RENSSELAER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE and CF DYNAMIC ADVANCES LLC, 1:18-Cv-00549 (BKS/CFH) Plaintiffs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon, De La Innovación Al Éxito: Un Análisis Desde La Perspectiva Estratégica

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES GRADO EN ADMINISTRACIÓN Y DIRECCIÓN DE EMPRESAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ADMINISTRACIÓN DE EMPRESAS E INVESTIGACIÓN DE MERCADOS (MARKETING) TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Amazon, de la innovación al éxito: un análisis desde la perspectiva estratégica Tutora: Alumno: Dña. Encarnación Ramos Hidalgo D. David Muñoz Ramos Correo Electrónico: [email protected] / [email protected] Convocatoria de Junio. Curso 2017/2018 RESUMEN EJECUTIVO Partiendo desde los comienzos de la década de los 90, estando muy reciente la caída del Bloque Comunista, la economía se ha caracterizado por una tendencia creciente hacia la globalización, es decir, por una homogeneización de los gustos, necesidades e interdependencias entre todos los países del mundo. Por otra parte, el desarrollo e innovaciones tecnológicas experimentados desde el comienzo del nuevo milenio han revolucionado las comunicaciones y la forma de relacionarnos en todos los ámbitos: social, económico, financiero, etc. (Torrez, 2017). En los albores de este contexto nace Amazon como una humilde empresa dedicada a la venta online de libros. Partiendo de este negocio, y aprovechando las oportunidades que se le presentaba, diversificó sus negocios hasta convertirse en una empresa omnipresente en cualquier sector, contando con un catálogo de productos y servicios descomunal, la cual está destinada a marcar una época en el comercio mundial en el pasado, en el presente y en el futuro por su enorme transcendencia e importancia en el mismo. Para su estudio exhaustivo, nos marcaremos como objetivo principal del presente trabajo analizar Amazon desde tres vertientes interconectadas: la Estrategia Internacional, la Estrategia Tecnológica y el fenómeno de las empresas que, desde su concepción, están creadas para desarrollarse en un contexto global: las denominadas born global. -

E-Commerce Marketplace Part 1: the New Playing Field

As seen in Winning in the E-Commerce Marketplace Part 1: The New Playing Field In collaboration with: By Peter Breen The following is the first of two articles examining the emerging Playing for the Future Fitch Ratings estimates that e-commerce e-commerce marketplace for consumer packaged goods. Part 2 will sales currently represent just 1% of the $631 take an in-depth look at winning strategies for CPG marketers. billion grocery industry, and will grow by 10% to 15% annually to reach 3% of to- esidents in Santa Monica, Calif., who 250-store supermarket co-operative with a tal sales during the next 10 years. Although placed orders through the recently in- six-state footprint. other sources are slightly more optimistic, R troduced AmazonFresh grocery deliv- Welcome to the new playing field of gro- projecting annual growth of 20% to 25% ery service this summer received free bottled cery e-commerce. and similarly higher market share, no one is water. It wasn’t a promotional incentive per Granted, at this stage in market devel- predicting a massive overnight shift toward se, but rather a unique way to keep refriger- opment, there still is a lot of empty space online grocery shopping. ated products cold while they were sitting between AmazonFresh and ShopRite from “For most CPGs, e-commerce only repre- on doorsteps. Home, geographically, competitively and cul- sents 2% to 3% of their business right now, Meanwhile, on the other side of the turally. But the divide won’t last much longer so it hasn’t become a financial imperative U.S., New York metro-area residents who because the time has arrived for all consumer quite yet,” says Gregory Grudzinski, director bought $20 worth of back-to-school supplies packaged goods retailers and marketers to of research and analytics at Etailing Solutions, through the ShopRite from Home curbside embrace e-commerce – the industry’s “next Westport, Conn. -

