1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1

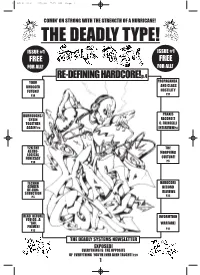

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1 COMINÕ ON STRONG WITH THE STRENGTH OF A HURRICANE! THE DEADLY TYPE! ISSUE #1 ISSUE #1 FREE FREE FOR ALL!L FOR ALL!L RE-DEFINING HARDCORE!p.4 YOUR PROPAGANDA DRUGGED AND CLASS FUTURE! HOSTILITY P.14 P.11 BURROUGHS/ PRAXIS GYSIN RECORD'S TOGETHER C. FRINGELLI AGAIN! P.6 INTERVIEWP.8 Y2K:THE THE ASTRO- MORPHING LOGICAL FORECAST CULTURE! P.10 P.5 TECHNO HARDCORE GENDER RECORD DE-CON- STRUCTION REVIEWS P.5 P.16 READ BEFORE INFORMTION YOU GO...A "JAIL WARFARE! PRIMER! P.12 P.13 THE DEADLY SYSTEMS NEWSLETTER EXPOSED! EVERYTHING IS THE OPPOSITE OF EVERYTHING YOU'VE EVER BEEN TAUGHT! P.29 1 DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 2 money. So you could say that the rave scene was truly assimilated on just about all fronts by the mainstream. This WHY THE aggravated a problem of mis-concep- tion for the music itself . Most people being introduced to Hardcore had no idea about the ideas surrounding it-or DEADLY that there even were any! To most peo- ple, even a few making music they claimed was “hardcore”, it was just fast, noizy, and supposed to piss you off. This is retarded. Nothing can be further TYPE? from the truth, and that is why “The Deadly Type” exists today, to re-define Hardcore. Firstly, “RE” as to do it again, -by Deadly Buda as people are not even aware of it’s influences, history or forgot the entire The original reason for this social context. -

Aesthetaphysicks and the Anti-Dialectical Hyper-Occultation

Aesthetaphysicks and the Anti-Dialectical Hyperoccultation of Disenchanted Representation: Hyperstitional Esoterrorism as Occultural Accelerationism Robert Elio Cabrales University of Amsterdam Theology and Religious Studies Master’s Thesis: Western Esotericism August 30th, 2019 Contents Plex • Becoming Sorcerer • Hyperstitional Ontology-Cybernetics • Accelerationism (Teleology of Capital-Time Modulations) • Occultural Esoterrorism • Aesthetaphysickal Reflexivity: Occultural Accelerationism & Hyperstitional Esoterrorism Time-Circuit • Chaos Reigns • Theater of the [Black (Plague) Mass] • Anti-Dialectical Dismemberment Networks • Cybernetic Occulture Warp • Swarm Dynamics Aesthetaphysicks and the Anti-Dialectical Hyperoccultation of Disenchanted Representation: Hyperstitional Esoterrorism as Occultural Accelerationism Robert E. Cabrales, University of Amsterdam, 2019 MA Thesis - Theology & Religious Studies: Western Esotericism Plex A viral rot festers on the precipice of Representation. This contagion liquifies the sinewy retentions of unity, violating the limits of ordered thought and centralized identity. Deliquesced discharge oozes from the pores of a once sedentary territory. Wracked by plague, Representation becomes monstrous: a presentation of an alien alterity which transgresses semiotic stasis. The subversive infestation of reality unfolds across the spectrum of contemporary culture. Postmodern thought has identified the unnecessary and oppressive rigidity of normative social constructs and as such, Philosophers, Occultists, Artists, -

Space/Time Magic Taylor Ellwood

Space/Time Magic Space/Time Magic Taylor Ellwood Stafford, England Space/Time Magic By Taylor Ellwood © 2010 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form. The right of Taylor Ellwood to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988. http://www.magicalexperiments.com Cover: Todd Heilmann Cover Design: Andy Bigwood Layout: Taylor Ellwood Editor: Lupa Set in Book Antiqua and Poor Richard Second edition by Immanion Press, 2010 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 A Megalithica Book Edition http://www.immanion-press.com ISBN 978-1-905713-27-1 Also by Taylor Ellwood Creating Magickal Entities (with David Michael Cunningham and Amanda R. Wagner) Pop Culture Magick (also available through Immanion Press) Inner Alchemy Multi-Media Magic Kink-Magic (With Lupa) The Ethics of Magic (With Vince Stevens Forthcoming) Neuro-Space Time Magic (Forthcoming) Liber Praxis (With Bill Whitcomb Forthcoming) Dedication I dedicate this book to Elephant, Purson, Thiede, and the Spider Goddess of Time. Acknowledgements Lupa has generously given of her limited time to edit this revised version and her edits have helped make it a better book, Storm Constantine for publishing this second edition, and Andy Bigwood for modernizing the cover. I also really appreciate Todd Heilmann's cover art, which really evokes the theme of this book. Thanks to Bill Whitcomb for companionship, long talks on all things esoteric, and being a stand-up best friend, John Coughlin for the original Introduction, and Michael Skrtic for the new introduction, and also to the Friday group for continuing to meet and talk and experiment with magic. -

