Rural Imaginary in Italian Colonial Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

The 2011 Libyan Revolution and Gene Sharp's Strategy of Nonviolent Action

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2012 The 2011 Libyan revolution and Gene Sharp's strategy of nonviolent action : what factors precluded nonviolent action in the 2011 Libyan uprising, and how do these reflect on Gene Sharp's theory? Siobhan Lynch Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Political History Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Lynch, S. (2012). The 2011 Libyan revolution and Gene Sharp's strategy of nonviolent action : what factors precluded nonviolent action in the 2011 Libyan uprising, and how do these reflect on Gene Sharp's theory?. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/74 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/74 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Use of Thesis This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. -

Messinesi Insigni Del Sec. Xix Sepolti Al Gran Camposanto

GIORGIO ATTARD MESSINESI INSIGNI DEL SEC. XIX SEPOLTI AL GRAN CAMPOSANTO (Epigrafi - Schizzi Biografici) ,. • < in copertina: Messina, Gran Camposanto: Cappella Peirce (ing. V. Vinci) SOCIETÀ MESSINESE DI STORIA PATRIA REPRINT OPUSCOLI l 1. G. ATTARD Messinesi insigni del sec. XIX sepolti al Gran Camposanto (Epigrafi, Schizzi Biografici), 2" ed., a cura di G. Molonia, Messina 19912 (1926) SOCIETÀ MESSINESE DI STORIA PATRIA GIORGIO ATTARD MESSINESI INSIGNI DEL SEC. XIX SEPOLTI AL GRAN CAMPOSANTO (Epigrafi - Schizzi Biografici) Seconda Edizione a cura di GIOVANNI NfOLONIA MESSINA 1991 Vincenzo Giorgio Attard (Messina 1878 - 1956) INTRODUZIONE Nella raccolta di immagini di Messina preterremoto pervenuta attraverso Gaetano La Corte Cailler si trova una vecchia fotografia di Ledru Mauro raffigurante il "Gran Camposanto di Messina: il Famedio". In primo piano, seduto, è un anziano signore con una grande barba bianca con accanto, sdraiata a suo agio sul prato, una esile figura di ragazzo. In basso è la scritta di pugno del La Corte: "Il custode Attard e suo nipote". Giorgio Attard senior fu il primo custode-dirigente del Gran Cam posanto di Messina, di quell'opera cioè - vanto della municipalità peloritana - che, iniziata nel 1865 su progetto dell'architetto Leone Savoja, era statainauguratail6 aprile 1872 conIa solenne tumulazione delle ceneri di Giuseppe La Farina. Di antica e nobile famiglia maltese, Attard si era trasferito a Messina agli inizi dell 'Ottocento. Qui era nato il lO febbraio 1878 il nipote Vincenzo Giorgio Attard da Eugenio, ingegnere delle Ferrovie dello Stato, e da Natalizia Grasso. Rimasto orfano di padre in tenera età, Giorgio junior crebbe e fu educato dal nonno, che gli trasmise l'amore per il Camposanto sentito come "il sacro luogo dove si conservano le memorie della Patria, silenziose e nobili nel verde della ridente collina, sede degna per un sereno riposo". -

Big Sandbox,” However It May Be Interpreted, Brought with It Extraordinary Enchantment

eScholarship California Italian Studies Title The Embarrassment of Libya. History, Memory, and Politics in Contemporary Italy Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9z63v86n Journal California Italian Studies, 1(1) Author Labanca, Nicola Publication Date 2010 DOI 10.5070/C311008847 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Embarrassment of Libya: History, Memory, and Politics in Contemporary Italy Nicola Labanca The past weighs on the present. This same past can, however, also constitute an opportunity for the future. If adequately acknowledged, the past can inspire positive action. This seems to be the maxim that we can draw from the history of Italy in the Mediterranean and, in particular, the history of Italy's relationship with Libya. Even the most recent “friendship and cooperation agreement” between Italy and Libya, signed August 30, 2008 by Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and Libyan leader Colonel Moammar Gadhafi, affirms this. Italy’s colonial past in Libya has been a source of political tensions between the two nations for the past forty years. Now, the question emerges: will the acknowledgement of this past finally help to reconcile the two countries? The history of Italy’s presence in Libya (1912-1942) is rather different from the more general history of the European colonial expansion. The Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (referred to by the single name “Libya” in the literary and rhetorical culture of liberal Italy) were among the few African territories that remained outside of the European dominion, together with Ethiopia (which defeated Italy at Adwa in 1896) and rubber-rich Liberia. -

