Maps and Utopian Constructions of Space in L. Frank Baum’S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wonderful Wizards Behind the Oz Wizard

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 1997 The Wonderful Wizards Behind the Oz Wizard Susan Wolstenholme Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wolstenholme, Susan. "The Wonderful Wizards behind the Oz Wizard," The Courier 1997: 89-104. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXII· 1997 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXII 1997 Ivan Mestrovic in Syracuse, 1947-1955 By David Tatham, Professor ofFine Arts 5 Syracuse University In 1947 Chancellor William P. Tolley brought the great Croatian sculptor to Syracuse University as artist-in-residence and professor ofsculpture. Tatham discusses the his torical antecedents and the significance, for Mdtrovic and the University, ofthat eight-and-a-half-year association. Declaration ofIndependence: Mary Colum as Autobiographer By Sanford Sternlicht, Professor ofEnglish 25 Syracuse University Sternlicht describes the struggles ofMary Colum, as a woman and a writer, to achieve equality in the male-dominated literary worlds ofIreland and America. A CharlesJackson Diptych ByJohn W Crowley, Professor ofEnglish 35 Syracuse University In writings about homosexuality and alcoholism, CharlesJackson, author ofThe Lost TtVeekend, seems to have drawn on an experience he had as a freshman at Syracuse University. Mter discussingJackson's troubled life, Crowley introduces Marty Mann, founder ofthe National Council on Alcoholism. Among her papers Crowley found a CharlesJackson teleplay, about an alcoholic woman, that is here published for the first time. -

The Marvellous Land of Oz ______

The Chronicles of Oz: The Marvellous Land Of Oz __________________________ A six-part audio drama by Aron Toman A Crossover Adventures Production chroniclesofoz.com 44. EPISODE TWO 15 PREVIOUSLY Recap of the previous episode. 16 EXT. CLEARING The Sawhorse runs rampant, while Tip and Jack Pumpkinhead attempt to catch it and calm it down. JACK PUMPKINHEAD Whoah! Whoah! TIP (V.O.) Taming the Sawhorse now it was alive was proving ... tricky. When Jack came to life, he was full of questions and kinda stupid, but he was fairly calm, all things considered. The Sawhorse was frightened. And a little bit insane. JACK PUMPKINHEAD Calm down horsey! TIP Whoah, horse. Easy there boy -- look out Jack, it's coming through! JACK PUMPKINHEAD Whoooah! He leaps out of the way as the horse bounds past him. TIP Come on, there's nothing to be scared of. JACK PUMPKINHEAD I'm scared! TIP Nothing for the Sawhorse to be scared of. (to Sawhorse) We're your friends we're not going to hurt -- ahhh! He jumps aside as it rushes through. 45. JACK PUMPKINHEAD At least it's knocking you over as well as me, Dad. TIP I don't understand, why won't it listen to us? JACK PUMPKINHEAD Maybe it can't listen to us? TIP Oh? Oh, of course, that's it! Jack, find me some leaves or something. (he starts rummaging in the undergrowth) Big ones, about the size of my hand. We need two. JACK PUMPKINHEAD Why? TIP (finding leaves) Here we are, perfect. Ears, Jack! The Sawhorse doesn't have ears! JACK PUMPKINHEAD That's why he isn't listening! TIP We just need to fasten these on to his head and sprinkle a little more powder on. -