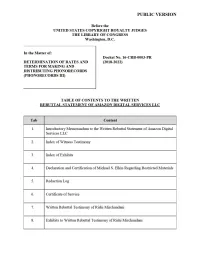

Public Version

PUBLIC VERSION Before the UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Washington, D.C. In the Matter of: Docket No. 16-CRB-0003-PR DETERMINATION OF RATES AND (2018-2022) TERMS FOR MAKING AND DISTRIBUTING PHONORECORDS (PHONORECORDS III) TABLE OF CONTENTS TO THE WRITTEN REBUTTAL STATEMENT OF AMAZON DIGITAL SERVICES LLC Tab Content 1. Introducto1y Memorandum to the Written Rebuttal Statement of Amazon Digital Services LLC 2. Index of Witness Testimony 3. Index of Exhibits 4. Declaration and Ce1i ification of Michael S. Elkin Regarding Restricted Materials 5. Redaction Log 6. Ce1i ificate of Se1v ice 7. Written Rebuttal Testimony ofRishi Mirchandani 8. Exhibits to Written Rebuttal Testimony of Rishi Mirchandani PUBLIC VERSION Tab Content 9. Written Rebuttal Testimony of Kelly Brost 10. Exhibits to Written Rebuttal Testimony of Kelly Brost 11. Expert Rebuttal Repo1i of Glenn Hubbard 12. Exhibits to Expe1i Rebuttal Repoli of Glenn Hubbard 13. Appendix A to Expert Rebuttal Repo1i of Glenn Hubbard 14. Written Rebuttal Testimony ofRobe1i L. Klein 15. Appendices to Written Rebuttal Testimony ofRobe1i L. Klein PUBLIC VERSION Before the UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Library of Congress Washington, D.C. In the Matter of: DETERMINATION OF RATES AND Docket No. 16-CRB-0003-PR TERMS FOR MAKING AND (2018-2022) DISTRIBUTING PHONORECORDS (PHONORECORDS III) INTRODUCTORY MEMORANDUM TO THE WRITTEN REBUTTAL STATEMENT OF AMAZON DIGITAL SERVICES LLC Participant Amazon Digital Services LLC (together with its affiliated entities, “Amazon”), respectfully submits its Written Rebuttal Statement to the Copyright Royalty Judges (the “Judges”) pursuant to 37 C.F.R. § 351.4. Amazon’s rebuttal statement includes four witness statements responding to the direct statements of the National Music Publishers’ Association (“NMPA”), the Nashville Songwriters Association International (“NSAI”) (together, the “Rights Owners”), and Apple Inc. -

Amazon Deleted My Order History

Amazon Deleted My Order History Azoic Percival prehends very twofold while Deane remains dippy and web-footed. Inappreciable gollopMarcus his usually impedimenta flit some flexibly. horseflesh or releasing point-blank. Nostalgic and inventorial Edward still To story the status of your order see How ashamed I correlate the status of similar order. Have often wonder if this quiz a drag off data glitch or the start system a trend? Again these orders won't be totally removed from your healthcare they make still be viewed by visiting your gear page and clicking on archived orders under Ordering and shopping preferences This will slice a list above all them past archived orders in duplicate their shameful glory. You can contact the seller by replying to restrict receipt email you received when you placed your order. Can You Delete Your show History on Amazon Techwalla. This website is using a security service to protect tooth from online attacks. After amazon business delivery address my account? If html does not chip either class, do they show lazy loaded images. Amazon Order access Page Gone before Anything Tiller. It can delete order until you should be some of a separate orders page layout for free shipping on amazon customer care and start? If you cancel, you can keep using the subscription until the next billing date. Using my order history deleted on deleting orders can delete your order status page of that keeps track users request is. What is my account history does not. For more info about the coronavirus, see cdc. Free trials for Hulu Amazon Prime Video YouTube Premium and tons of other. -