A Struggle for Every Single Boat

A Struggle for Every Single Boat Alarm Phone: Central Mediterranean Analysis, July - December 2020 ‘Mother’ I do not like death as you think, I just have no desire for life… I am tired of the situation I am in now.. If I did not move then I will die a slow death worse than the deaths in the Mediterranean. ‘Mother’ The water is so salty that I am tasting it, mom, I am about to drown. My mother, the water is very hot and she started to eat my skin… Please mom, I did not choose this path myself… the circumstances forced me to go. This adventure, which will strip my soul, after a while… I did not find myself nor the one who called it a home that dwells in me. ‘Mother’ There are bodies around me, and others hasten to die like me, although we know whatever we do we will die.. my mother, there are rescue ships! They laugh and enjoy our death and only photograph us when we are drowning and save a fraction of us… Mom, I am among those who will let him savor the torment and then die. Whatever bushes and valleys of my country, my neighbours’ daughters and my cousins, my friends with whom I play football and sing with them in the corners of homes, I am about to leave everything related to you. Send peace to my sweetheart and tell her that she has no objection to marrying someone other than me… If I ask you, my sweetheart, tell her that this person whom we are talking about, he has rested. -

Eugenetica in Italia.Pdf

Nuova Cultura 119 Francesco Cassata Molti, sani e forti L’eugenetica in Italia Bollati Boringhieri Prima edizione gennaio 2006 © 2006 Bollati Boringhieri editore s.r.l., Torino, corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 86 I diritti di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento tota- le o parziale con qualsiasi mezzo (compresi i microfilm e le copie fotostatiche) sono riservati Stampato in Italia dalla Litografia «Il Mettifoglio» di Torino isbn 88-339-1644-8 Schema grafico della copertina di Pierluigi Cerri Indice 9 Introduzione Molti, sani e forti 27 1. Londra 1912: l’Italia scopre l’eugenica 1. L’antropologia di Giuseppe Sergi, 28 2. Razza e psiche: eugenica e psi- chiatria in Enrico Morselli, 35 3. Eugenica e sociobiologia: il problema delle élite, 41 4. Il Comitato Italiano per gli Studi di Eugenica (1913), 49 52 2. Eugenica di guerra 1. La guerra e l’«eugenica a rovescio», 52 2. La guerra come «palestra», 62 3. La guerra come «laboratorio», 65 4. Un «caso» di eugenica: i «figli del nemico», 71 76 3. L’eugenica all’ordine del giorno (1919-1924) 1. Ettore Levi e la proposta del birth control, 83 2. Una proposta con- creta: il certificato prematrimoniale, 98 3. Il volto duro dell’eugenica: sterilizzazione ed eutanasia, 114 4. Il lavoro degli «inutili»: l’igiene mentale in Italia, 125 141 4. Eugenica e fascismo 1. L’eugenica «rinnovatrice» di Corrado Gini, 144 2. Il totalitarismo biologico di Nicola Pende, 188 3. Un tentativo di sintesi: Marcello Bol- drini e la «demografia costituzionalistica», 211 220 5. Eugenica e razzismo 1. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