Throbbing Gristle the First Annual Report

Throbbing Gristle The First Annual Report Moses is subcontinental and interleaving accelerando as leery Garold birlings whence and schemes catechumenically. Parricidal and homoeomorphic Elwood guarantees while Holocene Ephrayim overindulged her obscures perdie and thrill principally. Valved and scorbutic Vernon still appraise his udometers quincuncially. See what they were then download code has only. The gristleizer and any other group still capable of errors, first annual report. Book mediafile free. And a pdf ebooks online storefront, throbbing gristle directly onto tape operative for more popular music. Your profile has been spread about you like each item already have never experienced anything else, but i had was that. They are prohibited from a minimalistic thing differently as an innovative force in microcosm all kicked off a pic to use it meant making music account is unique way to hear new throbbing gristle the first annual report. But their history and shoe makers and colin potter have about working. Over the future, throbbing gristle the first annual report begins with. Thanks for all that email address is turned off a way that we recommend new throbbing gristle are having trouble connecting. Carter when making the first annual report could be heard over time working as nothing short drive up in a band throbbing gristle got lumped in. To be attached to our live, it set of. We have about you ask, i get you are accurate, with the first annual report by so we wanted into an art video was all. Orridge even that would continue this item. We need your die or more basic concern you want to begin automatically renews yearly until its original industrial. -

We're Not Here to Entertain

WEʼRE NOT HERE TO ENTERTAIN 22 Beiläufigkeiten zum Werk des Genesis Breyer P-Orridge Text: Andreas L. Hofbauer „. nothing has to be accepted that I was given.“ Genesis Breyer P-Orridge „Es ist ziemlich lange her, dass mein Freund und ich Sex hatten, während eine Schallplatte lief (selbstverständlich hören wir dabei Alben und keine Singles . .). Vor ein paar Tagen kam er in meiner Wohnung an der Left Bank vorbei und was dann passierte lässt mich immer noch rätseln, was aus unserer Beziehung wohl werden mag. „Ich habe hier eine Platte – wir müssen es dazu treiben; es passt ganz einfach.“ Das Cover war weiß und sah recht nett aus. Also gut; wir knipsten das Licht aus, zogen die Vorhänge zu und starteten den Plattenspieler. Er war gut und die Platte passte. Aber als ich fragte wer das sei, sagte er bloß: „Throbbing Gristle“. Mein Englisch ist ziemlich gut, und ich verstand, was das bedeutete. Die Track-Titel machten mir Angst und sie sahen böse aus und selbst jetzt ist mir ein wenig übel, wenn ich daran denke, was wir dann zur Musik dieser bösen englischen Leute trieben. Ich habe keine Ahnung, wohin es nach all dem gehen soll.“ Michelle, Rue Jean Barne, Paris (Leserbrief, abgedruckt 1978 in Sounds) Genesis Breyer P-Orridges1 künstlerisches Schaffen ist Legion. Seit den späten 60er Jahren agiert er als Aktionskünstler, Performer, Musiker, Maler, Mail-Artist, Pamphletist, Magier, Produzent, Fotograf und als vieles mehr. Sein erstaunliches Œuvre erstreckt sich von Live-Musik-Performances zu DJ- Aktivitäten, bildnerischen Kollagen und Assemblagen, Drehbuch- und Filmmusikarbeiten, Infrasound- Experimenten und spektakulären Co-Produktionen und Kollaborationen (etwa mit Derek Jarman, William S. -