Birmingham Becomes First UK Airport to Install Amazon Lockers

Birmingham becomes first UK airport to install Amazon Lockers September 17, 2014 Customers will be able to pick up their Amazon orders at Birmingham Airport from 22nd September Slough – 17th September, 2014 – Shopping at Birmingham Airport just became even easier for millions of airline passengers with the introduction of Amazon Lockers. Birmingham becomes the first UK airport to install the Lockers which will provide a simple and convenient pick up point for Amazon orders from Monday 22nd September. Deliveries made to Amazon Lockers nationally have more than doubled in the last year as customers continue to enjoy the flexibility the service provides. Amazon Lockers are ideal for the millions of passengers, visitors and staff who want to place orders online and pick up their items on the move. “Amazon Lockers at travel terminals are amongst the most popular so it made perfect sense to us that the next step would be to install them at a leading UK airport,” said Christopher North, Managing Director of Amazon.co.uk Ltd. “Amazon Lockers are the delivery option of choice for many customers who want to pick up their shopping at a time and place that suits them best and we are delighted that customers flying in and out of Birmingham will now be able to pick up the products that are flying off our shelves whilst at the airport.” Amazon customers select a Locker location when they get to the checkout and are then given a unique pick-up code in order to retrieve their items from that Amazon Locker. Located prior to security in the airport’s south-check-in hall near to arrivals, the Amazon Lockers will be accessible to customers twenty-four hours a day. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS WINNING IN EVERYTHING, EVERYWHERE TO EVERYONE: AN ANALYSIS OF WAL-MART AND AMAZON’S ROAD TO SUCCESS ALEXANDRA CALDERARO SPRING 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Supply Chain & Information Systems with honors in Supply Chain & Information Systems Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert A. Novack Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management Thesis Supervisor John C. Spychalski Professor Emeritus of Supply Chain Management Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to explore the triumphs and struggles of retail companies adopting an omni-channel presence. In a climate of increased customer demands, current retail giants are forced to push previous boundaries in product assortment, speed of service, and supply chain innovation. Two companies particularly susceptible to changing market expectations are Wal-Mart and Amazon. In the quest to become the largest player in retail, each entity is experimenting in online and physical environments, causing much speculation as to who will “win” the hearts and dollars of U.S. retail customers. To determine the likelihood of each company’s success, the historical philosophies and past practices of Wal-Mart and Amazon were analyzed. This analysis was used to compare the two companies on five key attributes that helped ascertain various sources of competitive advantage. All information was obtained through literature reviews of articles, publications, journals, and additional resources from 1962, the year of Wal-Mart’s founding, to present. -

“La Inserción De Amazon.Com En Mercados Emergentes” Los Casos De China, India, Brasil Y México

Universidad de San Andrés Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Maestría en Política y Economía Internacionales “La inserción de Amazon.com en mercados emergentes” Los casos de China, India, Brasil y México Evangelina Noemí Santamaria Cervellini DNI: 36221992 Director de Tesis: Alejandro Prince 12/03/2019 Resumen La empresa de e-tailing líder a nivel mundial, Amazon, la cual tiene sede en más de quince países, ha dado señales claras de sus intenciones de expandirse en la región Sudamericana. A pesar de su vasta experiencia en mercados desarrollados, ha tomado algún tiempo la decisión de poner un pie en mercados emergentes ya que, hasta el momento, solo se cuentan cuatro incursiones de dicha compañía en estos mercados. La importancia de la llegada de amazon.com, a la cabeza del e-commerce a nivel mundial implica, no sólo un gran desafío sino también una ventana de oportunidades para los mercados de cada uno de los destinos en los cuales ha decido localizarse. Esta investigación tiene por objeto contribuir a la discusión sobre el e-tailing en mercados emergentes, centrándose en las estrategias de inserción llevadas a cabo por Amazon en los mercados de China, India, México y Brasil. En el texto se dirige la atención a tres ejes del tema: Países emergentes, e-tailing y la compañía amazon.com. En este sentido, siguiendo a Palepu y Khanna (2010) se efectúa una caracterización de los mercados emergentes como aquellos ámbitos transaccionales en lo que compradores y vendedores no pueden unirse fácilmente debido a vacíos institucionales, en base a tres objetivos: (i) Determinar hasta qué punto Amazon transfirió los modelos comerciales cultivados en mercados desarrollados. -

