Chapter 2 Is Intervention Necessary?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of the Evidence Base for WASH Interventions in Emergency Responses / Relief Operations

A Review of the Evidence Base for WASH interventions in Emergency Responses / Relief Operations A Review of the Evidence Base for WASH interventions in Emergency Responses Discussion document Submitted by Jonathan Parkinson January 2009 January 2009 Page 1 of 56 A Review of the Evidence Base for WASH interventions in Emergency Responses / Relief Operations Executive summary Inadequate sanitation, inadequate water supplies and poor hygiene are critical determinants for survival of victims of natural disasters and conflict situations, especially in the initial stages of a disaster. The most significant are diarrheal diseases and infectious diseases transmitted by the faeco-oral route nd a combination of these factors means that people affected by disasters are also generally much more susceptible to illness and death from disease The traditional response by relief agencies in emergency situations has been to install water supply points and latrines. But experiences have clearly demonstrated the limitations of this approach. More recently hygiene promotion has taken increasingly greater predominance as an integral part of relief agency operations. However, these experiences are diverse and this has led to questions about which type of hygiene promotion activity is most effective and how. Consequently, in the course of the extensive inter-agency consultation, it has emerged that much of the existing evidence base which underpins decision-making for WASH interventions in relief operations is extrapolated from the development sector. It is unclear to the extent to which it is appropriate and relevant in emergency contexts. The primary aim of this assignment was therefore to explore whether it is considered appropriate to apply the existing evidence base for WASH interventions to support emergency operations as it stands and, if not, to consider what activities may be required to improve the evidence base. -

A Sewer Catastrophe Companion

A SEWER CATASTROPHE COMPANION Dry Toilets for Wet Disasters EMERGENCY The year is 20__. The Juan de Fuca tectonic plate has shifted, causing an earthquake with a magnitude of 9.0, devastating the Pacific Northwest. Underground infrastructure has shaken. Sewers are broken and leaking into waterways. You have food and water, your house is still habitable, and your friends and fam- ily are all accounted for. Finally, you can slow down and take stock. You need to poop. Where will you go? RESPONSE This guide presents a toilet system that you can do yourself without relying on a co- ordinated and timely response by someone else. This system served after earthquakes destroyed sanitation systems in Haiti and New Zealand. This guide is for planning ahead and preparing kits, whether for yourself, your household, your apartment building, or your block. This flexible system is built around ubiquitous and freely available 5-gallon buckets. A solution for today that’s Urine itself is sterile, it can be applied to not a problem for tomor- land, dramatically reducing the amount of row. 1. Pee in Bucket material handling. After the earthquake in New Zealand, 2. Poop in Bucket people used separate toilets for poop and pee to reduces material handling, disease risks, and work. Washing hands is fundamental. We de- 3. Wash Hands signed a simple, efficient, and ergonomic portable sink using buckets. A solution for managing Store materials until they can be properly excreta that’s not excreting 1. Cap and processed and treated. This allows time for problems later. an official response and pickup, or to build Store your own compost processing area. -

EMERGENCY WATER SUPPLY GUIDEBOOK for Commercial, Industrial and Institutional Facilities

EMERGENCY WATER SUPPLY GUIDEBOOK For Commercial, Industrial and Institutional Facilities ©LANE PREPAREDNESS COALITION 2016 PAGE 0 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS SUBJECT MATTER EXPERTS This guidebook was written and Many thanks to these volunteers reviewed by Lane Preparedness and their agencies for their work Coalition (LPC) Members who are writing and reviewing this guide. experts in the fields of water supply and distribution, plumbing code, water Project Team Members quality and facility operations. Dr. Geoff Simmons, MD (retired) This guide touches on water supply considerations during a disaster and Harlan Coats, Eugene School District 4J recovery. The intent is to provide Jamie Porter PE, Rainbow Water District general information as a starting point for this important aspect of business Jill Hoyenga, LPC Convener continuity planning. This guide is not meant to replace staff expertise or Laura Farthing PE, Eugene Water & consultation with a professional Electric Board regarding the unique attributes of your Mark Walker, McKenzie Willamette agency or facility. Hospital EUGENE-SPRINGFIELD NATURAL Rob Hallett, City of Eugene HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN Sarah Puls, Lane County Public Health This guide has been produced under the care of the LPC Natural Hazard Steve Graham, City of Springfield Mitigation Plan Sub-Committee. In the 2015 plan, emergency water supply Teresa Kennedy, City of Eugene was called out as a critical need that Thomas Price, SHE had not yet been adequately addressed by our community. This Karen Edmonds, Food for Lane County guide was written to answer to the need for guidance about how Patrick Lowen, Market of Choice businesses can include emergency water supply into their business continuity plans. -