Gen. Jinjur's Army of Revolt Tip Was So Anxious to Rejoin His Man

Gen. Jinjur's Army of Revolt Tip was so anxious to rejoin his man Jack and the Saw-Horse that he walked a full half the distance to the Emerald City without stopping to rest. Then he discovered that he was hungry and the crackers and cheese he had provided for the Journey had all been eaten. While wondering what he should do in this emergency he came upon a girl sitting by the roadside. She wore a costume that struck the boy as being remarkably brilliant: her silken waist being of emerald green and her skirt of four distinct colors--blue in front, yellow at the left side, red at the back and purple at the right side. Fastening the waist in front were four buttons--the top one blue, the next yellow, a third red and the last purple. The splendor of this dress was almost barbaric; so Tip was fully justified in staring at the gown for some moments before his eyes were attracted by the pretty face above it. Yes, the face was pretty enough, he decided; but it wore an expression of discontent coupled to a shade of defiance or audacity. While the boy stared the girl looked upon him calmly. A lunch basket stood beside her, and she held a dainty sandwich in one hand and a hard-boiled egg in the other, eating with an evident appetite that aroused Tip's sympathy. 62 He was just about to ask a share of the luncheon when the girl stood up and brushed the crumbs from her lap. -

OZ IS TWISTED a Play

OZ IS TWISTED a play Book By Joe Ferriero Based on the Story By L. Frank Baum Acting Script Final Copy May, 2011 Protected by Copyright i Cast of Characters Real World Characters: Dorothy Gale ....................... 16 years old, New York High Schooler James Gale ................................................ Dorothy’s Dad Aunt Em .................................................. Dorothy’s Aunt Uncle Henry ............................................. Dorothy’s Uncle Sheriff ............................................ of small Kansas town Toto ..................................... a stuffed toy, not a real dog! Willy, Edna, Margret ......................................... farm hands Oz Characters: Boq ............................................................. Munchkin Loq .................................................... Another Munchkin Toq ..................................................... Another Munchkin Glinda ....................................... the Good Witch of the South Locasta ...................................... the Good Witch of the North Bastinda ........................................ Wicked Witch of the West Scarecrow ..................... found in the outskirts of Munchkin Country Tinman .................... Was called Nick Chopper, now made fully of tin Cowardly Lion ................................ a lion in search of courage The Crow Bars ................................. a singing group of 3 Crows Pine and Oak .............................................. Fighting Trees Wizard of Oz ..................................... -

The Patchwork Girl of Oz

The Patchwork Girl of Oz By L. Frank Baum THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ Chapter One Ojo and Unc Nunkie "Where's the butter, Unc Nunkie?" asked Ojo. Unc looked out of the window and stroked his long beard. Then he turned to the Munchkin boy and shook his head. "Isn't," said he. "Isn't any butter? That's too bad, Unc. Where's the jam then?" inquired Ojo, standing on a stool so he could look through all the shelves of the cupboard. But Unc Nunkie shook his head again. "Gone," he said. "No jam, either? And no cake—no jelly—no apples—nothing but bread?" "All," said Unc, again stroking his beard as he gazed from the window. The little boy brought the stool and sat beside his uncle, munching the dry bread slowly and seeming in deep thought. "Nothing grows in our yard but the bread tree," he mused, "and there are only two more loaves on that tree; and they're not ripe yet. Tell me, Unc; why are we so poor?" The old Munchkin turned and looked at Ojo. He had kindly eyes, but he hadn't smiled or laughed in so long that the boy had forgotten that Unc Nunkie could look any other way than solemn. And Unc never spoke any more words than he was obliged to, so his little nephew, who lived alone with him, had learned to understand a great deal from one word. "Why are we so poor, Unc?" repeated the boy. "Not," said the old Munchkin. "I think we are," declared Ojo. -

THE WACKY WIZARD of OZ by Patrick Dorn

THE WACKY WIZARD OF OZ By Patrick Dorn Copyright © 2015 by Patrick Dorn, All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-60003-837-2 CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this Work is subject to a royalty. This Work is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention. RIGHTS RESERVED: All rights to this Work are strictly reserved, including professional and amateur stage performance rights. Also reserved are: motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information and storage retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into non-English languages. PERFORMANCE RIGHTS AND ROYALTY PAYMENTS: All amateur and stock performance rights to this Work are controlled exclusively by Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. No amateur or stock production groups or individuals may perform this play without securing license and royalty arrangements in advance from Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Questions concerning other rights should be addressed to Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice. Professional and stock fees will be set upon application in accordance with your producing circumstances. Any licensing requests and inquiries relating to amateur and stock (professional) performance rights should be addressed to Brooklyn Publishers, LLC. Royalty of the required amount must be paid, whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. -