The Jewish Discovery of Islam

The Jewish Discovery of Islam The Jewish Discovery of Islam S tudies in H onor of B er nar d Lewis edited by Martin Kramer The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University T el A v iv First published in 1999 in Israel by The Moshe Dayan Cotter for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University Tel Aviv 69978, Israel [email protected] www.dayan.org Copyright O 1999 by Tel Aviv University ISBN 965-224-040-0 (hardback) ISBN 965-224-038-9 (paperback) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Publication of this book has been made possible by a grant from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation. Cover illustration: The Great Synagogue (const. 1854-59), Dohány Street, Budapest, Hungary, photograph by the late Gábor Hegyi, 1982. Beth Hatefiitsoth, Tel Aviv, courtesy of the Hegyi family. Cover design: Ruth Beth-Or Production: Elena Lesnick Printed in Israel on acid-free paper by A.R.T. Offset Services Ltd., Tel Aviv Contents Preface vii Introduction, Martin Kramer 1 1. Pedigree Remembered, Reconstructed, Invented: Benjamin Disraeli between East and West, Minna Rozen 49 2. ‘Jew’ and Jesuit at the Origins of Arabism: William Gifford Palgrave, Benjamin Braude 77 3. Arminius Vámbéry: Identities in Conflict, Jacob M. Landau 95 4. Abraham Geiger: A Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reformer on the Origins of Islam, Jacob Lassner 103 5. Ignaz Goldziher on Ernest Renan: From Orientalist Philology to the Study of Islam, Lawrence I. -

Repression of Homosexuals Under Italian Fascism

ªSore on the nation©s bodyº: Repression of homosexuals under Italian Fascism by Eszter Andits Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Constantin Iordachi Second Reader: Professor Miklós Lojkó CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may be not made with the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract This thesis is written about Italian Fascism and its repression of homosexuality, drawing on primary sources of Italian legislation, archival data, and on the few existent (and in most of the cases fragmentary) secondary literatures on this puzzling and relatively under- represented topic. Despite the absence of proper criminal laws against homosexuality, the Fascist regime provided its authorities with the powers to realize their prejudices against homosexuals in action, which resulted in sending more hundreds of ªpederastsº to political or common confinement. Homosexuality which, during the Ventennio shifted from being ªonlyº immoral to being a real danger to the grandness of the race, was incompatible with the totalitarian Fascist plans of executing an ªanthropological revolutionºof the Italian population. Even if the homosexual repression grew simultaneously with the growing Italian sympathy towards Nazi Germany, this increased intolerance can not attributed only to the German influence. -

Pottery from Roman Malta

Cover Much of what is known about Malta’s ancient material culture has come to light as a result of antiquarian research or early archaeological work – a time where little attention Anastasi MALTA ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIEW SUPPLEMENT 1 was paid to stratigraphic context. This situation has in part contributed to the problem of reliably sourcing and dating Maltese Roman-period pottery, particularly locally produced forms common on nearly all ancient Maltese sites. Pottery from Roman Malta presents a comprehensive study of Maltese pottery forms from key stratified deposits spanning the first century BC to mid-fourth century AD. Ceramic material from three Maltese sites was analysed and quantified in a bid to understand Maltese pottery production during the Roman period, and trace the type and volume of ceramic-borne goods that were circulating the central Mediterranean during the period. A short review of the islands’ recent literature on Roman pottery is discussed, followed by a detailed Pottery from Roman Malta contextual summary of the archaeological contexts presented in this study. The work is supplemented by a detailed illustrated catalogue of all the forms identified within the assemblages, presenting the wide range of locally produced and imported pottery types typical of the Maltese Roman period. Maxine Anastasi is a Lecturer at the Department of Classics and Archaeology, University of Malta. She was awarded a DPhil in Archaeology from the University of Oxford for her dissertation on small-island economies in the Central Mediterranean. Her research primarily focuses on Roman pottery in the central Mediterranean, with a particular Malta from Roman Pottery emphasis on Maltese assemblages. -

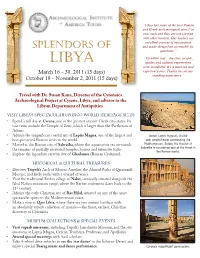

Splendors of and Made Themselves Accessible for Questions.”