Communicable Disease Control in Emergencies: a Field Manual Edited by M

Communicable disease control in emergencies A field manual Communicable disease control in emergencies A field manual Edited by M.A. Connolly WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Communicable disease control in emergencies: a field manual edited by M. A. Connolly. 1.Communicable disease control–methods 2.Emergencies 3.Disease outbreaks–prevention and control 4.Manuals I.Connolly, Máire A. ISBN 92 4 154616 6 (NLM Classification: WA 110) WHO/CDS/2005.27 © World Health Organization, 2005 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the pert of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on map represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify he information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising in its use. -

Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion

Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion Andy Bastable and Lucy Russell, Oxfam GB July 2013 The HIF is supported by The HIF is managed by Contents i Acronyms ii Executive Summary 1 Background 2 Methodology 3 Literature Review Consultation Findings 5 Focus Group Discussions with Beneficiaries 5 Workshops and Discussions at Country or Sub-Country Level 6 Online Practitioner Survey 8 Global WASH Cluster 9 Donor responses to the Questionnaire 10 Consultation findings and discussion 12 of priority gaps Annex 1: Terms of Reference 15 Annex 2: Timeline 16 Annex 3: List of issues raised by each stakeholder group in order of priority 17 Annex 4: Detailed Results from the Literature Review 19 Annex 5: Literature Review References 20 Annex 6: Profile of Online Practitioner Survey Respondents 21 Annex 7: Online Gap Analysis Survey for WASH Practitioners 22 Annex 8: Summary of ‘Other’ Issues raised 25 Annex 9: Detailed Results from Donor Questionnaire 28 Gap Analysis in Emergency Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion Acronyms ACF Action Contre la Faim ALNAP Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance CARE Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere CHAST Children’s Hygiene and Sanitation Training CLTS Community Led Total Sanitation CRS Catholic Relief Services DRR Disaster Risk Reduction DFID Department for International Development (UK) DRC Democratic Republic of Congo DWS Drinking Water Supply ECHO Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection department of the European Commission ELRHA Enhancing Learning and -

Practical Paper Esos® – Emergency Sanitation Operation System D

156 Practical Paper © IWA Publishing 2015 Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development | 05.1 | 2015 Practical Paper eSOS® – emergency Sanitation Operation System D. Brdjanovic, F. Zakaria, P. M. Mawioo, H. A. Garcia, C. M. Hooijmans, J. C´ urko, Y. P. Thye and T. Setiadi ABSTRACT This paper presents the innovative emergency Sanitation Operation System (eSOS) concept created D. Brdjanovic (corresponding author) F. Zakaria to improve the entire emergency sanitation chain and provide decent sanitation to people in need. P. M. Mawioo H. A. Garcia The eSOS kit is described including its components: eSOS smart toilets, an intelligent excreta C. M. Hooijmans Environmental Engineering and Water Technology collection vehicle-tracking system, a decentralized excreta treatment facility, an emergency Department, UNESCO-IHE, sanitation coordination center, and an integrated eSOS communication and management system. P.O. Box 3015, 2601 DA Delft, The Netherlands The paper further deals with costs and the eSOS business model, its challenges, applicability and E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] relevance. The first application, currently taking place in the Philippines will bring valuable insights on D. Brdjanovic the future of the eSOS smart toilet. It is expected that eSOS will bring changes to traditional disaster Faculty of Applied Sciences, Department of Biotechnology, relief management. Delft University of Technology, Key words | emergency, feces, sanitation, technology, toilet, urine Julianalaan 67, 2628 BC Delft, The Netherlands J. Curko Faculty of Food Technology and Biotechnology, University of Zagreb, Pierottijeva 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Y. P. Thye T. Setiadi Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Industrial Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. -

