Niobe Repeating: Black New Women Rewrite Ovid's Metamorphoses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camora 1.Pdf

The Function of the Rhetoric of Maternity in the Representation of Female Sexuality, Religion, Nationality, and Race in Early Modern English Literature and Culture by Cecilia Morales A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Schoenfeldt, Chair Dr. Neeraja Aravamudan, Edward Ginsberg Center, University of Michigan Professor Peggy McCracken Professor Catherine Sanok Professor Valerie Traub Cecilia Morales [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7428-3777 © Cecilia Morales 2020 Acknowledgements Throughout my doctoral studies, I have been fortunate to have the love and support of countless individuals, to whom I owe a great deal of gratitude. I’d like to begin by thanking my committee members. Cathy and Peggy taught me valuable lessons not only about my work but about being a thoughtful and compassionate scholar and teacher. Valerie’s reminders to always be as generous as possible when discussing the work of other scholars has kept me sane and stable in this competitive world of academia. Mike helped me, a displaced Texan, to feel at home in Michigan from our first meeting, during which we chatted about both Shakespearean scholarship and Tex Mex. Finally, the most recent addition to my committee is Neeraja Aravamudan, who I consider my most active mentor and supporter. One of the best decisions I made during graduate school was accepting an internship at the Edward Ginsberg Center, where Neeraja became my supervisor. Neeraja and the other Ginsberg staff remind me it’s possible to take my work very seriously without taking myself too seriously. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

June 2002 Newsletter

American Philological Association NEWSLETTER JUNE 2002 Volume 25, Number 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Message from the President. .1 Recently you all received a copy of the APA’s splendid TLL Fellowship Announcement for 2003-04 . .2 new publication, Amphora. Edited by Margaret Brucia Lionel Pearson Fellowship Announcement for and Anne-Marie Lewis, this is the latest undertaking by 2003-2004. 3 our new Outreach Division. It is intended for a wide Call for Roundtable Proposals. .3 audience of teachers, students and others interested in Classics. I urge you to read it, bring it to the attention of Recent APA Publications. .3 anyone you think might be interested (we are willing to Awards to Members. .4 send out additional copies, within reason), and also con- University and College Appointments. 5 sider submitting material to it. Dissertation Listings. .7 Of course, “outreach” is something virtually all of us Election Ballot and Materials. Pink Insert have been doing as long as we have been in Classics, Announcements. .16 perhaps without thinking of it as such. Like other APA members, I have done many things that might be con- Calls for Abstracts / Meetings. .16 sidered outreach, from telling Greek myths to 2nd grad- Funding Opportunities / Fellowships . 18 ers to talking to the local DAR chapter about Athenian law and democracy. In fact, I find that discussing our Reminder for Organizers of Panels at 2004 field with those outside it, whether in a formal presenta- APA Annual Meeting. 20 tion, at a party, or just talking to a seatmate on the plane, Greek Keys 2002 Order Form. -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

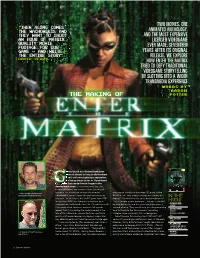

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

William L. W Estermann Entre O Antiquarianismo E A

WILLIAM L. WESTERMANN ENTRE O ANTIQUARIANISMO E A HISTÓRIA COMPARADA DA ESCRAVIDÃO: UMA RELEITURA DE THE SLAVE SYSTEMS OF GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITY Fábio Duarte Joly1 RESUMO: O livro de William L. Westermann, The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity, publicado em 1955, é até hoje uma referência para o estudo da escravidão antiga. No entanto, este livro é frequentemente criticado por sua estrutura antiquária e, portanto, pela falta de qualquer abordagem teórica sobre a escravidão no mundo antigo. Esse ponto de vista foi enfatizado principalmente por Moses Finley, com sua obra Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology (1980), e tornou-se, desde então, um certo consenso na historiografia da escravidão. Este artigo argumenta que tal abordagem negligencia o lugar do livro de Westermann nos debates sobre a história comparada da escravidão que ocorreram nos Estados Unidos durante a segunda metade do século XX. Existem semelhanças entre a tese de Frank Tannenbaum sobre os diferentes níveis de severidade nos sistemas escravistas nas Américas, apresentados em seu Slave and Citizen (1946), e a visão de Westermann acerca dos antigos sistemas escravistas. Essa semelhança é compreensível se levarmos em conta que ambos participaram de seminários sobre a história do trabalho e da escravidão na Universidade de Columbia. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Escravidão Antiga; História Comparada; William L. Westermann; Frank Tannenbaum. ABSTRACT: William L. Westermann’s The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity, published in 1955, is until today a reference guide to the study of ancient slavery. However, this book is often criticized for its antiquarian structure and, therefore, for a lack of any theoretical approach to slavery in the ancient world. -

