Spatium No 34 FINAL ZA STAMPU-Sa Slikama.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pravilnik O Utvrđivanju Vodnih Tela Površinskih I Podzemnih Voda

Na osnovu člana 7. stav 4. Zakona o vodama ("Službeni glasnik RS", broj 30/10), Ministar poljoprivrede, šumarstva i vodoprivrede, donosi Pravilnik o utvrđivanju vodnih tela površinskih i podzemnih voda Pravilnik je objavljen u "Službenom glasniku RS", br. 96/2010 od 18.12.2010. godine. Član 1. Ovim pravilnikom utvrđuju se vodna tela površinskih i podzemnih voda. Član 2. Naziv vodnog tela površinskih voda iz člana 1. ovog pravilnika, naziv vodotoka na kome se nalazi vodno telo, kategorija (reka, veštačko vodno telo, značajno izmenjeno vodno telo), dužina i šifra vodnog tela, kao i vodno područje na kome se nalazi vodno telo dati su u Prilogu 1. koji je odštampan uz ovaj pravilnik i čini njegov sastavni deo. Naziv vodnog tela površinskih voda - jezera iz člana 1. ovog pravilnika, površina vodenog ogledala i vodno područje na kome se nalazi vodno telo dati su u Prilogu 2. koji je odštampan uz ovaj pravilnik i čini njegov sastavni deo. Naziv vodnog tela podzemnih voda iz člana 1. ovog pravilnika, površina i šifra vodnog tela, hidrogeološka jedinica iz Vodoprivredne osnove Republike Srbije, kao i vodno područje na kome se nalazi vodno telo dati su u Prilogu 3. koji je odštampan uz ovaj pravilnik i čini njegov sastavni deo. Član 3. Ovaj pravilnik stupa na snagu osmog dana od dana objavljivanja u "Službenom glasniku Republike Srbije". Broj 110-00-299/2010-07 U Beogradu, 10. decembra 2010. godine Ministar, dr Saša Dragin, s.r. Prilog 1. VODNA TELA POVRŠINSKIH VODA - VODOTOCI Dužina Redni Kategorija vodnog Šifra vodnog Vodno Naziv vodnog tela -

Sustainable Tourism for Rural Lovren, Vojislavka Šatrić and Jelena Development” (2010 – 2012) Beronja Provided Their Contributions Both in English and Serbian

Environment and sustainable rural tourism in four regions of Serbia Southern Banat.Central Serbia.Lower Danube.Eastern Serbia - as they are and as they could be - November 2012, Belgrade, Serbia Impressum PUBLISHER: TRANSLATORS: Th e United Nations Environment Marko Stanojević, Jasna Berić and Jelena Programme (UNEP) and Young Pejić; Researchers of Serbia, under the auspices Prof. Branko Karadžić, Prof. Milica of the joint United Nations programme Jovanović Popović, Violeta Orlović “Sustainable Tourism for Rural Lovren, Vojislavka Šatrić and Jelena Development” (2010 – 2012) Beronja provided their contributions both in English and Serbian. EDITORS: Jelena Beronja, David Owen, PROOFREADING: Aleksandar Petrović, Tanja Petrović Charles Robertson, Clare Ann Zubac, Christine Prickett CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Prof. Branko Karadžić PhD, GRAPHIC PREPARATION, Prof. Milica Jovanović Popović PhD, LAYOUT and DESIGN: Ass. Prof. Vladimir Stojanović PhD, Olivera Petrović Ass. Prof. Dejan Đorđević PhD, Aleksandar Petrović MSc, COVER ILLUSTRATION: David Owen MSc, Manja Lekić Dušica Trnavac, Ivan Svetozarević MA, PRINTED BY: Jelena Beronja, AVANTGUARDE, Beograd Milka Gvozdenović, Sanja Filipović PhD, Date: November 2012. Tanja Petrović, Mesto: Belgrade, Serbia Violeta Orlović Lovren PhD, Vojislavka Šatrić. Th e designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Acknowledgments Th is publication was developed under the auspices of the United Nations’ joint programme “Sustainable Tourism for Rural Development“, fi nanced by the Kingdom of Spain through the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDGF). -

