Classical Others. Anthropologies of Antiquity1 Johannes Siapkas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Download The

THE CONCEPT OF SACRED WAR IN ANCIENT GREECE By FRANCES ANNE SKOCZYLAS B.A., McGill University, 1985 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classics) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1987 ® Frances Anne Skoczylas, 1987 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of CLASSICS The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date AUtt-UST 5r 1Q87 ii ABSTRACT This thesis will trace the origin and development of the term "Sacred War" in the corpus of extant Greek literature. This term has been commonly applied by modern scholars to four wars which took place in ancient Greece between- the sixth and fourth centuries B. C. The modern use of "the attribute "Sacred War" to refer to these four wars in particular raises two questions. First, did the ancient historians give all four of these wars the title "Sacred War?" And second, what justified the use of this title only for certain conflicts? In order to resolve the first of these questions, it is necessary to examine in what terms the ancient historians referred to these wars. -

Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire by David Graeber

POSSIBILITIES Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire POSSIBILITIES Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire David Graeber Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire by David Graeber ISBN 978-1904859-66-6 Library of Congress Number: 2007928387 ©2007 David Graeber This edition © 2007 AK Press Cover Design: John Yates Layout: C. Weigl & Z. Blue Proofreader: David Brazil AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612 www.akpress.org akpress @akpress.org 510.208.1700 AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh EH8 9YE www.akuk.com [email protected] 0131.555.5165 Printed in Canada on 100% recycled, acid-free paper by union labor. TABLE OF CONTENTS In tro d u c tio n ....................................................................................................................... 1 PART I: SOME THOUGHTS ON THE ORIGINS OF OUR CURRENT PREDICAMENT 1 Manners, Deference, and Private Property: Or, Elements for a General Theory of Hierarchy................................................................................................... 13 2 The Very Idea of Consumption: Desire, Phantasms, and the Aesthetics of Destruction from Medieval Times to the Present...............................................57 3 Turning Modes of Production Inside-Out: Or, Why Capitalism Is a Transformation of Slavery (short version).......................................................... 85 4 Fetishism as Social Creativity: Or, Fetishes Are Gods in the Process of C onstruction.................................................................................................................113 -

The Classicism of Hugh Trevor-Roper

1 THE CLASSICISM OF HUGH TREVOR-ROPER S. J. V. Malloch* University of Nottingham, U.K. Abstract Hugh Trevor-Roper was educated as a classicist until he transferred to history, in which he made his reputation, after two years at Oxford. His schooling engendered in him a classicism which was characterised by a love of classical literature and style, but rested on a repudiation of the philological tradition in classical studies. This reaction helps to explain his change of intellectual career; his classicism, however, endured: it influenced his mature conception of the practice of historical studies, and can be traced throughout his life. This essay explores a neglected aspect of Trevor- Roper’s intellectual biography through his ‘Apologia transfugae’ (1973), which explains his rationale for abandoning classics, and published and unpublished writings attesting to his classicism, especially his first publication ‘Homer unmasked!’ (1936) and his wartime notebooks. I When the young Hugh Trevor-Roper expressed a preference for specialising in mathematics in the sixth form at Charterhouse, Frank Fletcher, the headmaster, told him curtly that ‘clever boys read classics’.1 The passion that he had already developed for Homer in the under sixth form spread to other Greek and Roman authors. In his final year at school he won two classical prizes and a scholarship that took him in 1932 to Christ Church, Oxford, to read classics, literae humaniores, then the most * Department of Classics, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD. It was only by chance that I developed an interest in Hugh Trevor-Roper: in 2010 I happened upon his Letters from Oxford in a London bookstore and, reading them on the train home, was captivated by the world they evoked and the style of their composition. -

