2017 THE HORVITZ COLLECTION 21 march - 9 july 2017 Tuesday-Sunday INFORMATION 10am – 6pm Late opening - Friday until 9 pm www.petitpalais.paris.fr François Boucher, Reclining Female Nude (detail), circa 1740. Red chalk. © The Horvitz Collection – Photo: M. Gould The exhibition is organised in partnership with the Horvitz Collection PRESS OFFICER Mathilde Beaujard [email protected] Tél : + 33 1 53 43 40 21 CONTENTS Press release p. 3 Guide to the exhibition p. 4 Scenography of the exhibition p. 8 Exhibition catalogue p. 9 Paris Musées, a network of Paris museums p. 10 About the Petit Palais p. 11 Practical information p. 12 Communication manager Mathilde Beaujard [email protected] Tel : +33 1 53 43 40 21 2 From Watteau to David, The Horvitz Collection - 21 march - 9 july 2017 PRESS RELEASE The Petit Palais is delighted to be presenting an anthology of some 200 18th-century French paintings, sculptures and drawings from the Horvitz Collection in Boston. The work of thirty years, this is the largest private collection of 18th-century French drawings outside France, and is home to such artists of the first rank as Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, Greuze and David. It also offers an overview of all the major artists of the period, ranging from Oudry to De Troy, from Natoire to Bouchardon and from Hubert Robert to Vincent – and all of them at their best. The exhibition offers the visitor an exhaustive panorama of French painting and drawing from the Regency to the Revolution, together with a small but impeccable selection of of sculptures, including pieces by Lemoyne, Pajou and Houdon. -

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 As a Masterpiece of Late Gothic Architecture

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 as a masterpiece of late Gothic architecture. The church’s reputation was strong enough of the time for it to be chosen as the location for a young Louis XIV to receive communion. Mozart also Church of Saint 2 Impasse Saint- chose the sanctuary as the location for his mother’s funeral. Among ** Unknown Eustace Eustache those baptised here as children were Richelieu, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, future Madame de Pompadour and Molière, who was also married here in the 17th century. Amazing façade. Mon-Fri (9.30am-7pm), Sat-Sun (9am-7pm) Japanese architect Tadao Ando has revealed his plans to convert Paris' Bourse de Commerce building into a museum that will host one of the world's largest contemporary art collections. Ando was commissioned to create the gallery within the heritage-listed building by French Bourse de Commerce ***** Tadao Ando businessman François Pinault, who will use the space to host his / Collection Pinault collection of contemporary artworks known as the Pinault Collection. A new 300-seat auditorium and foyer will be set beneath the main gallery. The entire cylinder will be encased by nine-metre-tall concrete walls and will span 30 metres in diameter. Opening soon The Jardin du Palais Royal is a perfect spot to sit, contemplate and picnic between boxed hedges, or shop in the trio of beautiful arcades that frame the garden: the Galerie de Valois (east), Galerie de Montpensier (west) and Galerie Beaujolais (north). However, it's the southern end of the complex, polka-dotted with sculptor Daniel Buren's Domaine National du ***** 8 Rue de Montpensier 260 black-and-white striped columns, that has become the garden's Palais-Royal signature feature. -

Architecture: the Museum As Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12

Architecture: The Museum as Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12 Program Outline & Volunteer Resource Package Single Visit Program Option : 2 HOURS Contents of Resource Package Contents Page Program Development & Description 1 Learning Objectives for Students & Preparation Guidelines 2 One Page Program Outline 3 Powerpoint Presentation Overview 4 - 24 Glossary – Architectural Terms 24 - 27 Multimedia Resource Lists (Potential Research Activities) 27 - 31 Field Journal Sample 32 - 34 Glossary – Descriptive Words Program Development This programme was conceived in conjunction with the MOA Renewal project which expanded the Museum galleries, storages and research areas. The excitement that developed during this process of planning for these expanded spaces created a renewed enthusiasm for the architecture of Arthur Erickson and the landscape architecture of Cornelia Oberlander. Over three years the programme was developed with the assistance of teacher specialists, Jane Kinegal, Cambie Secondary School and Russ Timothy Evans, Tupper Secondary School. This programme was developed under the direction of Jill Baird, Curator of Education & Public Programmes, with Danielle Mackenzie, Public Programs & Education Intern 2008/09, Jennifer Robinson, Public Programs & Education Intern 2009/10, Vivienne Tutlewski, Public Programs & Education Intern 2010/2011, Katherine Power, Public Programs & Education Workstudy 2010/11, and Maureen Richardson, Education Volunteer Associate, who were all were key contributors to the research, development and implementation of the programme. Program Description Architecture: The Museum as Muse, Grades 6 - 12 MOA is internationally recognized for its collection of world arts and culture, but it is also famous for its unique architectural setting. This program includes a hands-on phenomenological (sensory) activity, an interior and exterior exploration of the museum, a stunning visual presentation on international museum architecture, and a 30 minute drawing activity where students can begin to design their own museum. -

Subasta Octubre 2019

Subasta Octubre 2019 MITTWOCH 9 OKTOBER 2019 KL. 16:00 CEST (1 - 481) 1. LOMBARD SCHOOL. Gold reliquary medallion, late 16th 9. Jewellery set consisting of a brooch and earrings in gold, first Century - early 17th Century. half of the 19th Century. 18K gold, black enamel and central medallion depicting the Adoration of 14K gold, gilt metal and oval, round and square cut garnets, 1.80 cts the Shepherds on the front and the Flight to Egypt on the back, in approx. Brooch: 5.4x4.5 cm. Earrings: 4.3 cm. 20.5 gr. reverse-glass painting and églomisé. 4.8 x 3.8 cm. 31.8 gr. Schätzwert: 750 EUR Schätzwert: 550 EUR Endpreis: - Endpreis: 1.800 EUR 10. Catalan silver long earrings, 19th Century. 2. Two reliquary pendants, 17th-18th centuries. Silver, probably oval, cushion and pear cut topazes, 2.85 cts and rose One of them in the shape of Jerusalem Cross in silver and wood with cut diamonds, 0.25 cts approx. Original case included. 5.8 x 1.4 cm. mother of pearl inlays; and the other one as a medallion depicting Our 13.9 gr. Lady of Sorrows with the attributes of passion on the front and Saint Schätzwert: 300 EUR Margaret in an illuminated engraving on the back. 7.5x4.8 cm and 7x4.7 Endpreis: 650 EUR cm. 56.3 gr. Schätzwert: 550 EUR 11. Coral long earrings and bracelet, 19th Century. Endpreis: - 14K and 18K gold, coral beads, two flower-shaped coral beads, carved coral beads and coral cameo with the representation of a male bust. -

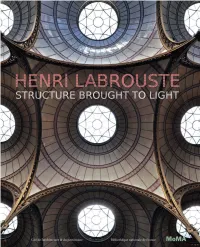

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light Is the Condensed Result of Several Years of Research, Goers Are Plunged

HENRI LABROUSTE STRUCTURE BROUGHT TO LIGHT With essays by Martin Bressani, Marc Grignon, Marie-Hélène de La Mure, Neil Levine, Bertrand Lemoine, Sigrid de Jong, David Van Zanten, and Gérard Uniack The Museum of Modern Art, New York In association with the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine et the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the special participation of the Académie d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. This exhibition, the first the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine has devoted to Since its foundation eighty years ago, MoMA’s Department of Architecture (today the a nineteenth-century architect, is part of a larger series of monographs dedicated Department of Architecture and Design) has shared the Museum’s linked missions of to renowned architects, from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau to Claude Parent and showcasing cutting-edge artistic work in all media and exploring the longer prehistory of Christian de Portzamparc. the artistic present. In 1932, for instance, no sooner had Philip Johnson, Henry-Russell Presenting Henri Labrouste at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine carries with Hitchcock, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., installed the Department’s legendary inaugural show, it its very own significance, given that his name and ideas crossed paths with our insti- Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, than plans were afoot for a show the following tution’s history, and his works are a testament to the values he defended. In 1858, he year on the commercial architecture of late-nineteenth-century Chicago, intended as the even sketched out a plan for reconstructing the Ecole Polytechnique on Chaillot hill, first in a series of shows tracing key episodes in the development of modern architecture though it would never be followed through. -

Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island New Jersey and New York July 2018 Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island New Jersey and New York July 2018 Foundation Document NEW JERSEY HUDSON JERSEY CITY RIVER NEW YORK Ferry tickets MANHATTAN N Railroad Terminal ew J e r Liberty State Park s e Ferry tickets y Battery f Castle Clinton e Park Ellis r National r Island y Monument Statue of Liberty National y EAST RIVER rr Monument e f rk o Y ew Governors Island Liberty N National Monument Island North 0 0.5 Kilometer BROOKLYN 0 0.5 Mile ELLIS ISLAND IMMIGRATION MUSEUM Interior shown at right Ferry Building American Immigrant Museum Wall of Honor Entrance Ellis Island Fort Gibson 0 75 meters 0 250 feet Buildings shown in gray are closed to the public. Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island Contents Mission of the National Park Service 1 Introduction 2 Part 1: Core Components 3 Brief Description of the Park 3 Statue of Liberty National Monument 3 Ellis Island 5 Park Purpose 6 Park Significance 7 Fundamental Resources and Values 8 Other Important Resources and Values 10 Interpretive Themes 10 Part 2: Dynamic Components 11 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments 11 Special Mandates 11 Administrative Commitments 11 Assessment of Planning and Data Needs 12 Analysis of Fundamental Resources and Values 13 Analysis of Other Important Resources and Values 28 Identification of Key Issues and Associated Planning and Data Needs 31 Planning and Data Needs 31 Part 3: Contributors 33 Statue of Liberty National Monument and -

Download File

CANON: ENGLISH ANTECEDENTS OF THE QUEEN ANNE IN AMERICA 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to thank my thesis advisor Janet W. Foster, adjunct assistant professor, Columbia University, for her endless positivity and guidance throughout the process. We share an appreciation for late nineteenth century American architecture and I feel very grateful to have worked with an advisor who is an expert on the period of time explored in this work. I would also like to thank my readers Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, professor, University of Washington, and Andrew Saint, author, for their time and assistance. Professor Ochsner thank you for your genuine interest in the topic and for contributing your expertise on nineteenth century American architecture, Henry Hobson Richardson and the Sherman house. Andrew thank you for providing an English perspective and for your true appreciation for the “Old English.” You are the expert on Richard Norman Shaw and your insight was invaluable in understanding Shaw’s works. This work would not have come to fruition without the insight and interest of a number of individuals in the topic. Thank you Sarah Bradford Landau for donating many of the books used in this thesis and whose article “Richard Morris Hunt, the Continental Picturesque and the ‘Stick Style’” was part of the inspiration for writing this thesis, and as this work follows where your article concluded. Furthermore, I would like to thank Andrew Dolkart, professor, Columbia University, for your recommendations on books to read and places to see in England, which guided the initial ideas for the thesis. There were many individuals who offered their time, assistance and expertise, thank you to: Paul Bentel, adjunct professor, Columbia University Chip Bohl, architect, Annapolis, Maryland Françoise Bollack, adjunct professor, Columbia University David W. -

Alexandre Dumas His Life and Works

f, t ''m^t •1:1^1 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNDERGRADUATE LIBRARY tu U X'^S>^V ^ ^>tL^^ IfO' The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924014256972 ALEXANDRE DUMAS HIS LIFE AND WORKS ALEXANDRE DUMAS (pere) HIS LIFE AND WORKS By ARTHUR F. DAVIDSON, M.A (Formerly Scholar of Keble College, Oxford) "Vastus animus immoderata, incredibilia, Nimis alta semper cupiebat." (Sallust, Catilina V) PHILADELPHIA J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY Ltd Westminster : ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO 1902 Butler & Tanner, The Selwood Printing Works, Frome, and London. ^l&'il^li — Preface IT may be—to be exact, it is—a somewhat presumptuous thing to write a book and call it Alexandre Dumas. There is no question here of introducing an unknown man or discovering an unrecognized genius. Dumas is, and has been for the better part of a century, the property of all the world : there can be little new to say about one of whom so much has already been said. Remembering also, as I do, a dictum by one of our best known men of letters to the effect that the adequate biographer of Dumas neither is nor is likely to be, I accept the saying at this moment with all the imfeigned humility which experience entitles me to claim. My own behef on this point is that, if we could conceive a writer who combined in himself the anecdotal facility of Suetonius or Saint Simon, with the loaded brevity of Tacitus and the judicial irony of Gibbon, such an one might essay the task with a reasonable prospect of success—though, after all, the probability is that he would be quite out of S5nnpathy with Dumas.