300296964-Oa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHELM in JERUSALEM by R. Seliger

CHELM IN JERUSALEM By R. Seliger It’s Sukkot, the holiday that requires observant Jews to feel the fragility of our existence by eating in the sukkah – the fragile temporary outdoor booth, exposed to the elements of early fall. I wrote this film review two years ago. If you have the opportunity, you should consider the delights of this unusual film. “Ushpizin” resembles an Isaac Bashevis Singer tale in its rendering of totally sincere (or naive) characters immersed in religious observances, a belief in miracles, and a personal relationship with the Almighty. The world of Jerusalem’s Hasidim is largely a ghetto in its isolation from the rest of modern Israel, but not quite. Two convicts, evading the law, show up at the doorstep of our hero, Moshe Bellanga, and his good wife Malli, on erev Sukkot. It turns out that one criminal was a friend from Moshe’s wayward days in Eilat before he became a Baal Tshuva [a newly observant Jew] as a Breslover Hasid. The Bellangas are overjoyed that the two can be their ushpizin – Aramaic for “holy guests” – for the holiday, as traditional lore enjoins. But there is nothing holy in how their low-life guests behave. That the virtually destitute Bellangas have a sukkah and the money to celebrate the festival at all are “miracles.” Actually, they are the result of perfectly explainable events, but the pious couple understands their dramatic change of fortune as divine intervention, as an answer to their devotion and a part of their ongoing dialogue with Hashem. Similarly, when bad fortune strikes, they are rendered bereft not only by the event itself, but also by the notion that they have done something displeasing in the eyes of God or, even more painfully, that their suffering has meaning they cannot fathom in the sacred scheme of things. -

Charles University, Faculty of Arts East and Central European Studies

Charles University, Faculty of Arts East and Central European Studies Summer 2016 Jewish Images in Central European Cinema CUFA F 380 Instructor: Kevin Johnson Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment Classes: Mon + Tue, 12.00 – 3.15, Wed 12.00 – 2.45, H201 (Hybernská 3, Prague 1) Course Description This course examines the portrayal of Jews and Jewish themes in the cinemas of Central Europe from the 1920s until the present. It considers not only depictions of Jews made by gentiles (sometimes with anti-Semitic undertones), but also looks at productions made by Jewish filmmakers aimed at a primarily Jewish audience. The selection of films is representative of the broader region where Czech, Slovak, Polish, Hungarian, Ruthenian, Ukranian, German, and Yiddish are (or were historically) spoken. Although attention will be given to the national-political context in which the films were made, most of the films by their very nature defy easy classification according to strict categories of statehood—this is particularly true for the pre-World War II Yiddish-language films. For this reason, the films will also be examined with an eye toward broader, transnational connections and global networks of people and ideas. Primary emphasis will be placed on two areas: (1) films that depict and document pre-Holocaust Jewish society in Central Europe, and (2) post-War films that seek to come terms with the Holocaust and the nearly absolute destruction of Jewish culture and tradition in the region. Weekly film screenings will be supplemented by theoretical readings related to the films or to concepts associated with them. -

Rutgers Jewish Film Festival Goes Virtual, November 8–22

The Allen and Joan Bildner Center BildnerCenter.rutgers.edu for the Study of Jewish Life [email protected] Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 12 College Avenue 848-932-2033 New Brunswick, NJ 08901-1282 Fax: 732-932-3052 October 20, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EDITOR’S NOTE: For press inquiries, please contact Darcy Maher at [email protected] or call 732-406-6584. For more information, please visit the website BildnerCenter.Rutgers.edu/film. RUTGERS JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL GOES VIRTUAL, NOVEMBER 8–22 NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. – Tickets are now on sale for the 21st annual Rutgers Jewish Film Festival, which will be presented entirely online from November 8 through 22. This year’s festival features a curated slate of award-winning dramatic and documentary films from Israel, the United States, and Germany that explore and illuminate Jewish history, culture, and identity. The virtual festival offers a user-friendly platform that will make it easy to view inspiring and entertaining films from the comfort and safety of one’s home. Many films will also include a Q&A component with filmmakers, scholars, and special guests on the Zoom platform. The festival is sponsored by Rutgers’ Allen and Joan Bildner Center for the Study of Jewish Life and is made possible by a generous grant from the Karma Foundation. The festival kicks-off on Sunday, November 8, with the opening film Aulcie, the inspiring story of basketball legend Aulcie Perry. A Newark native turned Israeli citizen, Perry put Israel on the map as a member of the Maccabi Tel Aviv team in the 1970s. -

March Chronicle.Indd

CONGREGATION NEVEH SHALOM March 2008/ADAR I/Adadr II 5768 CHRONICLE No. 6 This newsletter is supportedpp by y the Sala Kryszek y Memorial Publication Fund From the Pulpit Esther: The Paradigm of the Diaspora Jewish Existence If we accept the Exodus epic as our Jewish master story, then the drama contained in the scroll of Esther constitutes the paradigmatic story of Jewish existence in the Diaspora. A master story of an ethnic, religious or national entity is the central historical event or series of events that informs that society about its guiding values and principles. Clearly the Exodus from Egyptian bondage followed by the receipt of God’s revelation and wandering 40 years in the wilderness on their way to the Promised Land serves that primary purpose for Jews. God heard the cry of the oppressed and chose Moses as God’s instrument in challenging Pharaoh to liberate God’s own people. Once free, the Children of Israel came to Mt. Sinai where God gave them laws to live by in order to establish a moral society. Together they persevered until they were worthy of inheriting the land that God promised them as an everlasting inheritance. However instructive our master story is in defi ning our most highly treasured values, nearly 2000 years of our history were spent far from our ancestral home in lands of the Jewish Diaspora. We lived in foreign lands as a subject minority population. We did our best to simultaneously be loyal residents (because not until the French Revolution and the American experience were we considered full citizens) and maintain our distinct identity as Jews. -

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter Lebanon (2009) he timeless figure of the raw recruit overpowered by the shock of battle first attracted the full gaze of literary attention in Crane’s Red Badge of Courage (1894- T 95). Generations of Americans eventually came to recognize Private Henry Fleming as the key fictional image of a young American soldier: confused, unprepared, and pretty much alone. But despite Crane’s pervasive ironies and his successful refutation of genteel literary treatments of warfare, The Red Badge can nonetheless be read as endorsing battle as a ticket to manhood and self-confidence. Not so the First World War verse of Lieutenant Wilfred Owen. Owen’s antiheroic, almost revolutionary poems introduced an enduring new archetype: the young soldier as a guileless victim, meaninglessly sacrificed to the vanity of civilians and politicians. Written, though not published during the war, Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young,” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” especially, exemplify his judgment. Owen, a decorated officer who once described himself as a “pacifist with a very seared conscience,” portrays soldiers as young, helpless, innocent, and ill- starred. On the German side, the same theme pervades novelist Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928): Lewis Milestone’s film adaptation (1930) is often ranked among the best war movies of all time. Unlike Crane, neither Owen nor Remarque detected in warfare any redeeming value; and by the late twentieth century, general revulsion of the educated against war solicited a wide acceptance of this sympathetic image among Western War, Literature & the Arts: an international journal of the humanities / Volume 32 / 2020 civilians—incomplete and sentimental as it is. -

What to Watch When Jewish and in a Pandemic…

What to watch when Jewish and in a Pandemic….. Fill the Void – Apple Movie When the older sister of Shira, an 18-year-old Hasidic Israeli, dies suddenly in childbirth, Shira must decide if she can and should marry her widowed brother-in-law, which also generates tensions within her extended family. Tehran – Apple TV A Mossad agent embarks on her first mission as a computer hacker in her home town of Tehran. Marvelous Mrs. Mazel – Amazon Prime A housewife in 1958 decides to become a stand-up comic. Shtisel – Netflix The life of the Shtisel family, a haredi family in Jerusalem. Unorthodox – Netflix Story of a young ultra-Orthodox Jewish woman who flees her arranged marriage and religious community to start a new life abroad When Heroes Fly - Netflix Four friends, 11 years after a major falling out, reunite on a final mission: to find Yaeli, the former lover of one man and sister of another. Fauda – Netflix The human stories on both sides of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Defiance – YouTube Movies Jewish brothers in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe escape into the Belarussian forests, where they join Russian resistance fighters, and endeavor to build a village, in order to protect themselves and about one thousand Jewish non-combatants. Munich – YouTube Movies Based on the true story of the Black September aftermath, about the five men chosen to eliminate the ones responsible for that fateful day (Directed by Steven Spielberg) Mrs America – YouTube Movies, Hulu Mrs. America serves "as an origin story of today’s culture wars, Mrs. America is loosely based on and dramatizes the story of the movement to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment, and the unexpected backlash led by conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, played by Blanchett. -

Hereinspaziert! Ein Heft Übers Anfangen

Reihe 5 Hereinspaziert! Ein Heft übers Anfangen Das Magazin der Staatstheater Stuttgart Nr. 13 Staatsoper Stuttgart, Schauspiel Stuttgart, Stuttgarter Ballett Sept – Nov 2018 Sehr geehrte Leserinnen und Leser, Mitwirkende dieser Ausgabe jedem Ende wohnt ein Anfang inne! Weil wir im vorigen Heft Abschied von gleich drei Intendanten feierten, begrüßen wir nun die neuen, die mitsamt ihren Teams am Stuttgarter Ballett, an der Staatsoper Stuttgart und am Schauspiel Stuttgart starten. Ihre Arbeit haben Tamas Detrich, Viktor Schoner und Burkhard Kosminski aber schon vor Monaten, teilweise vor Jahren aufgenommen. Die Bühnenkünste sind eine Kombina tion ROMAN NOVITZKY ist ein Mehrfachbegabter: aus Marathon und Kurzstrecke. Pläne werden Jahre im Voraus Er ist Erster Solist, Cho gemacht, orientiert an der Verfügbarkeit der Künstler. Für Proben reograph – und Fotograf. Für Reihe 5 hat er zwei bleiben manchmal nur Wochen. Die Kunst besteht darin, Kolle ginnen inszeniert. Seite 30 diese unterschiedlichen Laufwege zu orchestrieren, damit alle gleichzeitig ins Ziel, also auf die Bühne, kommen. Statt jedoch nun Gebrauchsanleitungen für Dinge zu liefern, die noch weit vor uns liegen, schauen wir auf die nächsten drei Monate und entdecken dort, wen wundert es: lauter Themen für Anfänge. Im Interview erklärt Cornelius Meister, der neue General musikdirektor der Staatsoper Stuttgart, warum er mit John Cages HARALD WELZER 4' 33" einsteigt, jenem Werk, das aus nichts als Stille besteht. Der Sozialpsychologe weiß, wie Krieg entsteht und das Lernen Sie Tamas Detrich kennen, den neuen Intendanten des Morden gedeiht. Deswe gen Stuttgarter Balletts, einen wahren Meister des Beginnens. gehört die Gewalt auf die Bühne. Mit Geschichten, Der Dynamik eine perfekte Form zu geben. -

[email protected] (You Know, the Ones That Took the 126 That It Will Never Work

ב''ה 230 hale lane , edgware middx, ha8 9pz Volume 29 • Tishrei 5775 HOLIDAYGUIDEHOLIDAYGUIDE HOWHOW WILLWILL HEHE EARNEARN AA LIVINLIVINGG FFIDDLERIDDLER’S’S QQUEUESTSTIONION Table of Contents 8 24 10 7 featured 7 That’s alright, you can do it . 8 How will he earn a living? 10 Holiday Guide 14 Tishrei Calendar 20 Fiddler’s question 24 Yusta regular From the Editor 4 Message from the Rebbe 5 Lubavitch of Edgware News 16 Candle Lighting Times and Blessings 19 Lubavitch of Radlett News 22 Letters 26 20 3 Editorial Torah PUBLISHER Chadron Ltd on behalf of Lubavitch of Edgware. A division of Chabad Lubavitch UK Registered Charity No. 227638 EDITORIAL Editor: Mrs. Feige Sudak JUST A PINHOLE rom my earliest days i had a knows that to us the whole concept of ADVERTISING fascination for science and Teshuva – return is daunting and leaves To advertise please call technology. i was only eight years us very scared. particularly, as we come 020 8905 4141 F old when i managed to collect enough close to rosh hashanah and then even to SUBSCRIPTIONS ‘cigarette vouchers’ from my father’s Yom Kippur, the notion that we can repair Phone: smoking habit (in those days smoking our past and come to be close with g-d 020 8905 4141 was an acceptable form of behaviour) to is so distant from us that we just do not Email: exchange for a Kodak instamatic Camera believe it. so, we fight it off with excuses [email protected] (you know, the ones that took the 126 that it will never work. -

Judy Moseley Executive Director PIKUACH NEFESH

TEMPLE BETH-EL Congregation Sons of Israel and David Chartered 1854 Summer 2020 Sivan/Tammuz/Av 5780 THE SHOFAR Judy Moseley Executive Director PIKUACH NEFESH PIKUACH NEFESH, the principle of “saving a life,” is Temple Beth-El staff will begin to work in the building on a paramount in our tradition. It overrides all other rules, including rotating basis, and will work from our homes when necessary. We the observance of Shabbat. We have been consulting with some of will continue to be available to you through email and phone. the leading health institutions in our city, and they have been clear We will communicate any changes as appropriate. that one of the most important goals is to help “flatten the curve,” to We will be seek additional ways to build community in creative slow down the spread of the virus through social distancing, ways, taking advantage of technologies available to us, in which we thereby lessening the potential for overburdening our healthcare have invested. Please check your email for programming and systems. Given our tradition’s mandate to save lives above all other updates. mitzvot, the leadership team has made the very difficult decision to When I was younger and sneezed, my grandmother used to say, continue “virtual” services at this time. This is one of those moments “Gesundheit! To your good health.” I never really appreciated the when a community is tested, but can still provide sanctuary — even blessing embedded in that sentiment, but I offer it to all of you as we when we cannot physically be in our spiritual home. -