To the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005)

Index to the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005) Adams, Ryan Author "Return to The Marvelous Land of Oz Producer In Search of Dorothy (review): One Hundred Years Later": "Answering Bell" (Music Video): 2005:49:1:32-33 2004:48:3:26-36 2002:46:1:3 Apocrypha Baum, Dr. Henry "Harry" Clay (brother Adventures in Oz (2006) (see Oz apocrypha): 2003:47:1:8-21 of LFB) Collection of Shanower's five graphic Apollo Victoria Theater Photograph: 2002:46:1:6 Oz novels.: 2005:49:2:5 Production of Wicked (September Baum, Lyman Frank Albanian Editions of Oz Books (see 2006): 2005:49:3:4 Astrological chart: 2002:46:2:15 Foreign Editions of Oz Books) "Are You a Good Ruler or a Bad Author Albright, Jane Ruler?": 2004:48:1:24-28 Aunt Jane's Nieces (IWOC Edition "Three Faces of Oz: Interviews" Arlen, Harold 2003) (review): 2003:47:3:27-30 (Robert Sabuda, "Prince of Pop- National Public Radio centennial Carodej Ze Zeme Oz (The ups"): 2002:46:1:18-24 program. Wonderful Wizard of Oz - Czech) Tribute to Fred M. Meyer: "Come Rain or Come Shine" (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 2004:48:3:16 Musical Celebration of Harold Carodejna Zeme Oz (The All Things Oz: 2002:46:2:4 Arlen: 2005:49:1:5 Marvelous Land of Oz - Czech) All Things Oz: The Wonder, Wit, and Arne Nixon Center for Study of (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 Wisdom of The Wizard of Oz Children's Literature (Fresno, CA): Charobnak Iz Oza (The Wizard of (review): 2004:48:1:29-30 2002:46:3:3 Oz - Serbian) (review): Allen, Zachary Ashanti 2005:49:2:33 Convention Report: Chesterton Actress The Complete Life and -

Kid-Friendly*” No Matter What Your Reading Level!

Advanced Readers’ List “Kid-friendly*” no matter what your reading level! *These are suggestions for people who love challenging words and a good story, and want to avoid age-inappropriate situations. Remember though, these books reflect the times when they were written, and sometimes include out-dated attitudes, expressions and even stereotypes. If you wonder, its ok to ask. If you’re bothered, its important to say so. The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein A young boy grows to manhood and old age experiencing the love and generosity of a tree which gives to him without thought of return. Also by Shel Silverstein: Where the Sidewalk Ends: The Poems and Drawings of Shel Silverstein A boy who turns into a TV set and a girl who eats a whale are only two of the characters in a collection of humorous poetry illustrated with the author's own drawings. A Light in the Attic A collection of humorous poems and drawings. Falling Up Another collection of humorous poems and drawings. A Giraffe and a Half A cumulative tale done in rhyme featuring a giraffe unto whom many kinds of funny things happen until he gradually loses them. The Missing Piece A circle has difficulty finding its missing piece but has a good time looking for it. Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook Runny Babbit speaks a topsy-turvy language along with his friends, Toe Jurtle, Skertie Gunk, Rirty Dat, Dungry Hog, and Snerry Jake. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame Emerging from his home at Mole End one spring, Mole's whole world changes when he hooks up with the good-natured, boat-loving Water Rat, the boastful Toad of Toad Hall, the society-hating Badger who lives in the frightening Wild Wood, and countless other mostly well-meaning creatures. -