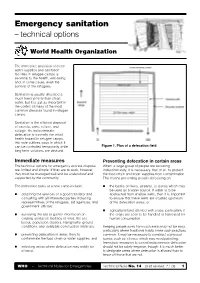

Emergency Sanitation – Technical Options

Emergency sanitation – technical options World Health Organization The immediate provision of clean water supplies and sanitation facilities in refugee camps is essential to the health, well-being and, in some cases, even the survival of the refugees. Sanitation is usually allocated a much lower priority than clean water, but it is just as important in the control of many of the most common diseases found in refugee camps. Sanitation is the efficient disposal of excreta, urine, refuse, and sullage. As indiscriminate defecation is normally the initial health hazard in refugee camps, this note outlines ways in which it can be controlled temporarily while Figure 1. Plan of a defecation field long-term solutions are devised. Immediate measures Preventing defecation in certain areas The technical options for emergency excreta disposal When a large group of people are excreting are limited and simple. If they are to work, however, indiscriminately, it is necessary, first of all, to protect they must be managed well and be understood and the food-chain and water supplies from contamination. supported by the community. This means preventing people defecating on: The immediate tasks at a new camp include: the banks of rivers, streams, or ponds which may be used as a water source. If water is to be obtaining the services of a good translator and abstracted from shallow wells, then it is important consulting with all interested parties including to ensure that these wells are situated upstream representatives of the refugees, aid agencies, and of the defecation areas; or government officials; agricultural land planted with crops, particularly if surveying the site to gather information on the crops are soon to be handled or harvested for existing sanitation facilities (if any), the site human consumption. -

Emergency Sanitation the Loss of Clean Running Water Or Loss of A

Emergency Sanitation The loss of clean running water or loss of a functional sewer system after a disaster can dramatically increase the chances of diarrheal diseases and outbreaks. Just one gram of human feces may have 100 parasite eggs, 1,000 parasite cysts, 1 million bacteria, and as many as 10 million viruses! With this risk all around us, it underscores the importance of staying clean and disposing of human and other waste properly after a disaster. Pathogens that may present a risk after a disaster include Escherichia Coli (E. Coli), Leptospirosis, hepatitis A, norovirus, and in some situations Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella enterica. Exposure to disease causing pathogens may occur as a result of contaminated water, sharing of water containers and cooking equipment, or the loss of basic sanitation such as the ability to wash hands thoroughly. Even brushing your teeth with water that is not safe for consumption can result in exposure to pathogens. Avoiding exposure to these pathogens starts with a careful assessment of water quality following a disaster. Because municipal water lines run parallel to sewer lines, even a small break in both lines can result in cross-contamination. Follow guidance from local officials on use of municipal water following a disaster (e.g., shutting off water to house, treating water before use, or flushing system). Once a reliable, clean water source has been established, emphasis should be placed on two key priorities: a) providing a mechanism for personal hygiene and handwashing and b) managing human waste. Personal Hygiene and Handwashing Any questionable tap water used for drinking and personal hygiene (hand-washing, brushing teeth) must be boiled or otherwise disinfected. -

Innovations in Emergency Sanitation

Innovations in emergency sanitation 2 day workshop, 11-13 February 2009, Stoutenburg, The Netherlands + = ? Urine diverting pedestal Green Oxfam latrine Photo: Duncan Mara. slabs. Photo: RedR Organised by: Oxfam GB, IWA, GTZ, WASTE Minutes by: Cecilia Ruberto, WASTE and Åse Johannessen, IWA 1 Participants Daudi Bikaba PHE Advisor Oxfam UK Andy Bastable Head of water and sanitation Oxfam UK Gert de Bruijne Eco San Expert WASTE NL Niels Lenderink Adviser WASTE NL Arne Panesar GTZ Germany Libertad Gonzalez Watsan Unit IFRC Switzerland Vincent Taillandier Water & Sanitation Adviser ACF France Karine Deniel Water & Sanitation Adviser ACH Spain Joos Van den Noortgate Watsan Advisor MSF Belgium Ase Johannessen Development Programme Officer IWA NL Paul Shanahan Emergency WASH sector specialist CARE Australia Brian Mathew Watsan consultant Independent UK Ron Sawyer Director SARAR Mexico Peter van Luttervelt Social architect Coram NL Femke Hoekstra Program assistant RUAF ETC NL Cecilia Ruberto Intern WASTE NL Toby Gould Cluster Projects Coordinator RedR UK Contents Day 1 Thursday 12/02/2009 0. Introduction 1. Individual Expectations 2. Presentations 2.1 “The Toilet Challenge” - Andy Bastable, Oxfam UK 2.2 “Emergency Sanitation” - Libertad Gonzalez, IFRC 2.3 “Disability and Sanitation” - Vincent Taillandier, ACF F 2.4 “Children sanitation in emergencies” - Karine Deniel, ACF E 2.5 “Decision Support Tool” - Gert de Bruijne, WASTE 2.6 “Eco San for emergencies” - Brian Mathew, independent 2.7 “Ecosan in Emergency and Reconstruction” - Daudi Bikaba, Oxfam UK 2.8 “San-Accessories – Emergency workshop” - Ron Sawyer, SARAR 2.9 “Linking relief, rehabilitation and development – a role for urban agriculture?”- Femke Hoekstra, ETC 3. Viewing of the film: “The Human Excreta” Day 2 Friday 13/02/2009 4. -