Kärlek Och Livsval På Jiddisch

TV-SERIER UNORTHODOX OCH SHTISEL PRODUKTION NETFLIX Kärlek och livsval på jiddisch Pltsligt märker jag att studenter Akiva däremot, anlitar en äktenskapsmäklare i klassrumsdiskussioner titt som som freslår olika lämpliga fickor. Problemet är att han egentligen har frälskat sig i den tätt refererar till livet som haredi något äldre Elisheva som redan två gånger (ultraortodox jude). Självklart har blivit änka. Det innebär att hon enligt halachan betraktas som en ishah katlanit (”ddlig talar de om yeshiva, cheder, an- kvinna”). Män avråds från att gifta sig med ständig klädsel och arrangerade sådana kvinnor fr att de inte ska riskera att gå äktenskap. Frklaringen var enkel. samma de till mtes som hennes frsta två män. Både Esty och Akiva frsker också tänja på Serien Unorthodox hade brjat ramarna fr vilket liv som anses lämpligt fr visas på Netfix. dem. Esty smyger i hemlighet iväg till bibliote- ket och lånar bcker som hon gmmer under Båda serierna De båda TV-serierna Unorthodox och Shtisel madrassen och läser i smyg. Akiva älskar att har fr många inneburit helt nya inblickar i hur teckna och får så småningom jobb hos en känd kan utan denna typ av judiskt liv kan te sig. konstnär som inte hinner producera tavlor så tvekan ge Unorthodox är en tysk/amerikansk produktion snabbt som de säljs. Istället får Akiva och andra som handlar om den unga fickan Esty som växer okända konstnärer måla tavlorna som han sedan inblickar i en upp inom satmarrrelsen i New York. Serien är bara signerar. livsstil som de delvis baserad på Deborah Feldmans självbiogra- Men det fnns också stora skillnader. -

Record 63 Independent Pilots Selected for the 12Th

Press Note – please find assets at the below links: Photos – https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B-lTENXjpYxaWmEtRTIzSVozcFU Trailers – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIUPrhfxAzsCs0VylfwQ-PEtiGDoQIKOT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RECORD 63 INDEPENDENT PILOTS SELECTED FOR THE 12TH ANNUAL NEW YORK TELEVISION FESTIVAL *** As Official Artists, Creators will Enjoy Opportunities with Network, Digital, Agency and Studio execs at October TV Fest Independent Pilot Competition Official Selections to be Screened for the Public from October 24-29, Including 42 World Festival Premieres [NEW YORK, NY, August 15, 2016] – The NYTVF (www.nytvf.com) today announced the Official Selections for its flagship Independent Pilot Competition (IPC). A record-high 63 original television and digital pilots and series will be presented for industry executives and TV fans at the 12th Annual New York Television Festival, including 42 world festival premieres, October 24-29, 2016 at The Helen Mills Theater and Event Space, with additional Festival events at the Tribeca Three Sixty° and SVA Theatre. The slate of in-competition projects was selected from the NYTVF's largest pool of pilot submissions ever: up more than 42 percent from the previous high. Festival organizers also noted that the selections are representative of creative voices across diverse demographics, with 59 percent having a woman in a core creative role (creator, writer, director and/or executive producer) and 43 percent including one or more persons of color above the line (core creative team and/or lead actor). “We were blown away by the talent and creativity of this year's submissions – across the board it was a record-setting year and we had an extremely difficult task in identifying the competition slate. -

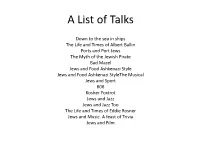

A List of Talks

A List of Talks Down to the sea in ships The Life and Times of Albert Ballin Ports and Port Jews The Myth of the Jewish Pirate Bad Mazel Jews and Food Ashkenazi Style Jews and Food Ashkenazi StyleThe Musical Jews and Sport 606 Kosher Foxtrot Jews and Jazz Jews and Jazz Too The Life and Times of Eddie Rosner Jews and Music. A feast of Trivia Jews and Film PORTS AND PORT JEWS The Port City was the gateway to settlement for Jews on their many migrations. Sometimes they stayed and settled, often they moved on to the hinterland. Before the advent of the aeroplane Port Cities were vital for the continuance of Jewish life. They enabled multi-continental networks to be set up, as well as providing a place of refuge and an escape hatch. Many of the places have now faded in our collective memory, but remain a vibrant part of the history of the last 2000 years. Tony will show you how those Port Jews adapted, survived, and even flourished. Including • The merchants of antiquity • The Atlantic triangle • Port Jews – Hull and Charleston • Odessa and Trieste – the Free Ports • City of Mud and Jews • The fishermen of Salonika - and Haifa • The last Port Jews The Myth of the Jewish Pirate Over the past few years an industry has grown up around the myth of the Jewish Pirate. There has been an exhibition in Marseille; a book called Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean; there are guided tours in Jamaica, and Jewish speakers regularly give talks on the subject.