DEMOPOLIS Democracy Before Liberalism in Theory and Practice

Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 DEMOPOLIS Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice JOSIAH OBER Stanford University, California v Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 Contents List of Figures page xi List of Tables xii Preface: Democracy before Liberalism xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on the Text xix 1 Basic Democracy 1 1.1 Political Theory 1 1.2 Why before Liberalism? 5 1.3 Normative Theory, Positive Theory, History 11 1.4 Sketch of the Argument 14 2 The Meaning of Democracy in Classical Athens 18 2.1 Athenian Political History 19 2.2 Original Greek Defnition 22 2.3 Mature Greek Defnition 29 3 Founding Demopolis 34 3.1 Founders and the Ends of the State 36 3.2 Authority and Citizenship 44 3.3 Participation 48 3.4 Legislation 50 3.5 Entrenchment 52 3.6 Exit, Entrance, Assent 54 3.7 Naming the Regime 57 4 Legitimacy and Civic Education 59 4.1 Material Goods and Democratic Goods 60 4.2 Limited-Access States 63 4.3 Hobbes’s Challenge 64 4.4 Civic Education 71 ix Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 x Contents 5 Human Capacities and Civic Participation 77 5.1 Sociability 79 5.2 Rationality 83 5.3 Communication 87 5.4 Exercise of Capacities as a Democratic Good 88 5.5 Free Exercise and Participatory Citizenship 93 5.6 From Capacities to Security and Prosperity 98 6 Civic Dignity -

Politics and Policy in Corinth 421-336 B.C. Dissertation

POLITICS AND POLICY IN CORINTH 421-336 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by DONALD KAGAN, B.A., A.M. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by: Adviser Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ................................................. 1 CHAPTER I THE LEGACY OF ARCHAIC C O R I N T H ....................7 II CORINTHIAN DIPLOMACY AFTER THE PEACE OF NICIAS . 31 III THE DECLINE OF CORINTHIAN P O W E R .................58 IV REVOLUTION AND UNION WITH ARGOS , ................ 78 V ARISTOCRACY, TYRANNY AND THE END OF CORINTHIAN INDEPENDENCE ............... 100 APPENDIXES .............................................. 135 INDEX OF PERSONAL N A M E S ................................. 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................... 145 AUTOBIOGRAPHY ........................................... 149 11 FOREWORD When one considers the important role played by Corinth in Greek affairs from the earliest times to the end of Greek freedom it is remarkable to note the paucity of monographic literature on this key city. This is particular ly true for the classical period wnere the sources are few and scattered. For the archaic period the situation has been somewhat better. One of the first attempts toward the study of Corinthian 1 history was made in 1876 by Ernst Curtius. This brief art icle had no pretensions to a thorough investigation of the subject, merely suggesting lines of inquiry and stressing the importance of numisihatic evidence. A contribution of 2 similar score was undertaken by Erich Wilisch in a brief discussion suggesting some of the problems and possible solutions. This was followed by a second brief discussion 3 by the same author. -

A History of the Scholarship on the Seisachtheia Of

A HISTORY OF THE SCHOLARSHIP ON THE SEISACHTHEIA OF SOLON By William Findiay B.A., McGill University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classical, Near Eastern and Religious Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July 1999 ©William Findiay, 1999 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis surveys the scholarship on the seisachtheia of Solon from the nineteenth century to the present. The scholars included in the survey are, in ap• proximate chronological order: George Grote, G.F. Schomann, Ernst Curtius, Friedrich Engels, Fustel de Coulanges, Paul Guiraud, Ulrich von Wilamowitz- Moellendorff, Ludovic Beauchet, Heinrich Swoboda, Charles Gilliard, Georg Busolt, Karl Julius Beloch, William John Woodhouse, Kurt von Fritz, Naphtali Lewis, John V.A. Fine, A. French, Detlef Lotze, N.G.L. Hammond, Edouard Will, Giovanni Ferrara, Filippo Cassola, Agostino Masaracchia, David Asheri, Stefan Link, P.J. Rhodes, and Terry Buckley. -

Roman Population Size: the Logic of the Debate

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Roman population size: the logic of the debate Version 2.0 July 2007 Walter Scheidel Stanford University Abstract: This paper provides a critical assessment of the current state of the debate about the number of Roman citizens and the size of the population of Roman Italy. Rather than trying to make a case for a particular reading of the evidence, it aims to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of rival approaches and examine the validity of existing arguments and critiques. After a brief survey of the evidence and the principal positions of modern scholarship, it focuses on a number of salient issues such as urbanization, military service, labor markets, political stability, living standards, and carrying capacity, and considers the significance of field surveys and comparative demographic evidence. © Walter Scheidel. [email protected] 1 1. Roman population size: why it matters Our ignorance of ancient population numbers is one of the biggest obstacles to our understanding of Roman history. After generations of prolific scholarship, we still do not know how many people inhabited Roman Italy and the Mediterranean at any given point in time. When I say ‘we do not know’ I do not simply mean that we lack numbers that are both precise and safely known to be accurate: that would surely be an unreasonably high standard to apply to any pre-modern society. What I mean is that even the appropriate order of magnitude remains a matter of intense dispute. This uncertainty profoundly affects modern reconstructions of Roman history in two ways. First of all, our estimates of overall Italian population number are to a large extent a direct function of our views on the size of the Roman citizenry, and inevitably shape any broader guesses concerning the demography of the Roman empire as a whole. -

The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE

Foundations of History: The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE by Zachary B. Hallock A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, Chair Associate Professor Benjamin Fortson Assistant Professor Brendan Haug Professor Nicola Terrenato Zachary B. Hallock [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0337-0181 © 2018 by Zachary B. Hallock To my parents for their endless love and support ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Rackham Graduate School and the Departments of Classics and History for providing me with the resources and support that made my time as a graduate student comfortable and enjoyable. I would also like to express my gratitude to the professors of these departments who made themselves and their expertise abundantly available. Their mentoring and guidance proved invaluable and have shaped my approach to solving the problems of the past. I am an immensely better thinker and teacher through their efforts. I would also like to express my appreciation to my committee, whose diligence and attention made this project possible. I will be forever in their debt for the time they committed to reading and discussing my work. I would particularly like to thank my chair, David Potter, who has acted as a mentor and guide throughout my time at Michigan and has had the greatest role in making me the scholar that I am today. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Andrea, who has been and will always be my greatest interlocutor. -

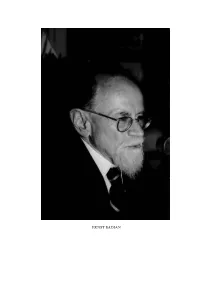

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

A Companion to the Classical Greek World

A COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL GREEK WORLD Edited by Konrad H. Kinzl A COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL GREEK WORLD BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of periods of ancient history, genres of classical literature, and the most important themes in ancient culture. Each volume comprises between twenty-five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. ANCIENT HISTORY Published A Companion to Greek Rhetoric Edited by Ian Worthington A Companion to Roman Rhetoric Edited by William J. Dominik and Jonathan Hall A Companion to Classical Tradition Edited by Craig Kallendorf A Companion to the Roman Empire Edited by David S. Potter A Companion to the Classical Greek World Edited by Konrad H. Kinzl A Companion to the Ancient Near East Edited by Daniel C. Snell A Companion to the Hellenistic World Edited by Andrew Erskine In preparation A Companion to the Archaic Greek World Edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Hans van Wees A Companion to the Roman Republic Edited by Nathan Rosenstein and Robert Morstein-Marx A Companion to the Roman Army Edited by Paul Erdkamp A Companion to Byzantium Edited by Elizabeth James A Companion to Late Antiquity Edited by Philip Rousseau LITERATURE AND CULTURE Published A Companion to Ancient Epic Edited by John Miles Foley A Companion to Greek Tragedy Edited by Justina Gregory A Companion to Latin Literature Edited by Stephen Harrison In Preparation A Companion to Classical Mythology Edited by Ken Dowden A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography Edited by John Marincola A Companion to Greek Religion Edited by Daniel Ogden A Companion to Roman Religion Edited by Jo¨rg Ru¨pke A COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL GREEK WORLD Edited by Konrad H. -

The World of Odysseus M

THE WORLD OF ODYSSEUS M. I. FINLEY INTRODUCTION BY BERNARD KNOX NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS CLASSICS THE WORLD OF ODYSSEUS M. I. FINLEY (1912–1986), the son of Nathan Finkelstein and Anna Katzellenbogen, was born in New York City. He graduated from Syracuse University at the age of fifteen and received an MA in public law from Columbia, before turning to the study of ancient history. During the Thirties Finley taught at Columbia and City College and developed an interest in the sociology of the ancient world that was shaped in part by his association with members of the Frankfurt School who were working in exile in America. In 1952, when he was teaching at Rutgers, Finley was summoned before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee and asked whether he had ever been a member of the Communist Party. He refused to answer, invoking the Fifth Amendment; by the end of the year he had been fired from the university by a unanimous vote of its trustees. Unable to find work in the US, Finley moved to England, where he taught for many years at Cambridge, helping to redirect the focus of classical education from a narrow emphasis on philology to a wider concern with culture, economics, and society. He became a British subject in 1962 and was knighted in 1979. Among Finley’s best-known works are The Ancient Economy, Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology, and The World of Odysseus. BERNARD KNOX is director emeritus of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC. Among his many books are The Heroic Temper, The Oldest Dead White European Males, and Backing into the Future: The Classical Tradition and Its Renewal.