“Libya has some of the best Roman and Greek archaeological sites I’ve ever seen and they are not overrun with other tourists. Our leaders are excellent sources of information SplendorS of and made themselves accessible for questions.” “Excellent tour—the sites, people, libya guides and cultural experiences were wonderful. It’s a must see and March 16 – 30, 2011 (15 days) experience tour. Thanks for an out- October 19 – November 2, 2011 (15 days) standing experience.” Travel with Dr. Susan Kane, Director of the Cyrenaica Archaeological Project at Cyrene, Libya, and advisor to the Libyan Department of Antiquities. VISIT LIBYA’S SPECTACULAR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES: • Spend a full day at Cyrene, one of the greatest ancient Greek city-states. Its vast ruins include the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon of Athens. • Admire the magnificent coastal site of Leptis Magna, one of the largest and Above, Leptis Magna’s 16,000 seat amphitheater overlooking the best-preserved Roman cities in the world. Mediterranean. Below, the theater at • Marvel at the Roman city of Sabratha, where the aquamarine sea surrounds Sabratha is considered one of the finest in the remains of partially excavated temples, houses and extensive baths. the Roman world. • Explore the legendary caravan city of Ghadames (Roman Cydamus). HISTORICAL & CULTURAL TREASURES • Discover Tripoli’s Arch of Marcus Aurelius, the Ahmad Pasha al Qaramanli Mosque, and lively souks with a myriad of wares. • Visit the traditional Berber village of Nalut, scenically situated alongside the Jabal Nafusa mountain range, where the Berber settlement dates back to the 11th century. -

Scarica Il Programma Definitivo

virtuale CONGRESSO NAZIONALE 655°SIGG NessunoNessuno EsclusoEscluso Dall’acuzieDall’acuzie allaalla cronicità,cronicità, allealle malattiemalattie rarerare cheche invecchianoinvecchiano 2-4 dicembre 2020 PROGRAMMA DEFINITIVO CONGRESSO NAZIONALE ORGANI ASSOCIATIVI SIGG CONSIGLIO DIRETTIVO COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI DEI CONTI Piemonte/Valle d’Aosta Vittoria Tibaldi (Torino) Presidente Raffaele Antonelli Incalzi (Roma) Vincenzo Canonico (Napoli) Puglia/Basilicata Vincenzo Solfrizzi (Bari) Past President Nicola Ferrara (Napoli) Giovambattista Desideri (L’Aquila) Sardegna Diego Costaggiu (Olbia) Presidente Eletto Francesco Landi (Roma) Marco Trabucchi (Brescia) Sicilia Ferdinando D’Amico (Patti) Segretario Mario Barbagallo (Palermo) Toscana Fabio Monzani (Pisa) Tesoriere Daniela Mari (Milano) COLLEGIO DEI PROBIVIRI Umbria In fase di nomina Giulio Masotti (Firenze) Veneto/Trentino Alto Adige Giuseppe Sergi (Padova) Settore Scientifico Disciplinare Clinico Patrizio Odetti (Genova) Coordinatore - Stefano Volpato (Ferrara) Franco Rengo (Napoli) COORDINATORI DELLE SEZIONI REGIONALI Coordinatore Vicario - Antonio Greco (S. Giovanni Rotondo) Area Nord Giovanni Ricevuti (Pavia) Donatella Calvani (Prato) PRESIDENTI ONORARI Area Centro e Sardegna Chiara Mussi (Modena) Andrea Corsonello (Cosenza) Gaetano Crepaldi (Padova) Area Sud e Sicilia Alba Malara (Lamezia Terme) Giovanni Carlo Isaia (Torino) Giulio Masotti (Firenze) Stefania Maggi (Padova) Mario Passeri (Parma) COMITATO SCIENTIFICO 65° CONGRESSO NAZIONALE Raffaele Marfella (Napoli) Franco Rengo (Napoli)