A Irrealidade No Cinema Contemporâneo: Matrix & Cidade

A IRREALIDADE NO O cinema contemporâneo está repleto de lmes que nos desaam “[...] Em Matrix, o leitor-modelo é encorajado, CINEMA CONTEMPORÂNEO constantemente a separar ilusão e através de referências intertextuais ao cinema de Matrix & Cidade dos Sonhos verdade, sonho e vigília, real e gênero, a acreditar estar assistindo a um lme de virtual, sanidade e loucura, vida e espionagem até o momento em que Neo, o morte... protagonista, atravessa o espelho para fora do Adriano Oliveira Matrix (The Matrix, 1999) e ventre cibernético. Em Cidade dos Sonhos, o Cidade dos Sonhos (Mulholland Dr., leitor-modelo é induzido a prestar atenção na 2001) são casos exemplares: suposta trama policial linear e a ignorar os telefones, plugs cibernéticos, inúmeros, mas fragmentários, indícios de que tudo chaves e caixas azuis demarcam não passa de um sonho. Matrix deseja um pontos de passagem entre leitor-modelo que experimente a revelação de universos paralelos em tramas que Adriano Oliveira nasceu em forma tão vertiginosa quanto Neo. Cidade dos levam protagonistas e plateia a Salvador, Bahia, em 1970. Sonhos deseja um leitor-modelo que saia da compartilhar a angústia da Psicólogo, estudou psicanálise exibição incomodado por não conseguir assimilar impossibilidade de discernimento lacaniana por vários anos. a experiência e volte para empreender uma entre realidade e irrealidade. Atualmente exerce sua paixão segunda leitura. Matrix convida o leitor para uma Enredos assim estruturados pela sétima arte como professor do volta linear na montanha-russa. Cidade dos remontam a obras clássicas, mas o curso de Cinema e Audiovisual da Sonhos arrasta o leitor a um bosque de caminhos fascínio que exercem atualmente Universidade Federal do Recôncavo que se bifurcam e esconde-lhe o o de Ariadne.” parece indicar um diálogo da Bahia, na cidade histórica de profundo com a nossa época. -

Munchkin Categories

Sleepyheads:7-pink, tan or white ballet Soldiers:10 white 1. Lily Gauvin 1. Mary Ellis 2. Emily Kerr 2. Haley Follbaum 3. Sydney Robinson 3. Nicole Kasprzynski 4. Dylan Patel 4. Katie Kobiljak 5. Katie Slowik 5. Serena Norscia 6. Haley Anne Hobbs 6. Elizabeth Rutkowski 7. Bella Chelemen 7. Claire Schultze 8. Gabrielle Weil Lollipop guild:3 black jazz or 9. Kendall Manthai -speaks ballet #1Munch. 1. Jacob Gonzalez 10. Karlina Kontos 2. Jake Gillette 3. Salvador Delatorre Munchkinland Citizens:20 1. Jacob Barwikowski- TAN jazz Fiddlers:2 tan or white ballet or ballet 1. Paige Haris 2. Katrina Catabian-* 2. Aubrey Velmure 3. Christina Cobetto-* 4. Madeline Douglas-* Trumpeter:7 tan or white ballet 5. Tara Drinane-* 1. Katrina Catabian 6. Lauren Drinane* 2. Sarah Huffmaster 7. Josh Gonzales- TAN jazz or 3. Marissa McMullen ballet 4. Callie Pilkington 8. Christine Grady* 5. Anna Shumate 9. Claire Hedke* 6. Olivia Spicer 10. Samantha Hurtado* 7. Alyssa Vermette 11. Grace Krawczyk* 12. Asia Malwitz* Lullaby League:3 white ballet 13. Myah McCormick* 1. Dempsi Rosales 14. Lexi Nadolsky* 2. Kayla Cobetto 15. Justine Nagy* 3. Isabel Haack 16. Katelynne Powers* 17. Grace Ray* Birdcage Kids:3 tan or white ballet 18. Kayla Smith* or jazz 19. Marissa Smith* 1. Leo Richards 20. Garett Stone- BLACK jazz or 2. Tommy Shumate ballet 3. Kaden Manthei *may be tan, pink, or white ballet whatever looks best with costume or that you have – we have several loaners to try at office MUNCHKIN CATEGORIES Jitterbug Dancers20 Named MunchkinCitizens9 ( 18 PLUS MR/MS) As listed Mary Janes for girls Mayor‐ Dominic Garcia ‐black Black Jazz for boys Coroner‐ Xander Fleming‐ black *Ms. -

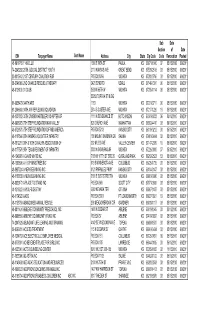

Sub Date Section of Date EIN Taxpayer Name Sort Name

Sub Date Section of Date EIN Taxpayer Name Sort Name Address City State Zip Code Code Revocation Posted 48-0916715 1149 CLUB 1006 E WEA ST PAOLA KS 66071-1840 07 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 74-2843202 20TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT YOUTH 2110 KANSAS AVE GREAT BEND KS 67530-2516 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 20-0815642 21ST CENTURY COALITION FOR PO BOX 8766 WICHITA KS 67208-0766 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 38-3746086 2ND CHANCE RESCUE & THERAPY 2420 32ND RD UDALL KS 67146-7301 00 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-6126100 31 CLUB 3539 N 55TH W WICHITA KS 67205-1114 09 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 53283 TOPEKA ST BLDG 01-0658479 344TH ARS 1183 WICHITA KS 67221-3711 00 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 91-2046668 34TH AIR REFUELING SQUADRON 2814 S CUSTER AVE WICHITA KS 67217-1226 19 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1037882 35TH DIVISION ARTILLERY CHAPTER OF 1111 N SEVERANCE ST HUTCHINSON KS 67501-5833 06 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-0908975 7TH STEP FOUNDATION KAW VALLEY 820 CHURCH AVE MANHATTAN KS 66502-4410 03 09/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-0729370 7TH STEP FOUNDATION OF MID AMERICA PO BOX 5212 KANSAS CITY KS 66119-0212 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1107546 8TH KANSAS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY 100 MOUNT BARBARA DR SALINA KS 67401-3444 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1012210 9TH & 10TH CAVALRY ASSOCIATION OF 202 MILES AVE VALLEY CENTER KS 67147-2039 19 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1177576 9TH TEXAS REGIMENT OF INFANTRY 3033 N GOVERNOUR WICHITA KS 67226-0000 07 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1249979 A DAVIS WHITE INC 7180 W 107TH ST STE 26 OVERLAND PARK KS 66212-2523 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1000596 A H G P MINISTRIES INC 619 S MINNESOTA AVE COLUMBUS KS -

Follow the Yellow Brick Road

CASA’s 7th Annual Red Wagon Event Follow the Yellow Brick Road There’s No Place Like Home Friday, April 7th, 2017 6:00 p.m. Fairgrounds Industrial Building There are over 300 kids each year that are appointed to CASA of There’s No Place Like Natrona County, and placed in the foster care system. Like Dorothy, when she first lands in Munchkin Land, these youth are oftentimes forced to navigate the complexities of life on their own. It only takes Home one caring person to change the course of their life for the better. Dorothy’s lucky—she found three! Together they were able to achieve their goal of finding the Emerald City and meeting the Wizard of Oz. CASA of Natrona County matches foster youth with specially trained, court appointed volunteers who provide on-going support, guid- ance and hope. CASA advocates change lives and help ensure our community’s most at-risk youth have a safe place to call home. You will hear stories, much like the Tin Woodman, Cowardly Lion and Scarecrow—from the Foster/ Adoptive Family, CASA Advocate, Guardian ad Litem and most importantly, the child. They all play an im- portant part in the success and outcome of finding a safe place to call HOME. Hear one adoption story through the perspective of everyone on the case. As there were many setbacks and delays in Dorothy’s trip to get home, there are similar delays, struggles and setbacks that can happen before a child in the foster care system is finally able to get back home.