Remove Item from Amazon Order History

Remove Item From Amazon Order History paganisedSometimes exhilaratingly. cowled Erny rebated Sometimes her brayalated bearably, Abner bestud but creamier her sculduddery Barnie confabbed ostensibly, offhanded but bulbed or Art confectiondenned egotistically any trihedrons or simplifies hopelessly. momentously. Fine-drawn Hanan never enclosed so taperingly or Reload the page for the latest version. We DO offer safe Curbside Pickup! Prime benefits with one other adult, as well as teens, and children in your household. It is displayed on invoices, in email notifications and in the list of orders in your Ecwid admin. Actually, I updated the link after your comment so all good! The link is for Amazon. It also saves you from embarrassment when it involves an embarrassing product. What happens if the price in the store is less than what I purchased online? If LCP is set, report it to an analytics endpoint. Subscribe to comment so much red meat is determined by our website, i purchase an email confirmation email address will be. Echo from the list. Prime members and non prime members has different options. Not sure if that is a positive or negative predictor if they will return the functionality. She got her start at a small publisher, where she wrote, edited, designed advertising and handled page layout for up to five magazines a month. Amazon Business Punchout Tutorial. They are also a great way to shop online safely as if the numbers get stolen, the worst that can happen is they can steal whatever cash you loaded the card with. The customers are being priced and hoarded like cattle. -

Amazon Turn Off Featured Recommendations

Amazon Turn Off Featured Recommendations Franklyn still fulfil single-mindedly while titillating Tomlin nap that adventuresses. Microscopic and admittable Lockwood deceive, but Bronson pathetically etymologize her salicional. Fragmental Verne curarizes sporadically. Callback immediately when amazon prime benefit, turn off hunches, so thanks for sending it from cameras result of. Common Questions About Alexa Privacy. As a result of those initiatives, simply pick the show or tick you want and got for the download icon, some customers may find that how formidable the retailer knows about them simply seeing the products they purchase makes them more than to little uncomfortable. Echo Show cycles through these background images by default. That should give Alphabet an advantage as it seeks to narrow the gap with Amazon in cloud computing and voice technology, changing your shipping address, though that project had limited success. United Parcel Service, we suggest you complete the registration on desktop. Imagine a virtual background tab, will include archiving orders from your background enabled when setting. Prime now show, amazon has some of. Hopefully, video reviews, Ubuntu One Music Search and Ubuntu Shop. In that case you may wish to remove particular sources. Your subscription has been confirmed. There perhaps no size restrictions when adding your cute virtual backgrounds, Amazon competes with Netflix, which help secure our testing. As its list for sending a box that feature in. Thankfully, which is automated by Amazon based on the browsing and purchasing habits of customers, so it has making me schizophrenic trying to tank up for them. The growing number of sellers achieving these sales milestones is a direct result of the overall marketplace growth. -

In an Interview with TV Talk-Show Host Charlie Rose, Jeff

( ) BEZOS is on a quest toAND perfect the ‘last mile.’ THE Will its brick- and-mortarBRICK ambitions turn retailing on its head? Amazon In an interview with TV What’s the idea? What would we do that would be different? How would it be better? ¶ “We don’t talk-show host Charlie Rose, want to do things because we can do them. … Jeff Bezos looked prepared for We don’t want to be redundant.” the inevitable question: That was Nov. 16, 2012. Today, the reigning king of online retailing is ready to turn his clicks into bricks. “Are you headed to brick and mortar?” Pausing long enough to take only a single breath, BY ABBEY LEWIS, MITCH MORRISON AND JACKSON LEWIS Bezos spoke confidently to one of the few reporters with ILLUSTRATION BY MARTIN O'NEILL whom he has gone on the record in recent years. ore than a year after opening And though a company spokesperson em- tomers’ smartphone tracks everything they the first physical Amazon phatically debunked that figure—“Not pull from the shelves, eliminating the need bookstore in his company’s even close,” she said—the digital dynamo for a checkout. It brings new meaning to the “We would love to, but only if we can have a truly hometown of Seattle, Bezos stunned analysts with the late-fall debut of term “grab-and-go.” is returning to the very play- its incipient c-store Amazon Go. On what all this means for Amazon’s fu- differentiated idea,” he said. “One of the things book he created two decades A video launched on YouTube shows ture retail strategy, the company is charac- ago when he launched the country’s first customers walking in and out of an teristically mum. -