UNICEF Angola Humanitarian Situation Report

UNICEF ANGOLA SITUATION REPORT - October 2016 ANGOLA Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEF/UN023868/Clark SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 18 million • People vaccinated for Yellow Fever An estimated 1.42 million people (756,000 children) are affected by the drought, including 800,000 people food insecure in the provinces of Cunene, Namibe and Huila. 1.42 million • In 2016, the estimated caseload of children with severe acute malnutrition People affected by drought (SAM) in the 7 most affected provinces is 95,877, with 44,511 cases registered in the Provinces of Huila, Cunene and Namibe. 756,000 • Over 11,513 children under five with SAM have been treated through Children affected by drought therapeutic treatment programmes assisted by UNICEF in 2016. • UNICEF has reached 24,000 people with access to safe water through the rehabilitation of 38 water pumps in 2016. 95,877 • UNICEF in partnership with Red Cross Angola reached more than 320,000 Children with SAM in the 7 most drought people with house to house visits, mass media and social mobilization affected provinces during the fifth phase of the Yellow Fever vaccination campaign targeting 8 priority districts in 6 provinces • 44,511 More than 18 million people (6 months and older) have been vaccinated for Children with SAM in the 3 most drought Yellow Fever in 14 provinces and UNICEF is currently procuring 3 million affected provinces additional doses of vaccines. 11,513 Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs Children U5 with SAM treated through Severe droughts are affecting 7 provinces (Cunene, Huila, Namibe, Benguela, therapeutic treatment programmes assisted Cuando Cubango, Cuanza Sul and Huambo). -

WASH Cluster Sanitation Technical Working Group Guidelines for Household Level Sanitation Updated October 2019

WASH Cluster Sanitation Technical Working Group Guidelines for Household Level Sanitation Updated October 2019 Context The Government of Mozambique aim is to eliminate the practice of open defecation across the country by 2025 and universal access to basic sanitation by 2030. It has been done through the mass mobilization of communities on behavioral change messages, certifying open defecation free communities, and strengthening sanitation markets. Prior to the cyclones Kenneth and Idai, the rate of open defecation in the rural areas has been high across the affected provinces Sofala (67%), Manica (45%) and Zambezia (72%). This means that even households not directly impacted by the cyclone or floods, have a high probability of practicing open defecation. The two cyclones that affected Mozambique, Idai and Kenneth, have had a profound impact on the population and the access to sanitation infrastructures. Two main affected groups can be recognized; the people resettled in new rural areas (“resettlement sites”), and the generally affected population by cyclonic winds and/or floods. The first group can be categorized as the most vulnerable, followed by the generally affected area that remained in their habitual place of residence. Sanitation interventions for relocation centers and first phase emergency support in resettlement sites focused on the construction of temporary emergency communal latrines. The guidelines for this sanitation support is included in the Mozambique WASH Cluster Emergency Sanitation Guidelines1. Their construction was often undertaken by humanitarian agencies, where materials, and sometimes labor, were fully subsidized. After the acute emergency needs for construction of latrines for communal latrines for 1:5 households the WASH Cluster will support the construction of household latrines in resettlement sites and affected communities using a dome slab modality to improve sanitation access and to encourage improved hygiene behaviors. -

Communicable Disease Control in Emergencies: a Field Manual Edited by M

Communicable disease control in emergencies A field manual Edited by M.A. Connolly WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Communicable disease control in emergencies: a field manual edited by M. A. Connolly. 1.Communicable disease control–methods 2.Emergencies 3.Disease outbreak, prevention and control 4.Manuals I.Connolly, Máire A. ISBN 92 4 154616 6 (NLM Classification: WA 110) WHO/CDS/2005.27 © World Health Organization, 2005 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the pert of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on map represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify he information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World