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Public Disclosure Authorized FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF YUGOSLAVIA BREAKING WITH THE PAST: THE PATH TO STABILITY AND GROWTH Volume II: Assistance Priorities and Public Disclosure Authorized Sectoral Analyses Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS………………………………………………………...viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT……………………………………………………………………….. ix CHAPTER 1. AN OVERVIEW OF THE ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND TRANSITION PROGRAM…………………………………………………………………………………….... 1 A. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..... 1 B. The Government’s medium-term Challenges…………………………………………..... 3 C. Medium-term External Financing Requirements………………………………….……... 4 D. The 2001 Program………………………………………………………………………... 8 E. Implementing the Program………………………………………………………….…....13 CHAPTER 2. FISCAL POLICY AND MANAGEMENT………………….…………………..15 A. Reducing Quasi Fiscal Deficits and Hidden Risks…………………………………….. ..16 B. Transparency and Accountability of Public Spending………………….………………..27 C. Public Debt Management………………………………………………………………...34 D. Tax Policy and Administration…………………………………………….…………... ..39 CHAPTER 3. TRADE………………………………………...…………………….…………..48 A. Patterns of Trade in Goods and Services ……………………………..………..……… ..48 B. Trade Policies: Reforms to date and plans for the future………………………………...51 C. Capacity to Trade: Institutional and other constraints to implementation…………….....55 D. Market Access: The global, European and regional dimension……………………….. ..57 E. Policy recommendations………………………………………………………………....60 F. Donor Program……………………………………………………………….…………..62 -

Ph4.3 Key Characteristics of Social Rental Housing

OECD Affordable Housing Database – http://oe.cd/ahd OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs - Social Policy Division PH4.3 KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF SOCIAL RENTAL HOUSING Definitions and methodology This indicator presents information from the OECD Questionnaire on Social and Affordable Housing on the definition and characteristics of social rental housing programmes, and provides details on the different methods used to define rent levels and rent increases, the eligibility of beneficiaries, and dwelling allocation. For the purpose of this indicator, the following definition of social rental housing was used: residential rental accommodation provided at sub-market prices and allocated according to specific rules (Salvi del Pero, A. et al., 2016). Based on this definition, surveyed countries provided information on a range of different supply-side measures in the rental sector, see Table 4.3a below. Key findings In total, 32 countries report the existence of some form of social rental housing. Definitions of social rental housing differ across countries (see Table PH4.3.1). Further, many countries report having more than one type of rental housing that responds to administrative procedures (as opposed to market mechanisms), with different characteristics in terms of providers, target groups and financing arrangements. The complexity of the social housing sector in some countries is due in part to its long history, which has seen different phases and different stakeholders involved over time. There are also a number of regional specificities that affect the size and functioning of the social housing stock across countries. For instance, in most Central and Eastern European countries (Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic), the social rental housing stock is quite small (see indicator PH4.2), while there is a much larger share of the population that owns their dwellings outright, as a result of the mass housing privatisation since 1990. -

Подкласс Exogenia Collin, 1912

Research Article ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.ecol-mne.com Contribution to the knowledge of distribution of Colubrid snakes in Serbia LJILJANA TOMOVIĆ1,2,4*, ALEKSANDAR UROŠEVIĆ2,4, RASTKO AJTIĆ3,4, IMRE KRIZMANIĆ1, ALEKSANDAR SIMOVIĆ4, NENAD LABUS5, DANKO JOVIĆ6, MILIVOJ KRSTIĆ4, SONJA ĐORĐEVIĆ1,4, MARKO ANĐELKOVIĆ2,4, ANA GOLUBOVIĆ1,4 & GEORG DŽUKIĆ2 1 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Studentski trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 3 Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Dr Ivana Ribara 91, 11070 Belgrade, Serbia 4 Serbian Herpetological Society “Milutin Radovanović”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 5 University of Priština, Faculty of Science and Mathematics, Biology Department, Lole Ribara 29, 38220 Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia 6 Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Vožda Karađorđa 14, 18000 Niš, Serbia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Received 28 March 2015 │ Accepted 31 March 2015 │ Published online 6 April 2015. Abstract Detailed distribution pattern of colubrid snakes in Serbia is still inadequately described, despite the long historical study. In this paper, we provide accurate distribution of seven species, with previously published and newly accumulated faunistic records compiled. Comparative analysis of faunas among all Balkan countries showed that Serbian colubrid fauna is among the most distinct (together with faunas of Slovenia and Romania), due to small number of species. Zoogeographic analysis showed high chorotype diversity of Serbian colubrids: seven species belong to six chorotypes. South-eastern Serbia (Pčinja River valley) is characterized by the presence of all colubrid species inhabiting our country, and deserves the highest conservation status at the national level. -