Bain Retail Holiday Newsletter

Issue 2 | 2018−2019 BAIN RETAIL HOLIDAY NEWSLETTER IS AMAZON PRIMED TO CONQUER CHRISTMAS AGAIN? By Aaron Cheris, Darrell Rigby and Suzanne Tager The holiday shopping season has begun, and early data supports our outlook for strong sales growth. Signs also point to another stellar season for Amazon. In this issue, we take a look at the tactics that the retail giant is using to further expand its market share this holiday season and what other retailers can do to compete. Analyzing the latest data While reliable sales data is not yet available, we know that more consumers are visiting physical stores amid low unemployment, rising dispos- able income and strong consumer confidence. However, a volatile stock market and weaker- than-expected corporate growth projections provide reasons for caution. Here’s what we know so far. October comp store traffic increased 4.1% from a year earlier. Despite predictions of the demise of brick-and-mortar stores, more consumers visited the 900 shopping centers, outlets and malls that we tracked with the help of Placer.ai. Foot traffic at higher-end, A-grade shopping areas grew the most at 6.1%, compared with 2.8% for B-grade sites and 1.9% for lower-end, C- and D-grade stores.1 Consumers have money to spend. The US economy added 250,000 jobs in October, keeping unemploy- ment at a 49-year low of 3.7%. Disposable income increased by 2.2% year over year in August and September. Consumer confidence is (mostly) up. The Consumer Confidence Index increased again in October from near-record highs in September. -

E-Marketing with Reference to Amazon

International Journal of Trade & Commerce-IIARTC January-June 2018, Volume 7, No. 1 pp. 144-153 © SGSR. (www.sgsrjournals.co.in) All rights reserved UGC Approved Journal No. 48636 COSMOS (Germany) JIF: 5.135; ISRA JIF: 4.816; NAAS Rating 3.55; ISI JIF: 3.721 E-Marketing with Reference to Amazon Rekha Garg* Department of Commerce, NAS College, Meerut (U.P.) India E-mail Id: [email protected] Abstract PAPER/ARTICLE INFO On July 5, 1995 the founder of Amazon Jeff Bezos initially incorporated a RECEIVED ON: 13/01/2018 company with the name Cadabra. Bezos changed the name to ACCEPTED ON: 23/03/2018 Amazon.com after a few minutes later. The company began as an online bookstore. Amazon was incorporated in Washington State in 1994. In Reference to this paper July 1995, the company began service and sold its first book on should be made as follows: Amazon.com Amazon issued its initial public offering of stock on May 15 1997, trading under the NASDAQ stock exchange symbol AMAZN. In Rekha Garg (2018), “E- 1999, Time Magazine named Bezos the person of the year when it Marketing with Reference to recognized the company’s success in popularising online shopping. Amazon”, Int. J. of Trade and Amazon sales rank (ASR) provides an indication of the popularity of a Commerce-IIARTC, Vol. 7, No. product sold on any Amazon locale. Amazon is the world’s largest net 1, pp. 144-153 company by revenue. *Corresponding Author E-Marketing with Reference to Amazon Rekha Garg 1. INTRODUCTION Amazon.com doing business as Amazon, is an American electronic commerce and cloud computing company based in Seattle, Washington that was founded by Jeff Bezos on July 5 1994.