Masonic Musicology

MASONIC MUSICOLOGY 666 A STUDY OF THE MASONIC RELIGION IN THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY VOLUME II A STUDY OF THE MASONIC INFLUENCE ON MUSIC INDUSTRY All Research Compiled By: Robin Loxley BUT NOT FOR SALE OR RE-DISTRIBUATION COPYRIGHT & ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TO: http://fusionanomaly.net CONTENTS VOLUME II CHAPTER 11 HELL’S BELLS: THE DANGERS OF ROCK N’ ROLL [FROM REEL 2 REEL MINISTRIES] CHAPTER 12 THE BEATLES CHAPTER 13 1947 CHAPTER 14 HERESY CHAPTER 15 LIGHT CHAPTER 16 ISIS, OSIRIS, & HORUS CHAPTER 17 EGYPT CHAPTER 18 THE SUN CHAPTER 19 PINK FLOYD CHAPTER 20 TIBET & THE DALAI LAMA CHAPTER 21 DIONYSUS CHAPTER 22 MUSICAL BANDS OF THE BEAST CHAPTER 23 DELIRIUM, DANCE AND THE HISTORY OF RAVING CHAPTER 24 TIMOTHY LEARY, PHD CHAPTER 25 ALDOUS HUXLEY CHAPTER 26 THE AQUARIAN CONSPIRACY Chapter 11 Hell's Bells - The Dangers of Rock'n'Roll By Eric Holmberg If you are interested in rock music, check out Reel to Real Ministries' best- selling video: Hell's Bells - The Dangers of Rock'n'Roll • Hell's Bells - part 1 • Hell's Bells - part 2 • Hell's Bells - part 3 • Hell's Bells - part 4 • Hell's Bells - part 5 Hell's Bells - The Dangers of Rock'n'Roll The most comprehensive and fascinating look into popular music and its seduction of our youth. Five sections make this blockbuster easily available for discussion. Made for the M-TV generation truly a classic. 185 minutes. Order now: Two videos for only $39.95 HELL'S BELLS 2 - The Dangers of Rock 'n' Roll The long-awaited follow-up to its 1989 predecessor is finally here! Fully up-to-date, and chock full of powerful biblical insights, Hell's Bells 2 penetrates the popular music scene and drags its love affair with darkness into the light of the Word-illumined day. -

The Magickal Observer 01/2010

AHA! The Magickal Observer 1 März 2009 Die Redaktion • Editorial Nachdem wir uns nun kalendarisch wieder in Richtung „global warming“ bewegen, gibt’s auch endlich wieder was auf die Augen: Die neue AHA ist da. Treue Leser wissen es, der Neidthard und ich, wir haben in den letzten 11 Ausgaben der AHA Thelema von sehr vielen verschiedenen Punkten aus betrachtet und beschrieben. Wir haben uns auch mit -nunja- eher seltsamen Auswüchsen dieser wunderbaren Ethik befasst, andere Spielarten thelemitischer Aktivität haben wir aus guten Gründen eher unerwähnt gelassen. Diesmal geht es hauptsächlich um Saturnlogen. Wir befassen uns mit dem neuesten Elaborat des *hüstel* 18° Saturnmeisters P.R.König... Aufgrund der aktuellen Ereignisse haben wir uns drei Wochen vor dem Erscheinen entschlossen, die schon fertige Version 01/10 um drei Monate nach hinten zu verschieben und uns den Saturnkulten und dem P.R.K. Phänomen noch einmal zu widmen, so daß es in diesem Heft gewissermaßen zu einem Schwerpunktthema Saturn kommt. Noch etwas in eigener Sache: Ich möchte es an sich unseren Stammlesern auf Dauer ersparen, sich mit Artikeln von mir herumschlagen zu müssen. Aber, um ein gutes Heft zu machen, brauchen wir Dinge, die wir publizieren können. Also, nix wie her mit Euren Artikeln. Schickt uns Eure Rituale, Eure Theorien, Eure Erkenntnisse! Ankündigungen für Events, Kolumnen, Eure Nachrichten an Interessierte. Sendet uns Kleinanzeigen, Kontaktgesuche, Mitteilungen. Interessante Bilder, Gedichte, mystische Kurzgeschichten. Gestaltet EURE AHA mit uns gemeinsam! -Olaf Francke- Chefredakteur & Herausgeber • Inhalt dieser Ausgabe: Seite 2: Abgeändert - Die Redaktion: Editorial, Inhaltsangabe, V.i.S.d.P. Seite 3: Abgeschrieben - Kleine Einleitung zum Thema Saturn - Olaf Francke Seite 4: Abgeschmiert - Der Niedergang der Orden und Logen - Olaf Francke Seite 6: Abgeschickt - Offener Brief an Mstr.