No Enemies to the Left

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

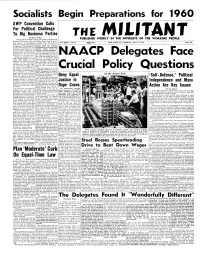

Socialists Begin Preparations for 1960

Socialists Begin Preparations for 1960 SWP Convention Calls For Political Challenge To Big Business Parties By M urry Weiss The Socialist Workers Party concluded its Eighteenth National Convention last week after three days of inten sive work in an atmosphere charged with self-confident realism and revolutionary social- ist optimism. The participation election which the resolution of some 250 delegates and visi characterized "as the next major tors from every branch in the political action" facing the country marked a high point for American socialist movement. the party since the 1946 Chicago While some intensification of Convention on the eve of the the class struggle as a result of cold-war and witch-hunt period. the capitalist offensive against the living standards of the work NAACP Delegates Face Among the delegates was a large representation of youth ers is to be expected, Dobbs held that “we cannot bank on along with founders of the American communist movement, any immediate change in the veterans of the trade-union mass movement” in 1959 in time movement and front-line fight to make a labor party develop m ent in 1960 a practical possibility ers in the Negro struggle. Thus, . the vitality and continuity of Thus the urgent task in the the Marxist movement in the presidential elections is to in Crucial Policy Questions United States was personified in tensify propaganda for indepen the convention by socialists dent political action as an al whose records go back to the ternative to continued support IWW, the pre-1917 Socialist At the Soviet Fair of the Democratic Party. -

PATTERSON, William

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 PATTERSON, William MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "PATTERSON, William" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 152. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/152 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCOPE NOTE The papers of William Lorenzo Patterson (1891-1980), often known as “Mr. Civil Rights,” document the life of the noted political activist, lawyer, orator, organizer, writer and Communist from San Francisco. The papers, which contain correspondence, printed materials, writings, and clippings, span the years 1919-1979. The bulk of the material covers the mid-1950s through 1979 when Patterson lived in New York. The collection measures approximately 15.5 linear feet and mostly highlights Patterson's political activism. His professional career as a lawyer can be analyzed through various cases he worked on through the Communist Party U.S.A. and the International Labor Defense. A view into his personal life can be obtained through his diaries and birthday tributes, as well as in the drafts and galleys of his autobiography, The Man Who Cried Genocide: An Autobiography. Correspondence with his third wife, Louise Thompson Patterson, their daughter, Mary Lou, and fellow activist leaders gives insight into some personal and political beliefs of Patterson, as do his writings on race relations, social injustices and the political activism of various individuals and organizations. -

October 14, 1976 I Yol.Xll, No

-v who liked our music a lot and some who new album (and other alternative didn't tike it at ¿ll) and after struggling a.lbums). Their letters tell incredible life with the question of oubeach vs. slories, sharing their eicitement, their compromise among ourselves, we fear, their discoveries, their risks. Being decided to do ourthird album on Red- a small company, they figured I might wood, once again. I am telieved that I'm gettheirletters. And I dol There is the not having to deal with the pressure of joy that must match the disappointment the industry but I'm sad when I think of in nof reaching all the women who don't all the people who don't have (oreven have access to an FM radio or altetnative October 14, 1976 I Yol.Xll, No. 34 know about) any optigns. So they watch concerts or womens' records etc. Alice Coopei whip a woman in one of his Right now Redwood Records is only on shocking displays recently performed on the distributing arm for the records and 4. Continental Walk Converges certainly bad news the Billboard Rock Music Awards. songbooks produced to date. We are not Washington / Crace Hedemann for the Portuguese Undet current conditions "energizing- working class, since it means, atbest, capital" can only be accomplishedby How are we going to get options to going to do any new things fot a while. and Murray Rosenblith But we hope that you will continue to the maintenance of the status quo. How- speedups, cutting real'rvages and people? Some people ate working within 6. -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Riding to Freedom, the New Secession

.THE NEW SECESSION -AND HOW TO SMASH IT Riding to Freedom Herbert Aptheker * James E. Jackson 10 cent.s ~ ( 6 5/o Is- ABOUT THE AUTHORS RIDING TO FREEDOM JAMES E. JACKSON has, since the early thirties, been a prominent figure in the democratic struggles of the workers and Negro people of the South. By Herbert Aptheker He was a militant student leader and organizer of the Southern youth movement, and later an organizer among the auto workers of Michigan. He is presently the Editor of The Worker. THE MONSTROUS ASSAULTS by COW the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citi ardly gangsters and racists upon un zens' Councils and the John Bi rch HERBERT APTHEKER is the Editor of the Marxist monthly, Political armed and non-resisting young men Society, are actual conspirators in ex A ffairs, and widely known as a scholar, historian, educator and lecturer. H e and women in Alabama late in May actly the same way as the Old Se is the author of several major works including American Negro Slave Re is the culminating act of a pre-con cessionists, with their Knights of the volts, History and Reality, The Truth About H ungary and Toward Negro certed insurrectionary movement. Golden Circle, and their White Ca Freedom. His latest books, The Colonial Era and The American Revolu Earlier scenes were played out in melia Societies, maliciously plotted Florida, in Virginia, in Arkansas, the destruction of the Republic and tion: 1763-1783, are the first in a multi-volumed history of the United States. in Mississippi, in Louisiana. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Morris Childs Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf896nb2v4 No online items Register of the Morris Childs papers Finding aid prepared by Lora Soroka and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1999 Register of the Morris Childs 98069 1 papers Title: Morris Childs papers Date (inclusive): 1924-1995 Collection Number: 98069 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English and Russian Physical Description: 2 manuscript boxes, 35 microfilm reels(4.3 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, reports, notes, speeches and writings, and interview transcripts relating to Federal Bureau of Investigation surveillance of the Communist Party, and the relationship between the Communist Party of the United States and the Soviet communist party and government. Includes some papers of John Barron used as research material for his book Operation Solo: The FBI's Man in the Kremlin (Washington, D.C., 1996). Hard-copy material also available on microfilm (2 reels). Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Childs, Morris, 1902-1991. Contributor: Barron, John, 1930-2005. Location of Original Materials J. Edgar Hoover Foundation (in part). Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items, computer media, and digital files. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos, films, or digital files during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all material is immediately accessible. -

The Negro People and the Soviet Union

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1950 The Negro people and the Soviet Union Paul Robeson Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Robeson, Paul, "The Negro people and the Soviet Union" (1950). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 25. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/25 Th'e NEGRO PEOPLE .- - .- .. - MOM THE AUTHOR PAUL ROBESON is one of the foremost lead- ers of the Negro people and a concut artist of wdrenown. He has been chairman of the Cour#il on African Maim since the formation of ktvital organization 12 years aga In the summer of 1949 he returd from a four-month speaking and concert tour which took this beloved spokesman of the Negro pple to eight countries of Europe, including the Soviet Union. Whik in . Europe he participated as an honored yest in the celebration of the Pushkin centennial anniversary in MOSCOW,and in the World Peace Gmgrcss in gg:m A world-wide storm of indigoation greeted the + 3~rm-~pattacks upon him at PdcskU, N. v. Zhatnctofthispamphfetisanaddmjdefiv- 'aed by Mr. Robeson at a banquet spodby .- I& National Council of AmericanMct Friend* - ship u the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in New Yark, tm November 10, 1949, on the occasion of tht debration of the 32nd anniv~of the SaPiet Union. -

Marxists and the Churches in Yugoslavia

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 3 3-1984 Marxists and the Churches in Yugoslavia Paul Mojzes Rosemont College, Rosemont, PA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mojzes, Paul (1984) "Marxists and the Churches in Yugoslavia," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol4/iss2/3 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARXISTS AND THE CHURCHES IN YUGOSLAVIA by Paul Mojzes Paul Mojzes (United Methodist) was born and educated in Yugoslavia where he had two years of Law School at Belgrade University before moving to the United States wh ere he received the A. B. degree from Florida Southern College and Ph. D. in church history with ernphasis on · Eastern Europe from Boston University. He is professor of religious studies at Rosemont College and the writer of numerous studies on Eastern Europe. He is one of the; vice chairpersons of CAREE and the editor of OPREE. He has frequently visited Eastern Europe, especially Yugoslavia. A. Purpose The purpose of this article is to present the relationship between religion and Marxism in Yugoslavia. For practical purposes the term religion will be identified in this paper with institutional religion, namely Christian Churches and to a lesser degree Islam while the term Marxism will coincide with Yugoslav Communism. -

NAT TURNER's REVOLT: REBELLION and RESPONSE in SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory

NAT TURNER’S REVOLT: REBELLION AND RESPONSE IN SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory M. Thomas) ABSTRACT In 1831, Nat Turner led a revolt in Southampton County, Virginia. The revolt itself lasted little more than a day before it was suppressed by whites from the area. Many people died during the revolt, including the largest number of white casualties in any single slave revolt in the history of the United States. After the revolt was suppressed, Nat Turner himself remained at-large for more than two months. When he was captured, Nat Turner was interviewed by whites and this confession was eventually published by a local lawyer, Thomas R. Gray. Because of the number of whites killed and the remarkable nature of the Confessions, the revolt has remained the most prominent revolt in American history. Despite the prominence of the revolt, no full length critical history of the revolt has been written since 1937. This dissertation presents a new history of the revolt, paying careful attention to the dynamic of the revolt itself and what the revolt suggests about authority and power in Southampton County. The revolt was a challenge to the power of the slaveholders, but the crisis that ensued revealed many other deep divisions within Southampton’s society. Rebels who challenged white authority did not win universal support from the local slaves, suggesting that disagreements within the black community existed about how they should respond to the oppression of slavery. At the same time, the crisis following the rebellion revealed divisions within white society. -

USA and RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman THE COMMUNIST PARTY USA AND RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman THE COMMUNIST PARTY, USA, AND RADICAL ORGANIZATIONS, 1953-1960 FBI Reports from the Eisenhower Library Project Coordinator and Guide Compiled by Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Communist Party, USA, and radical organizations, 1953-1960 [microform]: FBI reports from the Eisenhower Library / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. - (Research collections in American radicalism) Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Robert E. Lester. ISBN 1-55655-195-9 (microfilm) 1. Communism-United States--History--Sources--Bibltography-- Microform catalogs. 2. Communist Party of the United States of America~History~Sources~Bibliography~Microform catalogs. 3. Radicalism-United States-History-Sources-Bibliography-- Microform catalogs. 4. United States-Politics and government-1953-1961 -Sources-Bibliography-Microform catalogs. 5. Microforms-Catalogs. I. Lester, Robert. II. Communist Party of the United States of America. III. United States. Federal Bureau of Investigation. IV. Series. [HX83] 324.27375~dc20 92-14064 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the White House Office, Office of the Special Assistant for National Security Affairs in the custody of the Eisenhower Library, National Archives and Records Administration. -

The Color of History Stan Isaacs

BOOK REVIEWS The Color of History Stan Isaacs Out of Left Field: demeaning comedy shticks that inspired hiring Jackie Robinson, first for their Jews and Black Baseball the white press to depict him as a shuffling, Montreal farm team and then unveil lazy black man. Gottlieb felt he was provid ing him as a Dodger in 1947. Agitation Rebecca T. Alpert ing good work for a number of men who in the black press to breach the color Oxford University Press, would otherwise be “bell hopping or mop line started as early as the 1920s. Jew 2011, $27.95, pp. 272 ping floors.” He and Saperstein ignored the ish reporter Lester Rodney of The Daily complaints of critics who thought comedy Worker joined the fight inthemid-1930s, baseball was a throwback to black-face min and together they kept the issue alive in In Out of Left Field, Rebecca Alpert describes strel traditions and detrimental to the race. one form or another until the Dodgers the role of Jews in promoting professional Because Gottlieb and Saperstein were general manager, Branch Rickey, took black baseball and efforts by Jewish com Jewish, this led to some anti-Jewish stereo the bold step of defying fellow owners munist sportswriters to break the color to sign Robinson. line in major league baseball. Alpert, There were other factors. World War who teaches religion and women’s stud II emphasized the hypocrisy of blacks ies at Temple University, solidly estab fighting for their country but not being lishes the important—and sometimes allowed to play in the so-called national controversial—place of Jewish pro pastime.