New Deal for Housing Justice: a Housing Playbook for the New

New Deal for Housing Justice A Housing Playbook for the New Administration JANUARY 2021 About this Publication New Deal for Housing Justice is the result of the input, expertise, and lived experience of the many collaborators who participated in the process. First and foremost, the recommendations presented in this document are rooted in the more than 400 ideas shared by grassroots leaders and advocates in response to an open call for input launched early in the project. More than 100 stakeholder interviews were conducted during the development of the recommendations, and the following people provided external review: Afua Atta-Mensah, Rebecca Cokley, Natalie Donlin-Zappella, Edward Golding, Megan Haberle, Priya Jayachandran, Richard Kahlenberg, Mark Kudlowitz, Sunaree Marshall, Craig Pollack, Vincent J. Reina, Sherry Riva, Heather Schwartz, Thomas Silverstein, Philip Tegeler, and Larry Vale. Additional information is available on the companion website: http://www.newdealforhousingjustice.org/ Managing Editor Lynn M. Ross, Founder and Principal, Spirit for Change Consulting Contributing Authors Beth Dever, Senior Project Manager, BRicK Partners LLC Jeremie Greer, Co-Founder/Co-Executive Director, Liberation in a Generation Nicholas Kelly, PhD Candidate, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Rasmia Kirmani-Frye, Founder and Principal, Big Urban Problem Solving Consulting Lindsay Knotts, Independent Consultant and former USICH Policy Director Alanna McCargo, Vice President, Housing Finance Policy Center, Urban Institute Ann Oliva, Visiting -

Social Housing and the Affordability Crisis

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Fall 11-25-2020 Social Housing and the Affordability Crisis: A Study of the Effectiveness of French and American Social Housing Systems in Meeting the Increasing Demand for Affordable Housing Claire Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Social Policy Commons, and the Social Welfare Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Claire, "Social Housing and the Affordability Crisis: A Study of the Effectiveness of French and American Social Housing Systems in Meeting the Increasing Demand for Affordable Housing" (2020). Honors Theses. 1592. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1592 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOCIAL HOUSING AND THE AFFORDABILITY CRISIS: A STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FRENCH AND AMERICAN SOCIAL HOUSING SYSTEMS IN MEETING THE INCREASING DEMAND FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING By: Claire Ann Sullivan A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi November 2020 Approved by: _________________________ Advisor: Dr. Joshua First _________________________ Reader: Dr. William Schenck _________________________ Reader: Dr. James Thomas © 2020 Claire Ann Sullivan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The demand for affordable housing across OECD countries has sky-rocketed as the number of those cost-burdened by housing continues to increase each year. -

Download Download

UNIVERSITY THOUGHT doi:10.5937/univtho7-15336 Publication in Natural Sciences, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2017, pp. 1-27. Original Scientific Paper A CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE OF THE BALKAN LEPIDOPTERA. SOME PYRALOIDEA (LEPIDOPTERA: CRAMBIDAE & PYRALIDAE) ENCOUNTERED RECENTLY IN SOUTHERN SERBIA, MONTENEGRO, THE REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA AND ALBANIA COLIN W. PLANT1*, STOYAN BESHKOV2, PREDRAG JAKŠIĆ3, ANA NAHIRNIĆ2 114 West Road, Bishops Stortford, Hertfordshire, CM23 3QP, England 2National Museum of Natural History, Sofia, Bulgaria 3Faculty of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Priština, Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia ABSTRACT Pyraloidea (Lepidoptera: Crambidae & Pyralidae) were sampled in the territories of southern Serbia, Montenegro, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Albania on a total of 53 occasions during 2014, 2016 and 2017. A total of 173 species is reported here, comprising 97 Crambidae and 76 Pyralidae. Based upon published data, 29 species appear to be new to the fauna of Serbia, 5 species are new to the fauna of Macedonia and 37 are new to the fauna of Albania. The data are discussed. Keywords: Faunistics, Serbia, Montenegro, Republic of Macedonia, Albania, Pyraloidea, Pyralidae, Crambidae. of light trap. Some sites were visited on more than one occasion; INTRODUCTION others were sampled once only. Pyraloidea (Lepidoptera: Crambidae and Pyralidae) have As a by-product of this work, all remaining material from been examined in detail in the neighbouring territory of the the traps was returned to Sofia where Dr Boyan Zlatkov was Republic of Bulgaria and the results have been published by one given the opportunity to extract the Tortricoidea. The remaining of us (Plant, 2016). That work presented data for the 386 species material was retained and sent by post to England after the end of and 3 additional subspecies known from that country. -

South East Asia Resources Limited to Be Renamed Jadar Lithium Limited

3&1-"$&.&/5 PROSPECTUS South East Asia Resources Limitedto be renamed Jadar Lithium Limited 4VCKFDUUP%FFEPG$PNQBOZ"SSBnHFNFOU ACN 009 144 503 &ŽƌĂŶŽĨĨĞƌŽĨƵƉƚŽϮϱϬ͕ϬϬϬ͕ϬϬϬ ^ŚĂƌĞƐĂƚĂŶŝƐƐƵĞƉƌŝĐĞŽĨΨϬ͘ϬϮ ĞĂĐŚƚŽƌĂŝƐĞƵƉƚŽĂƚŽƚĂůŽĨΨϱ͕ϬϬϬ͕ϬϬϬ ;WƵďůŝĐKĨĨĞƌͿ;ďĞĨŽƌĞĐŽƐƚƐͿ͘ dŚŝƐZĞƉůĂĐĞŵĞŶƚWƌŽƐƉĞĐƚƵƐĂůƐŽ ĐŽŶƚĂŝŶƐƚŚĞ^ĞĐŽŶĚĂƌLJKĨĨĞƌƐ͘ IMPORTANT INFORMATION This 3FQMBDFNFOU Prospectus is a re-compliance prospectus for the purposes of satisfying Chapters 1 and 2 of the ASX Listing Rules and to satisfy the ASX requirements for re-listing following a change to the nature and scale of the Company’s activities. All references to Securities in this 3FQMBDFNFOUProspectus are made on the basis that the Consolidation, unless otherwise stated, for which Shareholder approval XBs PCUBJOFEaU the General Meeting held on 0DUPCFS 2017, has taken effect. This is an important document that should be read in its entirety. *GZPVEPOPUVOEFSTUBOEJUZPVTIPVMEDPOTVMUZPVSQSPGFTTJPOBMBEWJTFST XJUIPVUEFMBZ*OWFTUNFOUJOUIF4IBSFTPGGFSFEQVSTVBOUUPUIJT 3FQMBDFNFOU1SPTQFDUVTTIPVMECFSFHBSEFEBTIJHIMUZTQFDVMBUJWFJO OBUVSF BOEJOWFTUPSTTIPVMECFBXBSFUIBUUIFZNBZMPTFTPNFPSBMMPGUIFJS JOWFTUNFOU3FGFSUP4FDUJPOGPSBTVNNBSZPGUIFLFZSJTLTBTTPDJBUFEXJUI BOJOWFTUNFOUJOUIF4IBSFT South East Asia Resources Limited (to be renamed 'Jadar Lithium Limited') (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) ACN 009 144 503 PROSPECTUS For an offer of up to 250,000,000 Shares at an issue price of $0.02 each to raise up to a total of $5,000,000 (Public Offer) (before costs). This Prospectus also contains the following Secondary Offers: 1. an offer of 37,500,000,000 Shares in consideration for the acquisition of all shares in Centralist (Consideration Offer); 2. an offer of 65,250,000 Options for no consideration to investors who participated in the Prior Placement (Placement Options Offer); 3. an offer of up to 12,500,000 Shares to Dempsey Resources (or its nominee) in lieu of corporate advisory fees for services rendered to the Company (Advisor Offer); and 4. -

Zone Na Teritoriji Grada Beograda Četvrtak, 10 Mart 2011 00:00

Zone na teritoriji Grada Beograda četvrtak, 10 mart 2011 00:00 Odlukom o određivanju zona na teritoriji Grada Beograda (Sl. list grada Beograda", br. 60/2009 i 45/2010) određene su zone kao jedan od kriterijuma za utvrđivanje visine lokalnih komunalnih taksi, naknade za korišćenje građevinskog zemljišta i naknade za uređivanje građevinskog zemljišta. Takođe, zone određene tom odlukom primenjuju se i kao kriterijum za utvrđivanje visine zakupnine za poslovni prostor na kome je nosilac prava korišćenja grad Beograd. Na teritoriji grada Beograda postoje devet zona u zavisnosti od tržišne vrednosti objekata i zemljišta, komunalne opremljenosti i opremljenosti javnim objektima, pokrivenosti planskim dokumentima i razvojnim mogućnostima lokacije, kvaliteta povezanosti lokacije sa centralnim delovima grada, nameni objekata i ostalim uslovljenostima. Spisak zona - Prva zona - U okviru prve zone nalaze se: - Zona zaštite zelenila - Područje uže zone zaštite vodoizvorišta za Beograd - Područje uže zone zaštite vodoizvorišta za naselje Obrenovac - Ekstra zona stanovanja - Ekstra zona poslovanja - Druga zona - Treća zona - Četvrta zona - Peta zona - Šesta zona - Sedma zona 1 / 25 Zone na teritoriji Grada Beograda četvrtak, 10 mart 2011 00:00 - Osma zona - Zona specifičnih namena Ovde možete preuzeti grafički prikaz zona u Beogradu. Napomene: 1. U slučaju neslaganja tekstualnog dela i grafičkog priloga, važi grafički prilog . 2. Popis katastarskih parcela i granice katastarskih opština su urađene na osnovu raspoloživih podloga i ortofoto snimaka iz -

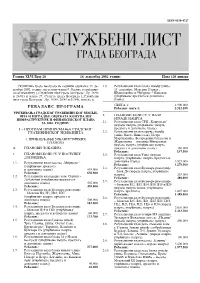

Grada Beograda

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina XLVI Broj 28 16. decembar 2002. godine Cena 120 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 13. de- 1.8. Regulacioni plan bloka izme|u ulica: cembra 2002. godine, na osnovu ~lana 9. Odluke o gra|evin- 14. decembra, Maksima Gorkog, skom zemqi{tu („Slu`beni list grada Beograda”, br. 16/96 [umatova~ke i ^uburske – Kikevac i 26/01) i ~lana 27. Statuta grada Beograda („Slu`beni (utvr|ivawe predloga i dono{ewe list grada Beograda”, br. 18/95, 20/95 i 21/99), donela je plana) –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– SVEGA 1: 1.900.000 REBALANS PROGRAMA Rebalans svega 1: 2.312.100 –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– URE\IVAWA GRADSKOG GRA\EVINSKOG ZEMQI- [TA I IZGRADWE OBJEKATA KOMUNALNE 2. PLANOVI KOJI SU U FAZI INFRASTRUKTURE I FINANSIJSKOG PLANA IZRADE NACRTA ZA 2002. GODINU 2.1. Regulacioni plan SRC „Ko{utwak” (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, á – PROGRAM PRIPREMAWA GRADSKOG predloga i dono{ewe plana) GRA\EVINSKOG ZEMQIŠTA 2.2. Regulacioni plan podru~ja izme|u ulica: Kneza Vi{eslava, Petra 1. PRIBAVQAWE URBANISTI^KIH Martinovi}a, Beogradskih bataqona i PLANOVA @arkova~ke – lokacija Mihajlovac (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, A. PLANOVI LOKACIJA predloga i dono{ewe plana) 160.000 Rebalans: 137.500 1. PLANOVI KOJI SU U POSTUPKU 2.3. Regulacioni plan Umke (izrada DONOŠEWA nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, predloga i 1.1. Regulacioni plan naseqa „Mirijevo” dono{ewe plana) 3.925.000 (utvr|ivawe predloga Rebalans: 3.279.900 2.4. Regulacioni plan Bulevara revolucije i dono{ewe plana) 635.000 – blok D6 (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe Rebalans: 656.600 nacrta) 235.000 1.2. -

Slu@Beni List Grada Beograda

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina XLVIII Broj 10 26. maj 2004. godine Cena 120 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 25. ma- ma stepenu obaveznosti: (a) nivo 2006. godine za planska ja 2004. godine, na osnovu ~lana 20. Zakona o planirawu i re{ewa za koja postoje argumenti o neophodnosti i opravda- izgradwi („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 47/03) i ~l. 11. i nosti sa dru{tvenog, ekonomskog i ekolo{kog stanovi{ta; 27. Statuta grada Beograda („Slu`beni list grada Beogra- (b) nivo 2011. godine za planske ideje za koje je oceweno da da", br. 18/95, 20/95, 21/99, 2/00 i 30/03), donela je postoji mogu}nost otpo~iwawa realizacije uz podr{ku fondova Evropske unije za kandidatske i pristupaju}e ze- REGIONALNI PROSTORNI PLAN mqe, me|u kojima }e biti i Srbija; (v) nivo iza 2011. godine, kao strate{ka planska ideja vodiqa za ona re{ewa kojima ADMINISTRATIVNOG PODRU^JA se dugoro~no usmerava prostorni razvoj i ure|ivawe teri- GRADA BEOGRADA torije grada Beograda, a koja }e biti podr`ana struktur- nim fondovima Evropske unije, ~iji }e ~lan u optimalnom UVODNE NAPOMENE slu~aju tada biti i Republika Srbija. Regionalni prostorni plan administrativnog podru~ja Planska re{ewa predstavqaju obavezu odre|enih insti- grada Beograda (RPP AP Beograda) pripremqen je prema tucija u realizaciji, odnosno okosnicu javnog dobra i javnog Odluci Vlade Republike Srbije od 5. aprila 2002. godine interesa, uz istovremenu punu podr{ku za{titi privatnog („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 16/02).