State Proposes All-Out War on Narcotics Racket

OHIO'STATE miSEUH, LIBRARY 15TH * HIQH 3T. 15*1 JBLWL] ISThre e Checks For The .NAACP COLUVBUS, OHIO VOL. 6, No. 37 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 19, 1958 COLUMBUS. OHIO Name Bell, Ex-Star Athlete, Carter Band To Play For »5_te_t__" I P«opl«*s I To Commission's Legal Staff IChampionl BY JOHN B. COMBS Legion Event Napoleon Bell of Youngstown Jimmy Carter and his bond Roy Wilkins. administrator, NAACP, third from left, ao ' gave up a promising career as will provide music for the cab- cepts checks from W. W. Wachtel, president of Calvert Distill, SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 19SS COLUMBUS, OHIO a professional football player party being presented by ers, third from right, and from Men of Distinction Earthman five years ago to study law at Fort, insurance executive (left), and" Dr. Austin Curtis, former Western Reserve university at assistant to George Washington Carver, fourth from -left. Look Cleveland. ing on are Men of Distinction Lyman Burrls, tax expert; Charles Two weeks ago, he received hall. Local 927, 2741 £ Sth av. A W. Jones, lawyer, and Edward Davis, automobile dealer, hia first large dividend from his floor-show ij also included in the law studies when he because a member of the legal staff of the State Industrial Commission. Buckeye Boy's State this : Salisbury To Tell Of The 27 year old attorney was mer. Last summer, two Colum a onetime football star at Mt. bus youths were sponsored by Union college at Alliance. Upon this post along with Mt Vernon graduating from there, he had a Av. Businessmen's Ass'n and Iron Curtain Life On TM choice of joining the Los Ange The Ohio Sentinel. -

Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States

PUBLIC PAPERS OF THE PRESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES i VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 ii VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 iii VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 iv VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 Foreword During the second half of 1994, America continued to move forward to help strengthen the American Dream of prosperity here at home and help spread peace and democracy around the world. The American people saw the rewards that grew out of our efforts in the first 18 months of my Administration. Economic growth increased in strength, and the number of new jobs created during my Administration rose to 4.7 million. After 6 years of delay, the American people had a Crime Bill, which will put 100,000 police officers on our streets and take 19 deadly assault weapons off the street. We saw our National Service initiative become a reality as I swore in the first 20,000 AmeriCorps members, giving them the opportunity to serve their country and to earn money for their education. -

Theban Walls in Homeric Epic Corinne Ondine Pache Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department 10-2014 Theban Walls in Homeric Epic Corinne Ondine Pache Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation Pache, C. (2014). Theban walls in Homeric epic. Trends in Classics, 6(2), 278-296. doi:10.1515/tc-2014-0015 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TC 2014; 6(2): 278–296 Corinne Pache Theban Walls in Homeric Epic DOI 10.1515/tc-2014-0015 Throughout the Iliad, the Greeks at Troy often refer to the wars at Thebes in their speeches, and several important warriors fighting on the Greek side at Troy also fought at Thebes and are related to Theban heroes who besieged the Boeotian city a generation earlier. The Theban wars thus stand in the shadow of the story of war at Troy, another city surrounded by walls supposed to be impregnable. In the Odyssey, the Theban connections are less central, but nevertheless significant as one of our few sources concerning the building of the Theban walls. In this essay, I analyze Theban traces in Homeric epic as they relate to city walls. Since nothing explicitly concerning walls remains in the extant fragments of the Theban Cycle, we must look to Homeric poetry for formulaic and thematic elements that can be connected with Theban epic. -

Something Akin to Freedom

ሃሁሂ INTRODUCTION I can see that my choices were never truly mine alone—and that that is how it should be, that to assert otherwise is to chase after a sorry sort of freedom. —Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance n an early passage in Toni Morrison’s second novel, Sula (1973), Nel Iand Sula, two young black girls, are accosted by four Irish boys. This confrontation follows weeks in which the girls alter their route home in order to avoid the threatening boys. Although the boys once caught Nel and “pushed her from hand to hand,” they eventually “grew tired of her helpless face” (54) and let her go. Nel’s release only amplifies the boys’ power as she becomes a victim awaiting future attack. Nel and Sula must be ever vigilant as they change their routines to avoid a confrontation. For the boys, Nel and Sula are playthings, but for the girls, the threat posed by a chance encounter restructures their lives. All power is held by the white boys; all fear lies with the vulnerable girls. But one day Sula declares that they should “go on home the short- est way,” and the boys, “[s]potting their prey,” move in to attack. The boys are twice their number, stronger, faster, and white. They smile as they approach; this will not be a fi ght, but a rout—that is, until Sula changes everything: Sula squatted down in the dirt road and put everything down on the ground: her lunch pail, her reader, her mittens, and her slate. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds.